Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMUSIC

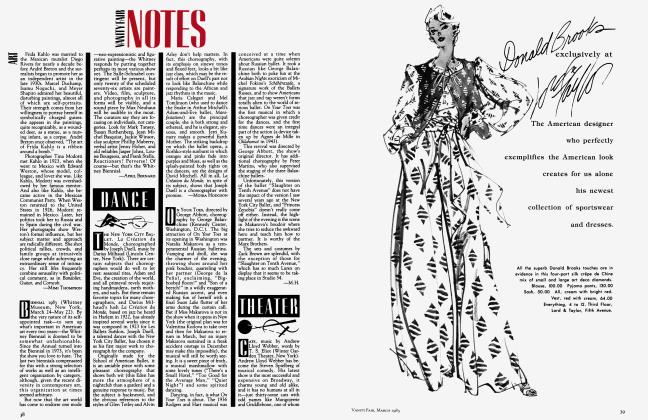

THE PHOTOGRAPHER, by Philip Glass (CBS). CBS puts Glass on what it calls its crossover label, along with Placido Domingo singing Beatles songs. Is Glass classical or is he pop? He’d say he’s classical, and shouldn’t be blamed if his rhythms appeal to a crowd that usually likes rock. More and more he strikes me as our foremost composer of—believe it or not—sacred music.

Two years ago, in his opera Satyagraha, Glass showed us how that’s so. His characteristic musical stasis mirrored the changeless compassion of the Hindu gods invoked by Gandhi (the main character) in the opening scene. In an earlier piece he had used woodwinds’ dizzy spirals to convey the exuberance of spinning dancers, but in Satyagraha they evoke ethereal fifes skirling for an army of spiritual pilgrims (Gandhi’s, in this case; but for a Buddhist like Glass we’re all moving down the same holy road).

In The Photographer, excerpted on this recording, he seems to have written music about the spiritual joy of art and everyday life. The work is a theater piece, part play, part dance, part concert, written for the Holland Festival and first performed there last year; it’s about the nineteenth-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge, best known for sequential stills that freeze the movement of running men and trotting horses. The stills don’t move, but Muybridge creates a sense of movement between them: the viewer sees a horse’s hoof angled, then straightened, a man’s leg flexed, then stretched. Glass develops his music the same way, more so in this piece than ever before. There has always been repetition in his music, but each time he repeats a fragment here, it seems to grow in all directions at once.

His wordless choirs have always sounded as if they’d wandered in from the background score of a movie about space or the Grand Canyon; in Act 1 of The Photographer, in the middle of a song with lyrics by the Talking Heads’ David Byrne, the chorus bursts for a giddy moment into everyday speech. The “concert” music of Act 2 is spiced with blues. Most exuberant of all is the Act 3 dance, which swells five times from a handful of notes into a torrent that grows steadily louder and more overwhelmingly joyful. Glass’s spiritual journey here sounds like a trip through a rock club or a crowded street.

GREGORY SANDOW

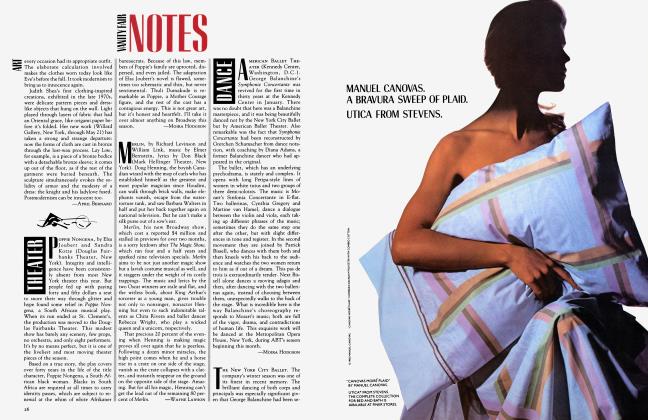

MAHLER: Symphony No. 9, the Chicago Symphony conducted by Sir George Solti (London), It’s a question whether the final song of Das Lied von der Erde or the Adagio that ends his Ninth Symphony is the most moving music Mahler wrote. Both are lingering farewells by a man who had been told he hadn’t long to live and who indeed died without hearing his last completed symphony performed. But in its middle movements the Mahler Ninth is also a work of withering sarcasm and ferocious anger by a man unwilling to make nice about dying. The resolution of this extreme range of feelings, from tender regret to rage, is what makes the concluding Adagio so powerful.

Solti’s 1967 recording has enjoyed a higher reputation than it deserves. His new one is distinctly better: the bucolic opening is allowed to breathe and sing in a more relaxed way, the cloddish country-dance second movement has a sardonic swing, the third rises to a semblance of fury, and the Adagio is warmer than before. Yet I nowhere hear enough emotional commitment or openness of feeling. Solti’s Mahler is clear, tight, and rather hard. The Mahler Ninth with which all subsequent readings must face comparison is Jascha Horenstein’s Vox mono of the 1950s, later “electronically reprocessed to simulate stereo” (tolerably) by Turnabout. It should never be out of the catalogue, as it now is. Horenstein combined patrician control with passionate intensity in a way I haven’t heard equaled.

WALTER CLEMONS

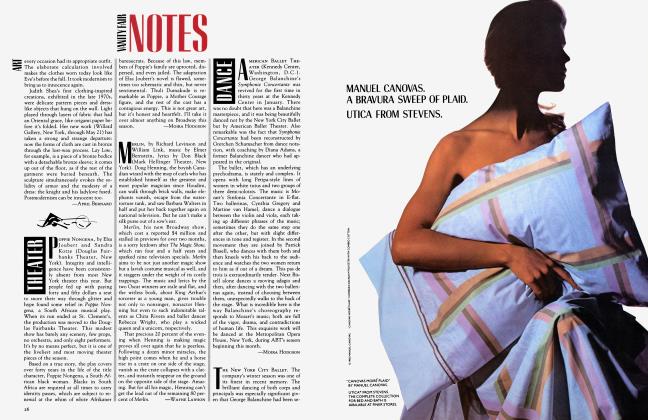

WHAMMY!, the B-52’s (Warner Bros.).

SHE: Wanna be...Empress of Fashion.

HE: Wannabe. . .President of Moscow. CHORUS: Let's meet and have a baby now!

When they’re hot, the B-52’s could make the ghost of Jefferson Davis get up and do the hokey-pokey. Hailing from the paneled dens and poolside barbecues of Athens, Georgia, they make music the way Roger Corman makes movies: fast, fun, and with just a suspicion of subversive intelligence. The world according to the B-52’s is a place where “party is a verb, rhythm is a given, and driveins are a way of life.

On Whammy!—a full-length album, following their David Byrneproduced mini-LP Mesopotamia—the B-52’s go on a spree through the supermarket of modern culture, borrowing bongos from the Mission: Impossible theme, guitar leads from the Ventures, and literary inspiration from Andre Gide. From “Legal Tender” (a juiced-up rocker about the pleasures of counterfeiting) to “Butter Bean” (a paean to vegetable love), the album’s first side is sweeter than Nehi Grape, more fun than daytime TV.

The only dull moments are on the album’s second side: “Don’t Worry,” an edgy exhortation that would make any normal person more nervous, and “Baked Alaska,” a big, empty instrumental. For the most part, though, there is music to move the average feet.

Cindy Wilson’s voice carries the tunes with room to spare for wit, wistfulness, and enough “aw shucks” sexuality to make a boy blush. The rest of the group, especially drummer Keith Strickland, can really rock when they want to. If the B-52’s get any better, we’re going to have to bring back bouffants and beach blanket bingo.

D. D. GUTTENPLAN

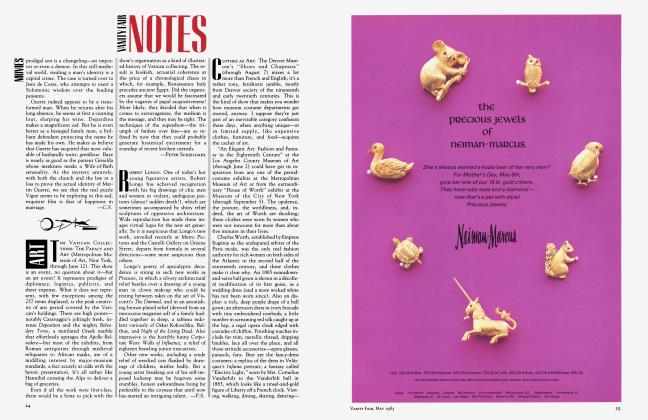

SYNCHRONICITY, the Police (A&M). The Police have often been accused of exploiting the exotic while depending on the familiar: their idiosyncratic mix of reggae and rock (not to mention jazz and soul) got them noticed, and a few well-placed pop hooks (not to mention bleachedblond good looks) put them on the charts. Yet their aim has always been true. In seeking out missing musical links and cross-cultural connections, singer-bassist Sting, guitarist Andy Summers, and drummer Stewart Copeland have defied the limitations of the typical rock trio. With each new album they’ve carved a little more common ground out of the woefully fragmented world of pop music. They’ve attracted an audience as wide-ranging as their influence. And, on Synchronicity, their fifth and best, the Police want to tell us what all this means.

To wit: common ground must imply a common purpose, a notion songwriter Sting has been mulling over earnestly since 1981’s Ghost in the Machine, in which he declared, “There is no political solution for our troubled evolution.” Sting, whose voice can be teasingly malevolent or vulnerably candid, is a better reporter than philosopher, though; he’s always had a knack with the odd detail—he once rhymed Nabokov with shake and cough—and he’s at his most vivid and entertaining when he turns mysterious or whimsical. He envisions a Loch Ness-like monster rising up out of its dark Scottish lake as a symbol of all unseen possibilities in a dreary world, and he speaks to the ghosts of dinosaurs, wondering if we’re walking in their footsteps.

Synchronicity is thoroughly persuasive because the Police never overstate their case, thematically or musically. Guitarist Summers weaves ethereal textures; drummer Copeland employs the pause as judiciously as the wallop; and bassist Sting turns his instrument into a breath, imperceptible or obvious, always marking time. For those who don’t want their apocalypse now, the Police include “Every Breath You Take,” a lush, hit-bound love song with a touch so subtle and sure that no statement of purpose is necessary.

MICHAEL HILL

A CHILDS ADVENTURE, Marianne Faithfull (Island). In mid-’60s England, Marianne Faithfull was the sad girl of rock ’n’ roll, the tomboy with the propitiatory candy bar, lost at the party. Amid the callow revelry, bravado, and peacockery of the time, hers was the singular soft voice of melancholy.

It has been nearly twenty years since “As Tears Go By” was released, in 1964. Its singer is still sad, but not in the privileged, romantic fashion of her candy bar days. Of the eight songs on A Childs Adventure, only two are not of a decidedly darkvapored mood; and those two—a bored-chic disco caprice called “The Blue Millionaire” and “Ireland,” a piece of Hibernian twaddle confected so utterly of cliches that one almost expects Paddy to come gamboling through the aural clover with a whittled cake of Irish Spring and a cry of “Aye, and manly too!”—seem to have been fashioned with an eye toward the till. The remaining six songs, the dark blue ones, are more striking and well made than anything on her last album, Dangerous Acquaintances, or on her 1979 Broken English, where even the good material was ruined by too much synthesizer silliness.

Much of what Marianne Faithfull is singing about here has to do with her own entwined weaknesses, fear and booze. When her songs lapse into dreaminess or, more often, into nightmarishness, she is running or falling, or both, as in “Falling from Grace,” the song that is most evocative, lyrically and musically, of the scary, through-the-looking-glass enchantment of the album’s title. “Times Square” and “She’s Got a Problem” are grim ponderings on alcoholic dissolution, distinctly suicidal about the edges, but unmarred by self-pity, and seductively lovely to hear.

The opening song on the second side, “Ashes in My Hand,” is the album’s most despairing; the only hopeful moment, “Morning Come,” is also the truest. Although she perceives herself as weak, it is her strength, immanent in the somber grace and force of the songs and of the voice that sings them, that gives Marianne Faithfull’s gloom its heroic quality. Some beasts prevail in the dark, and she is one of them.

NICK TOSCHES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now