Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPARSIFAL

Walter Clemons

The View from Wagner's Head

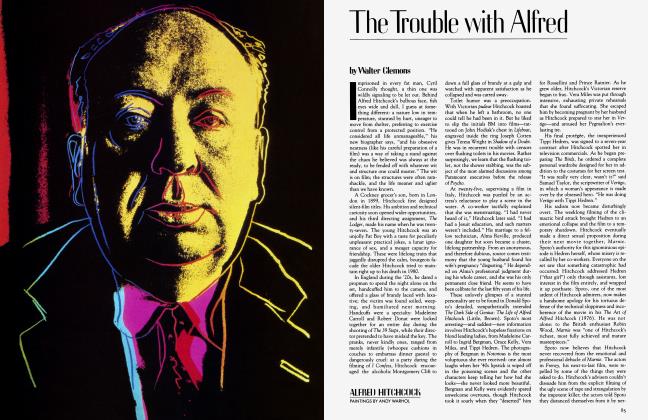

Hans-Jurgen Syberberg has made something eerily original: neither an easily fluent "movie" realization of Richard Wagner's Parsifal nor a photographed performance of the opera. Instead, he has given us a work that is both performance and commentary, crammed with startling references. Syberberg has explained that he conceived the entire film as taking place around and inside a fifty-foot concrete replica of Wagner's death mask. We're dealing with something more than a design conceit here, a "concept" imposed on a production. Syberberg drastically sets out to rethink and reargue— even to compete with—Wagner's final creation; in entering Wagner's gigantic head, he attempts to become him, while bringing his own edgy late-twentieth-century sensibility along. His Parsifal is probably the most disturbing and exciting opera film ever made.

The mysterious opening is a signal of what we're in for. While the conductor murmurs instructions and the orchestra rehearses broken fragments of the opera, we look at splattered postcards that might have been mailed from some End-of-Civilization-As-We-Know-It post office: ruined cloisters, monuments bombed out of existence in Dresden in 1945, a cracked freeway, a toppled Statue of Liberty vainly lifting its arm out of black water.

Once the long, slow, ethereal Prelude begins, Syberberg pulls off the first of many striking successes, a truly cinematic solution to the problem of "what to do" during a purely orchestral passage. After prolonged research into the tangled Percival legend, Wagner began his opera in medias res, with the boy's arrival and initial rejection at the court of the Grail. While the Prelude unfolds, Syberberg provides us with the whole background, performed by grotesquely elegant puppet figures: Parsifal's heritage and boyhood, the wounding of Amfortas and the passing of the holy spear to Klingsor. During the course of the opera all these matters will he explained in long narrative monologues. Syberberg's enigmatic puppet theater fixes them in our imagination from the start.

When the opera begins, it soon becomes apparent that Syberberg's Parsifal is a cinematic anomaly, with long, six-toeight-minute takes and a Spartan refusal to take filmic advantage of Wagnerian "magic" that usually fails onstage. "It is a point of honor not to laugh in the Wagner Theater," Shaw wrote from Bayreuth in 1889, "where the chances offered to ribalds are innumerable: take as instances the solemn death and funeral of the stuffed swan...and the vagaries of the sacred spear, which either refuses to fly at Parsifal at all or else wraps its fixings round his ankles like an unnaturally thin hoa constrictor." Here, the swan is a model of the porcelain one in Ludwig of Bavaria's collection, and Klingsor falls over without even hurling the spear.

The movie is great fun as a Kultur quiz. We see plaster heads of Wagner, Nietzsche, and Marx propped at the base of a huge phallus. Magnified hack projections of details from paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and Caspar David Friedrich loom up. The first-act transformation scene, in which Gurnemanz leads Parsifal to the Grail castle, is like a tour of Charles Foster Kane's warehouse: rocks divide to reveal a nineteenth-century backdrop of a sky-flying Valkyrie; the two stroll down a corridor hung with knightly banners, a Nazi flag conspicuous among them.

A stairway mounted through the enormous quilted lapels of one of Wagner's famous dressing gowns is a visual stunner. But not everything works. The terraced Good Friday scene, with greenhouse ceiling and nursery flats of spring flowers, is an eyesore. Having done my homework, I know the dinky fountain is a visual quotation from Van Eyck's Ghent altarpiece, the A dotation of the Lamb, but that didn't help me during the movie. When we pause too long over the quiz, or flunk it, we are distracted from the drama.

(continued on page 108)

(continued from page 105)

Luckily the film has a blazing dramatic center—the German actress Edith Clever's performance as Kundry (sung by Yvonne Minton), one of the most impossible roles in opera. She comes on covered with mud, mysterious in origin and loyalty, a servitor of the Grail knights who is in fact in thrall to their enemy, the magician Klingsor. She must play bone-weary depression, maternal longing, dazzling sexual aggression, fanatical religious conversion, and eventual spiritual transfiguration. Edith Clever is a strong-bodied, magnetically beautiful woman who looks at various moments like Colleen Dewhurst, Glenda Jackson (in fury), and Ursula Andress. Her dramatic energy makes this one of the great movie performances, instantly identifiable as one to be reseen and talked about for years.

At Parsifal's first entrance we see something never possible in an opera house: Parsifal as a frail, unformed, utterly simple boy. The actor, Michael Kutter, is a Swiss apprentice filmmaker who was shooting his first documentary when Syberberg discovered him. As we listen to the Wagnerian tenor (Reiner Goldberg's) that emerges from his bony, openly expressive teenager's face, Parsifal's halting replies to Gurnemanz's questions become deeply moving. His ignorance of his parentage and his name, his "Who is good?"—his purity—have never been so convincing. When Kundry spitefully tells him his mother has died during his wandering, he moves to strangle her, and Edith Clever converts the moment into an embrace both maternal and sexual. This is an electrifying preparation for the seduction scene in Act 2, in which Kundry exposes her breast to the boy, an act that is an exposure both to adult knowledge and to tabooed desire for the mother. This crucial, complex scene can never have been so tellingly acted.

After Parsifal resists Kundry, Syberberg changes actors. Parsifal is thenceforth performed by a young woman, Karin Krick, of Joan of Arc demeanor and with the face of a Memling Virgin. I see the intention: when Parsifal loses his boyish innocence in the encounter with Kundry, he becomes an androgynous pilgrim. But the change of sex is irreparably distracting. I rather expected Parsifal to return as a man at the beginning of Act 3. But that isn't Syberberg's choice; his two Parsifals are touchingly reintegrated in the film's final moments. He has made other interesting choices. Robert Lloyd, who plays and sings Gurnemanz, is young and handsome, a refreshing change from the customary assignment of the role to Wagnerian veterans on their last legs. But his unchanged appearance in Act 3, like the re-entrance of Karin Krick, sacrifices a vital element in the story—the sense of many years having passed before the return of an older Parsifal to a ruined Grail court.

The last act of Parsifal is always a chore. Syberberg holds our attention with his steady, unembarrassed filming of ceremonial kitsch—anointing, feet washing and hair wiping, procession, and apotheosis. Though the material is fearlessly faced, I confess to looking at my watch. But Syberberg ends with an assertion of his own skeptical sensibility: a crowned skull, with dry-ice fog drifting round it, and a full-face close-up of Kundry, whom we have just seen laid out in sanctity. She reappears, hair tangled and gaze savage, as we first met her. The last sounds we hear, as the end credits roll, are her unregenerate, guttural groans, with which the film began.

The four-and-a-quarter-hour film, refused government backing and the cooperation of Bayreuth, was planned for three years, then shot in thirty-five days (Syberberg's seven-hour Hitler, a Film from Germany, after four years' planning, was shot in twenty days in Munich). In oddity, intellectual reach, and emotional power, Parsifal is unique among opera films. Ingmar Bergman's The Magic Flute, Joseph Losey's Don Giovanni, and Jean-Pierre Ponnelle's television films of the three surviving Monteverdi operas aren't comparable in ambition and dizzying risk.

Syberberg's book Parsifal: Notes on a Film, published in Munich and Paris, arrived only after I'd seen his movie twice. In it, Syberberg explains his intentions in pedantic detail. At the close of Act 1, we see Parsifal standing dejected before the huge replica of Wagner's death mask. Kundry and Klingsor climb it in Act 2, and it splits open in the last scene to permit entry into the sanctuary of the Grail. But I doubt that even the most attentive viewer could be expected to guess, without having read Syberberg's explanation, that when Gurnemanz leads Parsifal through a rocky defile in Act 1, the two are traveling inside the composer's head "north to south, from forehead to lips." I now understand better the hypnotic quality of the film. We respond to an excessive, concealed control even when we don't fully recognize what's being done to us. For the better part of four and a quarter hours, Syberberg's reinvention of Wagner's music drama holds us in hushed alertness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now