Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Trouble with Alfred

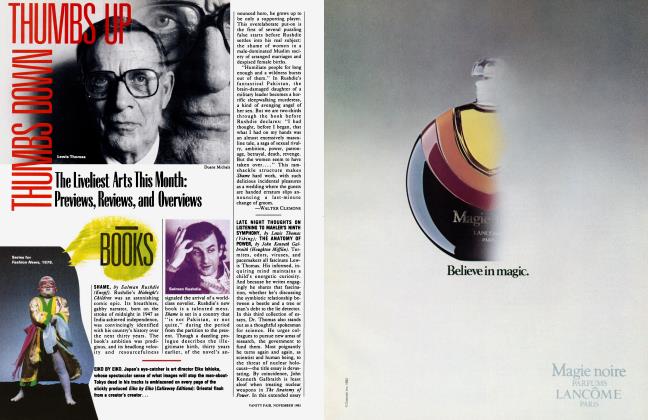

Walter Clemons

Imprisoned in every fat man, Cyril Connolly thought, a thin one was wildly signaling to be let out. Behind Alfred Hitchcock's bulbous face, fish eyes wide and dull, I guess at something different: a nature low in temperature, stunned by hurt, uneager to move from shelter, preferring to exercise control from a protected position. "He considered all life unmanageable," his new biographer says, "and his obsessive neatness (like his careful preparation of a film) was a way of taking a stand against the chaos he believed was always at the ready, to be fended off with whatever wit and structure one could muster." The wit is on film; the structures were often ramshackle, and the life meaner and uglier than we have known.

A Cockney grocer's son, bom in London in 1899, Hitchcock first designed silent-film titles. His ambition and technical curiosity soon opened wider opportunities, and his third directing assignment, The Lodger, made his name when he was twenty-seven. The young Hitchcock was an unjolly Fat Boy with a taste for peculiarly unpleasant practical jokes, a lunar ignorance of sex, and a meager capacity for friendship. These were lifelong traits that jaggedly disrupted the calm, bourgeois facade the older Hitchcock tried to maintain right up to his death in 1980.

In England during the '20s, he dared a propman to spend the night alone on the set, handcuffed him to the camera, and offered a glass of brandy laced with laxative; the victim was found soiled, weeping, and humiliated next morning. Handcuffs were a specialty: Madeleine Carroll and Robert Donat were locked together for an entire day during the shooting of The 39 Steps, while their director pretended to have mislaid the key. The pranks, never kindly ones, ranged from merely infantile (whoopee cushions in couches to embarrass dinner guests) to dangerously cruel: at a party during the filming of I Confess, Hitchcock encouraged the alcoholic Montgomery Clift to down a full glass of brandy at a gulp and watched with apparent satisfaction as he collapsed and was carted away.

Toilet humor was a preoccupation. With Victorian pudeur Hitchcock boasted that when he left a bathroom, no one could tell he had been in it. But he liked to slip the initials BM into films—tattooed on John Hodiak's chest in Lifeboat, engraved inside the ring Joseph Cotten gives Teresa Wright in Shadow of a Doubt. He was in recurrent trouble with censors over flushing toilets in his movies. Rather surprisingly, we learn that the flushing toilet, not the shower stabbing, was the subject of the most alarmed discussions among Paramount executives before the release of Psycho.

At twenty-five, supervising a film in Italy, Hitchcock was puzzled by an actress's reluctance to play a scene in the water. A co-worker tactfully explained that she was menstruating. "I had never heard of it," Hitchcock later said. "I had had a Jesuit education, and such matters weren't included." His marriage to a fellow technician, Alma Reville, produced one daughter but soon became a chaste, lifelong partnership. From an anonymous, and therefore dubious, source comes testimony that the young husband found his wife's pregnancy "disgusting." He depended on Alma's professional judgment during his whole career, and she was his only permanent close friend. He seems to have been celibate for the last fifty years of his life.

These unlovely glimpses of a stunted personality are to be found in Donald Spoto's detailed, sympathetically intended The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Little, Brown). Spoto's most arresting—and saddest—new information involves Hitchcock's hopeless fixations on blond leading ladies, from Madeleine Carroll to Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, Vera Miles, and Tippi Hedren. The photography of Bergman in Notorious is the most voluptuous she ever received: one almost laughs when her '40s lipstick is wiped off in the poisoning scenes and the other characters keep telling her how bad she looks—she never looked more beautiful. Bergman and Kelly were evidently spared unwelcome overtures, though Hitchcock took it sourly when they "deserted" him for Rossellini and Prince Rainier. As he grew older, Hitchcock's Victorian reserve began to fray. Vera Miles was put through intensive, exhausting private rehearsals that she found suffocating. She escaped him by becoming pregnant by her husband as Hitchcock prepared to star her in Vertigo—and aroused her Pygmalion's everlasting ire.

His final protegee, the inexperienced Tippi Hedren, was signed to a seven-year contract after Hitchcock spotted her in television commercials. As he began preparing The Birds, he ordered a complete personal wardrobe designed for her in addition to the costumes for her screen test. "It was really very clear, wasn't it?" said Samuel Taylor, the scriptwriter of Vertigo, in which a woman's appearance is made over by the obsessed hero. "He was doing Vertigo with Tippi Hedren."

His sadism now became disturbingly overt. The weeklong filming of the climactic bird attack brought Hedren to an emotional collapse and the film to a temporary shutdown. Hitchcock eventually made a direct sexual proposition during their next movie together, Mamie. Spoto's authority for this ignominious episode is Hedren herself, whose misery is recalled by her co-workers. Everyone on the set saw that something catastrophic had occurred: Hitchcock addressed Hedren ("that girl") only through assistants, lost interest in the film entirely, and wrapped it up posthaste. Spoto, one of the most ardent of Hitchcock admirers, now makes a handsome apology for his tortuous defense of the technical sloppiness and incoherence of the movie in his The Art of Alfred Hitchcock (1976). He was not alone: to the British enthusiast Robin Wood, Mamie was "one of Hitchcock's richest, most fully achieved and mature masterpieces."

Spoto now believes that Hitchcock never recovered from the emotional and professional debacle of Mamie. The actors in Frenzy, his next-to-last film, were repelled by some of the things they were asked to do. Hitchcock's advisers couldn't dissuade him from the explicit filming of the ugly scene of rape and strangulation by the impotent killer; the actors told Spoto they distanced themselves from it by nervously joking together. Hitchcock's sexual anger, first fully expressed in Psycho, had become pathological by this time, and Spoto discreetly revises his earlier praise of Frenzy as a "satisfying" movie, an "admirable achievement" marked by "brilliantly sustained metaphor."

But in The Dark Side of Genius he continues to stake claims on perilously high ground. Hitchcock is compared to Flaubert, Henry James, Rodin, and Hieronymus Bosch. "The scope of the moral tension" in the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much ("a great achievement" in which Doris Day's performance is "flawless") is linked with that in Flannery O'Connor's Wise Blood. The fairground scenes in Strangers on a Train remind Spoto of fairs in the works of Goethe, Bunyan, and Ben Jonson, while the theme of the double, exemplified by Farley Granger and Robert Walker, is traced through Heine, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Stevenson, Wilde, and Dostoyevsky. Hitchcock's fusion of the grotesque and the beautiful is "a merger celebrated by Baudelaire, Joyce, Cocteau and others."

I'll admit this kind of talk is catnip to me, and I'd love to believe it. We have, don't we, two contradictory notions of the artist? First, the avant-garde loner working in silence, exile, and cunning for vindication by posterity: Blake, Joyce, Kafka. Second, the popular entertainer who turns out to have been committing Art without putting on airs: Dickens, the mass-audience serialist, despised for facility and vulgarity, is belatedly recognized as the greatest genius of English literature after Shakespeare (himself a mere popular entertainer in the eyes of his contemporaries). Dickens influenced Dostoyevsky and Kafka, didn't he? In interviews, pulp masters of the Harold Robbins-Sidney Sheldon persuasion regularly invoke Dickens as their ticket to respectability. Who can say what future genius may even now be learning his craft from The Betsy l

This confusion of categories muddies the higher Hitchcock criticism. His poor films as well as his good ones are endlessly analyzable by watchers of literary or academic inclination. In The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, Spoto noticed that the license plate on Janet Leigh's car in Psycho was NFB-418. "Could that stand," he wondered, "for Norman Francis (the saint frequently associated with birds) Bates? He is like a watching bird of prey throughout"—to which my provisional answer would be, "Maybe. But is this useful?" Nevertheless, I can curl up happily with the Hitchcock literature: Truffaut's interviews, in which Hitchcock evades any serious discussion with his perfected television-host flippancy; Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol's pioneering Hitchcock: The First Forty'Four Films (1957), which finds Christian symbolism everywhere; Robin Wood's Hitchcock's Films (1966); and even William Rothman's exhaustive, sometimes deeply cuckoo shot-by-shot analysis of five films, Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze (1982). The experience is slower than watching the films rerun, but almost as much fun as taking a clock apart.

I've seen all of Hitchcock's American films many times and most of his British talkies more than once; of his silents, I know only The Lodger. Vertigo is the one that means most to me. I went to it three nights in a row on its first release and watch for its rare reappearances. Except by Barbara Bel Geddes, who does wonders with a brief role, it is inadequately acted. Kim Novak has a particularly bad patch of Joan Fontaine-ish eyebrow acting in the seaside scene, which one forgives when the character she plays, Madeleine, turns out to have been an impersonation; James Stewart's anguished face-making lacks the detailed domestic urgency of his great performance in Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life. But the movie is an inexorable portrayal of sexual obsession, supported by Bernard Herrmann's Mahlerian score. There are few more painful passages on film than the late scenes in which Stewart transforms Novak into an exact replica of a woman he believes to be dead. Her plaintive "Couldn't you like me—just me the way I am?" stings one's memory.

I rewatch Psycho's first hour and usually stay with it for Anthony Perkins's finely played, nervous interview with Martin Balsam at the motel desk. Notorious is a profound love story ("Great trash, great fun," according to Pauline Kael, one of the more recalcitrant Hitchcock holdouts). The first half of Shadow of a Doubt, before Joseph Cotten's villainy turns mechanical, is always worth seeing. Spoto has an especially interesting passage on the autobiographical references to Hitchcock's British childhood in this ostensibly very American film. The mother Patricia Collinge so touchingly plays is even named after Hitchcock's own mother, who had recently died, and is, Spoto notes, the last sympathetic portrait of a mother in a Hitchcock movie.

Witty performances by Laura Elliott (the girl murdered at the fairground) and Robert Walker make Strangers on a Train intermittently watchable. This film was recently strongly attacked in the gay magazine Christopher Street as a prime instance of Hitchcock's homophobia. Yet Walker is the liveliest character in it. Straights should rise up and picket Hitchcock's dull, perfunctory direction of Farley Granger and Ruth Roman. Maybe because it was the first Hitchcock film I was taken to as a child, I like Rebecca more than devout Hitchcockians do; Dwight Macdonald, no child when it came out, once went out on a limb and called it the most entertaining movie ever made. It might be noticed that a central theme, the transformation of a woman, makes an early appearance—in this case, the young bride's misguided effort to emulate the predecessor her husband in fact hated. The elegant North by Northwest is the most emotionally complex of the chase thrillers. I will even tune in Topaz for Karin Dor's death scene. But there are some I can't do again: the slack, overdressed To Catch a Thief, the drab The Wrong Man, the very pleasant The Lady Vanishes, The Man Who Knew Too Much in either version.

Spoto's biography contains a provocative remark from the novelist Brian Moore, who signed on as scriptwriter for one of Hitchcock's worst films, Torn Curtain, and came to regret it. "It's obvious Hitchcock had an interesting mind," Moore generously recalled. "He's the film director who is most like a writer, insofar as he creates his films alone in a room—and that, for him, is the process of filmmaking." One of Hitchcock's repeated statements to that effect has become notorious: "I wish I didn't have to shoot the picture. When I've gone through the script and created the picture on paper, for me the creative job is done, and the rest is just a bore." The thorough planning of his films eliminated improvisation or on-theset chances a director like Renoir or Altman might welcome and make use of.

Hitchcock's aim was to inflict surprise and uncertainty on his audiences; in doing this, he exorcised demons of his own that we recognize more clearly after reading Spoto's biography. But isn't this tight, fearful control a mark of the skilled minor artist? The world in Hitchcock's movies is, with rare exceptions, a narrow, chilly, loveless one. Shaky on human motivation—as his scriptwriters kept learning to their dismay—he cared most about film technique and knew a few feelings intimately: panic, insecurity, betrayal, and sexual obsession. One watches his films over and over again for these elements. He was the most expert of mousetrap makers. His accomplishment was not negligible. A mousetrap skillfully set, Hamlet told us, can catch a conscience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now