Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMrs. Fish's Ape

Society and Hospitality in New York, 1983: Vignettes and Reflections

Michael M. Thomas

"Mirror, mirror, on the wall, What makes society come to call?" “Honey," says the candid glass, “It takes cash, and names; But it don't take class."

—anonymous Manhattan doggerel, 1983

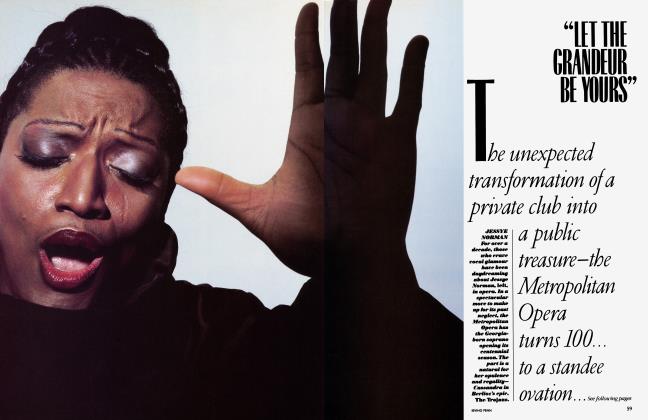

TO hear the experts talk, or to read the papers, would almost convince one that New York is experiencing a second golden age of the dinner party. Perhaps not since the turn of the century, the halcyon party-giving era dominated by the likes of Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, have so many striving hostesses, awash in rich husbands and ambition, thrown taste and discretion to the winds in pursuit of social recognition. One must of course make allowances for the drift of time. Mrs. Fish once gave a lavish dinner for the Prince del Drago, who on close inspection turned out to be a monkey. We must assume that Mrs. Fish’s ape enjoyed the evening and the adulation, and that the next morning he was returned to the zoo. Things haven’t changed much, except that today’s monkeys don’t go back to a cage, but more likely to the executive suite of a major corporation or to one of the great Washington chanceries.

September will kick off a new social season. There will be new paper fortunes to be spent. At least two Texas ladies can be discerned on the horizon, steaming toward prominence and mention in the columns with the majesty of dreadnoughts. We can also count on a passel of Lebanese and South Americans to add their particular spice to things. Thanks to OPEC, Dow Jones, inflation, Reaganomics, and, above all, monetarism (the Black Death of the age, which makes realtors and stockbrokers the nobility of our great enterprise), the supply of multimillionaires has expanded more rapidly than at any time in history. The; field will therefore be crowded; the glittering prizes will be claimed by the swift, the agile, the driving— and the studious. In life—or party giving—as in art, we learn by studying the works of the masters of an era, so that is where we must go for instruction.

As we pause at the threshold of the Grande Galerie of current hostessing, it pays to bear in mind a few general rules. The first is that any important dinner must have a point beyond a simple desire to feed and entertain one’s friends: most parties are given to honor the ambition and purchasing power of the host and hostess, but it’s ever so much more acceptable to mask this by declaring that a given evening is dedicated to the Honorable or Signor or Madame So-and-so. Also, the etiquette of power party giving today permits important guests to deliberate acceptance in terms of their own significance; angels asked to (dance on the head of a particular evening’s pin are reassured that any other angels thereon waltzing will be equally important. Finally, a dedicated evening will qualify for a tax deduction: in a society in which avoidance of taxes is at least as highly regarded as the skills which make the money to be taxed, this counts.

PORTRAIT OF A HOSTESS

Let us begin with Mrs. Gesternblatt, she of the legendary at-homes. Loosely translated from German, the name means “yesterday’s news,” which may well be her social destiny, but for the moment she is on everyone’s lips and list. Her social career, a matter of a couple of years at best, constitutes a postgraduate course in how to make it in postinflationary Manhattan society.

Mr. Gesternblatt is a prince of the paper merchants, a titan among those who have grasped that the tools of fortune are a telephone and the use of someone else’s money, and not the invention and manufacture of a desirable, functional product at a competitive price. He has recently scored a big financial coup, sufficient to underwrite a commensurate social triumph orchestrated by his wife. His money and Mrs. Gesternblatt arrived in his life at about the same time, a conjunction that mean-spirited types, who have no feeling for romance, continue to insist on mentioning.

As a hostess, Mrs. Gesternblatt has found her true vocation. The naysayers mutter that she found it early and got in a lot of practice at 30,000 feet, but pay no mind to them. They need their daily ration of Schadenfreude the way health nuts need their granola. The fact is, Mrs. Gesternblatt and the age are made for each other; she fits contemporary life like a tiny foot in a glass slipper. If she didn’t exist, we—or, more properly, Gesternblatt—would have had to invent her. Any era needs all sorts of forms of leadership if it is to demonstrate the widest range of its potentialities and propensities for good or evil, for wisdom or foolishness, for whatever it is that the spirit of the age is moved to create out of whatever resources it has. The truly inspiring leader, whether in the political, mercantile, or (in this instance) social sphere, will both understand and incarnate his age. Which is what, in this time, in this place, Mrs. Gesternblatt does.

To begin with, she instinctively understands New York. There are, generally speaking, three circles of power—three oligopolies, if you will—in the city today. The first involves a sort of double helix which entwines politics and money. If you want to see it at work, show up any weekday morning at the Regency Hotel and watch the public space and weal being bartered away over breakfast. The second is fundamentally consultative; its power is almost exclusively inferential, as is, frankly, most power outside the White House or the Mafia. It makes or breaks few real deals, but it does make enough noise to command more respect than the facts would justify. David Rockefeller and Dr. Henry Kissinger are its luminaries. The third interweaves the philanthropic oligopoly with the first two; it controls access to the more coveted boards and trusteeships; it dispenses the now rather worn laurel of social acceptance and acceptability. Because it is the only one of the three power circles in which women exercise day-to-day leadership, it is the hunting ground of ambitious ladies who wield caterers, advisers, and social columnists in much the same manner as the Angles and Saxons once took after each other with battle-axes. The social nexus at which these circles most frequently intersect is the power dinner party— where Mrs. Gesternblatt proposes to assert her ascendancy.

At a Gesternblatt evening, there lurks a sense of business being done. The IRS man haunts these dining rooms like Banquo’s ghost. The guests are deductible, as are the canapes, the Chateau Mouton-Rothschild, the strolling buskers. Toasts are given, often at wearying length. In a sense, the old awards dinners have come out of the cold of hotel ballrooms and into the best dining rooms of Sutton Place and Park Avenue. The elevator discharges us into the Gesternblatt foyer. It only takes one sniff, one glance around, to know that the days of coffee, tea and milk are forever behind our hostess. Du cote de chez Gesternblatt, everything is vintage, even the Lavoris.

And what a du côté, what a chez! The apartment is a famous Fifth Avenue triplex that has been transformed into a shimmering miracle of marble and glass. The effect is dazzling; one feels as if one has been transported to the interior of a giant urinal. The furniture, mostly French, all eighteenth century and earlier, is extraordinary. Such garniture; such bergeres, etageres, veilleuses, tabourets, commodes. The effect is so total and tasteful, we’ll just overlook waggish comments that until a month ago Mrs. Gesternblatt thought commodes were signed “Crane” and “American-Standard” instead of “Riesener” and the other lofty names found in art history books.

A heady odor assaults the senses. Orchids, of course. Mrs. Gesternblatt is to the city’s orchid growers what Brooke Astor is to its elephants. Look around. There are more cymbidiums here than in the Oahu Hilton; one half expects The Don Ho Show to begin at any moment. And speaking of tiny bubbles, have some of this specially bottled Dom Perignon as we make our invisible way through the gathering throng. It’s a typical Gesternblatt crowd. Isn’t that Dr. Kissinger there? And, hanging on his words, the Rover Boys of the economic nostrum crowd who publish their panaceas in The New York Review of Books, the Playbill of the city’s power elite? There’s a top officer of one of the city’s premier cultural bastions, an extra man so much in demand that he’s already worn the wings off a dozen pairs of shoes and it’s barely May. An assortment of other bootlickers and lickees fill out the company.

Look over here. A silver trolley that once bore the roast beef of Old England now displays the caviar of Old Russia, mounds of it. While it’s not quite up to Gstaad standard, where one is offered the choice of gray Iranian or black Russian, it’ll do, especially given the imaginative fillip of being served up with an ice cream scoop. In fact, the distinguishing quality of Mrs. Gesternblatt’s evenings is their imaginative vitality, which is why, I think, hers work, while better-heeled, betterbred women put on the dog and end up with mongrels.

This has nothing to do with taste. Taste, for example, can draw the line between extravagance and ostentation, and, in turn, between ostentation and exhibitionism, which Mrs. Gesternblatt frequently cannot. One wonders also, given what is said the next morning (over telephone exchanges still known to their subscribers as Butterfield 8 or Trafalgar 9...), whether Mrs. Gesternblatt has properly judged all her new, rapacious friends. It’s the old dilemma of crashing the upper reaches of the philanthropoly; they’ll drink your Lafite and munch your smoked fish and air-kiss you upside your head, but when it comes to joining the club, you take whom and what you are given. They may bring you right up to the big ball club, the Metropolitan Museum or Sloan-Kettering, or farm you out to some high-sounding but inconsequential civic group for seasoning. Nevertheless, a lot of Gesternblatt fish eggs have disappeared down throats that the next morning have been pretty busy disparaging their hostess. This may be, however, the price that must be paid if one wants so desperately whatever it is Mrs. Gesternblatt wants.

A Gesternblatt evening is, above all, an event. In no particular is this as apparent as in the food. It’s exotic; it’s inventive; it’s expensive beyond imagining; it’s a fantasy. Roe of oyster; truffles spread around like Fritos; partridges en brioche; salmis of hare, pheasant, antelope; a cheese board that would daunt General de Gaulle; whatnots of sugar spun to a fineness that a Murano glassblower would envy. Great vintages of claret and Rhenish cascade down aristocratic throats with the foamy fury of the Reichenbach Falls. It’s extravagant. It’s wondrous strange to behold. And yet, despite all the muttering going on around town behind aristocratic hands, it works. Sure it’s a circus. There are tightwire walkers (real estate and commodity speculators); hawkers and barkers (stockbrokers and art dealers working the room); even clowns (heads of major banks). So what? To the chagrin of many, the Gesternblatts get the best audience in town. They get the really big Greeks and Italians and South Americans. They get whoever’s hot on Wall Street. They get the thin, pale, azure-dyed fluid that passes for blue blood these days. They get hookers posing as ladies, and ladies who act like hookers. They don’t work the arts; few poets, painters, playwrights scarf Gesternblatt’s duck liver mousse. They do get the odd interior decorator or dress designer, which comes to the same thing in these circles.

Why? Why do the Gesternblatts consistently draw the best, the biggest names? That’s the question with which envious ladies torment themselves. A number of answers are offered. One professional partygoer believes it’s because it’s such a great show. It appeases the overseas types because it’s vulgar, splashy, Unsinkable Molly Brown America brought to life. It salves the demurely tormented psyches of the old rich, who’d like to have a real blowout with their own money instead of feeling duty-bound to give it to some hospital rather than laying on the Dom Perignon. The oldveau riche have a thousand answers to excuse their constant attendance at the Gesternblatts. The fact is that there they have the kind of fun with money that they were always told was indecent. Lost in a frenzy of balloons and champagne and strolling mariachis, their ears are deafened to the in-grave whirring of their stern Presbyterian grandfathers.

Perhaps not since the turn of the century have so many striving hostesses thrown taste and discretion to the winds in pursuit of social recognition”

Although Mrs. Gesternblatt is a quick and omnivorous study, all is not yet perfect, although it improves daily. For one thing, there aren’t any serious paintings, although there’s space enough on the wall to quicken a thousand dealers’ hearts. Gesternblatt can go a couple of hundred grand for a bureau plat, but he’s not yet in the Manet-MonetCezanne league; the Gesternblatts sat out the Havemeyer sale, but another year of this kind of stock market and there’ll be a decent Degas or Canaletto filling the luminously reflective space in which le tout Manhattan now examines its lipstick. The makeover of the lady of the house is coming along nicely. It may be that nothing can be done about the Choctaw in the cheekbones, but the voice, which once could plane a two-by-four, now manages a lispy susurrus that would do credit to a Chapin School fourthgrader. There’s still too much in the way of tiaras and velvet bustles, but she’ll learn. Those are easy to fix— little gaucheries that aren’t critical to the obstreperous vulgarity which is her priceless asset as a hostess.

OTHERS IN THE FIELD

While she has no peers, Mrs. Gesternblatt has a couple of would-be rivals. One is Madge Brush. Where Mrs. Gesternblatt does it mainly with money, Madge does it with mirrors. Mrs. Brush’s clout derives from a brief marriage that introduced her to Embassy Row in Washington, which is still the well from which she draws her matchless guest lists. And matchless they are! While the focal point, the essence and main attraction, of a Gesternblatt evening is unquestionably money and what and whom it buys, the doors of Mme. Brush’s relatively modest Gracie Square apartment are thrown open to reveal a spectacle that is pretty ordinary. The food’s O.K.; the wine’s not much better; but, oh boy, the place is crammed with big-timers! There’s an odor in the room more intoxicating than that of a million Gesternblatt orchids: politics. Not Gracie Mansion stuff; bigger than that, and Albany too; the biggest, in fact: 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. Madge has a whole lot of due bills out along the Potomac; the big hitters are only too happy to pay her back; always running, they’re delighted to act as centerpieces around which she can build the kind of guest list that can come up with the cash and the ink. Everybody has heard about the sort of people who turn up at Madge’s. She’s been placed under the patronage of the exquisitely cantilevered woman who is the city’s leading gossipist, and the publicity hasn’t hurt. People push and shove for invitations. Madge’s parties are less fun than the Gesternblatts’. The sole point is for one to be seen and known to be there, and to leave after dinner. The verdict of the New Yorker contingent on the Washington Ozymandiae who stand above the crowd like oversized epergnes, secure in their envelope of selfesteem, is that they are “charming.” To me, that doesn’t match up to the Gesternblatt caviar. Charm is cheap. But when you’re talking beluga, you’re talking money.

And there are others. The Pudding of the Aegean, for instance—a Cretan lady playwright whom people describe as “statuesque” when they want to be kind. Her charmless, lifeless parties draw a perfectly respectable list—no one absolutely top drawer, you understand—and they are large, but that’s all. They’re the sort of evening immortalized by the now dead society wit who, on entering a particularly pretentious Palm Beach party, inquired of his hostess, “Did you invite these people, or advertise for them?” Then there are the one-note hostesses: this one is famous for her wine; another for her flowers; another for her pictures; another for the astonishing, compelling hideousness of her apartment; another for a husband more soporiferous than Nembutal.

Only Mrs. Gesternblatt puts it all together, however. She is successful precisely because of her unapologetic store-bought showing off, not in spite of it. In his valuable book Prejudices, Robert Nisbet speculates that there may be “ ‘shameless cultures,’ ones so lacking in capacity for shame that effrontery not only ceases to be offensive to a people but becomes actually welcome.” He goes on to state: “The United States is without doubt in one of its periods of rampant effrontery...probably the most fertile period in this respect since Mark Twain’s Gilded Age_” Mrs. Gesternblatt’s success is a rare and perfect symptom of the present condition of our 100 percent money-based moral culture. Like Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel, or Werther, or The Rites of Spring, she reflects her moment so completely and resonantly that she seems to define it. Therein is her triumph. It may seem a questionable achievement, in pursuit of a dubious goal, but think about it. Others have achieved a lot less with a lot more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now