Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRobert Fitzgerald

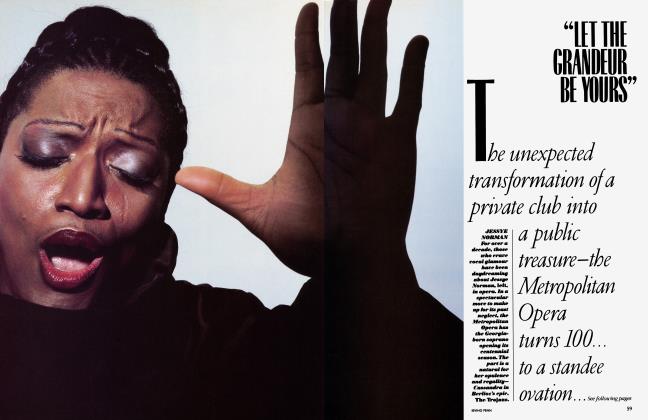

AT THE TOP

Translation is a noble art, as Robert Fitzgerald learned early on. In the 1930s he was a Harvard undergraduate brushing up his Latin. “One day I ventured a colloquial, a free translation of some lines from Virgil. The professor swiveled his chair and looked out the window—to spare himself at least the sight of me—then turned, with a catlike smile, and said, 'An ignoble effort, Mr. Fitzgerald.’”

Fitzgerald went on to become a classicist, poet and teacher; he taught at Harvard for many years. His verse translations of the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer gave us the breath and immediacy of the originals. Now, at seventy-two, with the publication of his Aeneid this month, he becomes the first poet to translate the entire classical trinity into English. We asked this self-deprecating, charming and mischievous man the preposterous question, Why should anyone read Virgil today? "Why?" he responded. "It’s good reading, that’s why."

a

eneid VI, 237-314)

THE DESCENT TO

THE UNDERWORLD

The cavern was profound, wide-mouthed, and huge, Rough underfoot, defended by dark pool And gloomy forest. Overhead, flying things Could never safely take their way, such deathly Exhalations rose from the black gorge Into the dome of heaven. The priestess here Placed four black bullocks, wet their brows with wine, Plucked bristles from between the horns and laid them As her first offering on the holy fire, Calling aloud to Hecate, supreme In heaven and Erebus. Others drew knives Across beneath and caught warm blood in bowls. Aeneas by the sword’s edge offered up To Night, the mother of the Eumenides, And her great sister, Earth, a black-fleeced lamb, A sterile cow to thee, Proserpina. Then for the Stygian king he lit at night New altars where he placed over the flames Entire carcasses of bulls, and poured Rich oil on blazing viscera. Only see: Just at the light’s edge, just before sunrise, Earth rumbled underfoot, forested ridges Broke into movement, and far howls of dogs Were heard across the twilight as the goddess Nearer and nearer came.

“Now keep away,”

The Sibyl cried, “all those unblest, away! Let all the grove be cleared! But you, Aeneas, Enter the path here, and unsheathe your sword. There’s need of gall and resolution now.”

She flung herself wildly into the cave mouth, Leading, and he strode boldly at her heels. Gods who rule the ghosts; all silent shades; And Chaos and infernal Fiery Stream, And regions of wide night without a sound, May it be right to tell what I have heard, May it be right, and fitting, by your will, That I describe the deep world sunk in darkness Under the earth.

Now dim to one another

In desolate night they walked on through the gloom, Through Dis’s homes all void, and empty realms, As one goes through a wood by a faint moon’s Treacherous light, when Jupiter veils the sky And black night blots the colors of the world.

Before the entrance, in the jaws of Orcus, Grief and avenging Cares have made their beds, And pale Diseases and sad Age are there, And Dread, and Hunger that sways men to crime, And sordid Want—in shapes to affright the eyes— And Death and Toil and Death’s own brother, Sleep, And the mind’s evil joys; on the doorsill Death-bringing War, and iron cubicles Of the Eumenides, and raving Discord, Viperish hair bound up in gory bands. In the courtyard a shadowy giant elm Spreads ancient boughs, her ancient arms where dreams, False dreams, the old tale goes, beneath each leaf Cling and are numberless. There, too, About the doorway forms of monsters crowd— Centaurs, twiformed Scyllas, hundred-armed Briareus, and the Lernaean hydra Hissing horribly, and the Chimaera Breathing dangerous flames, and Gorgons, Harpies, Huge Geryon, triple-bodied ghost. Here, swept by sudden fear, clutching his sword, Aeneas stood on guard with naked edge Against them as they came. If his companion, Knowing the truth, had not admonished him How faint these lives were;—only images Hovering bodiless—he had attacked And cut his way through phantoms, empty air.

The path goes on from that place to the waves Of Tartarus’s Acheron. Thick with mud, A whirlpool out of a vast abyss Boils up and belches all the silt it carries Into Cocytus. Here the ferryman, A figure of fright, keeper of waters and streams, Is Charon, foul and terrible, his beard Grown wild and hoar, his staring eyes all flame, His sordid cloak hung from a shoulder knot. Alone he poles his craft and trims the sails And in his rusty hull ferries the dead, Old now—but old age in the gods is green.

Here a whole crowd came streaming to the banks, Mothers and men and forms with all life spent Of heroes great in valor, boys and girls Unmarried, and young sons laid on the pyre Before their parents’ eyes—as many souls As leaves that yield their hold on boughs and fall Through forests in the early frost of autumn, Or as migrating birds from the open sea That darken heaven when the cold season comes And drives them overseas to sunlit lands. There all stood begging to be first across And reached out longing hands to the far shore.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now