Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLEARNING TO SEE

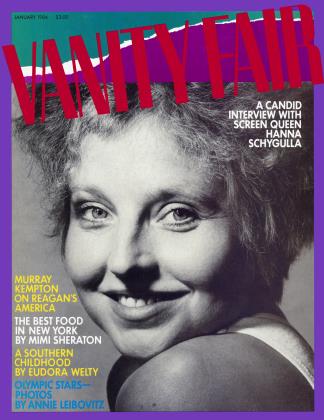

Eudora Welty

Crossing borders of memory and imagination, America's greatest storyteller takes a back-roads journey into her past

When we set out in our five - pa 5senger Oak land touring car on our summer trip to Ohio and West Virginia to visit the two families, my mother was the navigator. She sat at the alert all the way at Daddy's side as he drove, correlating the AAA Blue Book and the speedometer, often with the baby on her lap. She'd call out, "All right, Daddy: '86-point-2, crossroads. Jog right, past white church. Gravel ends—' And there's the church!" she'd say, as though we had scored. Our road always became her adversary. "This doesn't surprise me at all," she'd say as Daddy backed up a mile or so into our own dust on a road that had petered out. "I could've told you a road that looked like that had little intention of going anywhere."

"It was the first one we'd seen all day going in the right direction," he'd say. His sense of direction was unassailable and every mile of our distance was familiar to my father by rail. But the way we set out to go was popularly known as "through the country."

My mother's hat rode in the back with the children, suspended over our heads in a pillowcase. It rose and fell with us when we hit the bumps, thumped our heads and batted our ears in an authoritative manner when sometimes we bounced as high as the ceiling. This was 1917 or 1918; a lady couldn't expect to travel without a hat.

Edward and I rode with our legs straight out in front of us over some suitcases. The rest of the suitcases rode just outside the doors, strapped on the running boards. Cars weren't made with trunks. The tools were kept under the back seat and were heard from in syncopation with the bumps; we'd jump out of the car so Daddy could get them out and jack up the car to patch and vulcanize a tire, or haul out the tow rope or the tire chains. If it rained so hard we couldn't see the road in front of us, we waited it out, snapped in behind the rain curtains and playing Twenty Questions.

My mother was not naturally observant, but she could scrutinize: when she gave the surroundings her attention, it was to verify something—the truth or a mistake, hers or another's. My father kept his eyes on the road, with glances toward the horizon and overhead. My brother periodically stood up in the back seat with his eyelids fluttering while he played the harmonica, "Old MacDonald Had a Farm" and "Abdul the Bulbul Amir," and the baby slept in Mother's lap and only woke up when we crossed some rattling old bridge. "There's a river!" he'd crow to us all. "Why, it certainly is," my mother would reassure him, patting him back to sleep. I rode as a hypnotic, with my set gaze on the landscape that vibrated past at twenty-five miles an hour. We were all wrapped by the long ride into some cocoon of our own.

The journey took about a week each way, and each day had my parents both in its grip. Riding behind my father I could see that the road had him by the shoulders, by the hair under his driving cap. It took my mother to make him stop. I inherited his nervous energy in the way I can't stop writing on a story. It makes me understand how Ohio had him around the heart, as West Virginia had my mother. Writers and travelers are mesmerized alike by knowing of their destinations.

And all the time that we think we're getting there so fast, how slowly we do move. In the days of our first car trip, Mother proudly entered in her log, "Mileage today: 161!"

"A Detroit car passed us yesterday." She always kept those logs, with times, miles, routes of the day's progress, and expenses totaled up.

That kind of travel made you conscious of borders. Crossing a river, crossing a county line, crossing a state line—especially crossing the line you couldn't see but knew was there, between the South and the North, you could draw a breath and feel the difference.

The Blue Book warned you of the times for the ferries to run; sometimes there were waits of an hour between. With rivers and roads alike winding, you had to cross some rivers three times to be done with them. Lying on the water at the foot of a riverbank would be a ferry no bigger than somebody's back porch. When our car had been driven on board—often it was down a roadless bank, through sliding stones and runaway gravel, with Daddy simply aiming at the two-plank gangway—father and older children got out of the car to enjoy the trip. My brother and I got barefooted to stand on wet, sun-warm boards that, weighted with our car, seemed exactly on the level with the water; our feet were the same as in the river. Some of these ferries were operated by a single man pulling hand over hand on a rope bleached and frazzled as if made from corn shucks.

I watched the frayed rope running through his hands. I thought it would break before we could reach the other side.

"No, it's not going to break," said my father. "It's never broken before, has it?" he asked the ferryman.

"No sirree."

"You see? If it never broke before, it's not going to break this time."

His general belief in life's wellbeing worked either way. If you had a pain, it was, "Have you ever had it before? You have? It's not going to kill you, then. If you've had the same thing before, you'll be all right in the morning."

My mother couldn't have more profoundly disagreed with that.

"You're such an optimist, dear," she often said with a sigh, as she did now on the ferry.

"You're a good deal of a pessimist, sweetheart."

"I certainly am."

And yet, I was well aware as I stood between them with the water running over my toes, he the optimist was the one who was prepared for the worst, and she the pessimist was the daredevil: he the one who on our trip carried chains and a coil of rope and an ax all upstairs to our hotel bedroom every night in case of fire, and she the one who—before I was born—when there was a fire, had broken loose from all hands and run back—on crutches too—into their burning house to rescue her set of Dickens, which she flung, all twenty-four volumes, from the window before she jumped out after them, all for Daddy to catch.

"I make no secret of my lifelong fear of the water," said my mother, who on ferryboats remained inside the car, clasping the baby to her—my brother Walter, who was destined to prowl the waters of the Pacific Ocean in a minesweeper.

As soon as the sun was beginning to go down, we went more slowly. My father would drive sizing up the towns, inspecting the hotel in each, to decide where we could safely spend the night. Towns little or big had beginnings and ends; they reached to an edge and stopped where the country began again as though they hadn't happened. They were intact and to themselves. You could see a town lying ahead in its whole, as definitely formed as a plate on a table. And your road entered and ran straight through the heart of it; you could see it all, laid out for your passage through. Towns, like people, had clear identities and your imagination could go out to meet them. You saw houses, yards, fields, and people busy in them, the people that had a life where they were. You could hear their bank clocks striking, you could smell their bakeries. You would know those towns again, recognize the salient detail, seen so close up. Nothing was blurred, and in passing along Main Street, slowed down from twenty-five to twenty miles an hour, you didn't miss anything on either side. Going somewhere "through the country" acquainted you with the whole way there and back.

My mother never fully gave in to her pleasure in our trip—for pleasure every bit of it was to us all—because she knew we were traveling with a loaded pistol in the pocket on the door of the car on Daddy's side. I doubt if my father fired off any kind of gun in his life, but he could not have carried his family from Jackson, Mississippi, to West Virginia and Ohio through the country, unprotected.

This was not the first time I'd been brought here to visit Grandma in West Virginia, but the earlier visits I barely remembered. Where I stood now was inside the house where my mother had been born and where she grew up. It was a low, gray-weathered wooden house with a broad hall through the middle of it with the light of day at each end, the house that my grandfather Ned Andrews had built to stand on the very top of the highest mountain he could find.

"And here's where I first began to read my Dickens," Mother said, pointing. "Under that very bed. Hiding my candle. To keep them from knowing what I was up to all night."

"But where did it all come from?" I finally asked her. "All that Dickens?"

"Why, Papa gave me that set of Dickens for agreeing to let them cut off my hair," she said, as if surprised that a reason like that wouldn't have occurred to me. "In those days, they thought very long thick hair like mine would sap a child's strength. I said No! I wanted my hair left the very way it was. They offered me gold earrings first—in those days little girls often developed a wish to have their ears pierced and fitted with little gold rings. I said No! I'd rather keep my hair. Then Papa said, 'What about books? I'll have them send a whole set of Charles Dickens to you, right up the river from Baltimore, in a barrel.' I agreed."

Ned Andrews had been Clay County's youngest member of the bar. He quickly made a name for himself on the side as an orator. When he gave the dedicatory address for the opening of a new courthouse in Nicholas County, West Virginia, my mother put away a copy. He is praising the architecture of the building:

The student turns with a sigh of relief from the crumbling pillars and columns of Athens and Alexandria to the symmetrical and colossal temples of the New World. As time eats from the tombstones of the past the epitaphs of primeval greatness, and covers the pyramids with the moss of forgetfulness, she directs the eye to the new temples of art and progress that make America the monumental beacon-light of the world.

People may have expected the highfalutin in oratory in those days, but they might not have expected Ned's courtroom flair. There was a murder trial of a woman given to fortune telling. She had been overheard reading in an old man's cards that his days were numbered. When, the very next day, this old man had been found dead in his bed from a gunshot wound, it appeared to the public that that fortune teller might have known too much about it. She was put on trial for murder. Ned Andrews's defense centered on the well-known fact that the old man kept his loaded gun mounted at all times over the head of his bed. This was the gun that had shot him. The old man could have discharged it perfectly easily himself, Ned argued, by carelessly bouncing on the bed a little bit. He proposed to prove it, and invited the jury of dubious mountaineers to watch him do it. Leading them all the way up the mountain to the old man's cabin, he mounted the gun in place on its rests, having first loaded it with blank shells, and while they watched, he mimicked the old man and made a running jump onto the bed. The gun jarred loose, tumbled down, and fired at him. He rested his case. The fortune teller was, without any more ado, declared not guilty.

He was brim full of talents. He'd attended Trinity College (later, Duke University), where he organized a literary society; he'd been a journalist and a photographer in Norfolk, Virginia, and in West Virginia where he'd run away to, to seek adventure, he'd turned into a lawyer. He seems to have been a legendary fisherman in those mountain streams, is still now and then referred to in local sportsmen's tales. Ned was impervious to the sting of bees and could always be summoned to capture a wild swarm. Ned was the one they sent for when someone fell down an empty well, because he was not afraid to harness himself and be lowered into the deathly gases at the bottom and bring the unconscious victim up again.

And the human failings Mother could least forgive in other people, she regarded with only tenderness in him. I gathered—slowly and over the years I gathered—that sometimes he drank. He told tall tales to his wife. He told one to begin with, in order to marry her, saying he was of age to do so, when he was nineteen and four years younger than she. She was superstitious; he loved to tease her with tricks, to stage elaborate charades, with the connivance of one or two of his little boys, that preyed on her fear of ghosts. He shocked her with a tale—Mother said there was nothing to prove it wasn't a fact—that one of the Andrews ancestors had been hanged in Ireland. Eudora Carden, my grandmother, came from the home of a strongly dedicated Baptist preacher, and about all preachers Ned was irreverent and irrepressible. I have seen photographs he took of her—tintypes; it's clear that he took them with great care to show how beautiful he found her. In one she is standing up behind a chair, with her long hands crossed at the wrist over the back of it; she is dressed in her best, with her dark hair drawn high above her oval face and tucked with a flower that looks like a wild rose. She is very young. She has long gray eyes over high cheekbones; she is gazing to the front, looking straight at him. Her mouth is sensitive, her lips youthfully full. She told her daughter Chessie years later that she was objecting to his taking this picture because she was pregnant at the time, and the pose—the crossed hands on the back of a chair—had been to hide that. (With my mother, I wondered, Chessie, her first child?) When she came back from the well on cold mornings, her hands would be bleeding from breaking the ice on it: this is what my mother would remember when she looked at those soft hands in the tintype.

I don't know from whom it came or to whom it was passed, but at one time an old, homemade drawing of the Andrews family tree came into my mother's hands. It was rolled up; if unrolled it could rattle shut the next instant. The tree was drawn as a living tree, spreading from a rooted trunk, every branch, twig, and leaf in clear outline, all with names and dates on them in a copperplate handwriting. The most riveting feature was the thick branch stemming from near the base of the main trunk: it was broken off short to a jagged end, branchless and leafless, and labeled "Joseph, Killed by Lightning.''

It had been executed with the finest possible pen, in ink grown very pale, as if it had been drawn in watered maple syrup. The leaves weren't stiffly drawn or conventional ellipses, all alike, but each one daintily fashioned with a pointed tip and turned on its stem this way or that, as if this family tree were tossed by a slight breeze. The massed whole had the look, to me at that time, of a children's puzzle in which you were supposed to find your mother. I found mine—only a tiny leaf on a twig of a branch near the top, hardly big enough to hold her tiny name.

The Andrews branch my mother came from represents the mix most usual in the Southeast—English, Scottish, Irish, with a dash of French Huguenot. The first American one, Isham, who fought in the Revolutionary War, was born in Virginia and moved to Georgia, where succeeding generations lived. The Andrewses were not a rural clan, like the Weltys; they lived in towns, were educators and preachers, with some Methodist circuit riders; one cousin of Ned's (Walter Hines Page) was an ambassador to England. By the time my mother's father, Edward Raboteau Andrews—Ned—was born in 1862, the family had returned to Virginia. He broke from the mold and at eighteen ran away from a home of parents, grandparents, sisters, brothers, and aunts in Norfolk to become the family's first West Virginian.

Here in the center of the Andrews kitchen, at the same long table where the family always ate, not too far from where Grandma seemed to be always busy at the warm stove, Ned Andrews had sat and worked up his cases for the defense in Clay Courthouse, far below and out of sight straight down the mountain. Mother remembered him transposing band music there too; he had sent off for the instruments, got together a band, and proceeded to teach them to play in concert, lined up on the courthouse lawn: he entertained a strong love of music. His children had an instrument each to learn to play too: he assigned my mother the cornet. (When I think back to how she sang "Blessed Assurance" while washing the dishes,

I realize she flatted her high notes just where a child's cornet might.)

It was in the quilted bed in the front room of this house where he lay in so much pain (probably from the affliction that brought on his death, an infected appendix) that he once told Mother, a little girl, to bring the kitchen knife and plunge it into his side; she, hypnotized, almost believed she must obey. It was from that door she went with him on the frozen winter night a few years later when it was clear he had to get, somehow, to a hospital. This meant Baltimore. The mountain roads were impassable, there was ice in the Elk River, but a neighbor vowed he could make way by raft. She was fifteen. Leaving her mother and the five little brothers at home, Chessie went with him. Her father lay on the raft, on which a fire had been lit to warm him, Chessie beside him; the neighbor managed to pole the raft through the icy river and eventually across it to a railroad. They flagged the train. It seems likely the place where they flagged it was where (and this memory I carry of an earlier visit at age three) my mother and I were let off it on the early summer dawn and saw the five grown-up brothers waiting with the horse and farm wagon on the other side of the mist-covered river, when my mother rang the iron bell and we watched the boat come toward us out of the mist.

My mother had returned by herself from Baltimore, her father's body in a coffin on the same train. He had died on the operating table in Johns Hopkins, of a ruptured appendix, at thirty-seven years of age.

The last lucid remark he'd made to my mother was, "If you let them tie me down, I'll die." (The surgeon had come out where she stood waiting in the hall. "Little girl," he'd said, "you'd better get in touch now with somebody in Baltimore." "Sir, I don't know anybody in Baltimore," she'd said, and what she never forgot was his astounded reply: "You don't know anybody in Baltimore?")

It was from this house that my mother very soon after that piled up her hair and went out to teach in a one-room school, mountain children little and big alike. She left riding from home every day on her horse; since she had the river to cross, a little brother rode on her horse behind her to ride him home, while she rowed across the river in a boat. And he would be there to meet her with her horse again at evening. All this way, to pass the time, she told me, she recited the poems in McGuffey's Readers out loud.

She could still recite them in full when she was lying helpless and nearly blind, in bed, in old age. Reciting, her voice took on resonance and firmness, it rang with the old fervor, with ferocity even. She was teaching me one more, almost her last, lesson: emotions do not grow old. I knew that I would feel as she did, and I do.

Teaching, she earned, little by little, money enough to go to nearby Marshall College in the summers and in time was graduated. Her mind was filled with Paradise Lost, she told me later, showing me the notebook she still kept with its diagrams. It was as a schoolteacher she'd met my father, a young man from Ohio who had come to work that summer in the office of a lumber company in the vicinity. While they courted, they used to take long walks up and down the railroad tracks, which I imagine my father found in themselves romantic—they took snapshots of each other, my father with one foot on a milepost, my mother sitting on a stile with an open book and wearing a "fascinator" over her hair. My father had her snap his picture standing on a moving sidecar, his hand at the lever. It was from this house that she married him and set off for a new life and a new part of the world for both of them, in Jackson, Mississippi.

Mother's brothers were called "the boys." Their long-necked banjos hung on pegs along the wide hall, as casually as hats and coats. Coming in from outdoors, Carl and Mose lifted their banjos off the wall and sat down side by side and struck in. They were what I remembered, along with the mist-hidden river, from my early visit; I had till now forgotten. They played together like soul mates. At age three, I'd cried, "Two Carls!" They sang in the same perfect beat, perfect unison, "Frog Went A-Courting and He Did Ride."

That effortless, drumlike rhythm, heard in double too, would have put a claim on any child. They had a repertoire of ballads and country songs and rousing hymns. My mother would tell her brothers, plead with them, to stop—I didn't want to go to bed. "Aw, Sister, let Girlie have her one more song," and one song could keep going without loss of a beat into still one more.

The boys liked to sing together too, all five, without accompaniment. Gus, the heaviest, with his broad chest, dominated the others with a bass down to his toes. Those old hymns they'd grown up with, coming out chorus after chorus, sounded more and more uproarious, especially sung outdoors. "Roll, Jordan, Roll" would fill the air around them and roll back on them from the next mountain in echoes, as if the mountain were full of singers, like blackbirds in a pie, just waiting for the song to let them out.

I don't suppose now that my mother ever thought of her father in any other light than the one she saw him in when she was a little girl—for he didn't live much beyond then. All I was given to know of him myself is her same childlike vision, uncorrectable—half of it adoring dream, half brutal memory of his death, the part of his story that she, all by herself, was the one able to tell. Her brothers were too little to have kept a clear memory of him; they remembered his songs best, remembered him when they sang, and told how he made up more and more verses to "Where Have You Been, Billy Boy?" putting his own rambunctious words to the tune. What they remember is what the stories tell about him.

What did my father, Christian Welty, think of all these stories of her father my mother told? I never knew. My father was Ned Andrews's very opposite, all that was stable, reticent, self-contained, willing to be patient if need be, and, in everything he said, factual. Before the birth of my brothers, when my mother and I went up on the train alone, my father would come at the end of our visit to shepherd us home.

I was not too much of a baby to notice and remember how different it was when my father arrived on the scene. A difference came over whatever we were doing, like a change in the wind.

The fact was, my mother and I were the only ones really dying to see him come. Of course he was older than they, the brothers—six years older than Chessie, their older sister—and he was a Yankee, but I came to realize later what must have been the real reason for the polite distance they put into their welcome: ever since he'd first come courting, they'd known he was only here to take their sister away from them.

It was in this house they saw their sister married. Mother's brothers never in my memory called my father other than "Mr. Welty," and certainly they didn't then, on the wedding day; Moses, the youngest, went out and "cried on the ground." The newlyweds left on the train for the World's Fair and Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition that had opened (a year late) in St. Louis. It was October 1904. They would then go on to Jackson, Mississippi, and the future. My mother thought it was ill-becoming to brag about your courage; the nearest she came was to say, "Yes, I expect I was pretty venturesome."

It must have seemed to her family behind her that she had been cut off from them forever. They never really got over her absence from home.

I don't think she ever really got over it, either. I think that she could listen sometimes and hear the mountain's voice—the delayed echo of the unseen and distant old man—"just an old hermit," said Grandma—chopping wood with his ax and calling on God in alternation, in answering blows; the prattling of the Queen's Shoals in Elk River somewhere below, equally out of sight, which I believed I could hear from Grandma's front-yard rocking chair, though I was told that I must be listening to something else; the loss and recovery of traveling sound, the carrying of the voice that called as if on long threads the hand could hold to, so I would keep asking who that was, who was still out of sight but calling in the mountains as he neared us, as we brought him near.

I think when my mother came to Jackson, she brought West Virginia with her. Of course, I brought some of it with me too.

For as long as she lived, letters went back and forth every day between my grandmother and my mother. Grandma always had to concern herself with her letters getting carried down the mountain to the courthouse to make the train.

Dear Chessie,

I wrote to you last night but did not give it to Gus this morning as I thought Carl would be sure to go to the C.H. and as he had letters of his own to mail would not be likely to forget. He had his overcoat on to go before dinner but I told him that dinner was ready and after we had started to eat Moses came in and said the dog was after a fox and all of the boys left as soon as they were through dinner and here is my letter and I hear the train now so it will not go. It stopped raining last night and today it has been snowing part of the time and blowing nearly all of the time and so dark and gloomy looking that I only sit by the fire. I wish you had a half dozen of my chickens. I killed three last week for the boys to take to school. I do wish I could step in a while and see you and as I cannot I think I will take a nap. With lots of love from Mother

And:

Carl is writing letters to different ones that he thinks might come to school, Gus and Moses are playing on their banjoes as Eudora would say, I do not know what John is doing, he is in the other room.

Say, do you believe that two pigeons could be sent from here to Eudora say in April or do you think they could not go without someone being along to take care of them. She would like them for they would fly all around her and eat out of her hand if she would let them. We are all well and do hope you are all well, with lots of love from Mother, and kiss Baby

And one on a November 4:

My dear child,

I received no letter yesterday but had expected to start one to you this morning but failed. I had thought I would walk to the C.H. and started to get ready. It is a beautiful day overhead, you cannot see a cloud and yet the wind is fearful. I have nearly finished my looming [?], scrubbed the dining room and kitchen, picked up three or four bushels of walnuts, I washed yesterday and found two hen's nests with sixteen eggs in them. I told Gus I had saved 75 or a dollar and made a quarter, as eggs are 25t a dozen The boys have started to school and I believe they will learn, they both seem pleased with their Teacher. Maggie Keeney's fourth sister is teaching the lower room. Maggie Cora and Mattie as you may know are married, that leaves Hester and this one to teach. Gus said last night that one of Clay's teachers died yesterday, a bright young man. I wish I was able to do with my hands as fast as I find jobs to do, and maybe I could set things straight but I cannot do that. I am lonely enough but if you and baby could walk in sometime to see Grandma I would do all right but I hope both and all three of you keep well, with a heart full of love from Mother

This is a letter she wrote to me:

My dear Eudora Alice,

I do wish I could go on the choo choo train and see you and be at your little party, I would bring you two pretty little pigeons, for I know both you and your little friends would enjoy having them, but as I cannot go nor send the little pigeons, I am going to the Court House this morning and see if I can send you a little cup of sugar you can eat and think of Grandma. I hope you will have a nice time and be well. With lots of love from Grandma

P.S. Tell your Ma I will write to her next time.

Such were my mother's component parts.

Grandma had thought my agitation and fear of her overfamiliar pigeons was love. I can see now, from my own words, that perhaps she was right.

That summer, lying in the long grass with my head against the back of a saddle, with the zenith above me and the drop of distance below, I listened to the mountain silence until I could hear as far into it as the faint clink of a cowbell. In the mountains what might be out of sight had never really gone away. Like the mountain, that distant bell would always be there, reminding.

It took the mountaintop, it seems to me now, to give me the sensation of indepen dence. It was as if I'd discov ered something I'd never tasted before in my short life.

And indeed I had. I must have associated it with the taste of the water that came out of the well, accompanied with the ring of that long metal sleeve against the sides of the living mountain, as from deep down it was wound up to view brimming and streaming long drops behind it like bright stars on a ribbon. It thrilled me to drink from the common dipper. The coldness, the far, unseen, unheard springs of what was in my mouth now, the iron strength of its flavor that drew my cheeks in, its fernlaced smell, all said mountain mountain mountain as I swallowed. Every swallow was making me a part of being here, sealing me in place, with my bare feet planted on the mountain and sprinkled with my rapturous spills. What I felt I'd come here to do was something on my own.

My mother adored her brothers, "the boys," and she was their heart. One day she and the boys, taking me along, were dawdling down the mountain path and talking family together. I thought I'd take off on a superior track I saw for myself, and the next moment I was flying down it, straight down, then falling, rolling and tumbling, gathering dust and leaves in my clothes and hair, and I could hear a long rip coming in my skirt without being able to stop until some bush caught hold of me. I got to my feet and looked back up. It wasn't far, but my mother and the boys might have been standing over the rim of the moon: they were laughing at me, my mother along with the boys, helplessly laughing. One of my uncles dropped down to me and carried me up again. I went back with them, riding on his shoulders. The boys—though not my mother now— were still teasing, and I was aloft up there, hanging my head or holding it up—I can't be sure now.

"Well, now Girlie's learned what a log chute is," said Uncle Carl, putting me down in front of Grandma as if to let her in on the family joke. Her gesture then was the final other thing I remembered from being here before: with her forefinger she pushed my hair behind my ears and bared my face to hers. She looked seriously right into my eyes. There together, we both knew some identical true thing: Had we come right to the fact of our both being named Eudora?

"Run take that little dress of yours off, and Grandma'll sew up the hole in it right quick," she said. She looked from me to my mother and back; I learned on our trip what that look meant: it was matching family faces.

The Cardens had been in West Virginia for a while—I believe were there before West Virginia was a state. Eudora Carden's own mother had been Eudora Ayres, of an Orange County, Virginia, family, the daughter of a Huguenot mother and an English father. He was a planter, fairly well-to-do. Eudora Ayres married another young Virginian, William Carden, who was poor and called a "dreamer"; and when these two innocents went to start life in the wild mountainous country, in the unknown part that had separated itself from Virginia, among his possessions he brought his leather-covered Latin dictionary and grammar and she brought her father's wedding present of five slaves. The dictionary was forever kept in the tiny farmhouse and the slaves were let go. One of the stark facts of their lives in Enon is that during the Civil War GreatGrandfather Carden was taken prisoner and incarcerated in Ohio on suspicion of being, as a Virginian, a Confederate sympathizer, and lost his eyesight in confinement.

Their son, Mother's Grandpa Carden, was the Baptist preacher. Enonnear-Gilboa was the name of his church—taken from the Bible, of course; Gilboa, on the mountain as in the Bible, was the older church it was near to. Enon was where Eudora Carden and four brothers were born, and where later the Andrews children spent a great deal of their time. Grandpa Carden was an enormously strict and vigorous-minded old man.

When his first wife died, leaving him a young man with little children, Grandpa did what so many did then: he sent back to Virginia for her sister. Then, after an interval, he married her. My mother, at a young and knowing age, once praised her to her face for her unselfishness in coming from Virginia and marrying Grandpa for the sake of his motherless children, and the old lady replied tartly, "Who says that's why I married him?"

My mother and the boys spent a lot of time visiting Grandpa and Grandma Carden. This good old man liked to retire to the barn to say his bedtime prayers where he could thunder them up as he pleased, to the rafters. Mother's little brothers used to delight in hiding in the hay, where they could listen to Grandpa pray, and he on his side would be sure to get all their names in when he was asking for forgiveness; he'd beg the Lord to be patient with them, whatever had been their sinful ways, and lead them into righteousness before it was too late.

Sometimes at our house, when my mother read the Bible in her rocking chair by the fire, as she liked to do, I saw her lips twitch. "I'm just so strongly reminded of Grandpa Carden when I come to Romans," she'd say.

She'd been pretty lively toward Grandpa in her own youth. "I don't agree with Saint Paul," she'd told him once; it was in connection with the rule of wearing a hat to church.

In our picture of Grandpa Carden, his long beard and side whiskers are pure white, and seem to be stirred by some mountain wind. His large black hat is resting upside down on his knee as he sits on a straight-back bench. His right hand is holding, straight-upand-down and thin as a rod, his staff; it looks four or five feet tall. The photograph is inscribed across the back in a strict hand, "To Chessie, if she will have it."

Theirs had been early days. I tend to think that it had been Ned Andrews, all the same, who saw himself as the pioneer in West Virginia; he was the lone romantic in this story. He might have delighted in imagining the figure he'd cut to them back in Tidewater, Virginia. (They did wonder at him, which, I think, is to say the least. I grew to know the Virginia Andrewses, his remarkable mother and his sisters, who, when they knew of his death, joined the connections all around; with all Ned's family, and with Chessie in particular, close ties formed then were never to be lost.)

In the eyes of all their devoted children, and in every word I ever heard my mother and the boys say, it appeared that neither of their parents could have ever done conscious wrong or made an irretrievable mistake in their lives.

When their mother died, the boys were to come down from the mountain. They were to marry and make their own lives—except for John, who died of pneumonia after enlisting in the army in 1918—in teaching, banking, civic or business affairs below. Carl was to become mayor of Charleston. They were never to let go of the home place. It is still kept up as a family retreat, a camp for hunting and fishing; Andrewses still roam the mountains.

It seems likely to me now that the very element in my character that took possession of me there on top of the mountain, the fierce independence that was suddenly mine, to remain inside me no matter how it scared me when I tumbled, was an inheritance. Indeed it was my chief inheritance from my mother, who was braver. Yet, while she knew that independent spirit so well, it was what she so agonizingly tried to protect me from, in effect to warn me against. It was what we shared, it made the strongest bond between us and the strongest tension. To grow up is to fight for it, to grow old is to lose it after having possessed it. For her, too, it was most deeply connected to the mountains.

When she was old, widowed, ill, and nearly blind, my mother one day announced to me she would be very glad to have the piano back in our house. It was the Steinway upright she had bought for me when I was nine, so far beyond her means, and had paid for herself out of the housekeeping money, which she added to by buying a Jersey cow, milking her, and selling part of the milk to the neighbors on our street, in quart bottles which I delivered on my bicycle. While I sat on the piano stool practicing my scales, I imagined my mother sitting on her stool in the cowshed, her fingers just as rhythmically pulling the teats of Daisy.

Two of her children had played this piano, I practicing my lessons and my brother Edward all along playing better by ear. When her granddaughters came along, the piano was sent to their house to have their lessons on. Now, all those years later, Mother wanted it under her roof again. Right now! It was brought and, the same day, tuned. She asked me to go directly to it and play for her "The West Virginia Hills."

I sat down and remembered how it went, and as I played I heard her singing it—singing it to herself, just as she used to while washing the dishes after supper:

0 the West Virginia hills!

How my heart with rapture thrills. . .

0 the hills! Beautiful hills!...

This one moment seemed to satisfy her. Once from her wheelchair afterwards, she tried to pick it out herself, laying her finger slowly down on keys she couldn't really see. "A mountaineer," she announced to me proudly, as though she had never told me this before and now I had better remember it, "always will be free.'1''

Oh, yes, we're in the North now," said my mother after we'd crossed the state line from West Virginia into Ohio. "The barns are all bigger than the houses. They care more about the horses and cows than they do about..." She forbore to say.

The farm my father grew up on, where Grandpa Welty and Grandma lived, was in southern Ohio in the rolling hills of Hocking County, near the small town of Logan. It was one of the neat, narrow-porched, two-story farmhouses, painted white, of the Pennsylvania-German country. Across its front grew feathery cosmos and barrel-sized peony bushes with stripy heavy-scented blooms pushing out of the leaves. There was a springhouse to one side, down a little walk only one brick wide, and an old apple orchard in front, the barn and the pasture and fields of corn and wheat behind. There were sounds from the barn, and you could hear the crows, but everything else alive was still.

In the house it was solid stillness, it seemed to me, at almost any hour, all day, except for dinnertime. Whoever was in the house seemed to remain invisible, but this was because they were all busy. I think in retrospect that my father had set our visit in time to help with the harvest, and certainly he was very busy outside all day. He let my brother Edward go with him.

My mother, in the way she had, never put aside her first impression of Grandpa Welty. She was hurt when he met the train in the spring wagon, not the buggy. All the way home to the farm, he never started a conversation with her. "But that was his custom," years later she explained to me. "He never brought out much to say till I was ready to go. Then on my last day, on the long ride to the station, he never stopped talking at all. He talked up one blue streak." They took to each other enormously.

Throughout our visit, as long as the daylight held, he was out stirring about the barn or moving through the fields. He was a quiet, gentle man, with a flourishing mustache, with not much to say to the women and children in his house; when he did sit down, it would be in his wooden platform swing outside, usually with his pipe and holding one of the farm kittens on his knee. Now and then he held me there, and then I got to hold the kitten.

My grandmother Welty was my father's stepmother. My mother would remark, "There's one thing I will have to say about Mother Welty: she makes the best bread I ever put in my mouth." It really is the only thing I can remember she ever said about Grandma Welty, though she did feel often compelled to repeat it, and never said anything different after the old lady died.

Grandma Welty, with each work day in the week set firmly aside for a single task, was not very expectant of conversation either. Of course I remember Friday best—baking day. Her pies, enough for a week, were set to cool when done on the kitchen windowsills, side by side like so many cheeky faces telling us "One at a time!"

Like the hub that would make the dinner table go round, if it ever could start, was a tulip-shaped glass in the center in which the bright-polished teaspoons, all the largest family could ever need, stood facing in with their backs turned. I don't believe this spoon holder ever left the table. Even in the dark dining room at midnight in the sleeping house, it would stand ready there. The smell of all those loaves of bread and the row of pies didn't easily go away, either. And in the parlor where the blinds were drawn, the smell of being unvisited would pervade, pervade, pervade.

Compared with the Andrews clan, the Welty family, at the time of the first visit I remember, was very scarce in the way of uncles and cousins and kin of an older generation. Grandpa, Jefferson Welty, had been the youngest of thirteen children, but he is the only one I ever saw; his parents were Christian and Salome Welty, early settlers in Marion Township, Hocking County. The Weltys were originally German Swiss; the first ones to come to this country, back before the Revolutionary War here, were three brothers, and the whole family is descended from them, I understand—it seems to hark back to German fairytale tradition.

My father is not the one who told me all this: he never hap-

pened to tell us a single family story; could it have been because he'd heard so many of the Andrews stories?

I think it was rather because, as he said, he had no interest in ancient history—only the future, he said, should count. At the same time, he was exceedingly devoted to his father, went to see him whenever he could, and wrote to him regularly from his desk at home; I grew up familiar with seeing the long envelopes being addressed in my father's clear, careful hand: Jefferson Welty, Esquire. It was the only use my father made of the word; he saved it for his father. I took "Esquire" for a term of reverence, and I think it stood for that with him; we were always aware that Daddy loved him.

An English Welti, who spelled his name thus with an i, wrote to me once from Kent, in curiosity, after an early book of mine had appeared over there; he asked me about my name. My father, who had never told us anything, had died, and this was before my mother set herself, as she did later, to looking into records. Mr. Welti knew about the whole throng of them, from medieval times on, and the three brothers who set forth to the New World from German Switzerland and settled from Virginia westward over Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana before the Revolutionary War. "I expect you know," wrote the British Mr. Welti, "that one unfortunate Welty fell at Saratoga."

In Grandpa's and Grandma's parlor stood the organ, which, my mother had whispered to me, they preferred not to hear played. I tiptoed around it as if it were asleep. There were steep, uphill pedals; the flowered carpet continued right on up them as if they were part of the floor. When opened, the organ gave off a smell sharp as an exclamation, as if opening it were a mistake in company manners, which I already knew. I chilled my finger by touching a key. The key did not yield. The whole keyboard withstood me as if it had been a kitchen table; I suppose the organ had to be pumped.

But either I had been told so, or I got the feeling there and then that this organ had belonged to my father's real mother, who had died when he was a little boy. But when I was named Eudora for my Andrews grandmother, I had been named for this grandmother too. Alice was my middle name. She had been called Allie. Too late, after I was already christened, it came out that Allie stood for not Alice but Almira. Her name had been remembered wrong. I imagined what that would have done to her. It seemed to me to have made her an orphan, after she had already had to die.

Barefooted on the slick brick walk, I rushed to where I could breathe in the cool breath from the interior of the springhouse. On a cold bubbling spring, covered dishes and crocks and pitchers of butter and milk and so on floated in a circle in the mild whirlpool, like the horses on a merrygo-round in the water that smelled of the mint that grew close by.

Or I ran to the barn where all you touched was warm. Grandpa's barn was bigger than his house. The doors had to be rolled back. It had a plank floor like a bridge that came to an end at the wall and another door. The barn was

fuller than the house of things, barrels and boxes and wagons and troughs, and with all of the things they held. With all Grandpa kept there, there was more to see, more to smell, more to climb on. At times when the animals were down in the pasture, I could hear the dry seed corn running through my fingers in the waiting stillness. When the animals had been led inside, now and then a horse's head would appear looking over the door of his stall. Then I played nearby, to give the head a chance to speak to me, like Falada, the white horse's head nailed above the gate in the fairy tale that says to the goose girl driving her geese, "Princess, Princess, passing by, / Alas, alas, if thy mother knew it, / Sadly, sadly her heart would rue it." Up in the loft, going wild in the hay, I skinned through the hole through which it was tossed to the trough below, and the trough caught me neatly. My brother Edward, not missing a hop in the hay, didn't even know I'd gone.

There was an old buggy being used for hens to nest in, standing in the shadows of the barn. The shiny black buggy next to it, with a fringe on top, was the one in which Grandpa drove us to church. He allowed me to stand between his knees and hold the reins, even though I could not see over the horse's too busy tail where we were going. But standing up on the back seat, I could see, squinting through the peephole window at the back, where our narrow wheels on a rainy Sunday sliced the road to chocolate ribbons. I got to hear Grandpa's voice on Sunday more than in all the rest of the week, because he sang in the choir; indeed, Grandpa led the choir.

A t the end of the day at Grandpa's house, there wasn't much talking and no tales were told, even for the first time. Sometimes we all sat listening to a music box play.

There was a rack pulled out from inside the music box; we could see it holding shining metal disks as large as silver waiters, with teeth around the edges, and pierced with tiny holes in the shape of triangles or stars, like the tissue-paper patterns by which my mother cut out cloth for my dresses. When the disks began to turn, taking hold by their little teeth, a strange, chimelike music came about.

Its sounds had no kinship with those of "His Master's Voice'' that we could listen to at home. They were thin and metallic, not exactly keeping to time—rather as if the spoons in the spoonholder had started a quiet fretting among themselves. Whatever song it was was slow and halting and remote, as if the music box were playing something I knew as well as "Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms" but did not intend me to recognize it. It seemed to be reaching the parlor from far away. It might even have been the sound going through the rooms and up and down the stairs of our house in Jackson at night while all of us were here in Ohio, too far from home even to hear the clock striking from the downstairs hall. While we listened, there at the open window, the moonflowers opened little by little, and the song continued like a wire spring allowing itself slowly, slowly to uncoil, then just stopped trying. Music and moonflower might have been geared to move together.

Then, in my father's grown-up presence, I could not imagine him as a child in this house, the sober way he looked in the little daguerreotype, motherless in his fair bangs and heavy little shoes, sitting on one foot. Now I look back, or listen back, in the same desire to imagine, and it seems possible that the sound of that sparse music, so faint and unearthly to my childhood ears, was the sound he'd had to speak to him in all that country silence among so many elders where he was the only child. To me it was a sound of unspeakable loneliness that I did not know how to run away from. I was there in its company, watching the moonflower open.

I never saw until after he was dead a small keepsake book given to my father in his early childhood. On one page was a message of one sentence written to him by his mother on April 15, 1886. The date is the day of her death. "My dearest Webbie: I want you to be a good boy and to meet me in heaven. Your loving Mother." Webb was his middle name—her maiden name. She always called him by it. He was seven years old, her only child.

He had other messages in his little book to keep and read over to himself. "May your life, though short, be pleasant / As a warm and melting day" is from "Dr. Armstong," and as it follows his mother's message may have been entered on the same day. Another entry reads: "Dear Webbie, If God send thee a cross, take it up willingly and follow Him. If it be light, slight it not. If it be heavy, murmur not. After the cross is the crown. Your aunt, Nina Welty." This is dated earlier—he was then three years old. The cover of the little book is red and embossed with baby ducklings falling out of a basket entwined with morning glories. It is very rubbed and worn. It had been given him to keep and he had kept it; he had brought it among his possessions to Mississippi when he married; my mother had put it away.

In the farmhouse, the staircase was not in sight until evening prayers were over—it was time to go to bed then, and a door in the kitchen wall was opened and there were the stairs, as if kept put away in a closet. They went up like a ladder, steep and narrow, that we climbed on the way to bed. Step by step became visible as I reached it, by the climbing yellow light of the oil lamp that Grandpa himself carried behind me.

Back on Congress Street, when my father unlocked the door of our closed-up, waiting house, I rushed ahead into the airless hall and stormed up the stairs, pounding the carpet of each step with both hands ahead of me, and putting my face right down into the cloud of the dear dust of our long absence. I was welcoming ourselves back. Doing likewise, more methodically, my father was going from room to room restarting all the clocks.

I think now, in looking back on these summer trips—this one and a number later, made in the car and on the train—that another element in them must have been influencing my mind. The trips were wholes unto themselves. They were stories. Not only in form, but in their taking on direction, movement, development, change. They changed something in my life: each trip made its particular revelation, though I could not have found words for it. But with the passage of time, I could look back on them and see them bringing me news, discoveries, premonitions, promises—I still can; they still do. When I did begin to write, the short story was a shape that had already formed itself and stood waiting in the back of my mind.

Nor is it surprising to me that when I made my first attempt at a novel, I entered its world—that of the mysterious Yazoo-Mississippi Delta—as a child riding there on a train: "From the warm window sill the endless fields glowed like a hearth in firelight, and Laura, looking out, leaning on her elbows with her head between her hands, felt what an arriver in a land feels—that slow hard pounding in the breast."

The events in our lives happen in a sequence in time, but in their significance to ourselves they find their own order, a timetable not necessarily— perhaps not possibly—chronological. The time as we know it subjectively is often the chronology that stories and novels follow: it is the continuous thread of revelation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now