Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE WILL TO BEAUTY

FROM PLATO TO PLAYBOY, THE BODY BEAUTIFUL HAS BEEN CHANGING WITH EVERY CULTURAL BREEZE...BUT IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICA IT HAS BECOME FROZEN, AND SUDDENLY MILLIONS OF US ARE SCRAMBLING TO TAILOR OUR OWN BODIES TO THE CURRENT IDEAL...ON THE FOLLOWING PAGES, THE SURGE OF NUDE IMAGERY—AND WHAT IT'S DOING TO US TODAY...

Edie Sedgwick

R. Crumb fantasy

Marlyn Monroe

Carole Lombard

Jayne Mansfield

Sophia Loren

Erotic postcard

Lisa Lyon

"The Toilet"

Lisa Lyon

Jean Harlow

Christie Brinkley

Jayne Mansfield

Barbie doll

Durer's Witches

Edwardian photo

Collage by Yolanda Cuomo

Marilyn

Raquel Welch

Veruschka

Post-op Edie

Theda Bara, Cleopatra

Genuine Turkish Delight"

Ornamental scarring

Jayne

Fonda as Barbarella

Sophia

R. Crumb's advice

Anita Ekberg

Joan Crawford

Carole Lombard

Burmese beauties

Bottle beautiful

Marilyn in Playboy

Jane Fonda

Sweating beauty

Stripper Iris Adrian

Mae West

French erotic postcard

Edwardian pinup

Egon Schiele nude

Nastassia

Dretrich transfigured

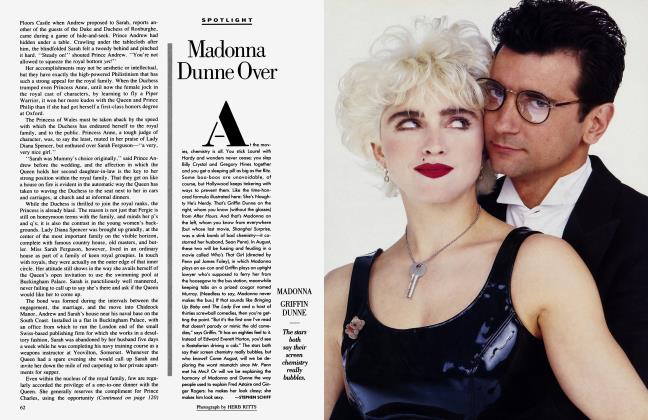

STEPHEN SCHIFF

The movie actress Mariel Hemingway is a big, friendly kid with a squeaky little voice and a cheerleader's giggle. But in recent photographs she looks eerily beautiful—a machine-tooled Venus revealing her chest for the camera, the look on her face a provocative blend of defiance and Hollywood coyness. The body she's showing off is not all hers, of course. She acquired breast implants before undertaking her role as the doomed centerfold, Dorothy Stratten, in Bob Fosse's movie Star 80. And she looks every inch the intrepid pioneer, fiercely proud of the miracle science has wrought, yet not quite secure about taking the credit for it. One is reminded of other actors who have gone to heroic lengths to change their bodies for a role, of Robert De Niro ballooning by sixty pounds to play Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, of Michael Caine cultivating a belly for Deathtrap and Educating Rita, of John Travolta trading in his own body for a copy of Sylvester Stallone's for Staying Alive. But Mariel Hemingway is different. Her body has been permanently altered; she will carry her renovated balcony with her long after her performance as Dorothy Stratten has ended and her lifelong performance as Mariel Hemingway has resumed.

Two or three decades ago, an actress might have changed her name to be in a movie, might have colored her hair and lied about her age; she might have even purchased a more felicitous nose. Sexual imagery was a dreamworld. It was all done with backlighting on the coiffure, perfect makeup, the right padding in the right places. It was all done with mirrors. But no longer. The screen actress has nowhere to hide when there are nude scenes to be shot—unless another, more conventionally shapely performer is hired as a stand-in. Since 1965, when a spot of nakedness in The Pawnbroker marked the welcome demise of the Hollywood production code, American movies have found themselves proliferating images of the nude—particularly the female nude—at a rate that has taken on the proportions of a stampede. And this has changed a certain subtle balance in the way we view the world. One is now likely to see more nudity on the screen than in life. And while that could be said of a great many things—one is also likely to see more murders, more rapes, more monsters, more chandeliers —the barrage of nudes has a very different impact. Although chandeliers and even monsters have their own offscreen reality, we perceive them as existing only within the borders of the screen. The reality of a naked body in a movie is deeper than that, and more encompassing; it refers not only to what's going on in the film but also to that other reality offscreen, behind the film—and, in a very insistent way, to ourselves. It is the thing we most share with the world of the movie we're watching.

That's why explicit scenes of sexual violence, even the ones that intend to provoke horror, are titillating— especially when they feature beautiful actresses. No matter what mayhem we're meant to be recoiling from, we may feel aroused in spite of ourselves, because we know the horror is staged; the only real thing on the screen is a comely naked body. When the costume falls away, so does the last vestige of fiction. That body is no longer a character's, it's the actress's own. The power of nude imagery in the movies is extraordinary, and a great deal of it has paraded by since the screen surrendered its prudishness. But the American film industry, not much given to risk taking, spurned the opportunity to talk seriously about sex and the bodies that perform it. Very quickly, the movies set out to make screen nudity marketable, uniform, and safe.

Every era has its conventional notion of what is erotically attractive. Since the movies could no longer merely suggest the sexy body, they had to invent it; they had to arrive at a body whose eroticism the public could agree on. This was not, of course, a conscious and concerted effort, and it was made simpler by the fact that the model female body had already been established. In postwar American culture she has been more or less an hourglass, or rather an old-fashioned Coke bottle—or, to use the formulation that locker room satyrs have inherited from the garment trade, 36-24-36.

Writers on fashion enjoy fuming over how quickly desirable body styles change, sputtering that where once breasts were in, now bottoms hold sway, and vice versa. By their lights, photography has only made matters worse, tying the body public closer to new fashions and to the models who prance about in them. Actually, the stream of nude imagery has created something quite unprecedented—a separate standard of fashion that governs the unclothed body alone. Even though styles in female dress and female models have changed over the past three decades—consider the anorexic boniness of Edie Sedgwick and Twiggy, the svelteness of Lauren Hutton, the ambiguity of Grace Jones and Annie Lennox—fashions in female nudity have remained frozen. Perhaps that's because a market directed at females determines fashion in dress, and a market directed at males determines fashion in undress; it's the difference in taste between people like Jackie Onassis and Calvin Klein and people like Howard Hughes and Hugh Hefner. The underground cartoonist R. Crumb likes to depict his male dilettantes and put-on artists loafing in a dreamy oblivion, and the dream scudding above them is of a female torso, headless and legless, as rigid and plastic as though it had been stamped into their brains by a machine. I think most American men carry that torso around in their brains. It has taken on the force of an icon, divorced from the head that rides atop it, the clothes that camouflage it, and the soul that flutters within.

When the body comes to be viewed as an icon, our relationship with it changes. It turns into a symbol, like a word or crucifix—and, like other symbols, it loses its privacy. It is no longer just my organism, the thing that keeps me alive and allows me sensory communion with the world. It is also a way of communicating, a bit of terminology. Of course, communication is possible only when we all agree on a symbol's meaning, and so for the body to become the relatively effective symbol it now is, it has had to be standardized. A substantial number of Americans agree on the meaning of the nude 36-24-36 body. What they think of a bony nude or an oddly formed one depends on all sorts of personal quirks and conditions. Physical imperfection is tricky, hard to "read"—ambiguous.

For reasons that remain mysterious, societies embrace some symbols and snub others. The slang word "ripoff," for instance, seems to have attained a permanence that "groovy" never managed; neckties are forever, knickers aren't. A symbol becomes permanent when we develop a way of making it ours. And so it is that we've developed ways of acquiring the standardized nude body. Two ways, to be exact: cosmetic surgery and the health club culture. Now, for the first time in history, Americans can nonchalantly change their bodies to match those on the screen. For less than the price of a used car, any woman can have the operation Mariel Hemingway had. For half that, she can enroll in a health spa for a year, where "scientific" exercise programs can tell her exactly what to do to make this muscle bulge and that bulge vanish. In a world of such dazzling physiological possibility, the stylized body comes to seem an article of apparel.

You can put it on or take it off. And it can now bear messages, the way clothes always have. A woman who reduces her breasts surgically is conveying a message of (clothed) chicness; a woman who enlarges them is conveying (nude) eroticism; a woman who has her face lifted is trying to change her position in the social scheme, just as a fifty-year-old businessman is when he wears cut-offs and a Def Leppard T-shirt. For the latter-day version of Veblen's self-improving bourgeoise, the body turns into an article of Conspicuous Consumption. Her new physique tells the world that she can afford a new physique.

Of course, cultures from the beginning of time have undergone all manner of suffering to achieve parochial ideals of beauty. The Japanese and the Northwest Coast Indians lavishly tattooed themselves; African tribesmen slice scars into their skins; the Chinese used to bind feet; the Melanesians and the tribal Americans used to bind heads. But all this strikes me as fundamentally different from the contemporary American's pursuit of beauty. Ritual self-mutilation typically derives from the notion that the naked body is not in itself beautiful and must be decorated to become so. As a Dogon named Ogotemmeli told the anthropologist Marcel Griaule, "From a very beautiful woman without ornament, men turn away. To be naked is to be speechless." Not so in America, where to be naked is to spout a mouthful. Here, the body itself becomes an ornament. What we do to it isn't decoration, it's repair work; it's fixing what we think "nature has forgotten." To us, the unadorned body is plenty beautiful, so long as it's the right body. Mariel Hemingway's new breasts proclaim the rightness of her body; they're like the alligator on the Izod shirt. And a man admiring a woman's body, whether or not he's conscious of it, can now be said to be admiring her taste.

"A MAN ADMIRING A WOMAN'S BODY, WHETHER OR NOT HE'S CONSCIOUS OF IT, CAN NOW BE SAID TO BE ADMIRING HER TASTE"

At a much slower—but accelerating—rate, the male body too is becoming iconic. That, in fact, may be one of the ways in which the feminist movement has backfired. Released from the pedestal and the kitchen, women have encountered an array of confounding new roles, and most of the available role models have been men. Hence women in the job market wear dull imitations of men's (already dull) business suits, and women in the new sexual arena patronize male strip shows modeled on female strip shows; the ads that show Jim Palmer brandishing briefs ape the time-honored tradition of the lingerie ad. Stranger still, the woman who chooses to become a body builder develops a physique that copies the male body builder's. Photos of Lisa Lyon, for instance, have the surreal aura of a fetishistic collage—a sinewy male body with female parts pasted on it.

The laboratory where the new sexual tinkering transpires seems to be the health club culture. Last summer, in a self-consciously trendy Rolling Stone article

(soon to be a major motion picture), Aaron Latham announced, "Coed health clubs are the singles' bars of the Eighties." He quotes one of the denizens of these new mating dens: "One reason it's a good place to meet people is because of the way everybody dresses. What you see is what you get." And this teeming miasma of Nikes and Danskins has begotten the hottest thing in fashion, sweats— exercise clothes designed to be worn on the street, to restaurants, to parties—clothes that, without being in themselves alluring, nevertheless advertise membership in the new army of machine-tooled physiques. The clothed figure has always tried to suggest a finished product. Clothes were an acceptable lie because they made the body—which had complex imperfections everyone acknowledged—look better than it could possibly be. But sweats perform almost the opposite function. Deliberately bland and unassuming, they convey process, not product. They say, "The body underneath doesn't need clothes, because it is perfect, and it is maintaining its perfection." Sweats are like medals on a military uniform; they're accessories that announce the accomplishments of the wearer. And of course the accomplishment and the uniform are both the body itself.

Ever so gingerly, his tongue darting in and out of his cheek, Latham hints at the wonderful Americanness, the Emersonian self-reliance inherent in the health club culture. He insists that Emerson's "presence is felt symbolically in health clubs across the land because they represent a return to his values." Articles elsewhere have blithely backed this view, but of course it's nonsense. Emerson's "Self-Reliance" was a goad to greater originality, not to more effective imitation of a conventional ideal. "I hope in these days we have heard the last of conformity and consistency," he bellowed; a nation of look-alike bodies in look-alike leotards would have horrified him. In fact, if the obsession with the body resembles any other cultural strain, it may be the aesthetics of fascism. The "no pain, no gain" body-building creed has accumulated a spooky, cultish aura; iron pumpers can now buy T-shirts that brag HURTS SO GOOD. Like fascism, and like the sadomasochism that is its erotic kin, the body culture is about fantasies of power and pain, domination and submission.

And yet isn't this world of spas and surgeons relatively harmless? After all, we're talking about the will to beauty, not the will to power; all those operating tables and Nautilus machines may look like the trappings of Nazi medical experiments, but they are hardly spawning a new Reich. For all their assertions that they have "an edge," that they are members of a "special group" (as one muscle-bound banker told Time magazine), the health clubbers are not bent on political power. They are not a party; they share no ideology. And is their regimen really very different from the one that spurs on the great athlete or dancer? Perhaps not. But when the athlete works out, he's reaching toward a body that's united with his vision. It is when the body is carved into an emblem not of individual vision but of a bland, commonly acknowledged beauty that we grow alienated from it. The parts of the body, which are ours, which function biologically as glands and organs, become the Other. They belong to what's Out There. And we begin to evaluate them as we evaluate almost everything else Out There—as commodities, products, aids to our social and economic progress. The body, our material emissary to the world, joins the other side. It becomes a turncoat, a metaphysical double agent.

The will to beauty is part of a larger syndrome, peculiar to this culture, that takes the form of a tyranny—the tyranny of the image. Other cultures have suffered under political tyrannies, which bolster their rule with imagery—with swastikas or little red books or boymeets-tractor movies. But we have allowed imagery itself to tyrannize us, to dictate what we think and do and feel, and we have allowed it in the very face of our political freedoms. I think we're all at least subliminally aware of the tyranny of the image. And if it restricts the way we make our decisions, the way we understand the world and our place in it, well, that is perhaps its charm: it numbs the urgency of self-determination. The will to beauty is a sort of convulsion, a spasmodic contraction that regulates sexual desires and choices in a society that may be more frightened of them than it realizes. Real sexual freedom would mean the freedom to adopt individual sensual tastes, and that is something we have never had in this country, even in the most liberal of eras. It is also something we could have, anytime enough of us wanted it. We are very far from being a society that lets its members love whom they choose, and how. And so the body culture may be viewed as a self-imposed discipline, a barrier, a Maginot Line erected by those who imagine themselves the hippest and the freest, against the scary erotic temptations that the last two decades have made available. The will to beauty is sexual repression disguised as hedonism—a new repression for a "liberated" age.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now