Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

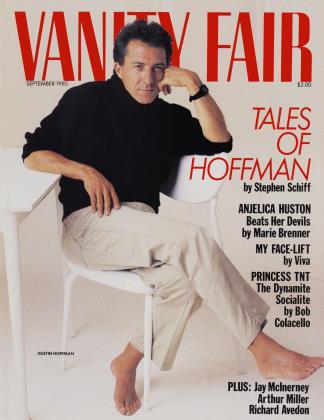

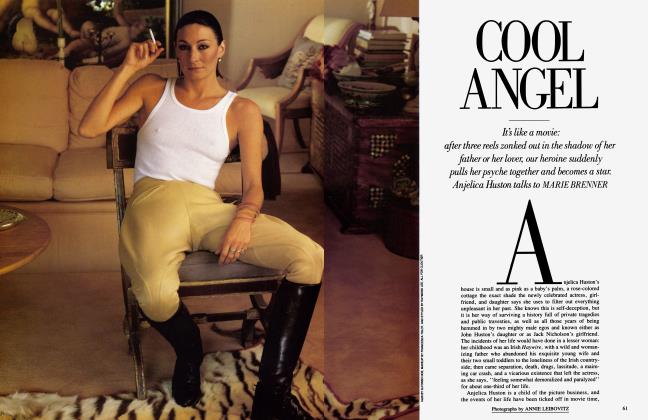

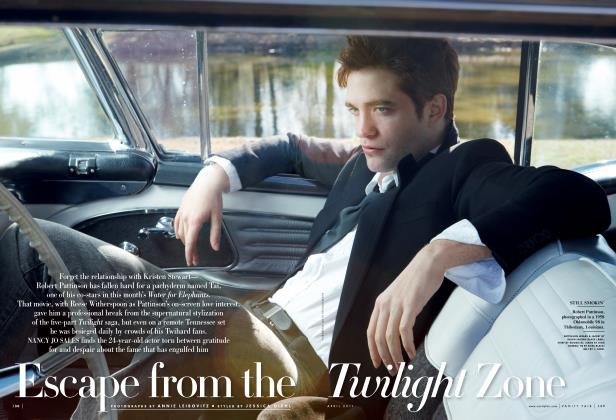

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDustin Hoffman hits the screen again this month. The small screen, that is, in CBS's version of his Broadway smash, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Here, STEPHEN SCHIFF explores the legendarily "difficult" Dustin's technique— and how it consistently takes him to the top of the acting class. Following that, Hoffman and Miller talk about the production

September 1985 Stephen Schiff Annie LeibovitzDustin Hoffman hits the screen again this month. The small screen, that is, in CBS's version of his Broadway smash, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Here, STEPHEN SCHIFF explores the legendarily "difficult" Dustin's technique— and how it consistently takes him to the top of the acting class. Following that, Hoffman and Miller talk about the production

September 1985 Stephen Schiff Annie LeibovitzHe stands a hair over five feet six, and his nose is a honker; his voice sounds like a chicken underwater. When he shuffles into a room the stooped shoulders and thrust neck put one in mind of a sleepy gnu. But let this unprepossessing creature decide to make a movie and studio heads will spring from their swivel chairs, producers will sweat and pray into their cellular phones. If Dustin Hoffman wants to act in your movie or play, you know two things: that you are about to spend a season in hell, and that when it's all finished what you've made will have greatness in it. There are quicker movie actors, and God knows there are easier ones to get along with. But there are none better.

Most of us remember seeing him for the first time in 1967 when, gulping and tweeting, he contemplated the silky leg of Anne Bancroft in The Graduate. Even before that, however, Arthur Miller knew who he was. Three years earlier, when he was a fledgling actor, Hoffman had stage-managed an Off Broadway production of Miller's A View from the Bridge, and the director, Ulu Grosbard, had singled him out; Dusty, Grosbard had said, should do Miller's Death of a Salesman someday—he'd make a great Willy Loman. That someday came last year, when Hoffman and Miller mounted a successful new Salesman on Broadway. And this month a film version of that production, redesigned by Tony Walton and directed by Volker Schlondorff, comes to television as a three-hour CBS special. It's not just another televised play; it's a new work, more refined than the Broadway show, and more touching. One feels Hoffman's stubborn drive behind it (with Miller, he acted as executive producer); it has his jitters, his whine, his awkward fervency. He has done with this straw-hat-trail war-horse what he has wanted to do with every vehicle he's ever worked in: he has made it his own.

The need to possess a work has bedeviled Hoffman throughout his career. If he is known as "difficult"—and he is, he is—that's because, as he puts it, "nobody really wants to collaborate. We'd all like to be able to do it ourselves and not have to be diplomatic and talk somebody into why you think what you think. I mean it's like being in front of a canvas and some guy next to you is saying, 'No, use only this color and don't mix it with that.' Each person really believes he's right, and, as a matter of fact, they both are. We'll both paint it brilliantly, but we'll paint it differently."

In the wake of Tootsie and Kramer vs. Kramer, he is among the most "bankable" actors in Hollywood (for his next film, a comedy to be written and directed by Elaine May and co-starring Warren Beatty, his salary is rumored to be $6 million). He has won the right to brook no opposition. "The picture's the most important thing," he says. "Someone once said to me, 'Isn't friendship more important?' and I said, 'No. The friendship is gravy. We didn't go in here to improve our friendship. We didn't both sign the contract to work on our relationship. We signed the contract to make as good a movie as we could.' " Ulu Grosbard, the man who pointed him out to Miller that day in 1964 and remained his friend for the next fourteen years, was called in to direct him in the movie Straight Time; by the film's release in 1978, the two were no longer speaking. And though Tootsie was the best and most successful film Sydney Pollack ever directed, he later confessed that he would work with Hoffman again only "after a long rest, maybe."

"That was a tough marriage," Hoffman admits. "I'd been with the Tootsie project for three years. And Sydney's the kind who is, I don't know—authoritarian. He just wanted to say, 'Now I'm taking over. Now you act.' I had carried the thing, and I told him, 'I can't do that.' So we conflicted. But in crucial areas it was very compatible. Watching the daily rushes, we never disagreed on what was the best take or what didn't work. And that is probably the most uncomfortable situation. By the time you get in the rushes, if you're suddenly sitting next to a director who likes the take most that you like least and vice versa—that's bloody. It's like being married to someone and you disagree on how your kids should be brought up and what school they should go to. It's a blood war."

The rushes afford Hoffman the kind of feedback a stage actor gets from an audience. "I don't care what anybody tells you," he says, "you have to act in front of people. That's what an acting class is: you get up and do a scene and have the other actors, twenty of them or so, sitting there, and in a way you've hired an audience. In film, the rushes help me a lot. Because by the time you get to that stage where you're shooting, you start seeing a lot of stuff you don't like. It's like being a sculptor, you know, putting that piece of clay up there and playing around with it and knocking out stuff. What I'm left with winds up being the character." And what does he knock out? "Acting. Every time the seams show. When you see acting, you try to get rid of it. And then you get surprised. I mean in Tootsie I couldn't have been more surprised to see that woman I played turn out that way. I would have guessed that she would wind up with a more flamboyant personality. But a kind of shy thing crept in, and I think it had to do with how self-conscious I was about the way I looked—that I wasn't as attractive as I wanted to be. No matter what sex you are, you want to be glamorous."

Amid such intense self-examination and role playing, where does Dustin Hoffman find Dustin Hoffman? He seems to view himself the way an athlete might, as a body, a vehicle, an instrument. "The first thing I say when I look in the mirror in the morning," he remarks, "is: 'Did I eat too much last night? Is it showing on my face? Have I been working out enough every day? Am I retarding the aging process as much as possible? Gee, those circles I had under my eyes are gone now.' Or 'Where did that one come from? It wasn't there before.' You're not seeing yourself, you're looking for things. In a sense it's like looking at your own rushes every day. You know, are my seams showing?"

One begins to see where the infamous "difficulties" may lie. "The directors that I like best," he says, "are the kind that don't march up and down in front of the camera before the take, but the kind that get lost, you know, become part of the scenery. And yet they're very strongly there, because they know where to put the camera." On the set, Hoffman likes to participate in other performances. "I hug the side of the camera during the other actor's close-up," he says. "And I'm in a sense directing because I know what the actor's going for and I'm trying to help him reach it. You try to piss him off if he's supposed to be pissed off. Try to move him. Try to make him laugh if it's funny." And if the film's director doesn't go for such shenanigans? "Well, that's where you have to have an agreement with the director before you start. Otherwise it's hard for me. I mean if he can do it, fine. I'll go sit in my room and relax. But, you know, if I feel that I can do it better..." A pause as he searches for tact—"then it's tough."

Some directors love Hoffman's meddling. "I have not worked with a better actor, or a more generous actor," says Robert Benton, who directed him in Kramer vs. Kramer. "Dustin began working with Justin Henry [who played his son in the film] from the beginning. And on the set, Dustin became a father to him. He would discipline the child. And he would coach Justin through the scenes. He was as responsible for the best of Justin's performance as I was, probably more so. Dustin will tell you, and it's true, that he gives his best performance when he's not in front of the camera."

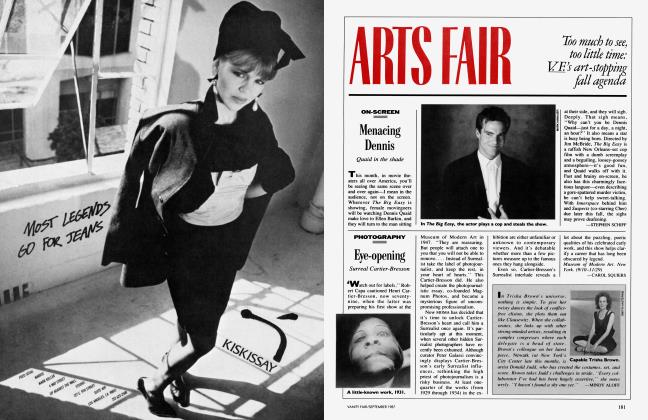

But Hoffman is not among those actors who "become" their roles, who maintain a characterization offscreen as well as on. "I always think it should be the opposite," he says. "In other words, that's for the audience to do. That's not our work. In Death of a Salesman, John Malkovich doesn't become Biff to me; when we're off, it's not Willy and Biff, it's Dustin and John. Our work is to stay as close to the bone as we can, to find out how we can get to each other and kick off each other. I don't know who Willy Loman is. He is whoever the actor is that's playing him. And I don't know who he is when I'm playing him. I mean I'm playing as close to myself as I can." Yet Hoffman s performance in the television version of Death of a Salesman seems definitive—not a Willy Loman, but the Willy Loman: at times he seems bigger than the play itself. And this may be a good thing, for even in its latest incarnation Salesman is not the Great American Drama it's cracked up to be. It still shudders under all that populist "poetry," under those hambone theatrical devices—the second-act revelation, for instance, and the tycoon brother, Ben, whose shade keeps showing up in a Big Daddy suit to dispense Dale Carnegie homilies. Salesman is repetitive; it has longueurs. There's something sleazily self-aggrandizing about its huffing and puffing over how "attention must be paid." After all, if honor is due Willy Loman, it must certainly be due the script that hatched him. So Death of a Salesman browbeats its audience; it makes one feel guilty— even inhumane—for not applauding.

"The picture's the most important thing. Someone once said to me, Isn't friendship more important?' and I said, 'No... We didn't sign the contract to work on our relationship.'"

But as a piece of drama, the thing moves. For all his piety and cornball humanism, Miller is a crafty scene builder; he knows how to zip from concord to conflict and back in a way that startles the audience and roils its emotions. Salesman works musically; it's as schmaltzy and compelling as a Tchaikovsky symphony, and Dustin Hoffman knows how to play it. He is one of a very few actors who have mastered both stage and screen, and who understand the difference between them. His performance in the TV film hasn't merely been toned down from his Broadway stint; it's been reconceived. This new Willy groans his lines, pumping them out from a well of fatigue. He's a man whose engine is on the fritz, like the Chevrolet he both adores and reviles—a jalopy tootling heedlessly toward the junk heap, developing new rattles and squeaks at every turn. If a dying machine has to work harder to cover the territory, Hoffman makes Willy scurry, his little feet hammering like pistons, his mind racing toward the end of a thought, hitting a wall, and then bouncing away. He's cheerful and feisty and loud, because he's a salesman trying to sell the whole world on his lie—trying to distract himself and everyone around him from the knowledge that he's running on empty.

Lee J. Cobb's brawny, lugubrious portrayal was certainly the definitive Willy of the fifties, but Death of a Salesman looked like a very different play then. During the first decade or two after the play's initial staging in 1949, Willy's yearning to be a hotshot salesman could seem perfectly plausible, because America was a manufacturing giant selling brave new goods to a hungry world. Hoffman's dinky, shuffling "shrimp" is a Willy for the eighties, for an age of paper pushers and greenmailers and arbitrage tycoons. Services and systems are now the great American products, and a salesman can no longer even dream, as Willy has dreamed, of being a proud warrior in freedom's front rank. These days he's just a foot soldier in the retreating army of big industry. If Cobb's performance was about gigantic disappointment, about dreaming big and failing, Hoffman's is about starting small and shrinking, about being minuscule in an age of small aspirations, small expectations, small giants. His Willy Loman is what happens to The Graduate when he finds he can't even make a killing in plastics.

Hoffman and Miller had just finished editing the film version of Death of a Salesman when Vanity Fair asked them to talk about their work together. The conversation took place in Hoffman's Fifth Avenue office, and while he waited for Miller to arrive, Hoffman entertained himself and the room at large—a secretary, a publicist, an editor from the magazine—with comments on the activity in the street below his window. "Some of the best-looking girls in the world walk down that street," he chortled, peering through a large pair of binoculars kept on hand, apparently for just this purpose. The monologue about the girls continued for several minutes, until Miller loped dutifully into the room. He slouched in a corner armchair. Hoffman perched beside him, animated and expansive.

D. H. Arthur, this play was written before there was a tube, although there were movies. Did you think then that it might be seen anywhere besides the stage?

A.M. No. Never. But it was made into a film in 1951. Freddie March did that one. And then it was made into an abbreviated television thing with Lee Cobb.

D.H. I might interject that there was no attempt made at that time to find out if Arthur Miller was interested in doing the screenplay of his own play. You were box-office poison then, weren't you? The New York writer is box-office poison.

A.M. What they wanted was a Hollywood movie, which was more or less what they got. They chopped off all the climaxes, almost like a lawn mower. Don't ask me why. In Hollywood they always tried to destroy the quality of a play. They would pretend that it was a movie. Sometimes it worked out. But it's very difficult to deal with this play, for the simple reason that already on the stage it has filmmaking elements in it. The way the time changes, the locales, the way people appear and disappear.

D.H. It's a screenplay rhythmically. Steven Spielberg said to me that when you're in the audience watching this play you are the editor, you decide where you should be focusing. So the trick was to translate that onto film and not destroy the play. In other words, not cut it.

A.M. Nothing was cut from the play this time. I think I added one line. But you get the feeling you're watching a film event. That's really due to the director, Volker Schöndorff, and Tony Walton's scenery.

V.F. Did you have something definite in mind for Walton?

A.M. I knew we shouldn't be in a literally real Brooklyn house, the idea of a house.

D.H. The reason for that is that this is not the story of Linda and Willy Loman and their sons, Biff and Happy. This is the story of the family America. In '45 we won the war and everything was supposed to be incredible after that. The American Dream was supposed to work. By 1949 there were a lot of people shaking in this country. What makes the play exciting is that it hits in reverb. We are shaking again right now. The country is shaking.

A.M. Yes, curious about that. It has become a contemporary work. It's more up-to-date now.

D.H. This play was the first play I ever read. I had never thought about acting. I was studying to be a pianist. But in high school I took an acting class and liked it, and my brother gave me a book of the seventeen best American plays. The first play was Death of a Salesman. Something happened to me when I read that play that had never happened to me before. It had nothing to do with acting, it had to do with my family, and I simply could not talk about that to anyone. I would just go off into corners and start weeping. The play is still an emotional experience for me. In a sense I can't talk about the play without mourning Willy Loman.

V.F. Now that you've done the play so many times, haven't you gotten used to it?

D.H. You can't get used to something that you can't get right.

V.F. Do you think you've gotten it right in the film? Can you edit your performance into the perfect one?

A.M. You get the best you can do that week, that's all.

D.H. You are not allowed to do a retake today unless you get down on your knees and cough up something akin to a point. Every day that you want to shoot over is, what, fifty grand? We shot this play in twenty-five days. A hundred and seventy pages in twenty-five days. I never did anything like that before in my life.

But it was a pleasure to be in the ring with this play. That's what you feel like. You get in the ring with this heavyweight champion that really is your adversary, because it calls out your limitations. You have to do it a certain way. You cannot do this play on a stage longer than an hour and six minutes. If you go over you're doing something wrong. Now, when you get on film you've got to cut that in half, because a minute in life is five minutes on the stage and ten minutes on film. That's just the nature of it.

A.M. In production we attempted to make something that won't oppress you with the fact that you're watching a play on television.

D.H. We remind you from time to time that you are watching something that was written as a play. But at the same time you are sitting at the kitchen table with this family. You can brush their skin. It's magic. It's akin to Fellini's Roma, where at one point there is a huge horrible car crash out on a freeway. And when you see that on film it's like you're right there on a freeway watching a horrible car crash. But Fellini did it inside a studio.

V.F. Did the performances prepared for the Broadway stage have to be adjusted a lot for the film version?

A.M. They can't use the vocal levels they used on the stage.

D.H. It looks like you're doing Macbeth or Lear suddenly.

A.M. John Malkovich didn't very raise his voice very much on-stage , so there wasn't very far for him to go. But the rest of them had to create the same emotion at a much lower vocal level. The microphone is six inches over your head, you know.

D.H. A play is written to reach the last person in the last balcony. Usually playwrights have a particular penchant for the ones up there. So suddenly it's redundant to act the way that you did on the stage. I'd like to do it on the stage again in about a year and a half. I think it's one of those things it would be nice not to ever let go of. It would be great to do it when I don't have to put on makeup—just walk in off the street onto the stage.

A.M. I don't know of any actor who could do that. Actors that age would be dead after the first act. Cobb was thirty-seven when he did it, although everybody thinks he was sixty-five. Onstage he wasn't old-looking at all. You look on the screen fifteen years older than Lee did.

D.H. Well, if you were writing the play now, you would not make Willy Loman sixty-three years old. Now your average life span is seventy-four. But nothing is old today, unless they can't fix it on the surgery table.

What makes the play really exciting to attempt, or to see, for that matter, is that if it succeeds the audience is not aware of all this technical stuff we're talking about. The guys in the saloon are going to be watching something that looks like they're in somebody's home. And in fact that's the audience we want to reach. As Arthur says, the audience that you really want to reach when you write a play today can't afford to go anywhere near the theater. You know, Art directed the play in China just before this. And, my God, how many times did he hear, "The Chinese aren't going to emotionally go for this play. What the fuck do the Chinese care about the capitalist dream, or nightmare, or whatever?" But they jumped on it.

A.M. The play is a tragedy of a believer. I guess people that's what makes Willy so familiar a person. Most people in most countries to some degree go along with what's happening. They try within the parameters given to succeed. In China they originally thought they could stand apart from the play as a critique of capitalism. But the more we rehearsed the show, the more they saw it was about China too. In the beginning they played it with almost a satiric edge—as to Willy's claims for himself, for his optimism about selling stuff, and so on. Then the satiric edge vanished and they really began to take him seriously. As one of them said, "We are a people with so many illusions." Look what happened in the Cultural Revolution. They spent ten years chasing a dream and destroying the whole country, on a completely optimistic basis. The key line in the play is that Willy never made a lot of money and his name was never in the paper, but you've got to pay attention to him. And that's just the way they felt.

D.H. You do love Willy. He's an innocent. And a great American. All he wants to do is to use his hands on a house, rebuild it. Willy Loman at three in the morning, or whatever it is, on the last night of his life is out there not only planting a garden but at various times fixing his house. And if I was allowed to be as pompous as I wanted, I would say that the reason people were so affected by this play when we did it on the stage is because this country today is outside in the middle of the night with a hammer and a nail fixing a shingle on its house. There's something moving about the people in this country today feeling totally helpless in terms of where we're going, just helpless.

Do you know what I used to do? In the Broadhurst Theatre there were plenty of places where I got offstage. Linda had a tremendous aria, or Biff or Happy. Usually one of us was onstage. So they had a chair in the back for me. That's how I would rest. And I would look through the canvas. For some reason the lighting made it possible to see the audience extremely clearly. And there was always one guy in the second row sleeping. But he was sleeping after the first scene. Sometimes he was sleeping ten minutes into it. So I chose to believe that those were the guys who right away they said, "That guy Willy, that's me. So good night." Because it was that kind of a sleep. It was like falling asleep on the analyst's couch. But I used to watch that audience, man, and I'll tell you, I'll never forget it. I mean they sat forward. It was wonderful. Every age. If I ever do it again I'm going to secrete a documentary-film camera to be able to get that. It really is an experience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now