Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

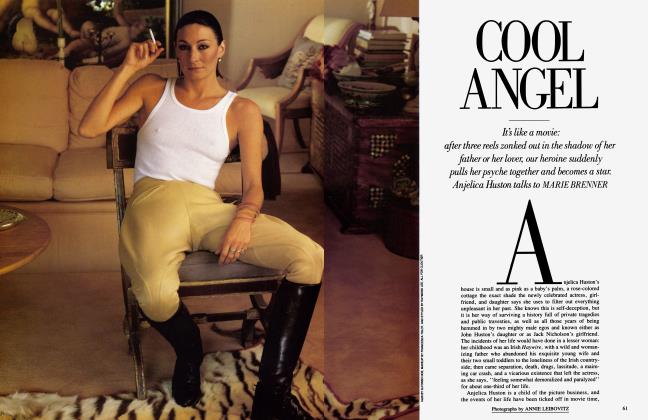

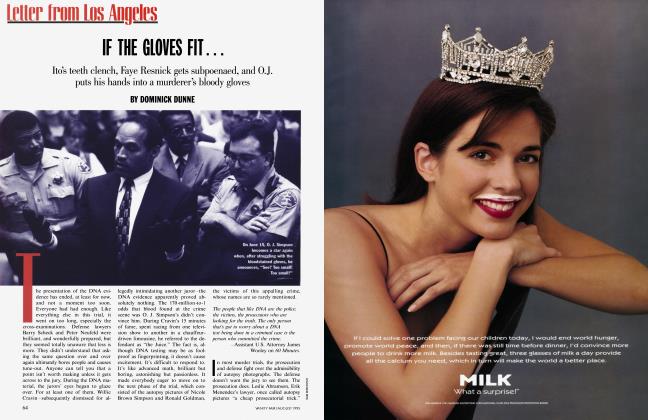

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDOMINICK DUNNE continues his investigation into the social web of Claus von Bülow, probing deeper into the shadowy cast of characters

September 1985 Dominick Dunne Marc BoxerDOMINICK DUNNE continues his investigation into the social web of Claus von Bülow, probing deeper into the shadowy cast of characters

September 1985 Dominick Dunne Marc BoxerFor the eight weeks that the trial of Danish socialite Claus von Bülow, for twice attempting to murder his heiress wife by insulin injection, mesmerized the country, a related development of the strange case ran its parallel course. Nowhere was the scent of rot more pervasive than in the minimally publicized story of a Providence parish priest, Father Philip Magaldi, and his onetime companion David Marriott, an unemployed mystery man who drove around in limousines and who was happy to show anyone who cared to look Xeroxed copies of his hotel bills from Puerto Rican resorts, which he claimed were paid for by Claus von Bülow. Why, people wondered, if von Bülow was innocent, would he have involved himself in such an unsavory atmosphere?

Let us backtrack.

On July 21, 1983, Father Magaldi, on the stationery of Saint Anthony Church, 5 Gibbs Street, North Providence, Rhode Island, wrote and signed the following statement in the presence of a notary:

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

... I wish to state that I am ready to testify, if necessary, and under oath, that DAVID MARRIOTT did in fact discuss with me in professional consultation, his delivering to Mr. Claus von Bülow's stepson, Alexander [von Auersperg], packages which he thought contained drapery materials from his friend Gilbert [Jackson] in Boston, but on one occasion a package which he opened contained drugs which were delivered to the Newport mansion and accepted by Mrs. Sunny von Bülow who stated Alexander was not home but she had been expecting the package.

My reason in writing this affidavit is that in the event of accident or death, I wish to leave testimony as to the veracity of the statements made to me by DAVID MARRIOTT and also that as his counselor in spiritual matters, I advised him to inform Mr. Claus von Bülow and his lawyers as to what he knew concerning drug involvement by Alexander. I intend to speak with Mr. Roberts, the Attorney General of the State of Rhode Island, concerning these matters in August.

Five days later, on white watermarked stationery bearing the engraved address 960 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, Claus von Bülow wrote Father Magaldi a letter that was quoted in the New York Post by gossip columnist Cindy Adams at the conclusion of the second trial. It reads in part:

Dear Father Magaldi,

I want to thank you for your kindness and courage in braving the storm and the airport delays, and then coming to meet me in New York. Had I been able to contact you in Boston I would gladly have faced those problems myself.

We were however rewarded with a very enjoyable evening, and I am grateful to you.

I want to repeat my wish to consult with you in finding an acceptable charity for donating the royalties of my book. The total profits, including film rights, could be anything between $500,000 and $1,000,000. . . .I will be happy to meet with you in Providence, Boston or New York at your convenience.

On September 30, 1983, Father Magaldi, in a document notarized by his attorney, William A. Dimitri, Jr. (who later became the attorney for von Bülow's mistress, Andrea Reynolds), made the following statement:

In addition to my affidavit I wish to state something which I feel is too delicate a matter to come before the media and public at this time.

I refer to pictures shown me by David Marriott in which Alexander is engaged in homosexual activity with an unidentified male whom David told me was Gilbert Jackson.

Because these pictures in my estimation served no purpose and were patently pornographic, I destroyed them. However I can state that I recognized Alexander in the picture but cannot verify that the other was Gilbert Jackson since I have never seen him. In actuality, Father Magaldi had never met Alexander von Auersperg, and Alexander von Auersperg had never met Gilbert Jackson, who was murdered in 1978, and therefore no such pornographic pictures ever existed for Father Magaldi to destroy. In other, more exotic areas of his life, Father Magaldi traveled in the netherworld of Boston under the alias Paul Marino. It was in this role that he had met David Marriott, in the Greyhound bus terminal in 1977, and not in the spiritual capacity he claimed in his affidavit. David Marriott told me that he did not know his benefactor was a Catholic priest until Magaldi was in a minor automobile accident several years after their friendship began and his true identity came out.

Marriott, who participated in preparing these and other affidavits besmirching the names of Claus von Bülow's wife, Sunny, and his stepson, Alexander von Auersperg, later claimed that they were all lies and that he had been paid by von Bülow for his part in the deception. Furthermore, Marriott had secretly tape-recorded conversations with Father Magaldi, von Bülow, and Andrea Reynolds to attempt to support his claim. On one tape that I listened to, Father Magaldi and Marriott discuss von Bülow's alleged offer to help the priest be elevated to bishop. On another there is talk about getting the late Raymond Patriarca, the Mafia chieftain of Providence, to get a drug dealer serving time in jail to say that Alexander von Auersperg had been one of his customers.

This murky matter played no part in Claus von Bülow's second trial in Providence. However, there were frequent rumors that Father Magaldi, who is a popular priest in the city, was about to be indicted for lying in a sworn statement he had given in 1983 to help von Bülow get a new trial, and that may have been the principal reason why Judge Corinne Grande insisted that the jury be sequestered for the eight weeks of the trial, especially since several of the members were acquainted with Father Magaldi. The priest was not indicted until after the jury had retired to deliberate, and the contents of the sealed indictment were not made known.

On the day before the jury returned its verdict, Claus von Bülow and Father Magaldi met—perhaps by accident, perhaps by design—in the lobby of the Biltmore Plaza Hotel. The encounter took place at seven o'clock on a Sunday morning and was witnessed by one of the bellmen, who used to serve as an altar boy for Father Magaldi. The priest, the bellman told me, had made the fifteen-minute drive from North Providence to buy the Sunday papers at the newsstand in the lobby of the hotel. Just as he arrived, the elevator doors opened and von Bülow emerged to walk Mrs. Reynolds's golden retriever, Tiger Lily. The encounter between the two men was brief, but the bellman was sure they had exchanged a few words.

That night, twelve members of the media who had covered the trial gathered for a farewell dinner in a Providence restaurant. Their conversation never strayed far from the subject that had held them together for nearly nine weeks—the trial. They discussed the fact that once again Claus von Bülow had not taken the stand, and they felt that it had been a foregone conclusion in the defense strategy from the start that he was never going to. The defense was aware that the prosecution was in possession of an exhaustive report by a European private-detective agency on the life of von Bülow before his marriage to Sunny, and a clever prosecutor, given the opportunity to examine the defendant directly, would have been able to ask many potentially embarrassing questions. Another topic of conversation was Judge Corinne Grande, whose frequent rulings favorable to the defense raised questions of her impartiality. In what was certainly the most controversial ruling of the trial, Judge Grande had agreed with von Bulow's lawyers that the testimony of G. Morris Gurley, Sunny's banker at the Chemical Bank in New York, should be barred. Gurley would certainly have testified that, according to a prenuptial agreement, von Bülow would receive nothing from his wife in a divorce. However, according to her will, he would inherit $14 million if she died.

I repeated a story I had heard that afternoon from someone who had been present at an exchange between Mr. Gurley and Alexandra Isles in the witness room. Mrs. Isles had just completed her testimony when Gurley was informed that he would not be called to the stand. Gurley was stunned. So was Mrs. Isles. "I can't believe they're not letting you testify," she told him. ''I wasn't the motive, Morris. The money was the motive. He had me for free."

Late in the evening someone came up with the idea, since there were twelve of us, of pretending to be a jury and voting a verdict, not as we anticipated the jury would vote but as we would vote if we were members of the jury and knew everything we knew rather than what Judge Grande had selected for us to know. The waitress brought a pad and pencils, and each person cast his vote. Our verdict, we all agreed, would remain our secret.

During the four days the jury was out deliberating, Claus von Bülow wandered up and down the crowded corridors of the courthouse, chain-smoking Vantage cigarettes and behaving like a genial host at a liquor-less cocktail party, moving from one group of reporters to another with his endless supply of anecdotes. He even took time to call his most consistently loyal friend, the art historian John Richardson, to ask when he planned to leave for London. Monday week, he was told. He asked Richardson if he would take twelve large bags of potato chips to Paul Getty, Jr., who loved potato chips, but only the American kind.

On Monday morning, while waiting for the jury to reappear, von Bülow was tense and withdrawn. In the minutes before the jury entered, Barbara Nevins, a popular CBS reporter, leaned over from the press box and asked him if he had any final words before the verdict was delivered. In an uncharacteristic gesture, von Bülow raised the middle finger of his left hand to her.

"Is that for me, Mr. von Bülow, or for the press in general?" asked Miss Nevins. Thinking better of his gesture, he pretended that he had meant to scratch his forehead. At that moment the jury entered.

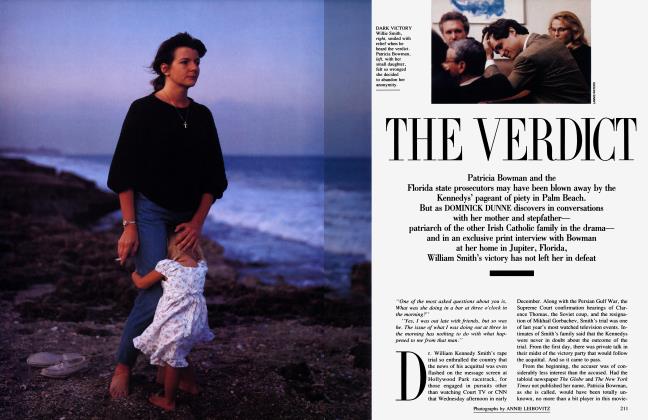

The proceedings were swift. The verdict was, predictably, Not Guilty on both charges. Von Bülow bowed his head for an instant and blinked back a tear. Then he and his lawyer Thomas Puccio nodded to each other without emotion. The courtroom was strangely mute despite a few cheers from elderly Clausettes in the back of the room. Very little of the ecstasy that accompanies a vindication was present, except in the histrionics of Mrs. Reynolds, whose moment had finally come, and she played it to the hilt. Flanked by two of her favorite reporters and directly in line with the television camera, she raised her diamond-ringed fingers to her diamond-earringed ears and wept.

During the triumphant press conference after the trial, von Bülow, surrounded by seven lawyers glowing with the flush of victory, returned to his old arrogance as he fielded questions from media representatives he no longer needed to court. Following a champagne visit with the jury that had acquitted him, he and Mrs. Reynolds returned to New York. Even in his moment of victory, dramatic rumors preceded his arrival. At Mortimer's restaurant, a French visitor said that if Claus had been found guilty, there was a plan to spirit him out of the country on the private jet of a vastly rich Texan.

'If I took you down to our beach and you started asking people, the two hundred of us who have dinner and swim and play golf together, you would find nearly everybody will say he did it," Mrs. John Slocum, a member of Newport society whose pedigree goes back twelve generations, told a reporter a week before von Bülow was acquitted. "And I'll tell you something else," she added, "people are afraid of Claus."

A few days after the trial, I went to Newport to check out the scene, and found that the battle lines between the pro- and anti-von Bülow factions remained drawn, and seemed possibly even fiercer than ever. On the front page of the Newport Daily News, Mrs. Slocum crossed swords with Mrs. John Nicholas Brown, who had been von Bülow's staunchest defender in Newport society from the beginning, in their respective damnation and praise of Judge Grande and the verdict. In the same article Mrs. Claiborne Pell, the wife of Senator Pell of Rhode Island, said she was "delighted" that von Bülow had walked from the courthouse a free man, while Hugh D. Auchincloss, the stepbrother of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who had once written a letter in von Bülow's behalf to help him gain membership in the Knickerbocker Club, had harsh words for the verdict, the judge, and his former friend. At the exclusive Clambake Club, Russell Aitken, the widower of Sunny von Bülow's mother, Annie-Laurie Aitken, stared ahead stone-faced as Mr. and Mrs. John Winslow, who had once said that the Aitkens would not be welcome at Bailey's Beach if Claus were acquitted, were seated nearby with their party. The Winslows were equally stone-faced.

Russell Aitken's dislike of his stepson-in-law is ferocious, and it predates the two charges of attempted murder by insulin injection. Standing on the terrace of Champs Soleil, the Bellevue Avenue estate he inherited from his late wife, which rivals, perhaps even surpasses, Clarendon Court in splendor, Mr. Aitken recalled for me the first time he and his wife ever met Claus von Bulow. It was in 1966 in London, in the lounge of Claridge's hotel, when von Bülow was a suitor for Sunny, who had just divorced Prince Alfie von Auersperg. Von Bülow arrived for the meeting with Sunny's parents with his head covered in bandages, explaining that he had been in an automobile accident. Later Mr. and Mrs. Aitken heard from Sunny that the truth was rather different: his head was bandaged because he had just had his first hair-transplant operation.

Behind Russell Aitken, on the rolling lawns of the French manor house, a new croquet court was under construction, which promises to be the handsomest croquet court on the Eastern Seaboard. A respected sculptor, he had had one of his own artworks installed on a wall overlooking the new court. Mr. Aitken interrupted his tour to continue our conversation about his stepson-in-law. "He is an extremely dangerous man," he said, "because he's a Cambridge-educated con man with legal training. He is totally amoral, greedy as a wolverine, cold-blooded as a snake. And I apologize to the snake."

"May I quote you saying that, Mr. Aitken?" I asked.

"Oh, yes, indeed," he replied.

While for an von exclusive Bülow interview saved himself with Barbara Walters on 2020, his mistress did a saturation booking on the television shows. Back in Providence, Judge Grande defended herself against a barrage of criticism that she had let a guilty man walk free.

'I DIDN'T HELP CLAUS BEAT RAP,' Went One headline. Out in Seattle, Jennie Bülow, the elderly widow of Frits Bulow, Claus von Bülow's long-dead maternal grandfather, from whom he acquired his name when he changed it from Borberg, made no secret of her dissatisfaction with both the judge and the verdict.

In New York, von Bülow announced that he would visit Sunny at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center for the first time in four years as a gesture of his continuing love for her. Later, seated in the library of his wife's Fifth Avenue apartment, he met with Barbara Walters, as he had met with her at the conclusion of his first trial. He talked about his desire to go back to work. "I was never going to divorce Sunny because of any other woman," he told her. "I was going to divorce Sunny because she didn't tolerate my work." At the end of the interview, Miss Walters announced that von Bülow would soon be leaving for England to begin work for Paul Getty, Jr., the son of his former boss.

Getty, who was very possibly the donor of both von Bülow's bail money and his defense fund, is fifty-two years old and makes his home in England. He recently gave $63 million to the National Gallery in London. In 1984, according to Fortune magazine, he had an income from the Getty trust of $110 million. A virtual recluse, Getty is said to be a registered drug addict in England. His second wife, Talitha Pol, a popular member of the jet set, died in her husband's penthouse apartment in Rome of a massive overdose of heroin in 1971. To this day many of her friends insist that the fatal injection was not self-administered. The oldest of Getty's five children, John Paul III, lost an ear during his kidnapping in Italy in 1973. He later suffered a methadone-induced stroke that left him blind and crippled. Getty's youngest child, Tara Gabriel Galaxy Gramaphone Getty, seventeen, the son of Talitha, is at present engaged in legal proceedings against the $4 billion Getty trust.

In the ongoing controversy that constantly surrounds him, von Bülow for some reason denied to reporter Ellen Fleysher during a news conference an item in Liz Smith's syndicated column saying that he and Mrs. Reynolds had posed for Vanity Fair magazine and photographer Helmut Newton dressed in black leather. "No, I think you've got the wrong case," he told the reporter. Liz Smith, quick to respond, printed in her column two days later, "Once you see Claus inside the magazine in his black leather jacket, I want you to tell me how we can believe anything he says."

The same day that Liz Smith questioned von Bülow's veracity, the New York Times reported that the indictment against Father Magaldi in Providence had been unsealed and that the priest was charged with perjury and conspiring to obstruct justice to affect the outcome of Claus von Bülow's appeal. Early that morning the telephone rang in my New York apartment. It was Mrs. Reynolds. Displeased with the latest developments in the media, she accused me of planting the story in Liz Smith's column to attract publicity for my article in Vanity Fair.

"Do you have any fear of being subpoenaed in the Father Magaldi case?" I asked her.

"They wouldn't subpoena me over their dead bodies," replied Mrs. Reynolds.

"Why?"

"I can totally demolish Mr. Marriott," she said. There was ice in her voice.

I asked her if it was true that she and von Bülow were only waiting for the return of his passport so that they could get out of the country before they were subpoenaed. She angrily denied to me that they had played any part in the false affidavits.

Von Bülow now got on the line, and his anger equaled that of Mrs. Reynolds. "I suggest you talk with Professor Dershowitz at Harvard," he told me sternly.

"Let me give you his telephone number," snapped Mrs. Reynolds, "to save you the seventy-five cents it will cost you to dial information."

The burning question was, would Claus von Bülow's acquittal give him automatic use of his comatose wife's $3.5 million annual income, minus, of course, the half-million dollars a year it costs to maintain her in Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center? If so, his access to the money was not immediate, and civil litigation loomed that could tie up Sunny's fortune for years. In the meantime, unless Sunny dies and von Bülow inherits the $14 million that he is guaranteed in her will, he will have to make do with the interest on the $2 million trust his wife gave to the Metropolitan Opera, which amounts to $120,000 a year before taxes. There was talk in the first week of his freedom that money was tight.

Despite the wide coverage of von Bülow's acquittal across the country, the accolades of victory were spare in New York. The jewelry designer Kenneth Jay Lane entertained von Bülow and Mrs. Reynolds at a lunch in their honor—cold curried chicken, pasta salad, raspberries and blueberries with creme fraîche—and the guest list included John Richardson, Giorgio co-owner Gale Hay man, the English film star Rachel Ward, her husband, Australian actor Bryan Brown, and her mother, Claire Ward, longtime companion of von Bülow's great friend Lord Lambton, a former parliamentary undersecretary for the Royal Air Force who was forced to resign after his involvement in a government sex scandal. The lunch coincided with the announcement in the New York Times of Father Magaldi's indictment, and one guest reported that the atmosphere was subdued.

While von Bülow waited for his passport to be returned, he and Mrs. Reynolds became—for them, at least— almost socially invisible. They lunched quietly at Le Cirque with their staunch ally Alice Mason, the New York realtor and hostess. On another occasion Mrs. Reynolds entertained two members of the press at lunch at the Four Seasons. They attended a coming-out party given in honor of two daughters of the family with whom Cosima had lived during the first trial. For some reason they did not once venture into Mortimer's, the Upper East Side restaurant that had become their favorite haunt between trials.

Mrs. Reynolds told friends she was writing a mini-series based on the trial. Von Bülow made plans with his publisher for his autobiography and, according to one friend, made arrangements for a face-lift. Together they visited the Livingston Manor house of Mrs. Reynolds's about-to-be-former husband, Sheldon Reynolds, to look at trees she had planted and pick up clothes she had left there. A witness to the scene reported that von Bülow's attitude to Mrs. Reynolds was chilly.

Alexandra Isles declined to be interviewed at the end of the trial. "We all have our own ways of surviving,'' she wrote me. "Mine is to try to put it out of my head and get on with other things. I know you will understand that an interview somehow keeps it all 'unfinished business,' but here is a bit of irony you are welcome to use: It was my father who, in the Danish underground, got little Claus Borberg (in his boy scout uniform!) out of Denmark.''

The participants began to scatter. Maria Schrallhammer, after twenty-eight years of service with Sunny Crawford von Auersperg von Bülow and her children, retired and returned to Germany the day after the verdict. Cosima von Bülow, eighteen, threw herself into the hectic whirl of a summer of debutante parties. Alexander von Auersperg returned to his job in the retirement division of E. F. Hutton. Ala Kneissl, pregnant with her second child, began work on a documentary film about victims of homicide. Together Ala and Alexander, through the Chemical Bank, which handles the fortunes of their mother and grandmother, are in the process of establishing two major foundations. One will provide funds for the solace of the families of homicide victims and for changes in legislation to allow victims' rights to equate with the rights of criminals. A second foundation, commemorating both their parents, will be for medical research in the field of comas. G. Morris Gurley, the bank officer who was not allowed to testify at the trial, is in charge of overseeing the foundations.

Von Bülow did not visit his wife at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center. Two weeks after the acquittal, his passport was returned to him, and for the first time in five years he was free to travel abroad. The next day he and Mrs. Reynolds left New York. They did not fly first-class. He stopped in London to visit friends. Mrs. Reynolds, after a one-day stopover in London, went on to Geneva to visit her father. A few days later they rendezvoused at the Grand Hotel e la Pace in the Italian spa of Montecatini Terme.

The third act of the von Bülow affair is still to be played. Will Father Magaldi be tried for lying in a sworn statement he gave to help von Bülow get a new trial? Will David Marriott, who once said and later recanted that he had delivered drugs, needles, and a hypodermic syringe to Clarendon Court, testify against his former friend and benefactor? Will Claus von Bülow and Mrs. Reynolds be called to testify at Father Magaldi's trial? Will the relationship of von Bülow and Mrs. Reynolds sustain the serenity of his acquittal,"with or without Sunny's income of $3.5 million a year? Will New York and London society receive the couple back into the charmed circles at the top?

The drama seems a long way from the final curtain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now