Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

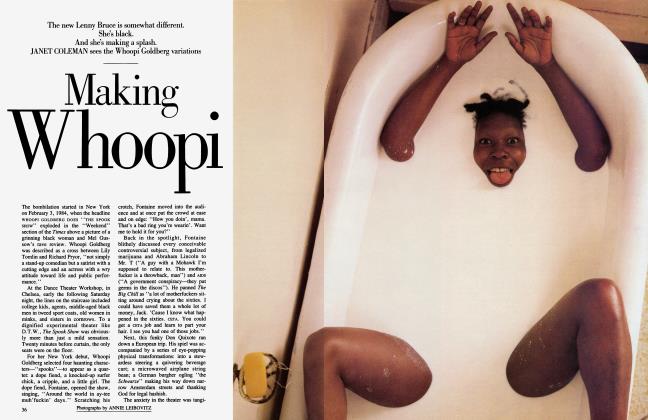

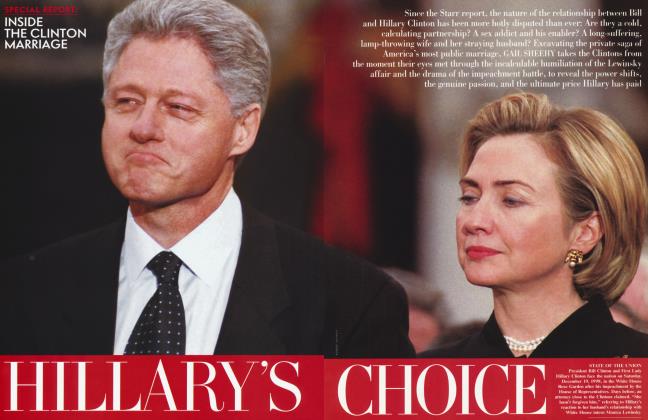

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhile the senator from Colorado campaigned vigorously, he hid one thing from the American public. Himself. GAIL SHEEHY trailed him to find out why

July 1984 Gail Sheehy Jeff JacobsonWhile the senator from Colorado campaigned vigorously, he hid one thing from the American public. Himself. GAIL SHEEHY trailed him to find out why

July 1984 Gail Sheehy Jeff JacobsonI'm an obscure man, and I intend to remain that way. I never reveal who I really am. —Gary Hart

When you find out who Gary Hart is, let me know. —Refrain of Hart's associates

Gary Hart is a passionate man—at least about the issues. He can wear down a dinner table with his intense feelings about arms control. He cannot bear to think of his son's blood or anyone else's being spilled in war. Yet as the voters perceived him, he was cool, aloof, even tame. And there is the central irony of the man. His passions, both political and personal, have remained hidden through this long campaign.

"Be passionate," his advisers exhorted. But Hart made all sorts of excuses for what he would not, and apparently could not, do. "Merely standing up and getting red in the face, clenching your fists and saying 'I'm compassionate' doesn't help one poor person," he insisted on Face the Nation. Up against good old Uncle Walter and Preacher Jesse in his own party, not to mention the True Believer in the White House, this rigidly compartmentalized candidate did not come across as a natural man.

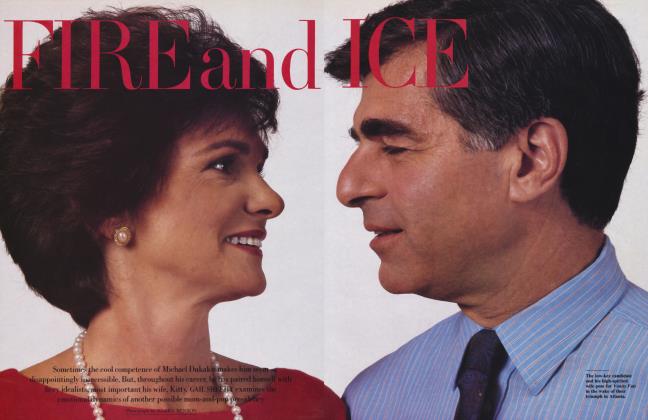

The strain of the campaign shows in Lee Hart, in the grooves of fatigue around her mouth, the weedy hair. Hoarse and fidgety, she can't stop trying to please

There is nothing unnatural about Hart, in the sense of artificial or packaged; quite the reverse. But would he sit on your stoop and down a beer? Would he scratch your dog, let your baby muss his hair, swap a story about his pistol-packin' Grandpa Hartpence for the one about your crazy Polish son-in-law? Doesn't he ever loosen his tie? Has there ever been a bad news photo of him? Will he ever stop looking so video-perfect?

Some grass-roots organizer booked him for a last-minute, totally uncharacteristic appearance in a black church in Philadelphia. Hart was pressed into a corner by a gang of bodies, half of them kids who had knocked off break dancing on the curb outside to come in and take a look at this smooth talker. It was an almost moment. I was reminded of the fervor I had seen evoked by Bobby Kennedy's campaign, as when he jumped from a moving convertible to rush into a black barbershop, or when he was nearly drowned in a whirlpool of ecstatic Hispanics on an airstrip in L.A. I recalled Jack Kennedy, and women running out of beauty parlors in their curlers to shout after his motorcade, "Touch him for me!"

But this is not Hart. His body language said to the black kids, "Don't touch." When he calls staff members into his Senate office to work on a problem and the young ones press in all eager and enthusiastic, Hart will suddenly freeze and say, "You're crowding too close."

Senator William Cohen, a Capitol Hill colleague who has been collaborating with Hart over the past four years on a fictional thriller, echoed sentiments often expressed by those familiar enough with the man to be sure of his substance. "Ordinarily, you'll find him in a corner discussing issues, not moving through the banquet hall touching tables as we're expected to do. I find that an admirable trait, not one to be demeaned."

Of course, the American public wants it both ways. The ideal candidate is charming and amiably superficial when the occasion calls for it, someone who can tell a joke or give a homily even if he gets the facts wrong, as long as he touches common values. At the same time, the public wants a leader who is authentic, which Hart is, and inwardly consistent, which, at this stage in his life, Hart is not.

I asked Gary Hart why he thought his campaign had lost its momentum last April. He insisted, as he would obdurately do in the ensuing weeks, "I start back with the premise that six weeks ago nobody knew who I was. As people get to know me, they'll respond."

What was remarkable about New Hampshire was that people did respond. Excitement sizzled in lunch-table conversations and over long-distance lines: What do you think about this Gary Hart? As long as Mondale was sunk in his own pulp, the complacent front-runner, he resembled overripe fruit. Along came a brash young outsider who appeared carved out of western pine, but in an eastern, trying-to-look-like-Kennedy mold, and he was intriguing.

Voters want to find archetypes in the candidates. Before New Hampshire, Hart was the Gentleman Caller of American politics—the illusory romantic figure who might offer escape from the decadent old ways. Mondale was cast as the Wimp. People gave Hart, this New Generation Democrat, the once-over. But they couldn't find him. Hart became frustrated and often icy when confronted with the "Where's the beef?" charge. God knows, if any candidate had been talking issues for more than a year, it was he. But pollsters will tell you that people don't vote on issues. In presidential elections, most people vote on character. And character is a perceived combination of those traits that—together with the values he represents—set a person apart. People heard Gary Hart's ideas, all right. What they didn't hear in his voice or couldn't sense in his presence was what he really believes in.

One California voter's feelings reflected the sixth sense of hundreds of people I talked to in following Hart around the country.

"I don't know who Gary Hart is or what he stands for," said Margo Winkler, wife of Irwin Winkler, who co-produced The Right Stuff. "Once before, I voted for a stranger because he promised change. He broke my heart. I'll never make that mistake again."

Journalist Bob Woodward, who maintains a kind of halfway house in Washington for bachelorized politicians and who took Hart in during his marital separations, has said about Hart, "He'd make a better president than a candidate."

The same ironic tension between Hart's outer, self-effacing presentation and his inner, exalted confidence was summed up by one of his advisers: "He believes he'd make the best president since Jefferson, but he can't walk into a room and put himself across."

"Why is it that the more voters get a look at you, the more they seem to turn off?" I asked Hart at the midway point in the primaries.

His eyes said, "I know." His voice was injured: "But why do they assume I'm hiding something?"

"It's because he is hiding something," said a close associate. "He's hiding himself."

The chartered silver bullet, in which he has been virtually sealed for more than three months, is on its way to Hart's home in Denver. It is April 11, and Gary Hart, who "read the waters" and believed the country was ready to risk change, has been through the rapids of abrupt national fame and over the falls. The last two weeks have been punishing. He lost it in New York and he is drowning in Pennsylvania.

Members of the traveling press sit with their portable computers listlessly oinking away. They are as fickle as the voters this time around. When Hart is winning, they're up. When he's losing, they blow pig whistles and complain that this campaign is as bubbly as Perrier, and that's the trouble with it— there's not a drunk on the plane. Kathy Bushkin, the only press secretary believed to walk on water, and her clones, with their shining hair, un-made-up faces, perfect manners, and indefatigable fairness, patrol the aisle like school monitors.

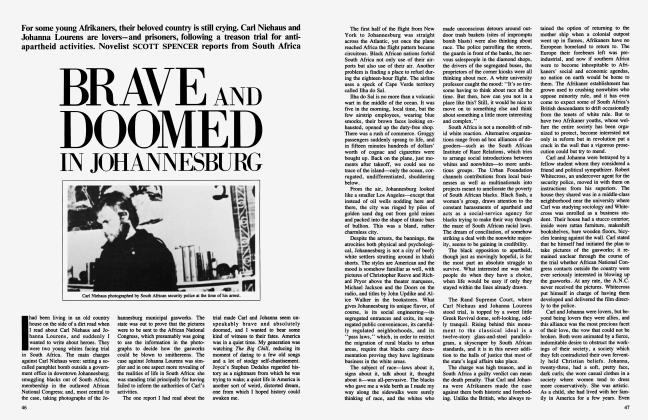

Gary Hart comes walking back to the press section, his cinematic good looks only slightly bruised by the months of being pumped with pneumatic airline food, the regimen of five or six hours of sleep, half a dozen speeches a day, the absence of exercise, fun, or more than an hour to call his own. His usually ruddy skin is gravelly. Both he and his wife are sick with honking bronchitis. They are the first couple to aspire to the White House with a marriage that resembles the rest of America's marriages—up and down—and everybody knows about it. Yet here is a political couple, for once, that doesn't try to disguise it under glazed smiles or tippling or pills. The strain of the campaign shows in Lee Hart, in the grooves of fatigue around her mouth, the weedy hair. Hoarse and fidgety, she can't stop trying to please. Gary Hart, alone, appears above it all.

He stands in the aisle with high-spirited stoicism, not a wrinkle in his fitted western shirt; the only sign of wear and tear is in the run-down heels of his cowboy boots. He is as controlled physically as he is emotionally. (And he doesn't have a shirt carrier as Bobby Kennedy did; he simply doesn't sweat.) He is talking about what he's going to do with his first day off since New Year's.

"What I do to relax is browse a bookstore for half an hour," he says. "I'm working on three books right now, two Kennedy books and a mystery, but not making much headway." He works on everything, even relaxation. What the reporters want to hear is that he plans to ride bareback or swing an ax—something more, well, Marlboro Mannish. But Gary Hart is not a physical man. He plans, in fact, to shop. For what? "The silly little things you run out of," he says, "like a pocket penknife I use all the time." A reporter offers his penknife to Hart, all of a seventy-nine-cent cigar-store item. "Oh no, I couldn't take yours."

I pass on to him a message from Marilyn Youngbird. "Marilyn says you should take time for a spiritual-healing ceremony."

"Do you know Marilyn?" His voice is suddenly buoyant, spontaneous. "She's been my spiritual adviser for the last few years. She introduced me to Indian religion. She's a full-blooded American Indian. Marilyn's given me eagle feathers and, well"—an embarrassed smile catches up with his ebullience—"other religious artifacts."

"A prayer robe?"

"Yes, a beautiful robe." He describes in detail the brilliant reds and blues in the robe Marilyn and her daughter made for him. He was meant to wear it in his role as a peacemaker who would take under it all four colors of man. It hangs on the wall of his Senate office. He also sculpts eagles, the creature Indians believe to be closest to God. "Marilyn's been telling me for a long time I need a spiritual purification," he says. "I'm carrying a note from her in my pocket right now."

It's not to your benefit to win them all. It's okay to have a setback, it keeps your feet on the ground. But you need to take time for you. Get away from everybody. Go to nature. Hug a tree. Come and say prayers with me. Nobody needs to know. It's between you and the Great Spirit.

This is the nature of the notes Marilyn Youngbird often writes to Gary Hart. From 1978 to 1980, she was perhaps his closest friend, a soul mate. They first met in 1974, when Hart's term as a senator was a day old. He got together with Colorado Indians and announced he wanted to help them. Marilyn became his source on educational and environmental matters; he became her political mentor. "What kind of changes do you see?" he would ask her. "How are your children growing up?"

A radiant divorcee, a grandmother three times over though she looks no more than thirty, Marilyn gradually discovered that Hart shared with her a reverence for the sun, the trees, all forms of life. "That's how we became close," she said. "It was in his heart, dormant, but when we started, it came alive." Five years after they met, there was one great moment at an Indian ceremony which brought them close both personally and spiritually.

Marilyn Youngbird told me, "I'm his conscience," and she laughed. But he is, to her, no laughing matter. Her parents are both medicine people. They have all heard the prophecy. The Great Spirit, their god, has chosen Gary Hart to save nature from destruction and to unite all the people. It is time. It is his time.

"I know," he says on hearing the prophecy repeated. "She keeps telling me that."

"Do you believe it?"

"Yes."

A bonfire has been set. The timbers are pointed at the night sky, flaming fingers of prayer trying to get in tune with the Great Spirit. A demonic wind off the Rockies plays across the flat plain and tears at the fire until it lashes out in all directions. They have come here to pray for him—Wallace Black Elk and Grace Spotted Eagle, who are medicine people, a dozen others of red, white, and black skins, and Marilyn Youngbird. But not Hart.

To pray with the Indians, you must take off your clothes and shed your public mask and get down on your knees to crawl into the sacred circle. The fire represents the heart, and the heart must be open. Behind the fire, in a space unbroken except for bare trees with wind-gouged roots, stands the purification lodge. It is a simple hump of tarpaulin stretched over willow saplings. Inside, sitting in the darkness close to others, with time suspended and only the most natural of materials—stones, fire, water, and herbs—you go back to the beginnings of things. They have prayed here for Gary Hart many times.

The first time was five years ago. The medicine people began with a frightening prophecy. Too many people were taking nature for granted, killing it, they said. Nature had already turned on us. Tornadoes, mountains blowing their tops off, all the heavy snows and rains, these were absolute signs of the anger. If we didn't step forward and take control of what was happening, mankind would destroy itself. Marilyn asked who the leader would be. The medicine people asked the Great Spirit. The description that came back—"a man who loves human life and all life, who is spiritually a native person"—fitted the man she knew as Gary Hart.

She gave Gary Hart every word of the prophecy. "They said this man will bring peace to the world. The Great Spirit is saying it's time. The time is now." They talked about his becoming the president. He laughed at first, she remembered. But a year later Hart made the decision. "I felt it would be good for me to move to Washington and help," Marilyn said, and did so in 1980. She later went to work for Senator Peter Domenici of New Mexico. But by November 1983, Hart's long march had begun to look like the Ho Chi Minh Trail of American politics. Marilyn sponsored another ceremony, this time to pray that he become known. It started to happen. On February 10 of this year, a crucial time, she SDonsored a third ceremony, specifically to pray for him in the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. The message that came back was "The thunder spirits are with him. He will take second place in Iowa, first in New Hampshire." Overjoyed, Marilyn flew back to Washington and cornered Oliver "Pudge" Henkel, Hart's campaign manager. "Oh, Marilyn, don't I wish," he said. "Pudge, look at me," Marilyn insisted. "We are going to win. Tell him. Say it." He said the words. To Native Americans, the words are prayers. One must never say "if."

A radiant divorcée, Marilyn gradually discovered that Gary shared with her a reverence for the sun, the trees, all forms of life

On a bone-cold Sunday afternoon in Nashua, New Hampshire, two days before the primary, a petite woman with candle-glow skin stood outdoors in a red sweater, waiting for Hart. She was hatless. A mean wind whipped the silky shoulder-length black hair across her face, but she kept smiling her knowing child-woman smile. The ground was as bleak as funeral dirt, but it would definitely snow in time for the primary, she knew it would. That's how the thunder spirits would fix the primary for him. Only two people in the world believed that Gary Hart would win here: Gary Hart and his spiritual adviser.

Six hundred people had jammed into the center for the elderly, and dozens more had spilled outside, animated by polls that showed for the first time that Hart was gaining on front-runner Mondale. The woman in red waited forty-five minutes, a face in the crowd. When his car pulled up, a crush of people flew out to cheer and cameras chewed film and Garv Hart looked stunned, even scared, she thought. He found her face.

"We need to get together," he said to her. "I need to talk to you."

On leaving, this shy, aloof man did something completely out of his public character. He sought out Marilyn and gave her a hug and a kiss on the cheek. "Whatever you're doing," he said, "keep doing it; it's working."

But he never did get together with her. Marilyn flew back to Washington before midnight and the victory party.

"I figure the day will come," she explained to me. "I don't feel rejected like some of the others. I just keep working hard and praying."

For this ceremony, midway through the campaign, she has come to ask the medicine people what happened: Why hasn't the momentum continued?

"Tell Gary everything's ready," she informed his Denver press secretary, Tom Gleason. She insisted that Gary make the decision himself. He sent a message: "I need to go, but I don't have time."

Marilyn explains the purpose of the medicine-lodge ceremony. "If you pray, and it comes from your heart, you get a message. Going to the sweat lodge is the way we rejuvenate our health and keep ourselves on the right road of life. It's a cleansing of the body and the spirit. Gary knows he's supposed to do it, but he hasn't had the time... "

Even as she makes excuses for him, she is troubled. "At the beginning," she says softly, "he was dedicated. He was in prayer too. But once our desires were granted and he became known, swept up by fame, he didn't continue with his prayers. He forgot his original ideas. He lost his spiritual foothold."

"Miiakuye obwanikfacha" ("All my relatives"), whispers each participant on entering. They wear sarongs of toweling or sheeting. Even the bodies heavy with age or sickness, silhouetted in the moonlight as they crawl through the opening, become natural, beautiful.

It is difficult to imagine Gary Hart in this setting, dragging with him vestiges of the dark evangelical beliefs of the Church of the Nazarene drilled into him by his mother: that man is born with a sinful nature, that natural functions and appetites must "continue to be controlled" by "putting to death the deeds of the body." The tent flap opens and the moonlight lays a path to men's legs, naked and muscular and working, as they lift lava stones out of the fire and push them into our circle on pitchforks. Seven sacred stones are lowered, one by one, into a pit. Each fiery stone dances with star bursts like a rekindled meteorite, brought in with its own sun and moons. Sage and cedar are cast onto their surfaces, and their piercing scents rattle the memory at its deepest reserve. Water hisses. The flap is dropped. Heat crushes the head. "The harder the obstacles ahead, the more painful it will be," whispers Marilyn. Moaning, rocking, the group sings louder. A cowhide drum pounds at the heart.

"Ho!" shouts the medicine man. "Ho!'*' respond the others. Spontaneously, they offer the tenderest confessions, the humblest prayers. Marilyn prays long and hard for Gary to find his way. Meanwhile, the medicine people pray for Jesse Jackson, whom they seem to like better. There are moans of relief, swoons of replenished hope as toxins pour from the body. Time drifts. I have no idea we have been here for six hours when Wallace Black Elk delivers the prophecy Marilyn has been waiting for. He speaks of the Hart that is not there:

"He strayed off his spiritual path. He started floating. Now he has come home to the West, he can regain his footing. He must wear his robe and gather all four colors of man under it—black, white, yellow, and red. The West will hand him a great gift. But he must contend with it."

An image appears on one of the sacred stones. It is an eagle.

There is in Gary Hart an enormous and unarticulated passion about the issues, about life in general. It is the unrealized passion of a person who is not yet able fully to express himself. —A longtime Hart associate

There were three seats across on the plane. I sat in the one next to him. He shrank back to the window, clearly commanding with body language, "Don't come close." I moved to put a seat between us.

When we had talked for a while, I told Gary Hart about having been with Marilyn Youngbird at the spiritual ceremony. His whole demeanor changed. His voice became tender, his body language less defensive.

"I'm fascinated by Indian religion," he said, "not in an academic sense, in a personal sense. I like the pantheistic aspects of it. I think there is something spiritual about nature. When we treat nature poorly, we are treating God's creation poorly."

What was his conception of God while he was still a believer in the Church of the Nazarene? I inquired.

"God was a person. He had gray hair."

"Was He punitive?"

"Yeah, if you did bad." He laughed. "He was a God of mercy, but of wrath as well."

He accepted the belief that history would end cataclysmically. He still maintains an important part of that doctrine.

"I believe in life after death, oh, sure, absolutely," he said quickly. "I reaffirm it all the time. My more sophisticated assessment flows from observing the creative spirit. Composers, writers, poets—that spirit cannot die. It's too powerful."

What about the ordinary person who has no creative genius? I asked. He came back with the definitive midwestem egalitarian view of life.

"There is no ordinary person."

The dominant climate of Hart's childhood was at war with naturalness. He admits, "The one Protestant quality I suppose I've got my share of is guilt." Yet, strangely, the Indian ritual was not so far off from the process dictated by the Church of the Nazarene, the purpose of which is to "receive the cleansing of our hearts by the incoming presence of the Holy Spirit. With this cleansing comes an empowerment to live a victorious life and to serve God effectively. There is no longer the inner conflict of a divided heart."

Gary Hart seems to have transcended the narrow, doctrinal way in which the religious values of his boyhood were expressed. He loves all life. If there is a single theme running through his public-policy views—control of nuclear arms, a demilitarized foreign policy, putting people back to work through American ingenuity, educating our children to inherit the future wisely—that theme would be the protection and celebration of life.

"What drives you?" I asked. "Is it still a ministerial dictate, but you're working it out in a secular pulpit?"

"I can't explain it rationally," he said. ''It's just a sense that for part of my life—not all of my life—I want to make some contribution. I was given some political talents. It's quite accidental. There's nothing in the genes to account for it." He paused, introspective. "I'm not always comfortable using them. I wasn't given the personality to go with them."

One of the few personality characteristics that are strongly influenced by heredity is social style. Gary Hart may have been born an introvert. His early upbringing certainly would have reinforced it.

"Was your mother demonstrative?" I asked.

"Not really."

I had been warned repeatedly not to ask the next question.

"Did she hug you?"

Warily, "Did she what? Oh, yeah. But not demonstrative in a loud way."

I asked about his first memory of Ottawa, Kansas.

"Very cold," he blurted. "I remember one cold winter day—Dad wasn't there. I came downstairs. I was about five. I put on an old coat sweater hanging from a hook and a mouse ran out of the sleeve. My mother screamed. I remember that vividly."

Hart had been stung by reports that his Irish mother was "reclusive" and "eccentric." He told me she was always exhausted. She had an overworked heart. No one knew her exhaustion stemmed from a malfunctioning thyroid gland, not until she'd had enough coronaries to be taken to Kansas City for a proper diagnosis. His father drifted from job to job.

"A lot of people, like Nixon, who come from an impoverished cultural background, can never overcome it. Gary has"

The only refuge the boy found from the cold, from the frozen dogma of a bleak church, from the instability of moving all the time, was in books. "I went through a cowboy phase and read all of Zane Grey, then I got off on science fiction. I loved to go up to Kansas City 'visiting.' All I'd do is sit and read the magazines. My family was too poor to afford magazines."

At each major point in his adult life, Hart has demonstrated boldness in breaking out of old molds. It began at eighteen, when he pulled up roots.

"I was the person who broke him," says Prescott Johnson, his old philosophy professor, a twinkly-eyed Midwesterner with center-parted hair whose benign mischief in life was to loosen up boys bound by the Bible. Johnson was impressed by Hart's College Board scores: all in the high-90 percentiles.

"What I wanted to do with Gary was to temper his strict religious upbringing with intellectual interpretation." And so, no sooner had Hart begun at the fundamentalist Bethany Nazarene College, just over three hundred miles from his home, than Johnson took his protege through Plato, Socrates, metaphysics, and existentialism. When they came to the Grand Inquisitor's speech in Dostoyevsky, "Gary saw that the church had transgressed the essential Christian message." Johnson later left the church, as did Hart.

But Johnson had given Hart another gift, the first sanction and sanctuary to spend time alone with a woman. Gary and Lee Ludwig used to baby-sit together for the Johnsons. Lee was of another social stratum, what they called "a city gal," coming from Kansas City, with a father who was "high up" in the church as well as a former president of the college. "She was always pretty," says Johnson.

Recently, when they met up in Iowa, Hart told his old professor, "Prescott, my ideas are blueprints." Not molds or ideology or even party lines. One can't tell how they would work, how they'd have to be modified, until faced with the actual problems. "But he can't say that to the public," adds Johnson. This doesn't worry the professor; he believes that Hart has the conceptual ability and flexibility to think his way through any problem. And Hart surrounds himself with smart people. "A lot of people, like Nixon, who come from an impoverished cultural background, can never overcome it. Gary has. He's definitely inner-directed. This thing about Gary being just a cold intellect is nonsense. He's got compassion and feeling. He just doesn't wear it on his sleeve, see?"

Johnson wanted me to ask Hart what sphere of existence he is in now: aesthetic man, not committed, symbolized by the sexual profligate; moral man, defining himself by the conventions of society, symbolized by marriage; or religious man, who finds a new immediacy in his relationship with God.

"I think moral," Hart replied, "headed toward religious."

Hart was a transient in his twenties, always maintaining a "flexible base," never committing himself. Emotionally he was also changeable: "I almost quit doing anything when J.F.K. was killed." Bobby Kennedy's murder kept him out of action for three days.

A deliberate remaking of identity began as Gary Hart started law school. He went to court to change his family's surname from Hartpence to Hart. "Nazarene" was not included in his college's name in his official biography. Later, he would change his obscure script to block letters, a style of writing that has the effect of concealment.

The turning point came at thirty-two, when he left a brass-plated law firm and struck out on his own. He had put down new roots in Denver only two years before. Working out of a basement rented to him by Richard Lamm (later to become Colorado's governor), Hart was often taken for the janitor. His driving ambition was to direct the enterprise of his own life.

The element of risk runs all through Gary Hart's choices, not only in following his convictions but in putting all his material security on the line. "If you were going to build any kind of economic security for your wife or kids, you would have made all those decisions differently," says Lamm. ''Gary rolls very high dice."

In 1972, when he was thirty-five, his mother and father died and his political forebear, George McGovern, was buried in the primaries. I asked Hart if it was a crossroads for him.

''I'm sure it was, but I haven't reflected on it," he said. ''Not enough to articulate it. My mother died just before the New Hampshire primary and my father died the night of the New York primary. It was a very bad year."

Did he do any grieving? Hart said yes—''but I wouldn't quit." Strong attachments were formed while he was managing the McGovern campaign, attachments that transcended the political disaster. "Had I left when things went bad, it would have looked like I was cutting and running."

Harold Himmelman, a Washington lawyer, remembers vividly how Hart handled that failure. Himmelman stopped by Hart's rented house in Washington to tell him good-bye before Hart went back to Colorado.

"Everything was over for him. He was a shattered man. Gary had nothing—no career, no money, no future. He was then the architect of the world's worst political campaign ever run. I was close to him. We shook hands and looked at each other, and never said a word."

Hart's ability to rebound from failure is remarkable. Stoic, he shuts himself off from the volatile emotions around him and tells himself to vault back. He is never comfortable for long with allowing spontaneous feelings or suspending full control. Yet, on the inside, he is always changing—a protean man. No one I talked to knew all of his shapes. Not even his wife.

Lee Hart was a classic helpmeet-style wife. While Gary Hart's exit route from a narrow midwestern upbringing was intellectual, Lee Hart's aspirations were material. She was destined to be frustrated. From Nazarene, she and Gary drove a jalopy east to Yale, where Gary entered the divinity school, never with the concrete goal of becoming a minister. Lee began supporting them as a teacher earning $4,000 a year. They had a grocery budget of ten dollars a week. Six years later, while Gary was finishing law school, with no concrete goal of becoming a practicing lawyer, she was making only $5,200. Lee quit in 1964 to have her first child and didn't go back to a job until 1979, when she and her husband first separated. They reconciled after six months, and she campaigned for his Senate re-election. In October 1981, Hart's office announced a divorce. Lee Hart tried her hand at real estate. But if there is anything harder than campaigning ten hours a day with one's husband, she told me, it is competing eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, with the real-estate sharks around the Potomac. The Harts were reconciled again shortly before Gary began his presidential campaign.

When I asked Lee Hart about her husband's indifference to material things, it was obvious that I had touched a raw nerve. "Sure, I'd like to have the freedom that money can bring," she conceded. "I'd love not to have to worry how we're going to pay for our children's college educations, but so would everybody else. I can't go to Colorado and ski like I'd like to, because I can't afford to. I can't go to New York for a weekend and take in a play, as I would love to, because I can't afford to."

Gary's being tagged with the Yuppie label is an irony not lost on Lee. If anything, Gary Hart is downwardly mobile. He had a negative net worth in the year he worked as manager of the McGovern campaign. His balance sheet would still be a disaster if he hadn't hit it lucky in buying a house in Washington in 1975. But last winter he took out a second mortgage against that house to make media buys in New Hampshire.

At forty-eight, still earnest, Lee Hart on campaign bounces down lines of motorcade cops with her long windblown hair and cheerleader smile, and though some of the fullness of her cheeks has fallen away, she projects warmth. She tries to edge onto the armrest next to her husband on the campaign plane. He ignores her. She struggles to lift the armrest and back her hip close to his. He is oblivious, talking issues with the press. During joint campaign appearances she comes forward, on cue, acknowledged by her husband only for her hard work as "already deserving the job of First Lady." He never touches her. She holds up her hands like the trapeze lady in the Flying Wallenda family, then drops back into obscurity. Not infrequently, Hart forgets to introduce her altogether. At other times he has been quoted as saying, "I have almost no private life."

Does she think of Gary's bid for the presidency as preaching in a different pulpit?

"Well, I will not speak for Gary. I can't. But I've always felt there is a great deal of similarity between the kind of background that I came up in, service-oriented in the church, and politics."

"Would you say that what really drives him is not ambition or power but that old inner dictate to do good in the world?" I asked.

"Yes, that would be my feeling."

As Gary Hart moved into his forties, however, things began to change, loosen up. He appeared hungry to make up for some of the boyhood adventure he had been denied.

Odd, many people thought, that a man would go out of his way to get a naval commission at the age of forty-four. Between the wars, Hart had had a student deferment from the draft. But he'd met Arizona representative John McCain on a trip to China in 1979. A navy pilot shot down in Vietnam, McCain had survived several years of assaults to his body and brain as a P.O.W. and returned whole. Hart idolized him. They helled around together.

McCain told Hart, "You gotta touch metal" before you can talk military reform intelligently. A senior staff member managed to persuade Hart during his re-election campaign, in 1980, that to seek an anachronistic military commission would look as if he were playing catch-up P.T. boat. Hart waited. His desire had a deep but unarticulated connection to his fourteen-year-old son and concern about a war in the Persian Gulf. But there was also a naive romanticism that drove him to go through with the application, and to spend two weeks on a battleship. One associate believes "he really wanted to be John McCain."

It wouldn't be surprising. In high school he'd had a crush on an usherette, but his church forbade moviegoing. He implored his schoolmates to give him blow-by-blow descriptions of the movies they saw, and he hung on every word. It established a pattern of vicarious experience that seems to have been played out repeatedly in his adult life.

Hart today enjoys talking about spies and their connections with the Mafia and Cuban exiles. He loves the inside dope, loves hanging around extroverts who do live on the wild side. Yet he himself has remained a man not of action but of intellection.

In his personal world, Hart's driven-to-do-good side would be suspended suddenly for a spate of living it up.

The first mention of distance between Hart and his wife appeared in the Washington Post back in 1972. Hart would offer only, "I believe in reform marriage." After the article appeared, he retreated into total secrecy about his private life.

Gently, Marilyn Youngbird kept encouraging him to go with her to an Indian ceremony. Finally he said he wanted to learn. In July 1979, the Comanches from Oklahoma went to Denver to hold a powwow. Hart was about to separate from his wife for the first time.

"So, early one morning we went to a sunrise ceremony," Marilyn remembers, her voice becoming more and more ethereal as she tells the story. The sun had chinned the horizon by the time they arrived at the large park. They heard chanting and felt the rattle of gourds over a slow beat of drums. In the distance, a haze of scarlet and blue snaked against the pale sky. As they drew closer, they saw that the haze was brilliant prayer shawls draped over the backs of the gourd dancers. Their senses quickened.

"It was so romantic. So beautiful. It was like poetry," she says.

"They brushed the front and back of our bodies with eagle feathers. It was sensual, oh yes. He would look at me, smiling from ear to ear. Then all the smoke from the sage and cedar would engulf him. We didn't know whether to laugh or cry, it was so beautiful. It was one of the biggest honors for the Comanches, that a Colorado senator would take the time to stand in this line with their society, extend his hand, accept their way. It was an enormously powerful moment. Then they prayed for us. That our way in life would not be the selfish way, that we would not be taken in by greed or hatred, that by extending ourselves we would be guided on the sacred way."

When they had finished praying, she says, Gary Hart reached out and touched the prayer shawl of a medicine man. It was, it seems, a peak moment.

Another pattern has played itself out again and again. No sooner does Gary Hart's natural and loving side enjoy a brief outburst than alarm bells go off and some inner steel door clangs shut. He appears to deny that side ever existed. "I think there is some deep appetite within Gary to hold on to ultimate control," says a former associate.

Genuine political liabilities result from this personality pattern. Because Hart cannot express his passion, he cannot make voters believe he feels what they feel.

There are only a few people in Hart's life who draw him in the direction of his heart, the three women he allows close—Marilyn, his daughter, Andrea, and his press secretary, Kathy Bushkin. They all share traditional female qualities: they are comforting, never critical, utterly constant. His aides put Andrea in the room with him before a debate because he can laugh with her. Kathy Bushkin spends half her time on the campaign plane hanging over Gary's seat, reading his every mood and need, a hovering angel with her tiny frame, angel hair, and pearly skin. With Marilyn Youngbird, around the time of his first marital separation, he could admit some vulnerabilities, concede that he was still forming, not complete.

But once Hart officially separated from his wife, that steel door clanged down on his natural side. "I think he carried a real heavy sorrow," Marilyn says sympathetically. "More than he did when they were together. He loves his children very much. I think he loves Lee. He was downright miserable. We never talked about it. It was too personal for him. But that was what I saw in his face."

Marilyn is now engaged and sees Hart infrequently, although there is a continual flow of communication. She considers him important in her life and crucial to the country. Gary Hart may have relegated her to a symbolic role in his life, but her spirit is still powerfully with him—in the notes riding around in his pocket, in the prayer robe hanging on his wall, in the face he searches for in a campaign crowd.

While he was officially seeking a divorce, Hart went through two other important and ultimately poignant relationships. One was with Diana Phipps, a professional English hostess, to whom he said, "My God, you European women are so charming." The other was with Lynn Cutler, an elegant widow and a dazzling figure in Iowa state politics, whom he wooed romantically and politically. Both felt that steel door clang shut. "The effect can be brutal," says an associate close to Hart.

Hart's campaign was always meant to be unconventional.

While Marilyn Youngbird was nourishing his soul, Larry K. Smith went to work on shaping the vision in Hart's mind. An arms-control analyst and former Dartmouth history professor, Smith was Hart's chief of staff when the senator's name surfaced in 1979 in the gossip market of presidential mentions.

In late 1980 they began their systematic planning of four pillars, or "idea clusters," on which Hart could rest his ideas. Their premises were that the Democratic Party was essentially a power vacuum, and most other candidates, particularly Mondale, did not have the capacity to sum themselves up. Mondale's concentration was always politics first, policy later. Hart would reverse the process. He would raise no money, hire no political staff, eschew special-interest money, and instead concentrate on developing unconventional ways of thinking about four policy areas in which he had already invested effort—military reform, arms control, industrial policy, and energy independence. The idea was to demonstrate that he could "outthink" any problem.

Stage Two of Smith's grand design called for finding "crosscuts," which could integrate these otherwise fragmented policy areas into thematic speeches. He hoped to find a half-dozen pungent phrases or parables to crystallize their ideas. In Stage Three, he and Hart would design the "delivery system"—that is, campaign organization. But in 1982, Smith decided to leave Washington to be with his family before his teenage children left home.

The key people Hart had counted on for support and closeness, though he hadn't acknowledged it, were no longer active when he went into high gear as a presidential candidate. He and his wife were reconciled and set out to campaign together.

His chief of staff knew all along that the name problem and an age discrepancy were dynamite waiting to explode.

All through grammar and high schools, Gary was called "Hotpants." "A blemish like that can become larger and larger in a young person's self-image, like a mole or small breasts, so that you can't go on until it is repaired," offered Senator Christopher Dodd, which took the curse off the issue in Dodd's state of Connecticut and helped Hart to a big win there. But when the question was put to Hart in public, he choked.

On February 25, Lesley Stahl prepared her usual ten questions for a ten-minute guest slot on Face the Nation the next day; two, she thought, would be throwaways.

"There's a mini-issue. . .bubbling ... under the surface around your campaign," Stahl began, almost apologetically. "It really, you know—there's no stigma to it, but why did you change your name?"

A minute later Hart was still stuttering, "No, that—well, I, I don't want to get into a quarrel with my uncle, but... "

"Also, there's a question about your age."

Defensively: "I am exactly the same age as my birth record, which is 1936."

"There's never been a discrepancy?" The throwaways had by now eaten up almost four minutes.

"Well, I—no, I can't account for every piece of paper that's been written by my campaign..."

Dotty Lynch, Hart's pollster, observed that when he doesn't feel loved he pulls back, becomes icy and wooden, needs to reassert control.

Professional actors, in the same game as our sitting president, came to observe Gary Hart at a private Hollywood party at producer John Foreman's home.

"What's your favorite ice cream?" was the last question. "Haagen-Dazs," Hart uttered through clenched teeth, "chocolate chip." I asked Jack Nicholson what he thought of Hart's talk. He gave his homicidal lid flicker, said "He's doin' a lot better," and drove off in a limo-length Mercedes. Rock Hudson sat looking phlegmatic. Peter Falk had asked Hart how he would negotiate with the Russians. Seeming to forget strategies he had stated strongly elsewhere, Hart fell back on the "walk in the woods." Falk said later, "Rock's like me, neutral, not convinced." Margaux Hemingway shrugged: "No adventure or excitement."

Larry Smith watched the campaign from the distance of a professorship at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He wrestled with guilt as he saw the pillars of Hart's grand themes crumbling and unconnected ideas being recast into stilted speeches on industrial policy or foreign policy. He shuddered as Hart's Children's Crusade of a campaign organization came under fire from Mondale's professional juggernaut.

Those who stayed with the Hart campaign worked out of love, many young people giving up a year or more of their lives. By January of this year, things were so dreary that Hart began to question his conviction that it was his destiny to become president in 1984.

One old associate says affectionately, "What I wanted for my friend out of the whole catharsis of the campaign was that he realize himself. He came close this January, I think, to the self-understanding that he had depended on other people to do something very difficult with him, and that he himself was limited and still capable of growth."

New Hampshire, even as it affirmed his long march, may have interrupted the process of inner development. The crucial two weeks for Gary Hart's campaign were bracketed by the New York and Pennsylvania primaries, and that is when he lost it. He lost the generational message and the substance of his new ideas. He became susceptible to other people's ideas.

In New York he let three congressmen from heavily Jewish districts in Southern California—Mel Levine, Howard Berman, and Henry Waxman—who jumped in to endorse him, convince him that the move of the American Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem was a "litmus test" for the Jewish vote.

Hart switched positions in midair. Just as the voters were trying to get a fix on Gary Hart, he showed them inconsistency. He lost the appealing veil of his "outsideness." He never was going to get Establishment Jewish leaders, and in the attempt he lost support everywhere else.

The question for the future is: Can Gary Hart complete himself in time for the next election? Does he care to? Will he lose interest in politics before that happens? The phrase he used in a Today-show interview with Mary Nissenson was "I'm doing politics now." During a bull session on the campaign plane he bemoaned the lack of moral courage in our society today. I asked how many moments of courage he'd seen in his ten years in the Senate. He thought awhile.

"Three."

His advisers, who had picked a long shot, look ahead to 1988. Hart's own commitment may be more ambivalent. When he looks at 1988, he sees a field crowded with attractive New Generation Democrats—New York's Governor Mario Cuomo, North Carolina's Governor Jim Hunt, Senator Bill Bradley of New Jersey, Senator Dodd, Representative Albert Gore of Tennessee, Ohio's Governor Richard Celeste, and more. Hart might be just a face in the crowd. Which was why he went all out for 1984 in the first place.

But he also has a side bet. "My fiction writing turns out to be pretty good," he told me. "They [his publisher, William Morrow] said, uh, that I was, you know, good enough to do it, professionally."

He is a risk taker, an anticipator; he has an exceptional sense of timing. He maintains that he is better than many at out-waiting the political tides. His overall theory of politics is that pressure builds for an innovator, a new leader is chosen who is not ideological but experimental, he tries new things, some of them work, and along come the followers, who institutionalize those things that were once experimental. They become dogma. Then times change. The dogma doesn't work anymore, and the process begins all over again.

What he ran up against in 1984 suggests that people are not quite ready to begin again. "People are not doing well," he said, "but they're not flat on their backs. So they're not so desperate to roll the dice."

There is, of course, a symbiotic relationship between a great leader and the society that creates him or her. The new protean men and women sense intuitively that they are working with a different human prospect. The will to dominant world power and the expectation of unlimited progress have run into limits unimaginable to many members of Walter Mondale's World War II generation or those of Ronald Reagan's era. Hart and Reagan have read the same biblical prophets, but their responses could not be more dramatically different.

Reagan, an old man aware that his health could deteriorate suddenly, has a perspective on the future overshadowed by mortality. At least five times in the past four years Reagan has spoken of his vision of Armageddon coming "very fast." Gary Hart is just as determined not to be forced into conflict. He believes in trying every avenue—economic cooperation, diplomacy, human aid —to help alleviate poverty and humanrights abuses, anything to avoid escalating what Emerson would have called the "epidemic insanity" of the arms race.

But has Gary Hart got it in him to be a leader?

Many people would rather risk even death than change. That is what makes Hart so different. He thrives on change. The very process of testing the less traveled path, as Hart has been doing, allows an accelerated inward development of personality. But along the way the potential leader usually loses his footing in the new darkness. There is a withdrawal, then a personal, creative act of transfiguration. That completed, the person returns, confident of his inner consistency, to inspire the society to risk transformation. This would be the prayer of some of those closest to Gary Hart.

He himself sounds the right note of urgency. "Sooner or later, the country is going to have to move where I think we should go. The thing I don't know— and I think about it all the time—is whether people can perceive what has to be done, when there's no crisis. Our history is otherwise. But we're skating on thin ice right now. We have to change and fix things or we're dead."

In many ways, Gary Hart is emblematic of his generation. Tagged the Silent Generation, its members came of age in untested times—too late for World War II, too early for Vietnam, a little too old to be swept up in the sexual revolution or drugs or nihilism of the yeasty sixties. But many cared too much not to be involved. Renamed the Kennedy Generation, it was their fate to be perpetually in the middle, the mediators between their Depression-raised parents and dropout younger brothers and sisters. Never the agents of change, they have only paved the way to, or picked up the pieces after, change. Perhaps Hart is the closest they will come to taking command. In the cycles of political change, Gary Hart will probably be the transitional man.

On April 29, Gary Hart was scheduled to be received by the Comanche Indians in Oklahoma City. They were to bless him with eagle feathers and give him another prayer robe, as a reminder. Marilyn Youngbird had initiated the whole ceremony.

Delores Two Hatchet called Marilyn that night, despondent. Two tornadoes had hit with random fury during the day. Dust was blown so far, the cars in Ohio were covered with a thin layer of Oklahoma. Hart ordered his pilot to land anyway, but the airport was closed. It was one more spiritual touching that Hart would miss.

Marilyn said it must be the thunder spirits protecting Gary.

Tornadoes are one of nature's last remaining mysteries. This past spring the violent funnels were greater in number and ferocity than ever before. That day gave Marilyn Youngbird an eerie feeling. Could it be the thunder spirits telling us our time is up? Nevertheless, she reaffirmed her faith.

"Gary already has one robe. He just has to accept it, spiritually. Then he wouldn't have any doubt. He does have new ideas. They're coming. They'll come."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now