Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn Vietnam We Were All Victims

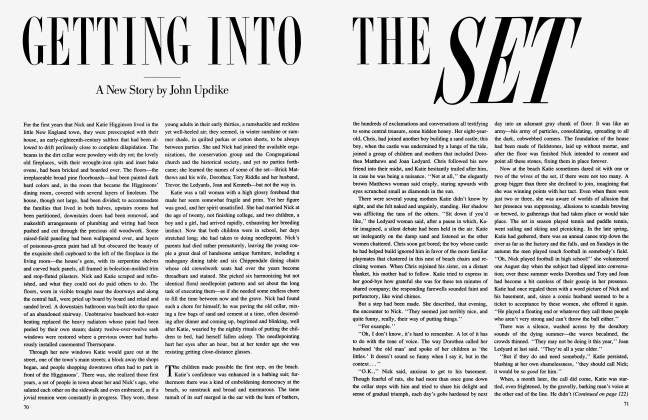

Garry Wills

John F. Kennedy felt that not being a veteran was enough to disqualify Hubert Humphrey and Nelson Rockefeller for higher public office. Today that criterion, if invoked at all, would work in reverse—which seems not only unfair but an abrupt departure from our traditional attitude. Yet the idea that we have always honored our veterans is one of many myths bequeathed us by World War II; and that myth would have struggled to a difficult birth if World War II veterans had dared to say in print, in the 1940s, what they tell Studs Terkel in his new book, "The Good War": An Oral History of World War Two.

Vietnam did not differ from other wars in being cruel, inhumane, or racist. It did not differ entirely in being a defeat—we lost more in our past wars, including World War II, than we were ever allowed to learn. Then why have Vietnam veterans been treated, even by comparison with our past equivocal record, so shabbily?

One way of answering is to say that Vietnam is the first war about which a book like Joe Klein's could be written. I do not refer simply to the fact that in Payback: Five Marines After Vietnam (Knopf) Klein does not have to fudge, as Norman Mailer did in The Naked and the Dead, when using the brutal language of war. That fact is symbolic of an entire range of candors expected, not merely accepted, by Klein and by his readers and by the five Vietnam veterans whose lives he traces in such intimate detail.

The conditions that made for such candor changed, of necessity, the very nature of the war. War is waged around the compact of a society's dirty little secrets—its racism, its greed, its calculation of loss in the expendable parts of its populace. The racism that caused the percentage of black casualties in Vietnam to amount to nearly twice the percentage of blacks in our population in 1965 was no longer a secret. The Pentagon itself had to react. Fraggings occurred in other wars, but were covered up. In Vietnam we learned that the conditions making it hard to cover such things up make it harder, as well, to prevent them.

I run ahead of the "simple" facts of Klein's book, partly to hurry people through the psychic barriers that fended me off at first: "Oh no, not another Vietnam-vet-flipping-out story. And didn't it have to be about a person called, improbably, undeniably, Gary Cooper, who went conveniently berserk when the papers could note the irony that the hostages from Iran were being feted as the veterans never were."

Well, Klein asked for it by starting with that item about Cooper from the papers. But what he gives us besides breaks mold after mold—first that of the original story he wrote for Rolling Stone, then a whole series of molds that have contained our thinking about Vietnam veterans and about the war itself. The Catch-22 for those returning from our last war is that they did not want to be treated as if military service were a disease they had caught; yet lobbying for their rights has reduced them, often, to arguing that some delayed "effect," or "trauma," or "syndrome," or "disorder' '—a disease by any other name— does afflict them.

Klein shows that the five men he chose to study—though all were hurt deeply by the war—share no one disease, despite the fact that they had shared many experiences, before the war as well as during and after it. The book has a thousand easy generalizations at the tip of the tongue, and lets not a one spill over. The accident of his starting point makes his group no "sample" in any sense—they are all marines who enlisted and served in the same company; all white, three of the five Catholic; all lower-middle-class. Each man entered across a time gap. Born into the Korean era, they held ideas of the military formed by World War II movies on late-night television. And each was wrenched out of that past by the very experience he thought would prolong it. They fled from small towns or neighborhoods to a world where drugs were easily available and accepted, a world through which social change was forcing itself with the insistence of the rock beat that was its symbol.

Custodians of a dissolving culture, they found themselves the unwilling carriers, as well, of that culture's solvents. Some suffered as much from their failure to escape the chaos of change in the sixties as from their brief, disorienting exposure to death and wounds. The war played some part—a different one for each—in the breakup of marriages, in struggles with alcohol, in jobs lost or emptied of meaning. But these are variations on themes familiar to all their contemporaries, who shared the special opportunities and temptations of being American in their time.

The veteran is no doubt right when he says that those who have not experienced war cannot really know what it is like. But Klein supplies the complementary truths: that no human being is reducible to just one set of experiences; that all of us are mysterious because of the separate things we have undergone; yet that we all share overlapping experiences, which reveal us—even to ourselves—only in the light of a respect for the complexity of others. Klein's book is important because it gives us "case studies" without turning up a single case, just five unique people. In the process, he breaks down the idea that Vietnam veterans need some special excuse or vindication because it was their war. It was our war. All its victims are our victims, and are ourselves—all freres, all sembtables.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now