Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

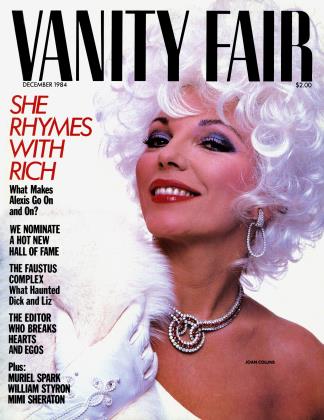

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPRIVATE LIVES

Richard Burton was haunted by Dr. Faustus’s bargain with the devil.

JOHN DAVID MORLEY

Richard Burton slumped in his chair and surveyed the wreckage of the dinner table. All of a sudden he seemed to have become drunk; not by degrees, declining gradually through an evening of Jack Daniel’s, vodka, and tequila, but precipitately and frighteningly, as if he had fallen over a cliff.

Only two of his guests had stayed the course with him. The mild-mannered publicity agent who had flown in from Los Angeles that afternoon to discuss arrangements for the forthcoming Academy Awards sat on his left; and on his right, at the far end of the table, was the young Englishman he had invited to the family home in Puerto Vallarta, in Mexico, as private tutor to the children. The children had slipped away to their rooms, the local guests, rich Americans who wintered in Vallarta, to their homes. Elizabeth Taylor prowled up and down on the other side of the room.

“Dunbar!” exclaimed Richard unexpectedly. “Anybody ever heard of Dunbar?”

“A late medieval Scottish poet,” responded the tutor, adding warily, “but I’ve never read anything he wrote.”

“Not read Dunbar? Well now, David. I can recite him.”

And he could, too. No idle boast. Words that had been written five hundred years ago surfaced astonishingly through the drunken torpor of the mind of a Welsh actor sitting on a balcony overlooking the Pacific, and advanced majestically down the resonant avenues his voice unfurled in the evening air. One stanza, a second, a third. The sun seared the horizon and dipped swiftly into the sea, detonating the sky in a series of gold, pink, and vermilion explosions. And after each stanza, the sun down now, the sonorous Latin refrain of Dunbar’s poem sounded somehow darker with each repetition.

Timor mortis conturbat me! The fear of death anguishes me!

A dozen stanzas, a dozen times the same remorseless, thundering refrain.

Elizabeth put her hands on her husband’s shoulders and said gently, “I think that’s your cue to go to bed.”

Richard got up without a word and allowed himself, stumbling, to be guided up the stairs.

The publicity agent sat motionless in the dark, head in hands, weeping silently. A night breeze crept up off the ocean and ruffled the clusters of shells hanging from the eaves into a sound like the splintering of fine porcelain.

In August 1984 I read on the front page of the International Herald Tribune about the death of Richard Burton, the celebrated actor, in a hospital in Geneva at the age of fifty-eight.

My first reaction on reading the notice of Richard’s death was not a feeling, but an image: the image of a man sitting on a balcony overlooking the Pacific, galvanized out of an alcoholic stupor by an energy only his memory could have generated, as he recited the memento mori verses of Dunbar. For the young tutor from England present on that unforgettable, occasion was myself.

It is fourteen years now since Nevill Coghill, emeritus professor of English literature at Oxford University and an old friend of my family’s, called me up one evening and asked me if I would be interested in a job as private tutor to the children of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

Richard had got to know Nevill at Oxford during the war, and it was Nevill to whom he turned when the education of Elizabeth Taylor’s younger son, his own stepson, became a pressing concern. He was dissatisfied with the education Christopher Wilding was getting in Hawaii, and had presented him with an ultimatum: either a serious boarding school or a private tutor. Christopher opted for the latter. Richard duly wrote to Nevill, asking him to recommend someone. Nevill kindly recommended me.

In February I flew to the Burtons’ home in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, with Christopher Wilding and his cousin Christopher Taylor. Swiss-born polyglot Raymond, Elizabeth’s personal assistant and man Friday seven days a week, met us at the airport and took us on an exhilarating ride by dune buggy to Casa Kimberley.

On the way, the faces of my employers appeared, a yard high and somewhat Hispanicized, on the posters outside the local cinema, billed as Antony and Cleopatra.

The car came to a halt at the top of a narrow cobbled street outside a tall, massive-walled house ablaze with lights. The boys frisked and capered, relishing the scent of home.

And then I became aware of something besides all the capering and backslapping that was going on in the street. Twenty feet above our heads, I saw Richard Burton standing in silence, hands in pockets, scrutinizing us from the balcony of the house.

Why was there no word of welcome from that impassive figure on the balcony? I felt a sudden chill; our tumbling boisterousness in the street seemed foolish and out of place. By the chemistry of a single glance the scene had been entirely transformed. The brooding figure on the balcony was not Richard Burton but Heathcliff; I had arrived not at Casa Kimberley but at Wuthering Heights.

At our first meeting he was courteous but reserved, for the most part quite impenetrable. He shook my hand, invited me to call him Richard, at once offered me a drink and escorted me to the bar. I noted a powerful figure, commanding hands, a swollen, pitted face which at some point in his life had assumed a glaze of expressionlessness and slowly petrified into a mask. It betrayed nothing. But of the presence there was not the slightest doubt; a mysterious emanation, which could both draw people and hold them at a distance. I had felt it across twenty feet of darkness. And then there was the voice. I sampled it over the bar. Not just a voice, amplified by pitch and technique, but a marvel of ventriloquism. Even during small talk, with no more space between us than the length of my arm, he sounded like a man addressing me from the bottom of a well.

It was always unmistakably Richard’s voice which rose up out of that well, but the role in whose service he deployed it was occasionally that of Mark Antony, much more frequently that of Heathcliff, splendid in isolation, not deigning to appear on the set at all.

And what a magnificent set it was, that house overlooking the bay of Puerto Vallarta; a house in two parts, an upper and a lower house, divided by the narrow street. The two houses were connected by a bridge spanning the street. Not any old bridge: it was an exact replica of one of the bridges in Venice, a sentimental monument to an “international love affair.”

In the mornings, when the boys and I were busy in the classroom upstairs, Richard liked to retreat to the lower house to work undisturbed for a couple of hours, accompanied by a portable typewriter. The thoughts that went into this typewriter usually came out of it in the form of tightly crumpled balls of paper. Once, indiscreetly, I smoothed out a piece of this mental litter and discovered with a shock that it was blank.

At noon the typewriter accompanied Richard back across the Venetian bridge into the main room of the upper house. There it sat on a stool in front of a chair, paperless and silent. But apparently Richard liked to have it around him. It went wherever he did, jealously guarded by his Pekingese bitch, E’en So. Among all his wealth, his yachts, houses, cars, and wardrobes of clothes, it was perhaps the only object for which he felt any enduring affection.

That main room in the upper house was the centerpiece of the Casa Kimberley set. Here the family ate, drank, relaxed, entertained, traded the talk of the day, recited Shakespeare or declaimed Dunbar. A profusion of broad-leaved plants, an almost sensuous vegetation whose green set off the brilliant colors of a prodigal scattering of silk cushions, a balcony always open to light and air and a superb view of the mountains, soaring up out of the ocean, gave a sense of space and brightness which never failed to fill my heart with exuberance.

A couple of steps led up from the main room to an open courtyard, which swallowed the sun. It was flanked on one side by Raymond’s suite, on the other by the rooms occupied by the boys and me. The furnishings were tasteful but spare, almost frugal. However extravagant they might appear in public, my employers gave evidence in their private lives of tastes that were discreet to the point of understatement.

Leading off the main room and our courtyard was another flight of stairs, which led up to Richard and Elizabeth’s room. It was a small, modest room, the only one that was air-conditioned, but not otherwise noticeably different from any of the other rooms. It gave out onto a tiny terrace, where the master and mistress of Casa Kimberley could sunbathe undisturbed and explore, at last, having climbed so many, many stairs, such shreds of intimacy as were left them after the mauling of a cruelly inquisitive world.

On February 27, 1970, only a few days after my arrival, Elizabeth Taylor celebrated her thirty-eighth birthday. Her husband was forty-four. Both man and wife were in their prime. At the point when I briefly came into their lives they had been married for six years, having first met on the set of Cleopatra in 1961. The marriage was to last ten years. After the divorce in 1974 they remarried the following year—a last flicker of the Burton-Taylor fire before it finally went out.

At thirty-eight Elizabeth could perhaps no longer claim to be the most beautiful woman in the world as effortlessly as she had once done, but a quarter of a century after she had ridden to international stardom in a film called National Velvet she was still sensational to look at. She was a mature beauty; I admired her grace, her flair, the violet-colored eyes in her dark complexion, her sensual femininity. There was something gypsylike about her.

The personality was attractive—forthcoming, frank, and completely natural. In a woman as celebrated for her beauty as she was, it surprised me to find hardly a trace of vanity. She would change her clothes several times a day; she liked to present her attractions—but that was not vanity. She just enjoyed it. It was fun.

She wore her fame lightly, like a second skin. She never gave me the impression of having to live up to something, as I felt in Richard’s case.

Elizabeth’s fame was one of the things Richard had to live up to. He did so by giving her presents which acquired their own notoriety. The Burton-Taylor diamonds made newspaper headlines, and I know that one of the diamonds was the subject of a wager—Richard gave it to Elizabeth after losing a point to her during a game of table tennis.

The wore her fame lightly, like a second skin. She never gave me the impression of having to live up to something, as I felt in Richard’s case.

The world’s most precious lady deserved the most precious stones. In Richard’s eyes, the eyes of a boy of humble Welsh origins, those diamonds reflected something more: that he had become a partner worthy of Elizabeth Taylor.

As in many marriages, the love between them had been grafted to a family affair, to a common interest in their children. Richard cared for the children Elizabeth had brought into the marriage as if they had been his own. He was very much a family man. He spoke often and affectionately of Kate, his daughter by his first wife.

Elizabeth’s oldest child, Michael Wilding, was away in India at the time, but all the other children came to stay with their parents in Casa Kimberley. Christopher Wilding and his cousin remained there for as long as Richard and Elizabeth were in Mexico. Liza Todd, Elizabeth’s third child, came over from school in Europe during the Easter holidays. So did the fourth child, the Burtons’ adopted daughter, Maria.

Maria was their love child in all but the conventional sense of the word. The bond which the diamonds symbolized in public relied in private on the love they shared for thendaughter. With the help of a skilled surgeon, the child who had been physically handicapped since infancy had grown into a sturdy, attractive little girl. Perhaps Richard and Elizabeth no longer had very much to say to each other as man and wife, but what they had lost as lovers was more than compensated for by what they had gained as parents.

Elizabeth has a very limited vocabulary. That’s one of the differences between us. I have an immense vocabulary.”

Because of Elizabeth’s own playful nature, it was she who became the children’s obvious companion during the holidays. It was she who romped with them in the pool, arranged for the deep freeze to be stocked with hamburgers, and handed out photograph negatives through which they could view the eclipse of the sun. Her vitality, her immediacy, inspired the children with a sense of fun. Richard did not have that immediacy; he had staying power. His qualities emerged over distance and time. Thus it was Richard who wrote the letters to the boys after they had left Mexico, Elizabeth who added the postscripts.

I liked all the children. They were completely unspoiled. I got to know the two Christophers best. The nephew was more like Elizabeth in his character than the son; impulsive, outgoing, his temperament as suntanned as his skin. His talk was all of coral, surf, and lagoons. He reminded me of a splendid, untamed animal.

Christopher Wilding was a more withdrawn, pensive boy. Even his paler skin seemed to have retreated from direct contact with the sun. Perhaps he had already undergone enough exposure in his life.

The children supplied the linchpin of Richard and Elizabeth’s marriage. In that respect it was a conventional marriage. It was not hard to predict that when the children left home the marriage would break up. In that respect their marriage was also nothing unusual. They were, after all, only human.

Not long after Elizabeth’s birthday a fishing expedition was arranged for the whole family, the first of only five or six occasions during my three-month stay when Richard and Elizabeth ventured out of the house at all.

On the way out from Vallarta we cruised along the shore of the peninsula where The Night of the Iguana had been filmed. The original set, a village specially built for the film, still appeared to be intact, although it had remained uninhabited since.

Richard perked up when he saw the village, and related a few anecdotes. This led on to a discussion of fame. Didn’t he, I asked tentatively, find that constant exposure to the public eye was rather a two-edged honor?

“Well,” he replied, “I recently discovered what it’s like not to be the object of public attention. On location in Eastern Europe, I found myself having to wait in a queue— something I’ve not done for as long as I can remember. People didn’t recognize me. They hadn’t seen my films.”

“Wasn’t that rather nice for a change, not being recognized as a celebrity?”

“No. I hated it.”

At dinner that evening Richard got very drunk. Talking of Wales, and perhaps with more respect for Dylan Thomas in his head than respect for agricultural fact, he tossed out the phrase “fecund fields."

Elizabeth gave a snort. “Fecund! Ha!”

Richard turned to me and said coldly, “Elizabeth has a very limited vocabulary, David. That’s one of the differences between us. I have an immense vocabulary.”

Elizabeth wouldn’t let go. “Fecund, for Christ’s sake!”

She stalked out of the room. Alone at the table, Richard and I indulged in a little patter on the subject of literature. It wasn’t hard to guess that Dylan Thomas was one of Richard’s heroes. In Los Angeles I had picked up a slim volume that Richard had published; a story about a Christmas in Wales, I seem to remember. It was not without merit, but it was pastiche, written on Richard’s portable typewriter, with Dylan guiding his fingers to the keys.

I told Richard frankly my opinion of his book.

“Oh, but that’s dreadful, David. You shouldn’t have bothered to read it.”

And he steered the conversation back to poetry and another of his anecdotes about Dylan. I thought Dylan was splendid, I said, but I had more respect for T. S. Eliot.

“Eliot? I once met him at a party. Dylan was there too. Eliot said nothing. Dylan upstaged him all the time. There was no way he could compete with Dylan in the same room.”

Richard used the word upstaging on another occasion, some months later, after he had been to see Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud in David Storey’s play Home. “It was marvelous,” he said affectionately, “to watch those two old codgers upstaging one another."

That was his only comment on the play.

Upstaging was a key word in Richard Burton’s “immense” vocabulary. A powerful man and a powerful actor, he had always been very good at it himself. Critics had noted this aspect of his talent, not with approval, even in the early 1950s. It had been known to jeopardize a production.

And up there in the room at the top, on that pinnacle of success, it was the same issue that jeopardized his marriage. All efforts to upstage Elizabeth Taylor were doomed to failure. Richard might send out as many invitations as he liked with Mr. and Mrs. Richard Burton printed at the head of the page, but it was Mr. and Mrs. Taylor whom the majority of their guests wanted to come and see.

When, for instance, an emissary arrived with an invitation from a minister in the Mexican government, which he presented with florid Latin courtesy, there can have been no doubt as to whom the caballero had in mind. A Mexican Air Force plane, suitably camouflaged for such a delicate mission, was already waiting on the tarmac of the Vallarta airport to conduct the distinguished guests, whenever, at their gracious convenience...

I asked Richard’s private secretary, Jim Benton, what all this was about.

“Oh, there’s a development project in hand,” he said vaguely.

A week later a very tired-looking pilot brought a very hot plane down onto a sandy airstrip in the jungle. The minister who had issued the original invitation was mysteriously indisposed, but his son Carlos, a massive young man with a hooknose, was waiting to greet the distinguished guests. The party was paddled across a lagoon in a convoy of six canoes.

“Would you like to have this lagoon?” inquired Carlos through an interpreter.

“How sweet of you,” said Elizabeth.

On the far side of the lagoon we climbed a knoll overlooking the beach and the thunderous surf.

“I thought you might like to build a house here,” said Carlos. “The land will be a gift, of course. Really, as much as you like...”

He gestured vaguely toward the horizon.

At the bottom of the knoll a truck was waiting beside a posse of horses. We were given a choice of motorized or four-legged transport on the final stage of the journey to the ranch where Carlos had invited us to lunch.

The Burtons, to their credit, were not going to let themselves be dangled as bait for the fat cats Carlos was hoping would invest in his scheme for a millionaires’ paradise along his private stretch of coast. The Burtons did not say so in as many words, but that was the message. Carlos, who was not by nature a very forthcoming man, disappeared altogether behind a mask of silence at the lunch at his ranch, increasing his already marked resemblance to a stone effigy.

Over the marinated-fish hors d’oeuvre, Elizabeth burbled on enthusiastically about a splendid white horse she had spotted from the air. The interpreter burbled in hot pursuit.

When the company rose from the table at the end of lunch, the white horse admired by Elizabeth had been identified by an air patrol sent out on Carlos’s instructions, separated from the herd by cowboys informed by radio of its whereabouts, lassoed, and ridden back to the ranch.

There was only one problem: the animal might look very fine from the air, but on closer inspection it turned out that its ribs were showing. Carlos could not present so noble a horsewoman with so wretched a mount. He would accordingly feel highly honored if she would accept his own white stallion instead.

Elizabeth accepted. She would have been very foolish not to. The hospitality of Carlos was extended not as an invitation but as a command. Thus no objections were raised when Carlos suggested we fly on to his “apartment” in Guadalajara, and none of us was at all surprised when the apartment revealed itself as a palace set in spacious grounds. It became difficult to express recognition of our host’s generosity when a careless word of praise for anything we saw meant to be encumbered with it instantly as an incontestable gift. Elizabeth acquired a second horse, with a magnificent silver-inlaid saddle for the first, and Richard only narrowly averted being presented with a peacock.

It could be said of Elizabeth Taylor in her heyday, as it was once allegedly said of Napoleon, that she extended the boundaries of Fame. It was a hard act to follow, and nobody can have been more aware of that than Richard Burton.

Throughout March the heavy drinking continued; while the sun shone brilliantly outside, monsoon weather in Casa Kimberley. On one evening Richard was in such a bad state that Elizabeth asked me to keep the boys occupied outside the house for a couple of hours.

She began to take me into her confidence. There were few places in that airy, open house where confidences could be safely exchanged, and thus it came about that she and I were sometimes closeted in the storeroom of the lower house. We were once discovered there by Richard, who unexpectedly came down to fetch his beloved typewriter and overheard our voices.

“Who’s that in there?’’ he boomed, like Hamlet challenging his father’s ghost.

“It’s me," replied the tutor’s ghost. “I’m in here with Elizabeth.”

“Elizabeth? What? My Elizabeth?”

He never brought the subject up afterward.

Once, on the beach, while Christopher wandered in search of shells, his mother talked to me about her marriage. She loved her husband. But did he love her? She worried that she was losing him. She had doubts about herself. When she called herself “an old bag,” she was not fishing for compliments. I was convinced of her sincerity.

“The trouble is,” she said sadly, “I think I just bore him."

I would have put the problem differently: the trouble was that Richard bored himself.

Richard never disclosed his feelings in the way that Elizabeth did. He was not a disclosing kind of man. Instead he sent out signals, a code which I had to learn to read. I began to realize that now that he had become accustomed to my presence about the house, he might, in fact, enjoy my companionship.

Playing pool was one form of companionship, Scrabble another. Scrabble symbolized the code: the knowledge and appreciation of words and all literary matters. Richard did not tell people he was in distress; he recited Dunbar instead.

He had immoderate respect for academic learning. It is characteristic that the only anecdote which Richard told me about Marlon Brando was that he had taught himself Greek, a fact which I still find hard to believe, but I have it on Richard’s authority.

My first judgment of Richard was that he was an intellectual snob, arrogant, bombastic, and given to pedantry. But he was not a snob or a pedant. He only posed as one. He put it up in front of himself as a security screen, proving to the world that he still had serious standards and values, which in private he feared he was losing, or might even have lost altogether.

Having embarked on his career as a star, for want of a better life, Richard reoriented his ambition according to the standards by which movie stars are judged: the standards of Hollywood. And Hollywood’s highest accolade was, of course, an Oscar.

So far the Oscar had eluded his grasp. He had been nominated several times, without success.

The savage bout of drinking throughout that March culminated in his recital of Dunbar’s refrain: The fear of death anguishes me! The next morning he went on the wagon, and a week later, still aboard, he was rolling north to L. A. for the presentation of the Academy Awards. He had been nominated for his performance in Anne of the Thousand Days. The other contestants in 1970 were Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman, Peter O’Toole, and John Wayne. John Wayne won, but Richard accepted the decision with good grace. Good old John Wayne, ten feet tall, great Hollywood character, loyal servant of the film industry, receives his just reward. Richard’s slightly condescending interpretation of the criteria for the Academy’s decision allowed his self-confidence to escape unbruised. And anyhow, what did it matter? He had accomplished something possibly more important than the Oscar. He was still on the wagon.

Continued on page 128

Continued from page 80

I am very glad, before our ways parted, to have seen what Richard could be like when he was off the booze. He was a transformed man; perhaps it was the best transformation of his career. The ease and naturalness with which he played a sober part convinced me of Richard’s merits as a man. The moody Heathcliff, the swaggering Antony, were troubled phantoms, released from the bottle like evil djins. His face cleared, his eyes brightened, he talked better, began to take an interest in things, and for the first time I saw that he was indeed, still, a very fine-looking man.

We all went out dancing—Richard, Elizabeth, the whole family. Only a month before, it would have seemed inconceivable. I don’t think the two of them had been out dancing in years for their own benefit rather than for the onlookers. Dancing days, happy days, practical jokes and pranks in the main room of the upper house. Although still abstinent himself, Richard used to mix me devastating martinis, which is rather like a pyromaniac constructing firebombs for someone else to throw.

They were quite something, those martinis. On one occasion they transformed me into a matador and Elizabeth into a bull. She was a very fiery bull, and a courageous one too, for I was equipped with real banderillas, souvenirs of a corrida I had seen in Guadalajara. Richard played the arena and 10,000 spectators, without exaggeration a monumental part.

A final cameo from a strange, eventful history which already seemed unreal. Cameras off. The tigerish month of May, the season of fierce heat, had arrived in Mexico, bringing silence to Casa Kimberley. The two Christophers and I left for Europe, where my year as their tutor would be completed, Richard and Elizabeth for other locations, other films, in which I would no longer play a part.

Ours wasn’t finished yet, however. I had seen the rushes of Richard Burton on the Casa Kimberley set. They were fine as far as they went. But there was still a lot of editing to do.

The Dunbar verses which Richard Burton so memorably recited came from a poem called “Lament for the Makaris.” It is an elegy, mourning the transitoriness of worldly things. Why, in all the wealth of English literature, should such an obscure poem as this “Lament for the Makaris” have remained so obstinately in the forty-fouryear-old Richard Burton’s memory? I suggest that he was reciting his own lament, not for the things which had departed from his world (for they were still there), but for things on which, in retrospect mistakenly, he had himself turned his back.

It was not the fear of death which anguished Richard Burton. It was the fear that he had betrayed his own talent.

Or had it betrayed him?

Laurence Olivier was the standard by which critics had once measured the young Richard Burton. Richard also saw himself as taking the Greatest Actor’s mantle, but with a self-knowledge that was denied his admirers he described his fitness to be Olivier's successor in very much more modest terms: “I’m really the poor man’s Olivier."

The name became a burden and an obsession. “If you're going to make rubbish, be the best rubbish in it. I keep telling Larry Olivier that."

Which Olivier was he telling? Larry? Or the poor man’s Olivier?

The poor man’s Olivier was offered and accepted the part of Antony in Cleopatra. Larry Olivier was offered the part of Caesar, and declined.

Larry Olivier did not take his poor relation’s advice. He is alleged to have offered him his own instead. “You must decide what you want to be—a household word or a good actor."

Richard made his choice. There was not much Olivier left in the poor man’s Olivier at the end.

I saw him perform on the stage only once. Nevill Coghill coaxed him back to the Oxford Playhouse in 1966 for what by then had become a very rare theater appearance. He agreed to play the title part in Marlowe’s play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.

Marlowe’s Faustus (like Goethe’s later Faust) is based on a medieval legend about a man who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for universal knowledge, worldly riches, and power. The devil gratifies all his desires, and at Faustus’s bidding even summons up the apparition of Helen of Troy (played by Elizabeth Taylor in the Oxford production). Satiated by all these marvels, but still strangely unsatisfied, Faustus faces the hour when the devil will fetch him to damnation. He repents, but his repentance comes too late.

Richard Burton offered journalists his comments on the role: “I’ve been waiting to play Faustus for more than twenty years. I know the part, but not as well as I thought. A lot of Marlowe’s lines started coming out as Burton lines.”

Dr. Faustus was renowned for his learning in the art of black magic; an ambiguous gift, for it was the art of black magic that gave him access to the devil.

Richard Burton practiced his own kind of magic with a naturally compelling presence, a naturally marvelous voice. But was this magic a reliable substitute for the solid foundation of technique?

As early as 1949 the distinguished film critic C. A. Lejeune, one of Kenneth Tynan’s predecessors in the columns of the Observer, remarked how the young Richard Burton had “a trick of getting the maximum effect with the minimum of fuss.”

In 1981 I worked on a studio recording with Anthony Quayle in London. Quayle knew Richard intimately from their years together in Stratford during the early 1950s. He told me how he had once invited Richard to join him for a repertory season; the experience, he suggested, would help to improve his technique.

Richard declined the invitation. “I’m afraid,” he explained to Quayle, “that technique would interfere with what is my real asset—a knack. I just have a knack, you see.”

He did indeed. He had the knack of the devil.

Richard played on two tables and lost on both: no Oscar for the obvious, easy choice and no knighthood for the difficult, more rewarding one.

Gradually we lost touch. There was a brief meeting at the Dorchester, followed by a visit to watch him on location when he was filming Villain in London. A year later, a lunch together at a studio in Munich. He wrote a few letters. He was a very loyal friend. I gave up my theater ambitions and went to Japan, in search of another enigma. It was not time or distance that separated us. We were separated by his fame. He again became someone whom I heard of only in newspaper headlines.

The Herald Tribune. Death of Richard Burton, actor, aged fifty-eight.

The private film which we had made together in Mexico could now be given a title: The Tragical History of Richard Burton.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now