Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

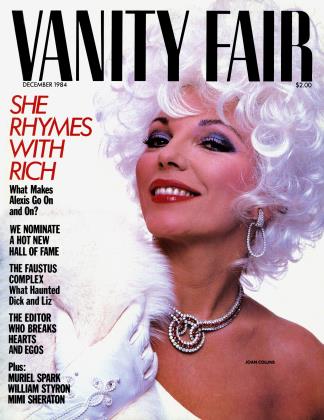

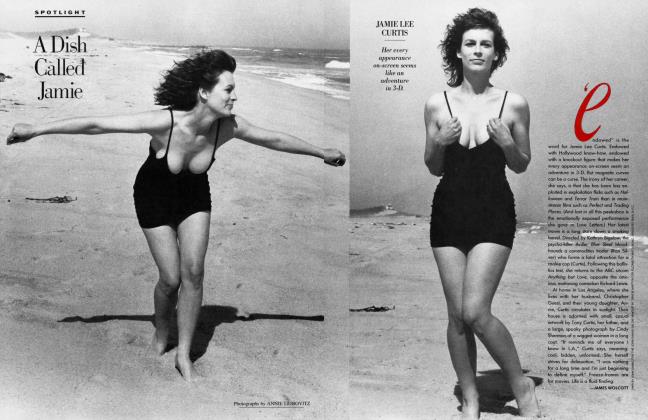

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDynasty isn’t just everybody’s favorite trash wallow; it’s the strangest phenomenon on TV. STEPHEN SCHIFF examines the first mannerist soap

December 1984 Stephen SchiffDynasty isn’t just everybody’s favorite trash wallow; it’s the strangest phenomenon on TV. STEPHEN SCHIFF examines the first mannerist soap

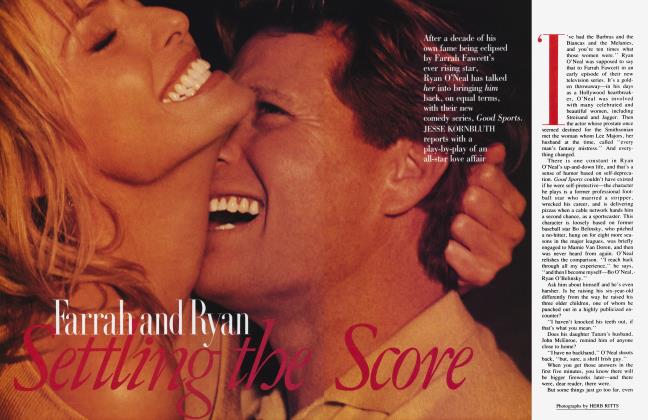

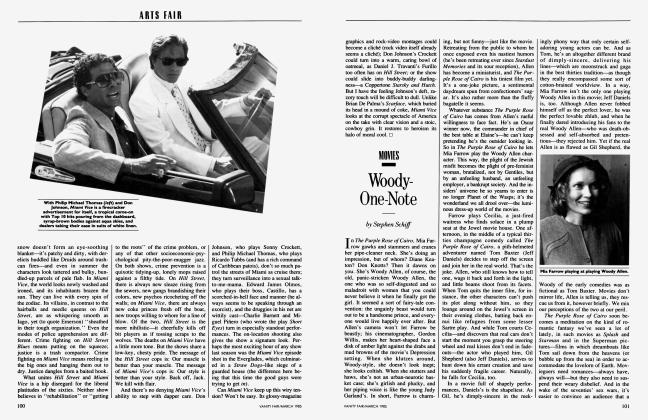

December 1984 Stephen SchiffIn an antique-clothing store in New York’s East Village, the clerks are dressed in early Road Warrior—leathers, Mohawks, spike bracelets, chains. They look as though they had eaten rats and small children for breakfast, but what they are discussing, in the inflections and argot of the Village gay community, is Dynasty. “Can you believe what Alexis did last night?" they murmur in hushed, wondering voices. “I mean, that’s just not like her.” Alexis is, of course, the bitch-queen portrayed by Joan Collins, who not so long ago was a washed-up movie actress reduced to playing aging-floozy roles in Farrah Fawcett pictures. Now she is probably the most popular actress in America, a worldly, commanding figure, a star to her fingertips, admired by shopgirls and imitated by drag queens—the Joan Crawford of our age. Dynasty, meanwhile, is watched by 100 million people in seventy-eight countries. And the East Village admirers I overheard don’t talk about it as if it were their favorite program. They talk about it as if it were their life.

For some people, it is. Dynasty’s creator, Esther Shapiro, knows of a coven of BBD&O executives who re-enact Dynasty scripts every week, over champagne and caviar. There are Dynasty-inspired restaurants, with goodies like Alexis burgers and Krystle fries. There are Dynasty fancy-dress balls (one in Oslo was attended by most of the Norwegian government). There are even Dynasty discussion groups, whose members meet, like so many repentant drug abusers, the day after the show—to, you know, talk things out. It isn’t the program’s prodigious ratings alone that are intriguing, it’s the nature of those ratings. Dynasty’s popularity is quirky, broad yet extremely private, lowest-common-denominator yet highbrow-hip. The show is oxymoronic: it’s a mass-market cult. Dynasty couldn’t have happened in the I-believe-in-me seventies, because it’s not about any of the me’s watching it. It’s about people wholly unlike us, people whose putative glamour we enjoy envying—an oil baron, Blake Carrington (John Forsythe), his suffocatingly virtuous second wife, Krystle (Linda Evans), and his scheming, dastardly first wife, Alexis. Dynasty is a fun-house mirror for the eighties; it reflects the era’s aspirations, tastes, and regrets.

What’s most revealing, however, is its appeal to gays. Dynasty night is an inviolable ritual in gay bars across the country; at one in Los Angeles, tapes of epic catfights between Alexis and Krystle are played over and over on an endless loop. A ritual known as D.&D.—Dinner and Dynasty—has become a fixture of gay social life. But what fascinates me most is that the very factors which give the show its gay-cult appeal are also the ones that make it so popular with everyone else. Dynasty represents something extraordinary: the incursion of so-called gay taste into the mainstream of American culture.

When you talk to television people about a trashy show’s appeal, they invariably try to convince you of its value to society. They want you to think that watching, say, The Love Boat will liberate women, cure diabetes, and revitalize the United Nations. Most of the Dynasty people are no different. According to them, Dynasty makes drab lives brighter, has restored dignity to women over thirty-five (they’ve got a point there), cheers the poor by saddling rich people with these horrible problems. They tell you Dynasty is good drama; they talk about its “classical” structure. And the marvelous thing about all this foofaraw is that they believe it. If you mention the show’s homosexual following, they immediately launch into what I’ve come to regard as the Steven Spiel. This is about how gays adore the show because Blake’s son, Steven, is a manly, dignified homosexual who had a manly, dignified homosexual relationship and who, though currently married to the entirely female Claudia (Pamela Bellwood), Has Not Stopped Being Homosexual (watch for thorns aplenty in the conjugal bed, they hint). Which is perfectly laudable, except that I suspect Dynasty would have garnered its gay following had there never been a Steven Carrington. What gays (and most everyone else) watch it for is its campiness, in the clothes, the decor, the dialogue, and the situations—and, most of all, in the character of Alexis. Dynasty embodies the return of a phenomenon I had thought long dead: camp in its original form—earnest, naïve, genuinely impassioned, and genuinely ridiculous.

Defining camp is dangerous—not to mention in appalling taste—because camp defined no longer is. Definition makes things accessible, whereas camp is willfully elusive; it is by nature elitist, knowing, and hipper-than-thou. What’s more, camp isn’t inherent in a work. It lies somewhere between the work and its appreciator, or, rather, in the way the space between work and appreciator fluctuates. The camp sensation is a little like Brecht’s alienation effect, because distance is essential to it; you must be able both to adore and to jeer, to be sucked in and then to pull back in derision. The quality of that derision is peculiar to camp: it is, paradoxically, appreciative. "Dynasty is great to dish,” a friend sums up, and the idea of something being loved because it generously invites jeering is at the heart of camp. “You can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously,” wrote Christopher Isherwood in his novel The World in the Evening. “You’re not making fun of it; you’re making fun out of it.”

In this sense, camp, which had long been a pleasure restricted almost exclusively to gays, leapt out of the closet in the sixties—it was the surprise in the Cracker Jack box of pop art. Susan Sontag discovered it; suddenly everybody wanted a piece of it. I date its demise (or, as it turns out, its enforced hibernation) to the introduction of the Batman TV show in 1966, two years after Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp.’ ” With its goofy comic-strip balloons (Biff! Bam! Kapow!) and its pointedly banal acting, Batman was manufactured camp, a kind of cultural polyester. And from this synthetic goo grew the spoof, which has plagued us ever since—from Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, with their self-conscious lampooning of forties serials, to the endless round of seventies detective spoofs and Western spoofs and spy spoofs. Amid the hubbub, true camp all but disappeared, except in ballet and opera, which remained frozen in the endearingly silly forms they’d occupied for centuries, and in such debased nonsense as game shows and the Miss America Pageant.

Dynasty’s admirers don’t talk about it as if it were their favorite program, They talk about it as if it were their life.

Still, all the spoofing and lampooning has created a certain air of detachment: we now look at everything with chill, appraising eyes. And this distancing has paved the way for Dynasty, the first authentic camp that the entire culture appreciates as such. All kinds of people watch this show, and virtually all of them find in it the experience once savored by only a few: you weep with it and hoot at it at the same time.

Some of the same could be said for other nighttime soaps, of course, but none of them reflects that elusive union of gay and mainstream tastes. Knots Landing, for instance, is terribly suburban and sincere; it has a concerned, Movie of the Week quality. And I find Falcon Crest completely unengaging. Its single potentially intriguing figure, Jane Wyman’s Angela Channing, turns out to be a glowering stiff; she’s what a golem looks like after it’s won the lottery. Paper Dolls is amusing but strains to be trashy; already it’s making Danielle Steel look like Daniel Defoe. And Dallas is too earthy and crass to be camp. It’s about business wars, not style wars, and it never gets drunk on artifice the way Dynasty does; it never seems so self-delusive, so madly “off.” Larry Hagman plays J.R. with a likable smirk, but he’s a TV actor, winking at his audience just as Johnny Carson winks at his. He could never be absurdly, cinematically grand in the swanning Joan-Collins manner. On Dallas, men are interesting but never pretty, and women are pretty but never interesting. It’s a resolutely macho show.

Dynasty, on the other hand, is an epicene triumph. Here the men are comelier than the women—in fact, such lackluster actors as Michael Nader and Gordon Thomson have a kind of sailor-boy butchness. Linda Evans, with her white hair, orange skin, and milk-blue eyes, is striking in the manner of a marooned alien, the Matron Who Fell to Earth; she’s friendly, but terminally out of it. And the younger women, the ones who on other shows would be centerfold fodder, are a motley lot, more presentable than alluring, and sometimes almost grotesque. Take the recently departed Kathleen Beller. Whenever she showed up in one of the swanky costumes Dynasty is famous for, you wanted to sidle up to her and whisper, “Nice outfit. Did it come with a banjo?”

Even Alexis seems flinty, unmarriageable, mannish; there’s a bizarre transvestite aura about her. Her broad-shouldered, over-tailored suits fit her oddly, and her bosom seems exaggerated, the way a female impersonator’s does. Her hair is wiglike. One often catches her stomping around on her short legs like Jimmy Hoffa in high dudgeon. And perhaps owing to John Forsythe’s Washington-crossing-the-Delaware acting style, you never sense that Blake Carrington feels anything sexual toward her. As Alexis pines and plots, she reminds one of an aging homosexual in love with a beautiful straight man who will never think of him in “that way.”

Fortunately, Alexis is a perfect bitch, and perfect bitches are prized creatures—they are the apotheosis of the camp aesthetic. Camp reserves its greatest admiration for self-invention, for the construction of an original, seamless, dazzlingly decorative character, like Beau Brummell or Quentin Crisp. As Oscar Wilde famously put it, “One should either be a work of art or wear a work of art.” The self-invention of Joan Crawford or Bette Davis or Tallulah Bankhead or Mae West is a heroic paradigm of what the gay man may dream of being in a society whose “normal” roles he doesn’t fill. He creates an alternative role, richer and more faceted than the ones others hanker after, and impervious to their standards, politics, and morals. Mere bitchiness isn’t enough. Bitches have long been the empresses of soap opera, but the young harridans on daytime soaps have no camp cachet. Who can get up any dander over a tawdry bit of fluff like Tracey Bregman or Tasia Valenza when magnificent dragons like Jeane Kirkpatrick (surely the Joan Crawford of public life) lurk among us? A woman you love to hate has to radiate experience, finesse—it’s important that Joan Collins is over fifty. Like the aging Crawford looming in her swivel chair at Pepsi-Cola board meetings, Collins’s Alexis is oddly reassuring to women and to gay men. Your looks needn’t flee with your youth, she promises. And there is power—practical, world-beating, money-making power—in femininity. And— the bitch’s credo—a well-turned insult can defeat an arsenal.

Dynasty is camp in its original form—earnest, naive, genuinely impassioned, and genuinely ridiculous.

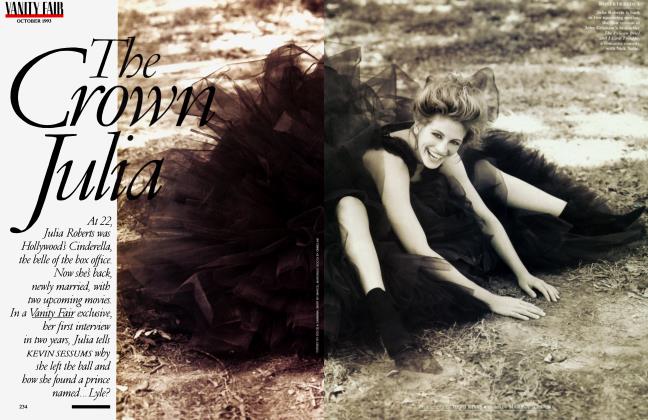

It’s vital, too, that we think of Joan Collins as being Alexis-like off-camera. On the Dynasty set, she strides back to her dressing room with a menacing click of heels; her eyes flash, her shoulders push, her speech is haughty, purring, imperious. Suddenly she turns and blurts, “Look at this. Do you think this is a star’s dressing room? This is not. I went to see some people in Las Vegas who have a dressing room that is a hundred times this size, covered in fur and mirrors.” As she speaks, one recognizes in her the sort of exquisite the world has not seen since the Hollywood-studio era of the thirties and forties. Then there were Stars, people like Crawford who when they weren’t on the screen were playing the role in real life, dressing a certain way, talking a certain way, even loving and marrying and raising children a certain way. Joan Collins has invented herself in the image of a movie star.

Camp self-invention has nothing to do with inner character and everything to do with clothes, hair, gestures. It concocts a methodology for things that never required methods before—hence the camp appeal of Diana Vreeland’s recent memoir, with its arcane advice on the care and feeding of shoe bottoms. The mundane is transfigured; to Beau Brummell, the sublime tying of a cravat was as admirable as the sublime composition of an opera. In this regard, the ultimate camp formulation is Joan Crawford’s “No wire hangers!” For her, arranging the armoire was the subtlest of sciences.

Likewise, Alexis is potent partly because she has perfected areas the rest of us pay scant attention to. As Nolan Miller, the show’s wardrobe designer, explains, “My role model for Alexis is Crawford. I designed for her for the last twenty years of her life. Crawford, Jane Wyman, Ginger Rogers, Lana Turner—I mean, don’t ask one of these ladies about a pair of shoes that goes with three different outfits. Unh-unh. That outfit has its shoes, it has its gloves, it has its jewelry, its hat. Just try telling one of them to mix and match. And it’s very intimidating, that studied kind of look. It’s like ‘Everybody, stand back.'"

Television drama hadn’t bothered much with clothes before. Or with food. One of the show’s writer-producers, Ed DeBlasio, describes an early Collins shooting: “She was in a kitchen with Krystle, and she punctuated her line by picking up a scallion and biting off the white end of it. It was stunning. So now we try to have her eating in every show." She eats better than anyone. Lashing out at Joseph (Lee Bergere), the Carringtons’ erstwhile majordomo, she pops a grape into her mouth and lets it loll about as she talks. It’s an amazing piece of work, because the grape becomes a metaphor for the insults she’s spewing; you can see her savoring them, rolling them around against her palate, and then digging in for the final, juicy bite.

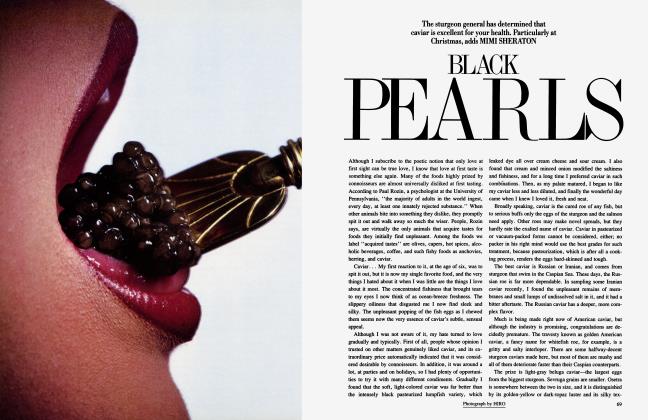

This attention to style has made Dynasty the first mannerist soap opera, the beginning of a nighttime-serial baroque. Soap opera itself is an exhausted form; in fact, the very idea of plot twists has become a bore. When this sort of thing happens in art—when, for instance, the notion of painting yet another beatific Madonna grows stultifying—artists resort to expressive stylization; the “content” becomes less meaningful than the manner in which it’s expressed. The elongated necks and hands that such Mannerist painters as Parmigianino and El Greco used to emphasize piety became more fascinating than the piety itself. And so with Dynasty, where the embellishments—costumes, cars, champagne— not only buttress the thing they embellish but dominate it. Look at the Christmas merchandising of Dynasty, an act that severs the show’s entertaining style from its pedestrian subject matter. Toned-down versions of Nolan Miller’s rather alarming clothes, a $150-an-ounce perfume, and other scraps of the Carrington beau monde are now being marketed to a bourgeois clientele. That unattainable life-style has become attainable— you buy the fur and learn the insults, crunch the caviar and then storm out of the room. (What kind of woman, I wonder, is going to want these fashions? Even the consumers who believed they could buy a little class by having the words Calvin Klein stitched to their fannies may balk at shelling out $1,000 for a garment which signifies that its wearer watches TV.)

Though Dynasty’s version of la vie en rose is vulgar and garish, it at least codifies a certain kind of taste.

Extreme stylization has always appealed to camp-lovers. But why do millions delight in it on Dynasty? The reason, I think, has to do with eighties politics. The soap opera is a populist form, but Dynasty’s chichi creates an antipopulist setting. And America has never been less populist than it has been under Ronald Reagan. No one wants to be a grimy prole in a society that offers no rewards to grimy proles—not even the assumption of virtue. Under the tenets of supply-side economics, eighties America not only kowtows to the rich but holds them up as a moral standard. It is they who, given money enough and tax breaks, will kindly allow their prosperity to trickle down to the rest of us, thereby saving the American economy and Life as We Know It.

It follows that if you’re not rich and virtuous you can seem virtuous by emulating the rich. And if the rich live in high style, then the nuances of high style must be learned. But we Americans have only the dimmest notion of how wealthy people are supposed to behave—our aristocrats, after all, are the descendants of ruffians and robber barons. We require instruction. And though Dynasty’s version of la vie en rose is vulgar and garish, it at least codifies taste for those who need it codified. The glasses on the show are always Baccarat crystal, the champagne always vintage; even the food that Linda Evans tosses to her carp is the right kind of carp food, the kind everybody’s using in Gstaad and Marbella this year.

In fact, Dynasty’s snobby fetishism has a quasi-religious quality to it; the show’s makers are secular sages, dispensing Hollywood wisdom on breeding and protocol. There’s something almost uplifting about it. Dynasty fans may chortle when they see Alexis lounging around her apartment in finery appropriate to a state dinner, but they’re also learning how one might dress for a state dinner. The chortling saves them from feeling craven and materialistic, just as it saves them from feeling stupid when they get all teary during the mushy parts. Dynasty’s viewers push camp to a new level— they’re not just hooting and weeping at the same time, they’re hooting and taking notes. Thus does Joe Six-pack become an eighties-style aesthete, the unwitting heir to people he might well despise, had he ever heard of them. Beau Brummell and Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley and Max Beerbohm, Cecil Beaton and Ronald Firbank—they all must be squealing in their graves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now