Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBRAINSTORMING WITH BOROFSKY

Wet Paint

Christopher Knight

ARTS FAIR

SEPTEMBER

A new season with artistic license. Metropolitan minceur. Musical madness. Bayou Giselles. Pulitzers on Pulitzers. Bookends. Art is all. All is fair.

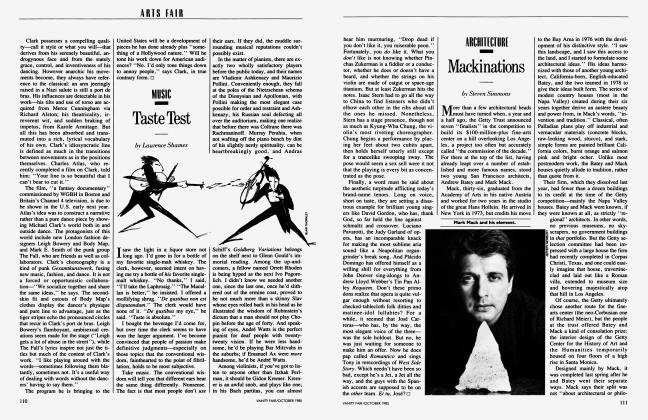

In 1975, Jonathan Borofsky blew his brains out all over Paula Cooper’s gallery in SoHo. For his inaugural exhibition, the artist gathered together the disparate contents of his studio—finished and half-finished sculptures, written messages and ordinary objects, doodles and scribbled-on canvases—and deposited them in the gallery. The private, internalized realm of a little-known artist’s studio was transferred to the public space of a commercial gallery. It was as if those accumulated artifacts were the residue of almost everything that had been going on inside Borofsky and he had exploded them into a walk-in world.

In an increasingly refined manner, Borofsky has repeated that exhilarating release in a score of museums and galleries throughout America and Europe during the past nine years to the point where news of a Borofsky show is greeted with ardent anticipation. This fall the Philadelphia Museum of Art has organized a mid-career retrospective of his work in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York, to open in Philadelphia on October 7.

That first public installation in 1975 included a seminal work called Counting, begun in 1969 and still in progress today at Borofsky’s studio in Venice, California. For two, four, even six hours a day, he filled sheet after sheet of graph paper with sequential numbers, beginning with one and rushing headlong toward infinity. This decidedly rational work is also crazed, dazzlingly transcendent, and possibly a sly gimmick for some art edition of the Guinness Book of World Records.

Being inside a Borofsky installation is like being inside another person’s brain—or, more precisely, inside that mysterious but critical zone where the brain’s rational and highly ordered half interacts with its intuitive, emotionally messy partner. The interaction between contradictions rather than any forced synthesis is what generates the vivifying energy in Borofsky’s art. Take the “hammering man,” a work that has assumed many forms in the past eight years, including that of a twenty-fourfoot-tall wooden silhouette sporting a mechanized arm that relentlessly pounds a hammer. This figure originated in a picture that Borofsky had found in an old Book of Knowledge of a worker striking a wooden shoe. By the time he used the image for a graphic work in the winter of 1981, the desperate strikes in Poland had captured newspaper headlines, and “to strike” took on antithetical meanings in Borofsky’s single image: to work and not to work.

Borofsky helped vitalize the torpid American art world of the mid-seventies. At forty-one, he is at the center of the international art scene that has erupted over the past few years—a scene that Borofsky’s own art has played a key role in generating. The art of pure form offered by minimalism and the art of pure idea put forth by conceptualism together appeared to have led to a dead end. But some artists, Borofsky among them, chose to drive straight through the middle of the cul-de-sac. An abiding interest in the minimalist sculpture of Carl Andre and wall drawings of Sol LeWitt stood him in good stead. (So too did the nearly two years, 1968-70, he spent confining his own art to the accumulation of written notes to himself.) Roiling around in Borofsky’s brain, these spare, stripped-down modes eventually gave birth to a new consciousness. Amid murmurings of a pluralist splintering newly under way in the art world, Borofsky was quickly becoming a kind of one-man pluralist band.

His art has grown more confident and resonant. Along the way he’s developed an ever growing cast of characters who wield a closetful of props and, by turns, step to center stage, hang back in the wings, change scale, burst forth from who knows where, or turn into something else at the drop of a hammer. Among them is a “molecule man” in a state of advanced perforation; a running figure nimbly glancing back over his shoulder; a fingerprint face; a flying man suspended in air; a Ping-Pong table; and a rabbitlike head with ears on the alert and eyes a pair of dazed spirals. Often Borofsky will use a projector to throw one small image from a drawing across the room, bending it around corners and stretching it up and over the ceiling. Painted directly on the enveloping surfaces of the room, the image retains the sense of having been projected, but its unseen source can be traced only to the emptiness of the room itself, rather like a thought that has materialized outward.

His art is unmistakable, though it employs no single identifiable style. Rather, the work has style in the sense of its pronounced personality, a style of “inclusive generosity.” His art gathers contradictions together in an embrace and gives them back freely to the viewer. When you’re inside Borofsky’s brain, you begin to have the uncanny realization that it’s as much your brain as his; the feeling is of having been nudged into a waking dream state.

Dreams have furnished raw material for Borofsky for more than a decade. As a matter of course he jots them down and later redraws them in a notebook. Like his other work, the dream notes are “signed” with the current number in his ongoing march toward infinity: “I dreamed I was taller than Picasso— 2175191.” Or “I dreamed that Salvador Dali wrote me a letter. Dear Jon, There is very little difference between the commonplace and the avant-garde. Yours truely [sic], Salvador Dali— 2487690.”

Borofsky’s art offers no radiant vision of the future. For linear progress, perhaps the last great illusion of the modernist dream, is now in full collapse. He posits a whirlwind of crosspollination in its place. Crisis, as the art historian Jacob Burckhardt long ago divined, is itself an authentic sign of vitality. It is Borofsky’s achievement to have turned away from annihilation or escape and toward the fertilization of human thought. That’s what makes brainstorming with the molecule man so exhilarating an escapade.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now