Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Eye of Christophe Janet

The $2,800 lady he picked up at Christie's is a million-dollar Gainsborough

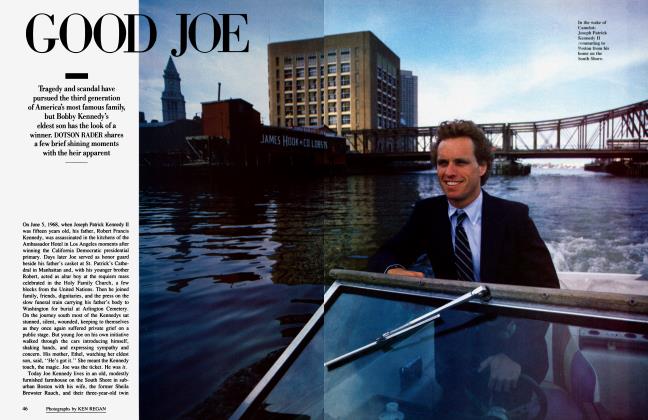

CHRISTOPHE Janet, a twenty-seven-year-old dealer in old-master paintings, has uncovered another long-lost masterpiece—and once again upset his enemies—on the way to making another million dollars.

He discovered the eight-foothigh portrait of Catherine Eden Moore, a court beauty from the reign of George III, in a dark comer at Christie’s East, in New York. The picture, which was a mess, was catalogued “manner of Gainsborough.” Janet knew better. He bid $2,800 for it, and he estimates that he will spend more than $10,000 to have it restored. And he will soon sell it, he says without hesitation, for more than a million dollars. He will unveil the portrait in his Manhattan gallery in October.

“It’s really unfair to call it a coup,” he says immodestly, in a thick French accent, between bites of Dover sole at Les Pleiades. “Anyone who knows Gainsborough would have noticed that it was real. It’s just that no one in this country knows. ’ ’

Perhaps. But those who saw the painting at Christie’s say it looked like one of thousands of fake portraits commissioned by ancestor-hungry nouveaux riches at the turn of the century. And among those experts there are a number of recent arrivals to the old-master field in New York. Paris’s Didier Aaron has sent his son Herve. The London galleries Colnaghi and Noortman & Brod have opened branches off upper Madison Avenue. Add to them the established dealers Clyde Newhouse and Richard Feigen, as well as Sotheby’s and Christie’s. It must be assumed that someone knew.

And like Ian Kennedy, of Christie’s, they would remark on Janet’s arrogance: “Janet again!” said Kennedy with distaste. “He likes to make a big deal about his discoveries. Trumpet them to the world. The truth is that you can’t be a successful old-master dealer without making discoveries. Most of the dealers keep it quiet. ’ ’

The arrogance of youth. The arrogance of success. The arrogance of the French. The arrogance of Christophe Janet. The eye of Christophe Janet. Nothing could have stopped this Parisian who left home at sixteen to study art history and economics at Yale, discovered his first lost masterpiece at twenty, and recently earned the art-dealing community’s begrudging admiration by negotiating the sale of a Thomas Hart Benton mural to the Equitable Life Assurance Society. “No one had been able to sell them for years,’’ he says—again tooting his own horn.

His competitors grumbled when Janet announced to the world that his very first sale had been to the Getty Museum. The richest and most finicky museum in the world had purchased from the young upstart a rare work by the recherche Jacques Aved. But that was only the beginning. Next he discovered an early (1709) painting by JeanAntoine Watteau. He sold it to a Frankfurt museum. And when the German press discovered how much profit Janet had taken, he got a stack of clippings from Der Spiegel and other German periodicals denouncing him.

Then he purchased the set of panels by Benton, the famous American realist, from the New School for Social Research, in New York. He met the mayor. He gave press conferences. Some Australians wanted to buy the mural, but Janet, who says he loves America, had decided it should remain here. The negotiations with Equitable didn’t yield his usual million, but Janet became a regular feature in the New York Times.

The odds against finding a major old master have been put at 10,000 to 1. Janet, say those who follow the field, has the “eye” of his generation. Even Janet, looking much like a very prosperous Lazard Freres banker in pinstripes and collar pin, believes he has a special gift.

It may seem strange, but in a quiet moment, plumped on a red velvet Louis XV sofa in his East Side gallery, he says he has had these dreams. When he was eight, his mother, a Polish aristocrat related to the Radziwills, and his stepfather, the art dealer Francois Heim, took him to a gallery in Paris. From across a dark corridor, the young Janet pointed out a Rembrandt.

“I saw it in a dream,” he recalls.

His parents could not even focus on it.

“You know you are a born dealer,” he says very quietly, “when you wake up in the middle of the night with paintings spinning in your head.”

Jeffrey Hogrefe

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now