Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHEATER ACCIDENT REVISITED

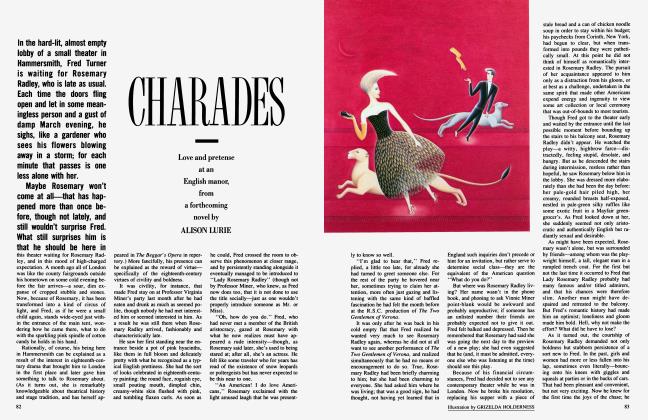

This month the master photographer IRVING PENN is being honored with a retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art. Theater Accident, left, published in Vogue in 1947, has always been one of his most intriguing narrative photographs. In tribute to Penn, we asked the playwright JOHN GUARE to consider what might have happened that night on Broadway

She falls asleep on the chaise.

The 1947 Vogue slips from her lap.

I move to slide her drink from its perch and, in so doing, step onto this page.

The lamp by the chaise creates a circle of light I cannot see beyond.

My bare foot covers the patent-leather pump.

I step into 1947.

New Look. Marshall Plan.

Collision.

Who is she?

Her clues:

The opera glasses. The gold. The cigarette holder. This is Broadway glamour.

(“A line in a column that links me with you.”)

Nineteen forty-seven.

This is definitely not a High Button Shoes crowd. Allegro? That was the smart show.

Rodgers. Hammerstein. Directed, choreographed by Agnes de Mille.

‘‘You are never away from your home in my heart.”

Note absence of ticket stub.

An escort has that.

But the taxi whistle—she’s used to traveling alone.

The pocket watch: 9:25. Not an intermission yet. Musicals began at 8:30.

She’s fidgeted her earring off during Act One. And that loose black pin—tugging a dark-brown strand free from her chignon. The scalloped pillbox with the Benzedrines and sleepers. A widow? A husband away? The remnants of war?

‘‘A fellow needs a girl to sit by his side at the end of a weary day, to sit by his side and listen to him talk and agree with the things he’ll say.”

She must get away from The Escort even for a moment. Flee up the aisle for even the length of this one cigarette.

(Streetcar is the hit of the season. Flight is in fashion.)

Nine twenty-five. Have I come in late? Or I’m searching a cigarette? Who do I flee?

The collision.

Collision in an empty lobby.

We’re both of a certain age. (Those are serious tortoiseshell glasses.)

I’m no Stanley Kowalski, but the collision around that comer packs its own wallop. I’m in my forties. (Bom late 1890s. Another century.)

“But now I’m face to face with you, and now at last we’ve met.”

She’s not fooled by the lyrics of show tunes.

And yet that single key is there. That gold pencil—to scrawl a destination?

“And now we can look forward to the things we’ll never forget.”

The lighter slides against my foot.

Distant applause. Intermission. The Escort will come looking.

I think of a woman more than a decade earlier whose second husband was killed in a motor accident upstate New York in Tuxedo Park. Escaping grief, she fled to California, where she married Number Three in a panic of desolation. Then left him the day after the marriage in San Francisco. Simply walked out of the St. Francis Hotel and got on a train to New York. Hid out. Weeks later, got herself dressed up, went off to the theater, and sat by chance next to my uncle, who had come there alone. They talked at intermission. (Is there anything more transient than an intermission?) They were together the next thirty-five years.

The Theater is the place where you seek out accident, take advantage of accident. Theater is the apotheosis of accident.

I look at the sleeping woman on the chaise. We met not in a theater but in one of those accidents of time and place that become translated into personal legend, inevitable geometry.

She sits up into the circle of light.

Nineteen eighty-four.

“Was I asleep long?” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now