Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

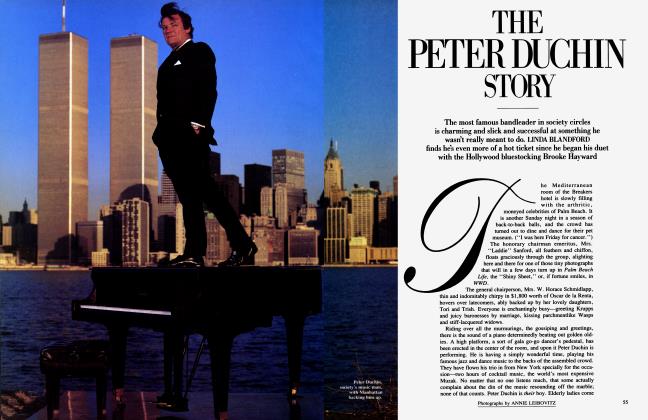

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOr how a modest Western, an uppity Oscar winner, and an unbridled budget brought down an empire. STEVEN BACH, head of worldwide production for United Artists in 1979, was there at the beginning of Heaven's Gate

June 1985 Steven BachOr how a modest Western, an uppity Oscar winner, and an unbridled budget brought down an empire. STEVEN BACH, head of worldwide production for United Artists in 1979, was there at the beginning of Heaven's Gate

June 1985 Steven BachWhen Heaven's Gate was first presented to United Artists in the fall of 1978, it was just another Western, budgeted modestly enough at $7.5 million. When it was finished, in 1981, it had cost almost $40 million, become Hollywood's new generic term for disaster, and paved the way for the sale of United Artists to MGM. Writer-director Michael Cimino and his producer, Joann Carelli, began preproduction on Heaven's Gate for a new and (mostly) inexperienced regime at UA just as Cimino's previous film, The Deer Hunter, went into release, arousing equal measures of controversy and acclaim and generating impressive box-office heat. Cimino's industry star was on a meteoric rise, and the budget of Heaven's Gate rose with it—not without approval from UA—as the director's vision and ambitions expanded to an ever more epoch-making epic. By February 1979, when this excerpt from Final Cut takes place, the budget of Heaven's Gate was $9.8 million and headed toward the $11.6 million official figure which UA would approve as "final" the day after The Deer Hunter won five Oscars, including two to Cimino for Best Picture and Best Director. Cimino's star had become a supernova, and so, said some, had his ego. But even before the Oscars there were portents that the newly flexing muscles of Hollywood's latest auteur could be very inflexible indeed, as even such fledgling executives as David Field, head of West Coast production, and I, head of East Coast and European production, could divine when it came time to cast the leading lady.

"Who the hell is Isabelle Huppert?''

Al Fitter, head of domestic distribution at United Artists, barked a half-laugh of disbelief as he mouthed the name he had never heard before. He was sitting on one of the new, creamy leather guest chairs in UA president Andy Albeck's office, a coffee cup balanced on one knee, a smoldering ashtray on the other.

Old Greenwich, Connecticut, was not ringing with the name, as David Field knew when he telephoned me the previous evening from California to alert me that Cimino wanted to cast Isabelle Huppert as Ella Watson in Heaven's Gate. We discussed it quickly. It seemed an aberrant and fleeting notion, and we resolved to humor him but withhold our approval, the right we had under contracts not yet signed. We were so certain we could handle this silliness that we briefly considered not even raising the issue with Albeck and the others. That finally seemed evasive. Our relationship with Cimino was too open and his industry status rising too rapidly not to mention the possible conflict in open forum, I in the room with the others in the daily production meeting, Field on the speakerphone three thousand miles away.

"Who the hell is Isabelle Huppert?" Fitter repeated, straining to keep his tone polite, the weight of his pendulous stomach drawing him forward in his chair. Albeck's face braced behind his owl-like glasses as his glance traveled across granite from Fitter's paunch and puzzlement to me for a response.

As the East Coast and European half of the team, I was presumed to know such things. Unfortunately, I knew Huppert only by reputation, and had never seen her on the screen. Were she a combination of Bardot and Bernhardt, however, it is unlikely my reaction (or Field's) would have been much different. She was a minor French actress with a flat, peasant-like face that was agreeable in stills without being notably pretty. Her performance in Violette Noziere had excited attention at Cannes, where she won the Best Actress award, but had not been widely seen outside France, and to the American moviegoer she was unknown.

Albeck pushed forward grimly: "What happened to Jane Fonda and Diane Keaton?"

"Unavailable," Field and I answered in unison, his speakerphone voice cutting out as mine rose in the room. The answer was technically correct, but sidestepped an issue we were not eager to scrutinize: neither Fonda nor Keaton had liked the script (or even read it, for all we knew), and anyway, neither would have consented to second billing after Kris Kristofferson, who had been contractually guaranteed first billing by Cimino. Both of these circumstances gave us pause, but not enough: a script disliked or unread by the very stars we needed to strengthen the box office, and a contract with an actor which precluded a strong female star because of its billing clause. The second problem was potentially easier, renegotiation being a way of life in Hollywood. As the producer father of Norbert Auerbach, UA's head of foreign distribution, once said (and Auerbach was fond of quoting his father), "We have to have a contract. What other basis will we have for renegotiation?"

Reactions to the script—or lack of interest in even reading it—seemed negligibly important, subjective responses. When had Jane Fonda and Diane Keaton (or their representatives) become critics anyway? The question seemed logical enough; most rationalizations do.

But not only Fonda and Keaton were unavailable or uninterested. Every acceptable Hollywood actress we had carefully listed under A was equally so, and we were increasingly hard-pressed to suggest alternatives agreeable to both Cimino and ourselves. He knew this and rightly rejected the B and C trial balloons as hardly satisfying the company's need for a major name. That he was right was small consolation, for having exhausted the ranks of the A's and excluded the lesser names, we made ourselves vulnerable to suggestions of unknown or little-known actresses who might be "right for the part." Like Isabelle Huppert.

The idea seemed so eccentric we wasted little time in debating Huppert's appropriateness for the role. We were more concerned with our ability to finesse Cimino in the delicate game of mutual approval, but we voiced our assurances to Albeck and the others that we could do so. For once, we were grateful for Distribution's protests (modified only by Auerbach's "helpful in the French markets" nod).

Field, now dealing daily with Cimino in California, correctly warned that we would need to give him a fair hearing, if only to preserve the appearance of tolerant appraisal; but we were both certain that persuasion and conviction—sensible, correct, and as unbendable as Andy Albeck's spine—would prevail.

The meeting continued with a discussion of whether we should or should not renegotiate the Scorsese-De Niro deal on Raging Bull, and what we would do with Francis Coppola's real estate if Apocalypse Now should fail.

"First of all, and most important," I began, "no one has ever heard of her. ' '

We were assembled several days later in Field's office in California: Field, Cimino, Joann Carelli, and I. Michael sat listening to our recitation of objections to his chosen actress. His responses, as always before, were measured and polite and as temperate as the February morning.

"With all the attention this film will generate, everyone in the world will have heard of her by the time we go into release."

"But, Michael, when we made this deal we agreed to Kristofferson because we shared your feeling that he could become a major star—' '

"And we still think so," one of us interrupted.

"—but the distribution people don't think he's a star and the exhibitors don't think he's a star and the critics don't think he's a star and the actresses we've gone after don't think he's a star. It was always understood that we would try to beef up the marquee with a commercially important woman, and we're only asking you to make this one concession— which helps you too as a major profit participant—to make this picture strong enough to earn back the ten or twelve million dollars we'll have to spend."

"Nine eight," Joann inserted.

'Ten or twelve. And for that we don't need Isabelle Huppert."

"One wants to be perfectly open," Michael answered evenly. "Tell me whom you have in mind who is available, affordable, and can play the part."

"There's got to be somebody we've overlooked. As of this moment we have no marquee other than Kristofferson."

"You've got Walken."

"If you recall, Michael, the reason you made the deal here instead of at Warner Bros, was that Warner's wouldn't accept Christopher Walken and we would."

"They would now," he said calmly. "They'll take the picture off your hands, and they know that Chris is going to win the Academy Award for The Deer Hunter."

"Tell Warner Bros, thank you very much and that Chris Walken's Academy Award won't make Isabelle Huppert a star."

After a pause Cimino asked, "Second of all?"

"What?"

"I've listened to 'first of all.' What's 'second of all'?"

"Second of all, she has a face like a potato," I said.

Cimino remained unemotional. "I find her attractive."

We were betting that Cimino would deliver a blockbuster with "Art" written all over it.

"Well, you're the only one, because no one else does."

Field winced. Carelli smiled to herself.

"How can you say that when you haven't even seen her on film?" Cimino challenged quietly.

"We told you we would and we will, but we can't conceal our concerns. There's no way we can get this past the distribution guys and Albeck even if we wanted to, and we don't."

There was a longer pause. I had done too much talking on what was Field's project, and I probably wouldn't even have been involved in the conversation had it not been for Albeck's October order that I spend one week a month in California. That and the mounting production estimates from Lee Katz, UA's production manager. Finally, Michael broke the silence.

"I'll go to New York and talk to Andy myself."

"That doesn't work, Michael," I said, not wanting him away from the work at hand and certainly not in New York. "We don't even know if she speaks English, for Christ's sake!"

"She speaks English."

"How do you know?"

"I've spoken with her."

A dreadful premonition took shape. He had spoken with her? About what? Certainly about the movie and the role of Ella, given his irrepressible energy. How far had he gone? Had he offered the role? Made a deal? They had the same agent; anything was possible.

Lately Cimino, with his Deer Hunter accolades, was not speaking idly. His readiness to go to New York and persuade Albeck sounded like a not very veiled threat to go over our heads and deal directly with the ultimate authority in the company. This would demonstrate that he was unwilling to bother with us any longer, and that we were trivializing UA's reputation with an already skeptical creative community. We heard his tone grow cooler than the morning, and he heard that we heard it. It was something new in our conversations with him, and it would not be the last time we would hear that chill.

But there was another, less self-serving reason we didn't want Cimino going to Albeck. If he had, indeed, already offered the part to Huppert, Albeck might feel morally obliged to honor that commitment, contractual violation (of unsigned contracts) or no. We had seen this happen more than once in the early months of Andy's presidency. Seemingly everyone in the movie business had been "promised" this or that by UA's previous regime. Many of these claims were hustles of dubious merit, but some were real and some were undesirable to the new regime. Albeck's policy was firm: a UA commitment, moral or otherwise, by this regime or the former, was to be honored, even if doing so were anathema to him for some business reason. At least one entire picture got made for just such a reason (Joan Micklin Silver's Chilly Scenes of Winter, also known as Head over Heels). It was a failure.

Whether Albeck's annoyance with Cimino if he had gone ahead and hired Huppert would have outweighed his sense of honor in this situation, we couldn't predict, but we didn't want to take the chance. Nor did we wish to raise, or face, the possibility that such a thing had happened. The better solution seemed to be to dissuade Cimino in a peaceable manner and go on to find another leading lady. We were confident of Cimino's reasonableness and undaunted by the absence of a single clue as to who that leading lady might be.

"Do you mean, Michael, that you've spoken to Huppert about the role of Ella?"

"Just generally."

That could mean anything or nothing.

"Didn't she find it odd that a French actress would be approached about playing a nineteenth-century Wyoming madam with an Anglo-Saxon name?"

"Why should she? She's an actress. Besides, almost everyone in this film is an immigrant, and another accent would only add to the richness of the sound track."

"Not if it's an unintelligible one," I said. "Michael, it's not your most brilliant idea. The answer has to be no."

Silence.

Cimino's round face betrayed nothing. Joann, who had remained silent, stirred on the nubby white sofa. A sharp nod of her head signified that for her, at least, a decision had been reached. Before she could speak, Michael replied, "I can't accept such a decision from executives who have never bothered to see their director's choice on the screen, who have never met or talked with her. You are rejecting her only because she doesn't have a name, no matter how right she may be for the part."

"What do you want us to do? We've tried to be open and honest with you about our feelings and our decision, and now you say you can't accept that?"

"First you could see her on film."

"We don't need to. You say she's great. Fine. We accept that. It isn't about that. It's about New York and the investment and the logic of that actress in that time and place and the language problem... Put all the rest aside for a minute and concentrate on that. If we agreed to reconsider her and used her English as the sole criterion, fairly and honestly, would you accept our decision after we talked with her?"

We wanted our very own epic, our very own hit, and we wanted Cimino. What we didn't want was Isabelle Huppert.

Carelli's eyes were roaming the ceiling. Cimino asked, ''You'll go to Paris?"

''No," I said. ''But I went to school there and speak the language. Have her telephone me, and we'll talk for a few minutes. If I can understand her English over the phone, I'll remove my objections, and David can do what he wants." This was much less generous of me than it sounded. Huppert's agent in Rome, who was by chance my houseguest in Los Angeles at the time, had already informed me that she spoke English only haltingly and with an impenetrable accent. "I still don't think New York will buy it, but we want to be fair. If I can't understand her English, we can speak French for a minute and I'll get out of the call without embarrassing you or her."

Michael considered, nodded. ''When do you want her to call?"

''Whenever. Make it easy on her. But, Michael, it's understood that if the decision is no, it's final?"

He nodded.

Isabelle Huppert telephoned from Paris to my Los Angeles number the next morning. I didn't understand one word of English she spoke, and the only part of her French that I remembered clearly after the conversation was the part about how thrilled she was to be playing the role of Ella.

Field and I met in his office an hour later.

"We have to say no and we have to mean no. It's going on too long. It's bad for the movie; it's bad for our relationship with Michael. If we capitulate over this issue, it's bad for us in the company, because I don't know how to justify this kind of wrongheadedness, and if we don't say no now and mean it, he'll have us on a goddamn plane to Paris to meet with her!"

David nodded. ''Let's call and tell him no. Nobody's going to Paris."

The Concorde landed at Charles de Gaulle at 10:40 on a drizzly Sunday night in late February. David and I were met by Jean Nachbaur, the friendly head of the Paris office of Les Artistes Associes, as UA is known in France. On the way into town we made halfhearted small talk, which failed to lift my gloomy resentment at having agreed to make this trip at all.

Field and I had had ample time to reflect on the events of the past few days and had discussed the issues of casting and our relationship with Cimino fully and candidly with Albeck. Andy was anything but peremptory regarding this trip to meet Huppert and hear her read with Christopher Walken, who had flown from New York ahead of us with Cimino and Carelli. (The three of them had to be in Paris on a public-relations tour for The Deer Hunter.) Andy viewed it as an expensive but desirable demonstration to Cimino that we were prepared to extend ourselves far beyond the usual limits in considering a serious creative request. Still, there was little doubt in my mind or Field's that we left J.F.K. charged with delivering a swift and final no to end, once and for all, l'affaire Huppert.

We had said no to Cimino in California, and we had meant it. Michael pressed all his arguments, which were neither inconsiderable nor unreasonable. Flying to Paris for one last meeting seemed excessive, but I had Moonraker business to conduct there and was eager to see the final print of La Cage aux Folles in its French dubbing. For Field, the trip was more arduous, but at least it was a respite from the often crushing California schedule.

We settled into the Plaza Athenee and had a drink. We knew this trip was a showdown on both sides (Would UA cave in? Would Cimino take no for an answer?), and each side was undoubtedly investing the issue with a higher degree of urgency and portent than it warranted. The fact was that never before had we seriously challenged Cimino in the creative area. No one had indulged him, but no major difference of opinion had surfaced either. We admired his work and enthusiasm and believed his perfectionism deserved the most thoughtful response we could give. At the same time, we did not want to be bulldozed. Our reasoning, we told ourselves, was commercially responsible and politically smart within the company.

Still, there were crosscurrents. The commercial reasoning was easy to state and obvious to any film major at U.C.L.A. Perhaps it was too easy and was too obviously stated and restated by the distribution people, for whom our esteem was low and continuing to deteriorate as defense against their involvement in just such decisions as this. In some subtle way, in fact, the more crudely expressed and aesthetically indifferent the Distribution opposition became, the more necessary it seemed to weigh the nuances of Cimino's arguments in terms other than the purely commercial. We needed to shift the focus from their arena to ours. It was as if being pressed to back Distribution in a "Who the hell is Isabelle Huppert?" position—which we had, in fact, formulated ourselves—furthered their ends, not ours. In an internal political sense, this could only further erode what little real creative autonomy we felt we had in the company to begin with.

Another complication was that we liked Cimino and thought UA needed him, or his current celebrity and heat, at any rate. The relationship was too new to be other than cordial and mutually supportive, we thought, and we wanted to keep it that way with standards of behavior as high as those we hoped he would bring to the film. In short, we wanted our very own epic, our very own hit, and we wanted Cimino. What we didn't want was Isabelle Huppert.

We gathered together in Michael and Joann's Hotel de Crillon suite shortly before midnight. Chris Walken, whom I had known casually for some time, was seated on a stiff-backed French sofa next to what appeared to be a thirteen-year-old redheaded gamine. I revised my opinion: she didn't have a face like a potato, after all; she looked like the Pillsbury Doughboy got up in a shapeless cotton shift. Nothing about her quite registered. Her hair, her face, even her freckles were pale. Her features lacked definition and seemed padded with puppy fat. She was tiny, she was lumpish, she made no particular effort to be charming, and whatever hopes I might have secretly harbored that one look at her would thrill me and change my mind and the direction of this dilemma sank like stones. International stardom couldn't have seemed more remote.

We made awkward small talk with Walken, Cimino, and Huppert while Joann ordered white wine and grapes from room service. As we talked, it became apparent that Huppert's English was indeed better than it had sounded over the telephone. Cimino had claimed the call intimidated her, causing her to freeze in a language not her own. Still, her command of English that night was only serviceable, and her accent, while charming, was pronounced and often obscured meaning. It was, moreover, clear that she didn't have a clue who we were or why we were there.

The room-service waiter came and left, and after pouring the wine, Michael quietly handed scripts to Walken and Huppert and suggested a page on which to begin, and after a moment of study, they did.

Christopher Walken has always seemed to me an exceptional actor. I first saw him perform Off Broadway in Thomas Babe's Kid Champion in the mid-seventies, and I had followed his career in Sweet Bird of Youth and a few movie appearances before The Deer Hunter. He had a haunted quality that could turn quickly sullen and dangerous, and his talent and lopks might have made him a major actor long since, I thought, were it not for a certain reserve about him, almost a secretiveness, which deflected attention. Maybe it's an actor's trick, I thought, remembering De Niro and Woody Allen. But Walken's recessiveness was entirely absent that midnight and early morning. He was low-key but playful in his reading, young and even engagingly silly at times. Clearly he was there only to help Huppert feel at ease, and I suspected that Cimino, to whom Walken owed a great deal after The Deer Hunter, had coached him into making this reading very warm, very charming.

Cimino sat silently with us and listened, interrupting only now and then to suggest a different mood or a different scene, his direction so quiet as to seem whispered. If he had actually rehearsed the two, he had done a good job with Walken.

Huppert was une autre histoire. She read indifferently. Her reading English was less good than her speaking English, stilted and more heavily accented. She seemed to have little idea of the script's content as a whole and none whatever of the character of a frontierswoman in nineteenth-century western America. I had conducted or been present at many such readings in the theater and films, and while the process is terribly deceptive and unreliable, there was nothing here to make me feel Cimino's decision was justified. She was too young, she was too French, she was too contemporary, she was too uncertain in her reading. She was simply wrong.

Still, as the night wore on and the wine bottles emptied, her charm began to take hold. Her short, stubby child's fingers darted here and there, brushing the hair from her eyes, tapping the script in sudden understanding, toying with the pale-green grapes when confused, taking on a quality of grace not initially apparent. She curled her legs under her on the sofa and showed off her figure, zaftig but good. Her eyes seemed to collect light as the night deepened, and her laugh had the lilt and spontaneity of a particularly happy puppy. The word that came to my mind and would not leave was adorable. I began to find her captivating and charming and pretty, but never for one moment did I see her as Ella Watson.

Had we been struck down by a runaway taxi on that walk, there might be a United Artists today.

Cimino was too perceptive not to have known that our reactions were negative. Nevertheless, everyone agreed to defer conversation until dinner the following evening.

Field and I returned to our rooms around three o'clock in the morning, fatigued by the flight and unsettled by the results of the reading. We hadn't wanted her to be perfect, and she wasn't, but everything might have been easier if she had been.

The line between rationally weighing alternatives and rationalizing them is notoriously fine. Field and I were a good team most of the time because most of our perspectives were similar. When they were too similar, we often had the resoluteness that comes easily when talking to oneself. We were both, by background and temperament, given to aesthetic hairsplitting and impressed, I think, by our "sensitivity." Without sensing the pretentiousness of it, we were convincing ourselves that our superior and subtler understanding of the creative process had some moral force that would not only sway Cimino but render Distribution's position—whatever it might be in whatever instance—beside the point. In this way it began to seem preferable and somehow nobler to make the wrong decision for the right reasons than the right decision for the wrong.

It was clear that Huppert had appeal. Certainly she could substantially improve her English in the weeks that remained before shooting began. Cimino could, and no doubt would want to, rewrite the role to fit whatever actress was chosen to play Ella Watson, which could minimize (though never obliterate, I felt) the incongruities of Huppert in that role. Finally, there was always the possibility that Cimino was right, that he saw something in her our vision was not acute enough to see. Kristofferson wanted her (we were told this, though the fact that he, Huppert, and Cimino all shared the same agent might have prompted skepticism); Walken seemed to want her; Cimino strenuously wanted her. While these arguments were germane, they did not add up to that sudden "yes" of inevitability.

The more urgent argument was that, after months of trying, we had come up with no one else. We had been through scores of names after the initial turndowns by Fonda and Keaton, and during the months of searching it is possible we unconsciously resigned ourselves to having a minor or new name in the role by default. Surely, however, there were American unknowns who could more easily slip into Ella's frontier muslin and gain the approval of the New York office.

If we crossed the line between rationalizing and rationale that night, neither of us knew it. Certainly we did not do so with regard to Huppert's suitability for the role. If we crossed the line, it was in the area of excessive and vain (in both senses of the word) concern over how our handling, or failure to handle, Cimino would be viewed by the Hollywood community, by our colleagues, and by Albeck. We agreed to sleep on it, each knowing the answer would be no but not knowing what would follow.

Michael and Joann met us the following evening at Le Coupe Choux in Beaubourg near the Centre Pompidou. The setting seemed right, the atmosphere candlelit and congenial, the tables casual and pretty, the food unpretentious and good. The restaurant is often frequented by Parisian show-business people, which meant one could talk, drink, and eat well without a tourist crush. A simple, undistracted dinner among friends.

We ordered some wine and avoided the subject of Huppert. I filled the others in on my day at Studios de Boulogne, where Moonraker was finally finishing months of production. We had hoped in June to contain the picture's cost at twenty million, but it had gone beyond thirty, a figure I was not about to raise here and now, and there was still unpredictable and costly special-effects work remaining at Pinewood, including one very difficult effect which necessitated exposing a single strip of negative forty-eight times, rather than resorting to lab work and optical printers. A mistake or miscalculation in any one of the forty-eight exposures would have destroyed hundreds of costly hours of effort. Happily, it worked.

The conversation ranged over this and over the general necessity of controlling budgets, and certainly the verbal nudges were less than subtle. Whatever urgency I tried to convey about budget concerns was muted by the assumptions everyone, including UA, made regarding Moonraker: James Bond couldn't miss. (He didn't. Moonraker went on to become the biggest box-office success in the history of that remarkable series. Until the next one.)

Finally, over espresso, the reason for our visit could no longer be avoided. Gently but firmly we traced the history of this situation, pointing out that we had been negative from the beginning, had said no more than once, had agreed repeatedly to re-examine the question, always with assurances from Michael that he would abide by our decision, and had made the extraordinary gesture of flying halfway around the world to listen to a reading in a hotel room in the middle of the night. The answer was still—unequivocally, finally, and forever—no.

Though Cimino was normally quiet, he fell now into a silence that suggested glaciers and frozen wastes. His ruddy face seemed to darken in the glow of the table candles, and his eyes to contract to pinpoints. Ill at ease but determined, we struggled through his silence, detailing our reasons, turning now and then to Joann, who agreed with a matter-of-fact "Right" at almost every turn, a surprise event that seemed to turn Cimino to stone.

At last he spoke, his voice quietly poisonous. He accused us of bad faith; he accused us of cowardice regarding New York; he accused us of insensitivity and lack of aesthetic judgment. He rejected us as corporate executives; in tone and manner he rejected us as human beings. Finally, he announced it would be impossible for him to make the picture for people as insensitive and untalented as ourselves, and he would instruct his representatives to move the picture from UA to Warner Bros.

We had heard this threat only days before and would hear it again, but at this moment, if he was bluffing, he was persuasive. Whether he could actually move the picture we didn't know, but it seemed likely. Warner's had been romancing him for months, and the interim reception of The Deer Hunter might have overcome the company's earlier objections to Walken. Who knew? Warner's might even accept Huppert without argument and prove us not only incapable of keeping a major filmmaker at UA but aesthetically wrong in the bargain. Still, we were being bullied, and I resented it and the position we were being placed in. I shot off my mouth: "For Christ's sake, Michael. Kristofferson and Walken are so much more attractive than she is that the audience will spend the entire film wondering why they're fucking her instead of each other!"

My timing was not good. Instantly David kicked me sharply and painfully under the table. Michael was paralyzed for a moment, then loftily looked away in baleful silence, as if he had changed planets. Joann feebly mumbled something she meant to agree with my general point, but the damage was done and dinner was over.

We separated coldly, Michael having washed his hands of us, Joann uncomfortable about her own candor, David and I roiling with frustration, resentment, and anger. Walking back to the hotel through the wind-whipped chill, I turned to David and asked why he had kicked me so forcefully under the table.

"Don't you get it?" he asked. "He must want Huppert because he's infatuated with her."

"What about Joann? I thought they—"

"Not for years. Don't you see? It's the only thing that makes sense."

Whether there was then, or ever, a romantic liaison between Huppert and Cimino we were never to learn or care about. Such things are not unknown, but Cimino was beginning to strike me as far too obsessive a careerist to allow an emotional attachment to jeopardize any aspect of his professional life. In any case, if David's shot in the dark was correct, the situations were not mutually exclusive and even had a little old-time glamour: Stiller and Garbo, von Sternberg and Dietrich. We dropped the subject, and, as far as I know, it was never brought up again. We had other matters to reflect on that night.

We had blown it. We had blown the picture, the relationship with Cimino (whatever it was), maybe our reputations in Hollywood, both personal and professional, probably any credibility we might have had within the company, possibly even our jobs.

What had we gained? Even if the picture were to stay at UA for legal or other reasons, Cimino would certainly veto vigorously any casting suggestions we were likely to make. And how justify to him a littleor unknown American actress after having turned down Huppert, who at least had some critical cachet?

Working with Michael could turn unexpectedly ugly very quickly; he had demonstrated at the dinner table that he was prepared to jettison the relationship with United Artists to get his own way. How then were we to win his confidence or cooperation during the actual making of the picture? Or had we unintentionally rendered the picture unmakable because uncastable? Millions of dollars had already been spent or committed; what of that investment? Finally, one central issue emerged from the anxiety: did we want the picture badly enough to take Isabelle Huppert with it, with all that that might mean in terms of the relationship with Michael?

Had we been struck down by a runaway taxi on that walk back to the avenue Montaigne, there might be a United Artists today. Instead, we arrived safely at the hotel, had a nightcap, and placed a transatlantic call to Albeck in New York.

Andy listened stoically to our recitation of the events leading to the call. We didn't spare ourselves. We admitted we had been guilty of naively underestimating Cimino's resolve and overestimating our own manipulative skills. Andy's questioning was careful and sensible; at the same time, he was relying on an analysis he had to take on faith, having no practical experience in such situations himself. He was as realistic as could be expected; understood that artists were often demanding and difficult; was keenly aware of the moneys already invested and, I think, unshakably determined to prove to Transamerica, UA's parent company, and to Hollywood that the "new" United Artists could deliver major pictures as well as anybody else. Still, Isabelle Huppert would mean even less to John Beckett, the chairman of Transamerica, than she had to Al Fitter.

Then it came, the masterstroke of persuasion and manipulated perspective: Who was the real star of this picture? Not Kristofferson, who couldn't carry it alone; not Fonda or any of the others we couldn't have anyway; not Chris Walken or the secondary actors Michael wanted. The star of this picture—it was so clear—was Michael Cimino. We weren't betting that this or that actor or actress would add a million or two to the box office. We were betting that Cimino would deliver a blockbuster with "Art" written all over it, a return to epic filmmaking and epic returns.

Yes, Cimino was the star, we argued, and if he wanted Huppert, we had an obligation to back him. He was the director. Perhaps we were making the wrong decision for the right reason even then. We probably thought so.

Perhaps some less enlightened or more hotheaded production executives at another studio might have told Cimino to go fly a kite and thereby saved their company $40 million and its very existence. But, in what was perhaps the most naive and seminal delusion of all, we believed that now that we knew Cimino's darker, colder side we could better handle him in the future. There was precious little prescience in Paris that night.

The next morning we capitulated.

Isabelle Huppert would play Ella Watson.

Steven Bach's bode, Final Cut, from which this section is excerpted, will be published next month by William Morrow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now