Sign In to Your Account

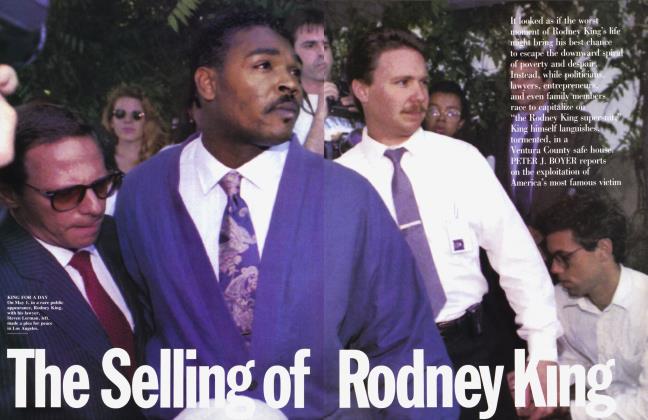

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEarth Angel

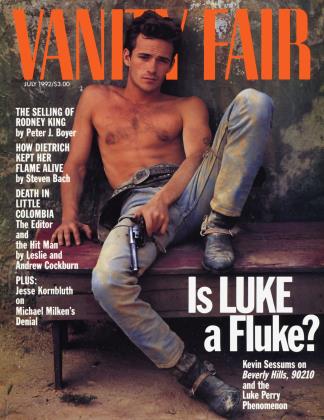

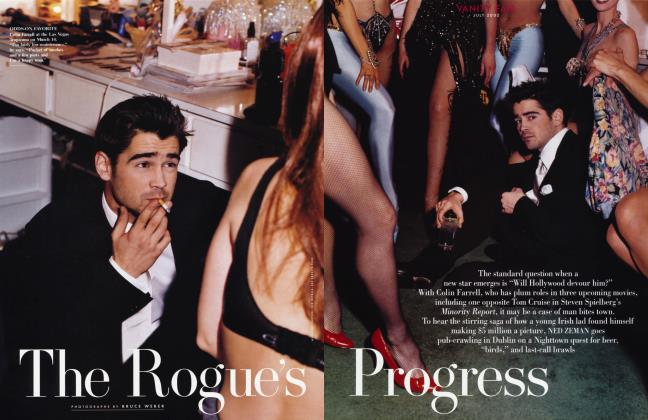

She claimed to be bored by her illustrious past, but Marlene Dietrich was really the greatest keeper of her own flame. STEVEN BACH spoke with Dietrich extensively in the last years of her life, and in this extract from his upcoming biography he reports how her brilliantly daring mystique endured, even where lovers and mentors did not

STEVEN BACH

'It's Marlene," she would say, when I picked up the phone, in that voice Hemingway said could break your heart. It was 1986, and the heartbreaker as she edged toward ninety was that it had become as brittle as parchment. But you could still hear the technique. She was still an actress, still made that little dip in the second syllable (''It's Mar-/ay-na") that had made knees weak for half a century.

Ill and old, a proud recluse, she had only the telephone to connect her to the world from her bedroom on Paris's Avenue Montaigne, just across from the Hotel Plaza Athenee. She was determined to remain ageless, guarded from photographers and biographers who might try to plunder or diminish Dietrich's Dietrich. She knew I was writing a biography of her and was therefore a danger; she gave me the time of day only because I had known Josef von Sternberg, who had catapulted her to world fame. She also knew I could help her with some business.

She wanted to sell her famous stage costumes, those confections of stardust-and-nothing which had knocked eyes out from Las Vegas to Moscow to Tokyo all through the fifties and sixties, right up to the fateful fall in Australia in 1975, when her body broke apart onstage and ended the greatest of her careers.

She had read Final Cut, a book I had written about some broken bones of my own, sustained in the movie business, and she called to say she liked it, adding, ''You got the editing part wrong." She explained, ''It's all, all, all in the editing!"—as good a definition of the Dietrich legend as I had ever heard. ''And the angles," she continued with a chuckle. ''There's always an angle. What's yours? What's an American doing living in Germany anyway? Germans have no sense of humor. ' '

''You do," I answered.

"I'm not a German!" she boomed. "I'm a Berliner!"

She still had the Berlin sense of humor and the Berliner's vital concern about the world and what its view of her might be. Selling her costumes for ready cash didn't go with the legend, and she had a horror of pity, but she was broke. Her Belgian landlords had repeatedly and publicly tried to evict her, but the French know a thing or two about public monuments and had picked up the rent for this Commandeur de la Legion d'Honneur. When I offered the famous "diamondstudded gown" and swansdown coat (hand-mended by her) to the Metropolitan in New York, she was appalled, fearing someone might think of her as a "museum piece." That was better, though, than putting them on the block at Christie's or Sotheby's, who printed catalogues. Her jewels were one thing (some went up for auction in 1987), but she didn't want "my old clothes," as she called the costumes, to be treated like dirty laundry.

I finally found a buyer willing to pay $25,000 for the dress and coat she and Jean Louis had invented together, and she never asked who bought them. I was just as glad, because I wasn't sure how thrilled she'd have been to learn they had been purchased by the German Film Foundation in Berlin with money provided by the Berlin Senate. It was a first gesture of the reconciliation that is only now—now that it's too late—taking place. Lili Marlene's entertaining Allied troops as they defeated the Nazis would never quite be forgiven. She forgave them for not forgiving her, in the end, by asking to be buried in Berlin, next to her mother.

"Iam ready to sell my soul for money!" Dietrich told me when I agreed to help her. The money didn't go to her directly, but into a joint account in a New York bank, an account hard for her to draw on from the bed she could leave only with the aid of a walker or a wheelchair. When I asked her if there were other items I could help her sell, she exploded. "I am astonished that you think—you who know the business— that I would have here in Paris or in my home in New York any 'memorabilia' from my films. Do you really think that I schlepp around with me props and things I stole from Paramount? Anything used in my films was conscientiously returned at the end of each day!"

She never admitted that she couldn't walk, that she couldn't do what she liked to call "the Dietrich strut" anymore. Anything less than perfect health didn't go with the legend. Or with those legs. A very Dietrich-sounding maid often answered the telephone in a funny accent and explained, "Miss Dietrich is lunching at Versailles," or "Miss Dietrich is driving to Zurich," or "Miss Dietrich is on a plane to Tokyo."

One day she confided to me how she outwitted the nosy world by only pretending to be a recluse. "I keep my car in the garage of this building," she said, forgetting she had never learned to drive. "The elevator takes me directly to the garage, and I get in my car and drive to the airport in sunglasses with a scarf around my head. That's why photographers who hang around the building never see me. Do they think I go in and out the front door? When I know they're waiting? I'm not meshuga!"

We agreed that I would come to Paris to pick up the costumes. On the appointed day, I checked into the Plaza Athenee, sent over some flowers, and called. "Miss Dietrich," I was informed, "is lunching at Versailles."

The next day, when I was back home in Munich, a thousand miles from her, she called. "It's Marlene, schweetheart," she said with the familiar lisp. She scolded me about the flowers. "They die and drop petals on the piano, and then I have to dust. Besides, I don't want you spending money on me. I hate waste." Hausfrau Marlene, thinking of economies. She used international telephone as her personal wire service, and also sent notes, invariably printed in inchhigh letters with red or green ink. An inveterate reader, she had friends in Tarzana, California, buy glasses for her at the comer drugstore that her Paris doctor wouldn't prescribe over the phone anymore.

Reading was vital—newspapers, magazines, books. She wanted to know what was going on in the world. She called me one night in 1987 and said, "I have nobody of intelligence to talk to. That's why I'm calling. I want to talk about Chernobyl." The French trial of Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie, "the Butcher of Lyons," the same year outraged her, because the French seemed not to care. She was incensed that her secretary, a Jewish woman from Chicago named Norma, didn't seem interested. She railed at the same time she wished she could forget. "I shouldn't let it eat me up like this," she sighed, but forgetting was hard for the woman who had turned down Hitler and his cronies. ''I went through Belsen," she told me, ''and I saw it all. The smoke was still rising from the chimneys. How can they forget Auschwitz?"

She thought nothing of standing nine hours without a break as costumes were literally built on her body.

"Women are better," she would say. "But you can't live with a Woman."

When six-and-a-half-year-old Maria arrived

in Hollywood, Marlene announced she was four.

Bacharach let hr croon, he let her belt,he let her purr.

She called Nazi-hunter Beate Klarsfeld to discuss the Barbie case, and brooded that her Jewish secretary sensed no irony that Rudolf Hess, the Fiihrer's deputy, was then seemingly as fit as a fiddle as the sole prisoner in Spandau. ''1 met him once," she told me. ''He was the least—how do we say that?—coupable, because the most crazy." She decided ''they must have the best food and medical care in the world at Spandau," and asked Klarsfeld facetiously what you had to do to get a room there. ''Kill a Jew," said Klarsfeld. "Oh, Norma!" Dietrich called out.

She chose to forget I was writing about her. She had written her own memoirs, a small masterwork of evasion that so angered British critic Gilbert Adair that he titled his review "Witness for the Prosecution." She had written it in English, but it went through German and French before it traveled back into English from someone who never saw the original (I did: it was better than anything that ever got printed). When it was published in America, Stephen Harvey of the Museum of Modem Art reviewed it for The New York Times. Dietrich wrote to tell him she had written it in German, she had no idea it was being published in English, and he had gotten it all wrong anyway.

She knew I was traveling to Paris, London, Berlin, Prague, Brussels, Copenhagen, Vienna, Moscow—anywhere there were prints of those films she "never ever made" before The Blue Angel. She seemed not to care, but always managed to track me down by telephone wherever I was. She still claimed she had been "a student in a theater school" when Josef von Sternberg came to Berlin to make the movie that would make her famous forever, and none of those old nitrate prints I was watching on rusty moviolas or in dank Iron Curtain archives existed for her, so she pretended they didn't exist for me.

But they did, and I saw them, and what I would like to have told her before she died on May 6 was that the legend had maybe edited out too much. The more I realized the cost of building the legend and maintaining it, the more I believed the life made the legend bigger, not smaller—made the woman more than just a myth.

She had always insisted on keeping private and public lives distinct and separate. It wasn't so much that they were different; they often weren't, but insisting they were was her way of surviving Dietrich. The film roles were yesterday's news about today's woman. They reduced her to a few hours of shadows. Dietrich's Dietrich was always now—present tense—not reducible to anything; it had already been pared away to its essence.

I mistakenly thought that time had passed her by in reclusion, that her loyalty to her own image had made her out-of-date. Then she told me that Madonna wanted to remake The Blue Angel and was asking for a personal interview in Paris. "I acted the vulgarity," she trumpeted. "Madonna is vulgar!" I was so surprised by the outburst that I asked whom, if anyone, she saw in the part. "Tina Turner!" she answered like a shot. "I love Tina Turner!"

(Continued on page 152)

(Continued from page 93)

The first time I saw The Blue Angel was at the old Cinematheque Fran$aise in Paris. In the audience was a small, inscrutable-looking white-haired man. I was a student, and he, Josef von Sternberg, of course, had made the picture, which sent Marlene Dietrich into orbit. The next time I saw the film, I was also with Sternberg, but now I was his student in California, writing a Ph.D. dissertation on the seven astonishing films they made together. I saw all seven with him, and listened to the bitterness in his voice as he informed me, "I am Miss Dietrich. Miss Dietrich is me."

I spent long hours with him in his garage in Westwood, which he had converted into a library-den that was a kind of personal shrine. The walls were lined with hundreds of books, each with a little blue piece of paper marking mention of him. He loved to take them down and read them aloud—the more viciously dismissive they were of his great career, the better. It was his way of proving to an admiring student that he had survived his critics and somehow survived the woman whose huge blown-up photographs filled the space between the bookshelves and the ceiling. They were the most beautiful photographs 1 had ever seen of Marlene Dietrich, each one inscribed "Without you I am nothing" or "You god, you" or "From the creation to her creator."

I knew even then it wasn't that simple. If there was a single great love story in offscreen movie history, this was it.

In 1929, Josef von Sternberg was in Berlin, looking for an actress who could make believable the degradation of a respectable bourgeois professor played by Emil Jannings, then considered the greatest dramatic actor in the world—and do it with a song. It was vital that she be able to speak English as well as German, so that the film we now know as The Blue Angel could be certain of the American market. The search for Lola-Lola, as she was called, would be equaled only by David O. Selznick's search for Scarlett O'Hara a decade later.

Sternberg had seen and rejected virtually every actress in Berlin. One he had not seen, because she was in rehearsal for the biggest musical of that season, he would see almost by accident, because two other players in the musical had already been signed for his film. The musical was called Two Bow Ties, and he went to see it with everyone connected with the picture, but without his wife, who had accompanied him to Berlin for their second honeymoon, and who remained in the hotel because she did not understand German.

As it turned out, the leading lady of the musical played an American dollar princess, and almost the first line she spoke, announcing the number of a winning lottery ticket that set the plot in motion, was in perfect English: "Three—and three— and three!!—Three cheers for the gentleman who has drawn the first prize!" She acted vaguely bored, and she was elegant but louche, with heavy-lidded eyes and a musical, throaty voice.

As Sternberg watched the play that night (he would forever after dismiss it as a "skit"), what he saw and heard changed film history and his life. What he said when his colleagues turned expectantly to him to gauge his reaction was "What? That untalented cow!" But what he dreamed was Marlene Dietrich.

When she appeared for the audition she would claim she never cared about, some intuition may have told her she already had the part. She was almost brazen with affected indifference, perhaps because she saw herself in ingenue roles of the sort Elisabeth Bergner had become the rage in. (Bergner knew this, and her silky response was "If I were as beautiful as Dietrich, I wouldn't know what to do with my talent.") She told Sternberg she photographed badly, got bad press, had made three films and was no good in any of them. Sternberg wasn't entirely taken in. He thought she had made nine pictures (it was twice that many). The show he had seen her in the previous evening was her twenty-sixth theatrical production. Moreover, she was a twenty-eight-year-old wife and mother.

Her husband was a thirty-two-yearold man-about-town and production assistant named Rudi Sieber. Their open marriage was common knowledge in Berlin, where Marlene had acquired— and kept—the sobriquet "the girl from the Kurfurstendamm," in spite of having been a mother since late 1924. When her daughter was little more than two, Marlene had left Berlin to follow matinee idol Willi Forst to Vienna, where she worked in theater and films and turned down young Otto Preminger's entreaties to leave Rudi for him.

She had returned to Berlin instead, and created a sensation singing a lesbian duet (which became her first recording) onstage in It's in the Air, the hottest ticket in Berlin in 1928 until The Threepenny Opera demoted it to number two. She was also a ubiquitous figure in Berlin's gay bars, perhaps because her husband had become involved with a Russian dancer named Tamara Matul, with whom he would spend the rest of his life.

When Sternberg said he wanted to test her, she agreed on the condition he see the three films she admitted to, and added gratuitously that she had seen his films and didn't think he knew how to direct women anyway. This was as breathtaking and brazen and insolent as Lola-Lola herself would have to be. He saw her films and knew he had been right, but to establish who was puppet and who was puppeteer, he insisted on making a test. She arrived showily unprepared, without costumes or music. Sternberg called for a pianist, pinned her into a spangled costume, frizzed her hair with a curling iron, and let her sing for his cameras. "She came to life and responded to my instructions with an ease that I had never before encountered," he said later. "Her remarkable vitality had been channeled."

So had his aesthetic attention and romantic obsession. Marlene never even asked to see the test. She knew. The picture—the most expensive sound picture yet made anywhere in the world—was meant to be a star vehicle for Jannings. Scenes were shot first in German, then in English, and the effort for Jannings sometimes showed. Marlene had fewer problems, because she had already made recordings and understood the microphone. Sternberg allowed her to use the full range of her voice, the full wattage of her personality. His filming of her song sequences was shrewd; he mostly turned on the cameras and let her perform. She knew what she was doing and needed only a setting and an audience, and everybody from Buster Keaton to Max Reinhardt dropped by to hear Emil Jannings talk and stayed to hear Marlene sing. Something was happening on Stage Five at UFA, and everybody in Berlin wanted to see it for himself. The day Leni Riefenstahl arrived with a director friend, Arnold Fanck, Sternberg was shooting Marlene singing "Falling in Love Again." At one point he screamed, "You sow! Pull down your pants; everyone can see your pubic hair!"

The premiere, on April 1, 1930, remains one of the most memorable nights in screen history. She went directly from her ovations on the stage to the boat train to Bremen, and set sail for America, still wearing the gown in which she had taken her bows. She sailed alone, leaving her husband and daughter behind.

She may have been the first woman in the world famous for being famous. Before her ship docked in New York, Paramount had started erecting billboards bearing nothing but her photograph and the words MARLENE DIETRICH—PARAMOUNT'S NEW STAR.

She was introduced to A-list Hollywood by Paramount production head B. P. Schulberg at the Beverly Wilshire hotel, at a party to celebrate the engagement of Schulberg's assistant David O. Selznick to Irene Mayer, daughter of Louis B. Irene Selznick remembered, "There was suddenly a silence, a suspended silence.... Then these high double doors at the end of the ballroom opened and in walked Marlene. No one had ever laid eyes on her before. She entered several hundred feet into the room in this slow, riveting walk, and took possession of that dance floor like it was a stage. It was something out of a dream, and she looked absolutely sensational."

She also looked absolutely sensational in Morocco, her first American picture, released in this country before The Blue Angel. Sternberg subjected her to dietary and physical training with groomers, ineluding Sylvia of Hollywood, who claimed to massage away not only fat but cartilage too. He supervised a makeup makeover by Paramount's Dotty Ponedel, who elevated and winged Marlene's eyebrows, lengthened and darkened her upper lashes, and drew a white line along her lower eyelids to "open" her eyes, making them seem larger and drawing attention away from the "Swanson," or "duck nose," that had always bothered her, on which Ponedel drew a fine silver line that caught the light and "straightened" it.

The transformation was more than skindeep. Sternberg shook her free of the notion that she was anything like an ingenue, and his personal feelings for her focused the femme-fatale component. She not only liked it—she lived it. Not surprisingly, Mrs. Josef von Sternberg noted this and filed suit for divorce on the grounds of alienation of affections. Marlene's own affections by then, however, were directed not at Sternberg but at her Morocco co-star, Gary Cooper, which did not go unnoticed by Sternberg.

The publicity about Paramount's new love goddess was packing them in all over the world. So was speculation about Marlene's private life, aroused by the most startling scene in Morocco, in which, dressed in top hat and tails, she kisses another woman full on the lips. Sternberg understood and exploited Dietrich's androgynous, even bisexual, appeal by having her take a rose from the woman she kisses and nonchalantly toss it to her leading man. There was nothing accidental about this. Sternberg knew from the time he had spent with Marlene in Berlin that she welcomed admirers of both sexes, and that some of her liaisons had in fact been quite notorious. Paramount's having trumpeted that she was also a loving mother tended to undercut the implications of the top hat and the kiss. It also confused observers, who wondered about the true relationship between "Svengali" and "Trilby," as the press insisted on calling Sternberg and Marlene. It didn't confuse Sternberg's wife, who announced, "He is madly, heart and soul, in love with her!" He was not alone, said Lupe Velez, Gary Cooper's fiery paramour. Sternberg's re-creation of Marlene from plump, rowdy Lola-Lola into the elegant siren who follows Gary Cooper barefoot into the desert was so successful that even Louella Parsons said, "There is a definite likeness to Greta Garbo, although Miss Dietrich is prettier."

Miss Dietrich also could sing, had legs, and was not in the least reclusive. The socalled Garbo-Dietrich rivalry was never much more than a Paramount-MGM rivalry. Sternberg's greatest contribution to Dietrich's screen image was to convince her and audiences that she was unique. No rival—not Bergner, not Garbo—could compete with the exquisitely beautiful seductress he saw in her, and he knew that if he could convince her of that her ferocious ambition would do the rest.

Morocco's release was followed in America by The Blue Angel and Dishonored, their third collaboration—all within four months, a one-two-three punch without precedent in motion-picture history. Scandal almost never diminishes curiosity about a love goddess, but Paramount (knowing that Dietrich's husband was already living openly with another woman in Berlin) thought it a good idea for Marlene to bring her child to America before she began her role in Sternberg's Shanghai Express. When the six-and-a-half-yearold Maria arrived, Marlene announced that she was four, and Paramount released a photograph of them that had been published in Berlin when Maria really was four.

No one will ever forget Dietrich's immortal line in the next film: "It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily." What Great Depression audiences may not have realized, but Sternberg surely did, was that Shanghai Lily's real name was Madeline (the German for which is Magdalen), and that Marlene's real name was Marie Magdalene, which she had shortened in childhood to Marlene. Here Sternberg perfected the streamlined, dangerous Dietrich, the exquisitely beautiful temptress halfhidden behind veils that give away nothing but her mocking smile. She is decked out by designer Travis Banton in costumes of no period that became as notorious as her dialogue: trunks of black egret feathers, black veils, black chiffon, black marabou. From then on, she was just Dietrich, and Paramount billed her that way.

Their next film, Blonde Venus, was a failure, and may very well have been Sternberg's vengeful message to Marlene—even though she wrote the screen story. It tells of a woman who leaves her husband to go off with a rich and powerful man (played by the young Cary Grant), kidnaps her child, and sinks to prostitution, which paves the way to her becoming the toast of Paris. In the end she discovers that the wages of sin are Everything She Has Ever Wanted. The buried theme of the film is beauty and the beast in one, which is made clear in the ultimate camp sequence, "Hot Voodoo"—even Shirley Temple did a parody—in which the blonde Venus emerges from a gorilla suit, only to appear later in a white version of top hat and tails.

After five pictures together, there was strain in the relationship, aggravated by an ongoing series of affairs Marlene had with Maurice Chevalier, Brian Aheme, and Rouben Mamoulian (who directed her next film, the tastefully dull Song of Songs), not to mention Garbo's inamorata, Mercedes de Acosta.

They reunited for The Scarlet Empress, their most dazzling film. Sternberg treated the story of Catherine the Great as a pure study of sex and power. Catherine as a child was played by Marlene's daughter, Maria, for whom Marlene had acting ambitions. Sternberg photographed most of the picture himself, including a five-minute-twenty-second wedding sequence with no dialogue. Dietrich was never more beautiful on-screen, never so iconic, with close-ups so extreme they frame only her eyes and nose behind veils so expertly photographed you can count the fibers in their weave. No camera was ever more in love with any woman than in this extraordinary sequence, and no woman ever yielded more serenely to its worship.

The Scarlet Empress seemed utterly irrelevant to audiences in 1934, who were flocking to It Happened One Night. The next year, Sternberg distilled his obsessive feelings in their last film together, The Devil Is a Woman—a title (dreamed up by Paramount) rejected by Sternberg, though it perfectly expressed the film and the relationship between director and star. The studio itself announced that the film was a disaster before it was ever released. Sternberg's goddess had become too distant and unattainable for Paramount's audience. Sternberg told the press he would make no more pictures with Marlene, and he let Marlene read it in the papers.

"I failed him," his puppet would say. It would have been truer to say that she had never been in love with him. She was fiercely loyal to him, but that could not compensate for the deeper, unreciprocated longings. He was never unaware of her other relationships, some of them conducted on his own sets, and her thinking him a genius did not ease the torments of nonpossession.

For the rest of her life she called him "the man I wanted to please most," but he was not kind to her in his memoirs. He admitted that all of their pictures were to some extent autobiographical, except Tor the most obvious one of all, the one he resisted acknowledging until the day he died: the story of an erudite professor destroyed by a heartless cabaret singer and vamp who is always "falling in love again," but never with him. He told the actor Sam Jaffe that he could do anything with Marlene but make her stop loving him. He may even have believed it. If he did, his leaving her was the closest he could come to saving himself from what was and always would be unrequited—except on-screen.

'Thre is a definite likeness to Greta Garbo," said Louella Parsons, "although Miss Dietrich is prettier'

She had pleased him—or not—for six years. Those years destroyed him, and made his reputation forever.

"Dietrich" had been created by Josef von Sternberg, but Marlene had a life of her own. Within a year, she would be the highest-salaried woman in the world, and over the next forty years she would make twenty-nine more films. No other star worked with so many great directors—Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Ernst Lubitsch, Orson Welles, Raoul Walsh, Mitchell Leisen, George Marshall, Fritz Lang, Tay Garnett, William Dieterle, Stanley Kramer, Jacques Feyder. And Maximilian Schell, a co-star from Judgment at Nuremberg, who managed in the early eighties to make a fulllength documentary about her, against her will and without photographing her, using only her voice on the sound track. The legend Sternberg created was so durable because it was, in fact, built on the real Marlene. The erotic sophistication, the androgyny, the cosmopolitan wit and intelligence, were not fantasies projected on a screen so much as they were essences of a woman too richly and unconventionally constituted to be focused even in the camera eye.

Away from the cameras, she was, if anything, more Marlene than films could say. She was a devoted mother and grandmother, and loved to be known as a hausfrau. Her loyalty as a friend and her nearly ruinous generosity became as much a part of the legend as her glamour and style. Her friendships had an intellectual basis as often as a romantic one, though she took her reputation as a seductress seriously and loved to shock people with her exploits from school days on, with both men and women. She had a standard answer when people asked whether she preferred men or women: "Women are better. But you can't live with a woman." That was why she could form famously close attachments to people as different as Ernest Hemingway, Edith Piaf, and Noel Coward. (When I asked her if she and Hemingway had been lovers, she answered straightforwardly, "He never asked me.") Her significant affairs amounted to what was called the Dietrich alumni association, which included Erich Maria Remarque, John Wayne, George Raft, John Gilbert, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Lieutenant General James Gavin, Michael Wilding, Michael Todd, Yul Brynner, Alberto Giacometti, and Jean Gabin. At the same time, she was emancipated enough to enjoy her own sex unabashedly, and while the beautiful Vera Zorina turned her down, that group of Hollywood women known as Marlene's sewing circle—Lily Damita, Ann Warner, and a number of well-known Hollywood figures who are still living—did not. Marlene's affairs could be casual to the point of being careless. Her brief fling with Fritz Lang ended when she reached across the pillow to pick up the phone and make a date with another man.

She was also capable of profound attachments, as with French actor Jean Gabin. The two lived together off and on between 1942 and 1946, in both Hollywood and Paris, and she often told people he was the great love of her life. When Gabin insisted on marriage, she demurred. Gabin was insanely jealous, demanding a kind of conventional relationship (including children) Marlene was not prepared, finally, to accept. Nor was she prepared to become Madame Gabin and stop being Marlene Dietrich.

Being Frau Sieber, however, had not slowed her since Maria's birth in 1924. Rudi was the perfect husband and the perfect excuse when other relationships threatened her independence. She got jobs for him and helped support him and his mistress as long as they lived. He died in 1976, shortly after the onstage fall that was widely assumed to have ended her concert career. "Marlene's career died with Rudi," one colleague said. "Everyone assumed her broken bones were the end, but not her! It wasn't her health that stopped her; it was Rudi." William Blezard, Dietrich's English musical conductor, who was with her when she fell, told me, "She was shattered when Rudi died. She always claimed she worked for Maria and the four grandchildren and would go on until she dropped, but after Rudi's death she said, 'I can't go on,' and I knew that was the end."

"Marlene swamped Maria with love," Douglas Fairbanks Jr. told me. "That poor child, who hardly knew who or where she was." Being Dietrich's daughter would have been a burden for any girl, let alone one who had been left behind when that ship sailed for America in 1930. She overate famously when she was a youngster, perhaps to avoid comparisons to her mother, whom she played as a child in The Scarlet Empress for the man she saw as her chief rival for her mother's attention if not affections, Josef von Sternberg.

When Maria came into her own as an actress in the days of live television on shows such as Studio One, she remained Dietrich's daughter. Though married and the mother of four sons, Maria Riva, as she was now called, could never truly compete with the radiance of Dietrich. She retired from acting in 1957 to raise her children. She and her family moved abroad, though they kept the town house on East Ninety-fifth Street in Manhattan that Marlene had bought for her.

In January 1992, two weeks after Marlene's ninetieth birthday, the world press was filled with reports of a book Maria had written about her mother. The front page of the London Sunday Times announced: DIETRICH'S DAUGHTER BETRAYS STAR'S SECRETS. Marlene Dietrich threatened to sue her own daughter to prevent Knopf from publishing the book before her death, which came four months later.

What Dietrich was to her daughter will soon be a matter of record. What she was to the world is already on the record. Her depth as a woman of courage and conviction and her freedom from the artifice of Hollywood were certified on the battlefronts of World War II. She became an American citizen and literally faced death for her convictions, braving rejection by her homeland, which has begun only now to comprehend the meaning of her sacrifice. She entertained on beaches, in forests, in bombed-out ruins, in hospitals, on the backs of jeeps, under direct enemy fire. Her work for the troops called on all those years in the theater before Josef von Sternberg ever laid eyes on her, and forecast what would be her last and greatest career.

In 1953, her status as the most glamorous woman in the world was so unquestioned that, when asked to perform for a cerebral-palsy benefit, she acted as ringmaster, in top hat and silk stockings, for the opening of Ringling Bros, and Barnum & Bailey Circus at Madison Square Garden. She so dazzlingly stole all three rings that she was invited to repeat her appearance in Las Vegas, and decided— as always—to give them a little more than they expected. At fifty-one, she walked onto the stage at the Sahara Hotel in a gown she had designed together with Jean Louis that was mostly sequins and rhinestones, strategically scattered over what was all Dietrich. Hedda Hopper led the standing ovation, and announced to the world, "Christmas came early to Las Vegas!" Overnight, Marlene became the highest-paid, most desirable nightclub act in the world. Soon only theaters could contain the entirely new legend she was building to add to those of the screen goddess and the warrior, and for that she found a second Svengali.

Burt Bacharach, at thirty, looked like a leading man, was well connected in show business (his father was a newspaper columnist), had composed a few unremarkable tunes, but was chiefly known as a savvy arranger who had worked for Mel Torme, Vic Damone, and Imogene Coca. He had the good luck to meet Marlene at the Beverly Hills Hotel when he was suffering from a cold, inspiring "Marlene Nightingale" to ransack her luggage for vitamin C and tender remedies.

He listened to Marlene's voice and set it in sound as Sternberg had set her face and body in light and shadow. He knew her voice had a narrow but serviceable one-and-a-half-octave range. It needed support, not cover, and a surround that would lend variety and color to what might otherwise drone to monotony. He haloed it with strings, boosted it with bass, encouraged her to let go with the surprising power hidden in her slender diaphragm. He added sparkle to her tone, lightened and loosened her rhythm, and forced her to swing.

He let her keep her standards, but added drive and shimmer and Broadway pizzazz. "My Name Is Naughty Lola" became more playful, "Lili Marlene" less portentous, "The Boys in the Back Room" flat-out, belt-it-to-the-balcony comedy. The show gained in variety and texture what it lost in familiarity. New songs helped update the image: "You're the Cream in My Coffee" was a teasing prank; "My Blue Heaven" became airborne romance; "One for My Baby" (straddling a chair and smoking a quarterto-three cigarette) was relaxed, boozybluesy; "Makin' Whoopee" winked and nudged; "I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face" was daring, with no gender change in the lyric. Bacharach let her croon, he let her belt, he let her purr and insinuate and suggest and toy. He even changed "Falling in Love Again." Her showy anthem got simple, with just a modest piano escort (his). After a full evening of acting songs, he made her throw it away. It became the intimate, scrawled signature at the bottom of a love letter, the one she had been writing with her lights, shadows, costumes, and songs for the whole evening.

By 1960 she was acknowledged to be the greatest solo turn in the world. She was ready to go home.

Berlin had been the site of her first triumph, but, though she was the most famous German woman of the century, many of her countrymen had never forgiven her for what they considered her betrayal in World War II.

Bacharach provided new arrangements for nearly a dozen German songs she had never sung in concert before. She knew from the forest of MARLENE, GO HOME! posters in front of the theater that this might be the toughest audience of her life. She displayed a dignity that rose above the fray without ever apologizing for the convictions that had driven her to risk her life and in the process save many others. Her performance was romantic, full of show-biz swank, but utterly unyielding. She asked no quarter and gave none until the end of the show. Then she pulled from her songbook a graceful closing number, "Ich hab' noch einen Koffer in Berlin" ("I Still Have a Suitcase in Berlin"), a nostalgic song that allowed a hint of homesickness.

Willy Brandt leapt to his feet. He was joined by the 1,400 others, cheering. By the end of the tour, in Munich, even standing room was sold out. She entered to what the press called "a hurricane of applause," and at the end did encores until there were no more, and then bowed that deep head-to-the-floor bow for an incredible sixty-two curtain calls.

Every important German review was a love letter, MAJESTY IN SWANSDOWN, one was headlined. "She is a legend. . .fascinating as a woman of the world, of the intelligence, of the spirit," another said. Munich's most important paper informed the skeptical, "Yes, it is true. [She is] ravishing, devastating—but the miracle of the image takes second place before the miracle of the performance—and that before the miracle of the personality. All together, this adds up to the miracle of Dietrich."

"Miracle" was not too strong a word. In Los Angeles a few years later, shortly after I finished my studies with Josef von Sternberg, I saw Dietrich happening, rehearsing on a stage with Bacharach and twenty-six musicians for four straight days. No detail was exempt from her attention, her correction. She drove the musicians and technicians as she drove herself, tirelessly, without complaint or drama. She exhausted every opportunity for improvement, every orchestra member on that stage, everything but her apparently inexhaustible self. Her sensitivity was so great that she could feel if a spotlight two balconies up was too hot or too cool. She could tell if a microphone had been moved a quarter of an inch while she was at lunch.

At the end of thirty-two grueling hours, Bacharach thanked his musicians and announced that rehearsals were over. Dietrich stood facing the empty theater (where I crouched unseen in the top row of the uppermost balcony) and gave her pre-opening speech to the orchestra. "All right," she said. "All right. Burt says rehearsals are over, it's time to stop, time to go, and Burt knows. He knows your union rules and your own rules; he knows your freeways and your lawn sprinklers and your swimming pools and your televisions, your standards and your aspirations. And so you must go home to your little wives in your little houses in the hills or the San Fernando Valley. I am prepared and willing to stay here all night. All night and all tomorrow too. To get it right. To justify this thing we are doing, this act of theater. But no. Your pools and martinis and television sets and wives are waiting, so never mind. Never mind that we open tomorrow night before the most cynical audience in the world. And we are not ready for them. But go. Go home and relax. And as you do, think that we open tomorrow night, and tomorrow night will be"—her voice hushed to near inaudibility—"a disaster."

Mike Nichols said Marlene was the only woman who never looked in a mirror on an evening out: "She didn't have to; she got it right in advance."

It was, of course, one of the greatest triumphs Los Angeles had ever witnessed.

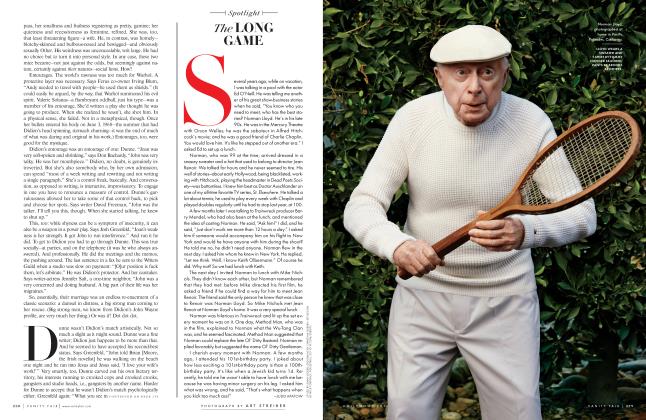

Creating triumphs was by now her stock-in-trade, offstage as well as on. Mike Nichols observed that Marlene was the only woman he'd ever spent an evening with who never looked in a mirror once: ''She didn't have to; she got it right in advance." Concealing the enormous cost it took to get it right was part of her professionalism. She was both admired and notorious for her self-punishing ordeals in having what looked like simple street clothes made. She drove seamstresses and couturiers to distraction. For the public Dietrich, her discipline and demands took on the aura of mania. When she and Jean Louis created her famous concert dresses, she thought nothing of standing before a mirror nine hours without a break as costumes were literally built on her body, sequin by sequin. ''She hated symmetry," Jean Louis told me, ''and a sequin here might make a symmetry with a rhinestone there, and we'd have to redo the whole thing until it was perfect."

For her Tokyo concerts, she checked into the Imperial Hotel and delivered her order to room service: twelve wastepaper baskets, thirty-seven luggage stands, an ironing board, an electric typewriter, twenty-four telephone pads and pencils, a hot plate, a saucepan, double-strength light-bulb replacements, blackout curtains, floodlights for makeup and dressing. Hotel staff were allowed in her rooms only in her presence, and never in the room where her costumes or foundation garments were laid out. She made herself up at the hotel. She had used tape "lifts" under her wigs since the early forties, and as she entered her sixties, she learned to braid her hair and attach the braids to tiny surgical needles, which she then pulled tight and imbedded in her scalp. She daubed the pierced skin with over-thecounter antibiotic ointment to prevent infection from her stage wigs. Only then would she apply the stage makeup that created the illusion of agelessness. To help the process along, in 1961 she underwent "fresh cell" therapy in Switzerland. Her care for her body went all the way back to her apprentice days in Berlin, when she took boxing lessons to keep in shape. She was capable of starving herself to stay slim and satisfying hunger by selfinduced vomiting in order to eat her cake and not have it, too.

In 1965, at the Edinburgh Festival, she learned that the man on whom she depended for amitie amoureuse, as she liked to call it while stroking his hair for photographers, was leaving her.

Bacharach had always wanted to be a composer. She had known that, but in their whirl around the globe she had discounted how much he wanted a settled life with marriage and children. He had found the woman with whom to settle, film actress Angie Dickinson.

Marlene had known the day would come, which did not lessen the shock or rage when it did. Dickinson had gone to London to meet Bacharach and travel on to Edinburgh. A healthy sense of dread sent her to Clive Donner, director of What's New, Pussycat?, for which Bacharach had provided a hit song. She asked him to come along for company while Bacharach conducted, "but really for moral support," intuited Donner.

"Marlene went into a fury," he told me, "more in sorrow than in anger, perhaps, but it looked and sounded a good deal like anger. ' ' Another observer shuddered and closed his eyes, remembering what he said "was not a pretty sight." Donner was struck by Dietrich's voicing "a certain helplessness without Bacharach that was completely contradicted by the imperiousness of her rage. She told him he was ruining his career. Not by leaving her to compose and conduct for films, but by marrying someone who wasn't a star. It was as if she were thinking in the third person like an adviser or agent, and he had chosen a nobody over Marlene Dietrich! I wondered what her reaction would have been if he had said, 'Marlene, I'm leaving you to marry Garbo.' She might not have been so outraged."

Nothing could stay the performance, however. Donner remembered they "got through the evening somehow. We left the theater and piled into a limousine at the stage door, where hundreds of fans were waiting. Dietrich had a clutch of signed postcards with her photograph in the famous gown and slipped them one by one through the partially open window of the car. She kept telling the driver, 'Slower, slower,' and then, just as we reached the comer where the car had to turn, she shouted, 'Fast/' and as the car turned the comer, she released a great arc of hundreds of these postcards. They fluttered through the air like ticker tape at a parade. The fans dove after them as Dietrich sat back and smiled. It was a brilliant display of theater. Angie Dickinson couldn't do that."

She had gone on without Sternberg. She went on without Bacharach—calling on his deep and genuine loyalty to her when occasion demanded, such as her triumphant 1967 and 1968 Broadway appearances, when she was billed as "Queen of the World."

She was endlessly self-contemporizing. She could sing Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan as movingly and persuasively as she could Cole Porter and Harold Arlen. She had no competition, and knew it, and loved being Marlene Dietrich. She liked to say she knew her limitations, but that was never the same as accepting them. She made what she did look effortless, because that's how great artists do it.

On May 6, she fell asleep forever in that apartment on the Avenue Montaigne. It was the day before the opening of the 1992 Cannes International Film Festival, which was dedicated this year to Dietrich—image, legend, woman. Dietrich's Dietrich.

Kiosks all over Paris bore ads for the festival, with her image as Shanghai Lily. Along the Avenue Montaigne itself, that beautiful face shone from poster after poster over the milling crowds of photographers, fans, and the merely curious waiting for the quite inconceivable news that the Blue Angel had folded her wings.

Her exit on the day before the Cannes festival's opening must have pleased love's old warrior. It made it impossible for filmdom's gaudiest self-celebration to begin without celebrating her.

Talk about timing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now