Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

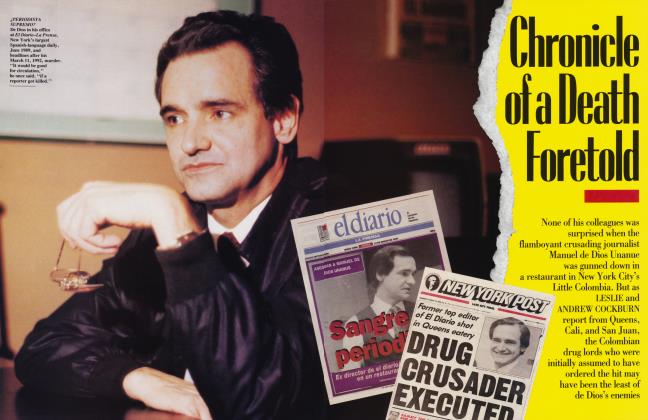

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIt looked as if the worst moment of Rodney King's life might bring his best chance to escape the downward spiral of poverty and despair. Instead, while politicians, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and even family members race to capitalize on "the Rodney King supersuit," King himself languishes, tormented, in a Ventura County safe house. PETER J. BOYER reports on the exploitation of America's most famous victim

July 1992 Peter J. BoyerIt looked as if the worst moment of Rodney King's life might bring his best chance to escape the downward spiral of poverty and despair. Instead, while politicians, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and even family members race to capitalize on "the Rodney King supersuit," King himself languishes, tormented, in a Ventura County safe house. PETER J. BOYER reports on the exploitation of America's most famous victim

July 1992 Peter J. BoyerIt was a good day, a full and prosperous day, in the Rodney King trade. Across Los Angeles, the politicians, the preachers, the journalists, the Hollywood compassion-and-healing crowd, the lawyers, the agitators, the T-shirt peddlers, the con artists and charlatans, all rose early and stayed late. They worked the charred and empty comers of the town, and they worked the gleaming, moneyed, undisturbed corners too, seeking photo ops, easy money, production deals, a new angle, an audience, a sanctimony fix, and finding an abundant yield.

Angela King, Rodney's aunt, was up at four that morning, ten days after the explosive not-guilty verdict for the cops who'd beaten her dead brother's son. A local politician sent a car to Angela's home, behind a storefront in the starkly delineated black section of Pasadena, to chauffeur her through a busy schedule. She was in a TV studio at five A.M., then moved on to a Baptist church in South-Central, where she met George and Barbara Bush, and from there went to a drug rehab center for young women, where she gave a little talk—Aunt Angela is wanted for public appearances now.

The president and his wife had gotten up early, too, leaving the Bonaventure Hotel downtown for a tour of the devastation, along the way passing hawkers of bootleg Rodney King T-shirts, and swindlers working cons in the first flush of the rebuilding effort. Bush showed that his speechwriters, at least, had heart—"To truly help, we must understand the agony of the depressed,'' he told the South-Central church crowd, and "You can't solve the problem if you don't feel its heartbeat." For those law-and-order voters, his thirty-one-car motorcade stopped at an L.A.P.D. station, where he sympathized with the cops: "It's not easy times." Bush's newly rediscovered urban-policy man, Jack Kemp, was invited along for the ride.

Across town, in Studio City, Pat Buchanan told a prayer breakfast that the rioters were not motivated by deprivation or a sense of injustice but were the products of misguided liberal policy, including public education. "They came out of schools where God, the Ten Commandments, and moral instruction have been expelled," Buchanan said, "and sex education, 'values clarification,' and condoms have been put in." Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, was out in Orange County talking about the rioting with high-school students.

Over in his law office at the edge of Beverly Hills, Steven Lerman told a Spanish television network that he was much too busy to fly to Madrid for an appearance. Lerman, a longtime "P.I." (personal injury) specialist, was preparing Rodney King's civil-rights suit against the city of Los Angeles, seeking $56 million—$1 million for each blow—or $83 million, or maybe $94 million, depending on which estimate you took on which day. A receptionist told at least one prospective client that Lerman's office wasn't taking any new cases, because it was fully occupied with "the Rodney King supersuit."

In the San Fernando Valley, attorney James F. Jordan awaited a callback from a production company that had expressed interest in buying the movie rights to his client's story—his client being the thirty-two-year-old plumbing-company manager who had taped the King beating to try out his new Sony Handycam. "Not even the Zapruder film is as important as this," Jordan said by way of explaining why he had also asked for roughly $9 million from the television stations across the country that have already used the famous footage. Jordan said that his client deserves his share of the financial activity the tape has created. "You know, this is America. If you've got a gold thimble in a haystack and you find it, God bless you if you can take it and make a dollar with it. Because that's what this country is all about."

Down the 405 Freeway in Orange County, attorney James Banks was also awaiting a call that he hoped would open a movie negotiation. Banks represents a fledgling entertainment company—of which he is also a vice president—that quietly scored a coup when, two months after the beating, it bought the rights to Rodney King's name—"coffee mugs, T-shirts, you name it." Banks said his company is at work on a movie, books, and a mini-series, and is weighing its merchandising options. "Big," he said with a bit of a snort. "I don't know if that is a big enough word for the Rodney King thing."

The company, virtually unknown in Hollywood, a town that loves to know everything, is called Triple-7—as in hitting the jackpot.

By day's end, a glittery crowd had assembled in Century City for a solidarity march. Carrying placards calling for "justice," they were led by Anjelica Huston and her soon-to-be husband, Bob Graham, to Beverly Hills, where Huston, wearing cowboy boots and a denim jacket, gave a passionate speech, calling for the healing of the city's and society's wounds. Several marchers thought that Huston showed promise as a celebrity advocate, possibly another Vanessa Redgrave, or at least another Jane Fonda.

King has told people he's miserable in his cloistered life."He's just kind of jittery."

And Rodney King? He was everywhere that day—on the lips of the pols, on the backs of the T-shirts—and he was nowhere. He was not in Los Angeles, nor had he been there much lately. He was shut away in a safe house in (of all places) Ventura County, wrapped in the arms of psychopharmaceuticals, and under the twenty-four-hour watch of a private-security team led by (of all people) a former L.A.P.D. cop.

The guards work in shifts so that King is never alone, not even for an evening stroll around the block with his wife, Crystal. When he goes anywhere, even to the barbershop, he is driven by a member of the team—but then, there's really no place to go in the county where a mostly white jury acquitted the cops who beat him. And so, says Aunt Angela, "he watches TV."

This secret life has been constructed for King by Steven Lerman. Tormented by recurring nightmares of the beating, King is convinced, with the help of his attorney, that he'll come to harm—or worse—if he ventures outside the cocoon. Inside, with a cellular phone and an endless stream of rented videos Lerman has provided, Rodney King is living a strange, and completely American, paradox. The most hellish moment of his life has presented him, through no initiative of his own, with greater prospects than he'd ever imagined possible, and from which he is almost completely excluded.

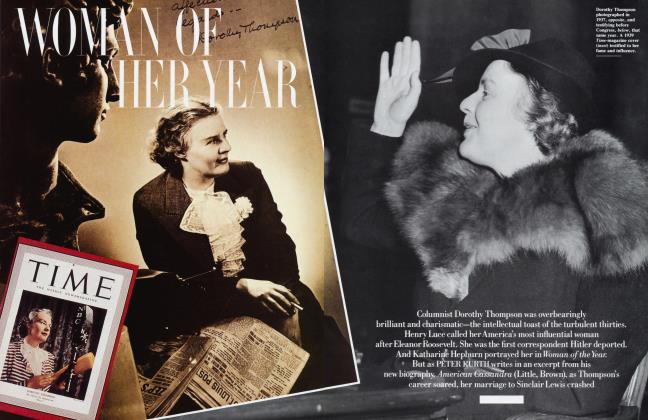

His words make the cover of Time magazine, his name is attached to the rising—or crashing—careers of the sort of people he'd never be in the same room with, he gets private messages of sympathy from the president of the United States. Lawyers, agents, filmmakers have hustled to get a piece of him. The onslaught has provoked his family to bickering over merchandising and story rights. And now he couldn't help them if he wanted to, because someone else owns his name.

Rodney King has become a mythic symbol of denied justice, with much commerce and national debate and a riot being conducted in his name, but he can't sleep at night, or go home to the 'hood for some beers and a barbecue.

To say that Lerman has put a tight rein on Rodney King does not begin to describe the control he exerts over his famous client. "Svengali" is a word that arises more than once. Lerman hired Tom Owens, the former L.A.P.D. officer, to supervise a security force which ensures that his "operation" is not penetrated, as well as a psychiatrist to monitor King's psyche and administer antidepressants and other medications.

"I just want to be a normal family again, and peaceful, like we used to do," says Aunt Angela. "Where does he go in Ventura? Nowhere. Every time I call, he's at home. ... They've increased his medicine because of this incident right now [the acquittal and the riots]. He was to where he was Rodney again—lively and just outgoing.... Now he's back on that medicine. And way out there. You gotta go across three freeways to get to him."

"The way Lerman's got Rodney," says one colleague of Lerman's, "is sort of like when Patty Hearst joined the Symbionese Liberation Army."

Rodney King spent more than a year sprawled on that L.A. street, hunched against the blows of the police batons, as that videotape replayed itself on an endless loop in American living rooms, searing that image deep into the American eye. In a way, the eighty-one-second tape erased King's life before and after the beating. It was all we knew, and, it seemed, all we needed to know: he was the national definition of victim. Then came the acquittal and the rioting and King's halting, affecting plea for peace. The image expanded: he became an emblematic figure. Time longed for national leaders who could be so eloquent; a New York columnist equated him with Rosa Parks, the brave mother of the modem civil-rights movement, who refused to sit in the back of an Alabama bus. Others have placed him on a par with Martin Luther King Jr.

But Rodney King is not Rosa Parks, he is not Martin Luther King Jr., and, for that matter, he is not even Rodney King. He's always been known as "Glen," his middle name, and the fact that he became "Rodney" after the event summarizes the transformation imposed upon him by that videotape. He had a life before those eighty-one seconds—a life at least as revealing of the nature of our separating society as the hollow debate over which failed policies should be blamed for "the rage of the urban underclass," as the handwringers like to call the burning down of cities. It is a life in some ways more difficult to confront than the brutality on that tape.

Rodney Glen King was born in Sacramento in 1965, the year that Los Angeles was last inflamed, to a family that fell somewhere in the middle of the black American spectrum—not quite middle-class, but a toehold above the hopeless poor. As Aunt Angela tells the family history, his father, Ronald King, was from Kentucky, the son of an air-force sergeant who was often absent and a mother who left Ronald and Angela when they were toddlers. When she eventually came back for them, she'd had two other children by another man, and Ronald and Angela were each assigned one of their infant sisters to help raise.

They landed in Sacramento, where Ronald went to high school. Then he married Angela's best friend, Odessa, and the three of them moved south to Pasadena. Ronald was a sometime construction worker, but there weren't many jobs, and he drank, and so he mostly settled for daywork as a maintenance man. Odessa and he had a baby, Ronald junior, and then Rodney Glen, and kept going until they had five children.

It was a rough life. "They didn't have enough food," says Angela. "I was a nurse's aide, and then I had this little lady—I was taking care of her kids, like a nanny—over in Glendale. And Ronnie, he didn't want me to know, but I'd go over there to visit, and they didn't have no food, and their kids were walking around with T-shirts for diapers." Angela moved in with her brother and sister-in-law, putting her rent money into the household, but the life-style remained borderline at best. As Glen and his brothers and sister grew, their father drank more heavily; their mother sought solace in the Jehovah's Witnesses church.

There was love in the family, but trouble too, enough to smother hope. Ronald King sank deeper into alcoholism, and died at forty-two. Angela says one of their sisters moved in with a man who beat her, requiring Glen's regular intervention. Another sister, Juanita, simply vanished one day and hasn't been heard from since; Angela thinks she may have died with Jim Jones at Jonestown. Glen's younger brother Juan got caught up in the beating of a policeman and spent more than a year behind bars. "He never even went to court on it—he went to jail," says Angela. "I feel terrible. We couldn't afford a lawyer."

By the time Glen got to high school, he was a big, handsome boy, six feet three inches and nearly two hundred pounds, but his future would not be made in school. He was only marginally literate, and was held back a year and placed in special-education classes. He dropped out in 1984, just months before graduation. His prospects for advancing beyond the life his father had known were dim, and grew dimmer when he and his girlfriend, Dennetta, had a baby. Now there was pressure to bring in money, but most of the jobs open to him were low-paying and unsteady. He and Dennetta separated, he had a second child with another woman, and the pressures grew.

He worked when he could, and he hung out, drinking "eightballs"—forty-ounce bottles of Olde English 800, the beverage of choice in his neighborhood. He avoided trouble, or serious trouble, anyway—he was picked up on a vice bust in Pasadena but was later released. Then he got married to a neighborhood girl named Crystal Waters, who had two children of her own. He was not exactly prepared to head up a household, and shortly thereafter he slipped beyond the edge.

One day in late 1989, needing money, King stuffed a two-foot-long tire iron under his jacket and walked into the 99 Market in Monterey Park to get it. He bought a pack of gum, then pulled out the tire iron and ordered the Korean store owner, Tae Suck Baik, to "open the cash register."

Baik complied, and King stuffed the cash into his pockets. Then, looking in the cash register, he reached for some checks, and the grocer struck him. King dropped the tire iron and tried to flee. When Baik pursued him, he picked up a metal rod and struck the grocer with it before hopping into his white Hyundai and driving off with a take of about $200.

King was quickly caught, pleaded guilty to second-degree robbery, and was sentenced to a two-year term at the California Correctional Center in Susanville. After several months in jail, he wrote a letter to the court asking for early release:

"I have all good time work time. I have seriously been thinking about what happen and I think if it is possible that you can give me another chance, your honor. I have a good job and I have two fine kid who wish me home. Have so much at stake to lose if I don't get that chance. My job and family awaits me. So please reconsider your judgement, your honor. The sky my witness and God knows."

The judge did not release King, but he was paroled in December 1990, after serving one year. He went home, and, less employable than ever, was unable to find work in construction. He took a part-time job as a laborer at Dodger Stadium and spent a lot of time hanging out with his neighborhood friends, such as Bryant Allen, known as Pooh. They had been friends since they were teenagers, and in a way they were even related: Pooh's sister had had a child by King's older brother, Ronald. And they were together on that night, March 2, when everything changed.

They had just been hanging out with a friend of Pooh's, Freddie Helms ("Freddie G."), nothing much to do, when King suggested they take a ride in his car. Pooh didn't know where they were going, but he later recollected that Glen had said something about driving to Hansen Dam, up the 210 Freeway, where they could hang out and maybe meet some girls. It was a bit late for that, past midnight, but Pooh and Freddie G. were game, and off they went. They'd been drinking that night, and had an eightball in the car with them when King saw the flashing lights of a California Highway Patrol car in his rearview mirror.

King panicked and tried to get away, leading the CHiP car, driven by a husband-and-wife team, on a chase at speeds originally reported to have reached 115 m.p.h. but later revised downward. King got off the freeway in a community called Lake View Terrace, where he finally pulled over. "When police pull you over, man. . .you always kind of, your heart start jumping a little bit, you know, boom, boom," King later told investigators from the district attorney's office. He said he thought, "[I] hope they don't beat my ass with anything. That thought always go through everybody's mind."

Summoned by an A.P.B. at 12:47 A.M., the L.A.P.D. officers had arrived on the scene. They told the Highway Patrol team that they'd handle things from there.

George Holliday was awakened from a sound sleep by the loud thwap-thwap-thwap-thwap of a police helicopter churning right outside his apartment window. He got up, put on his pants, and went to the balcony of his second-floor apartment to see what the commotion was about. When he saw all the cops, and the scene bathed in light, he immediately realized he had the perfect occasion to try out his brand-new Sony Handycam. He started taping.

When it was over, Holliday put his camera away and went back to bed, not fully realizing what he had recorded. It wasn't until late the next afternoon, a Sunday, that he thought to view the tape he'd taken the night before. Stunned by what he saw, he called the local L.A.P.D. station and asked what had gone down. They wouldn't say. He then called CNN, but no one answered at the L. A. bureau. Finally, he called KTLA, Channel 5, where he was told they'd take a look at the tape. It was broadcast on the ten o'clock news that night.

By the next morning, outrage was felt throughout the city, and among those most determined to obtain justice for the motorist in the video were the lawyers of Los Angeles. It was the case of a lifetime.

"It was just a circus. Everybody was trying to get a piece of Rodney."

It seemed likely to go to one of a group known informally as "the brutality bar"—lawyers who, because of the L.A.P.D.'s disproportionately large share of brutality claims, have made civil-rights-abuse cases the focus of their practices. Known as "the True Believers" by the city attorneys whose task it is to defend cops, these lawyers have their own referral service, Police Watch, which is well known in communities with frequent L.A.P.D. abuse complaints.

"All of a sudden, here's this case. . .and it turns out where [King] was staying was right down the hill from where I live," says Pasadena attorney John Burton, a Police Watch co-chairperson. ''I was flipping out. I was saying, 'Oh, please, I've got to get this case!' "

But the rush to represent King was by no means limited to members of the brutality bar. The jail where he was being held for resisting arrest suddenly looked like an American Bar Association convention. ''It was just a circus," says Robert Rentzer, a criminal lawyer in Los Angeles. ''Everybody was trying to get a piece of Rodney."

But they were too late. Someone had gotten there ahead of them.

The attorney who'd already landed King's signature on a retainer agreement was not a member of the brutality bar, nor was he known to have ever tried a civil-rights case. The legal community was stunned when it discovered that Steven Lerman, a P.I. specialist, had signed the client.

"We in the police-misconduct bar in Los Angeles just consider [King's] hooking up with Lerman to be one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century," said one disappointed lawyer, "sort of up there with the Moscow trials and the sinking of the Titanic."

How did Lerman get the case? He refuses to say, citing attorney-client privilege. Angela King, who was privy to the decisions being made in the early hours of her nephew's trouble, says that Lerman was suggested to the family by Warren Wilson, a reporter at Channel 5—the station that had the Holliday videotape first.

Wilson, one of the best-known black reporters in town, has been a fixture on local television for years. He also has a law degree, although he has not yet passed the California bar exam. Wilson says that he does know Lerman, and that Lerman's name was one of several he mentioned to the family while he was covering the story.

The question of propriety seems obvious, but attorney Stephen Yagman, a police-abuse specialist who practices in Los Angeles and New York, says that reporters routinely steer potential clients to lawyers in L.A. "A lot of lawyers in this community, including me, have tie-ins with people in the media, people I'm buddies with. And if people say to them, 'Do you know a lawyer?' the reputable reporters will say, 'I can't recommend a specific person, but here are the names of three or four people who do this.' The less reputable ones will say, 'This guy here is the best guy there is.' I've gotten maybe 30 percent of the cases we have from people I know in the media."

However Lerman got King, once he had him he held tight. Rentzer, who was hired by the family to handle Rodney's criminal charges, says he had an agreement that he would have a hand in the development of King's claim against the city. When the criminal charges were dropped, Rentzer says, "Lerman manipulated me out of the case." "I would deny that I chased him out," Lerman says.

But the elbowing to get close to Rodney was not limited to lawyers. Rodney's new fame caused a bitter rift within his family over such suddenly relevant matters as movie rights and merchandising—not to mention who would get to go on Donahue.

Rodney's mother, Odessa, is a deeply religious woman whose faith prevents her from getting involved in matters of this world—a category in which her son's legal case securely fits. She stayed in the background, and insisted that her four other children, also Witnesses, do so, too. That left a void, which Aunt Angela and Kandyce Barnes, the aunt of Rodney's wife, Crystal, struggled to fill.

Kandyce had two advantages—she was well spoken and, through Crystal, she had Rodney's ear. Angela says there have long been class tensions between the two families. "They had some money, they had a home, and [to them] we were just slums—you know, lower-class people. ... They just pushed their way on in there."

A month after the beating, Kandyce and Steven Lerman went to New York to appear on the Phil Donahue show, and, speaking for the family, she told the national television audience that Rodney was "very paranoid." She said that he awoke in the middle of the night, screaming, "Don't beat me! Please leave me alone!"

Aunt Angela went ballistic over the Donahue show: "These little aunts and the in-laws, they get on there like they've been knowing Glen. They don't know him. No, no. No way... . These people are snakes." And her antipathy was not eased by the events that occurred next.

Kandyce, saying that she had experience in negotiations, persuaded Rodney to let her guide him as he chose among offers to buy the rights to his story. The company she selected was an unknown newcomer, Triple-7 Entertainment.

James Banks, the Triple-7 vice president and lawyer, describes it as "a motion-picture producing company, as well as a television production company and a book company." Actually, that is a hopeful assessment. So far, the company has produced only a how-to-make-your-child-a-star video, due out this summer. Banks says that Triple-7 "consists of people who have been in the entertainment business for many, many years," but "because of their involvement in other projects they do not want to be known at this time."

The company was officially formed on May 1, 1991, two weeks before it signed Rodney King. "As you can imagine, in the beginning, the bidding was horrible," Banks says. "Everybody and his little brother was coming out of the woodwork to buy these rights, from one coast to the other."

And how was Triple-7 chosen? Kandyce says that she merely acted as a "go-between" for King, sorting out and presenting him with the various offers, and that Triple-7 emerged as the best choice. Banks, however, says that Kandyce approached Triple-7 through a mutual friend, one of the silent partners. "It boiled down to the confidence in the friendship, in the relationship, that did it for [King], no doubt about it in my mind," Banks says. He adds that Kandyce may get a co-producer's credit on the movie and the mini-series Triple-7 plans to make. ("I'm flattered to hear that," says Kandyce.)

Apparently, King had no advice on the negotiation except for that of Kandyce. Steven Lerman says he did not participate. And Aunt Angela knew nothing of the deal until after Rodney had signed it. "He was not even well yet—that's what made me sick."

But, Banks notes, "the document involved is as good as any Philadelphia lawyer could put together. It's a bona fide contract." Banks declined to say how much Rodney was paid for signing the contract. Angela says she heard it was $20,000.

And what did Triple-7 get for its money? "Rights to Rodney King's story," says Banks, "lock, stock, and barrel."

For Banks, an entertainment lawyer, and his partners, the King signing represented a magic entry into the big leagues, and to say he is enthused does an injustice to his enthusiasm. "I mean, what else can you compare this to? I don't think there's anything else. Not since those boys, [the Founding Fathers] signed that other document [the Constitution].

"Without sounding theatrical, it has such an impact that, to do the story, it ultimately has to be a feature film for the rest of the world. Domestically, probably a mini-series. A three-night mini-series on him." That is not all. There will be a book. "There are really two books, I should say. There's the making of the story, and the story. Because the making is almost as interesting as the story."

Banks has an idea in mind for a T-shirt: "I think Mr. King's statement. .. 'Can't we work together?' Glen's statement was a beautiful statement. And I think that, with his picture, would be very apropos." Meanwhile, Banks is busy writing "cease and desist" letters to bootleggers using Rodney King's face or name without a license, and he has an investigator tracking the pirates down.

All of which leaves Aunt Angela—and, she says, the rest of the King family—out in the cold. "We're looking at millions and millions of dollars," she says. "And everyone's trying to find out who's doing what. Everyone except for his own immediate family. And he can't see this."

With books and movie projects and the multimillion-dollar civil suit all in the works, King became a valuable commodity. But his partners soon realized that he was also a risky investment. In May 1991, with the ink still not dry on his Triple-7 deal, King drove to Hollywood, where, in a dark alleyway, he engaged the services of a transvestite hooker. As luck would have it, two undercover L.A.P.D. vice cops were watching this particular prostitute, and they moved in for the pinch. King tore out of the alley, nearly running over one of the cops. He then stopped a patrol car, told the cops about the incident, and was arrested for assaulting a police officer with a deadly weapon.

Lerman maintains that the assault charge was a setup by the L.A.P.D., which was bent on discrediting King. For its part, the state attorney general's office decided against filing charges. "We felt that it was a defensible case, considering that they were undercover and there wasn't a reasonable conclusion that [King] knew they were police officers," says Deputy Attorney General Peggy S. Ruffra, who handled the case. "There was some reasonable doubt as to whether he was trying to run over the person or just get the hell out of the alley."

Still, nobody denies that Rodney King was in that alley with that hooker—"I'm his lawyer, not his conscience," Lerman says. And soliciting hookers in dark alleys was not the ideal way for a man with a multimillion-dollar civil suit pending against the local police to be spending his leisure hours. King's minders realized it was imperative to keep him from getting into any more awkward circumstances. But Lerman prefers a different emphasis. "Rodney King doesn't need a keeper," he says. "Rodney King needed protection from those that would do him harm. And the fact that he was set up [in Hollywood] underscored his vulnerability."

King has told people he's miserable in his cloistered life. "He's just kind of jittery," Angela said after a recent visit to Ventura County. "He asked me to come out there; he wanted me to sit and talk with him awhile. He gets lonesome, and I know how it is—you know, your family not around."

"Rodney King is a victim," Lerman says, "and my intention is that Rodney King never become political fodder."

But Lerman has convinced King that he needs his lawyer's shroud to survive. "He's mindful, because I've told him that there are people out there that know their place in history could be assured if they took a shot at him," Lerman says. "I have to take Rodney King and...say, This is what's good for him. Not good for him because he likes it, or he agrees with this or that. I enjoy a dialogue with him that's unique."

Lerman says that he has made King "part of my life," and that he has spent "hundreds of thousands" of dollars of his own money on the case so far. Lerman's colleagues and competitors are in awe of the effort. "I mean, he's basically put King on a salary," says one. "He seems like he doesn't have any other cases. It's quite remarkable."

The tight rein has clearly accomplished several crucial goals. If King's life is really in danger, it has kept him safe so far. And it has kept away other lawyers. "There were many attorneys chasing him down, trying to solicit the case, trying to dissuade him from continuing to have Lerman represent him," says Rentzer. Lerman has also successfully kept at bay leaders of the black community who have sought to give King a more public role in confronting racism. "Rodney King is a victim," Lerman says, "and my intention is that Rodney King never become political fodder, never become ammunition for somebody's agenda."

It's safe to guess that Rodney King was a reluctant volunteer when he made his famous plea for peace outside Steven Lerman's office two days after the cops' acquittal. "He was terrified," says James Banks. Reporters and TV crews, two hundred strong, had assembled. An L.A.P.D. helicopter hovered overhead. Los Angeles and the nation were waiting to hear from the man in whose name the city was being burned. Dozens of people had already died, and although the National Guard and Mayor Bradley's dusk-to-dawn curfew had quieted the town, the wrong signal from Rodney King could easily ignite another explosion. In fact, someone from Bradley's office called Lerman just before King's appearance for assurances that King would do nothing to heighten tensions.

Wearing a blue jacket, blue slacks, and a blue shirt, King walked into the sunshine on Wilshire Boulevard and said:

"People, I just want to say. . .can we all get along? Can we get along? Can we stop making it horrible for the old people and the kids? . . . We've got enough smog here in Los Angeles, let alone to deal with the setting of these fires and things. It's just not right. It's not right, and it's not going to change anything.

"We'll get our justice. They've won the battle, but they haven't won the war. We will have our day in court, and that's all we want. . . . I'm neutral. I love everybody. I love people of color. . . . I'm not like they're. . .making me out to be.

"We've got to, quit. We've got to quit. . . . I can understand the first upset for the first two hours after the verdict, but to go on, to keep going on like this, and to see this security guard shot on the ground, it's just not right. It's just not right, because those people will never go home to their families again. And I mean, please, we can get along here. We can all get along. We've just got to, just got to. We're all stuck here for a while. . . . Let's try to work it out. . . . Let's try to work it out."

And then, taking no questions, he was escorted back inside. It was a remarkable performance, and none were more pleased with it than Steven Lerman and James Banks, who had advised King as to the tone, and even the phrasing, of his words.

"I told him that there are certain things that people will probably want to hear him say," notes Lerman, "but that what he said would ultimately be his decision."

"The telephone lines were really buzzing," says Banks. "Glen and I talked just like two guys sitting around just shooting the bull, as to what we wanted to come out of this. We talked about Dr. Martin Luther King. And I said, 'Glen, you know, I was there when he made that speech, "I have a dream." ' I wasn't physically there, but I was around then. And I never dreamed that one day I would be associated with a speech that is a thousand times more important, in all due respect to Dr. King. ...

"And we talked about the phrase—and I'm so glad that he said it—I said, you know, 'Glen, this is just a battle we lost, but we're gonna win the war.' And I was very pleased that he talked about that. It had a strong resonance. And the one that was all his own was when he said, 'Can't we work it out? Can't we work together on this?' That was right from the heart. That tore everybody apart."

While King's plea seemed to guarantee the peace, it brought a near-universal reaction: Why didn't this man testify at the trial?

"He would have been a fantastic witness," Lerman says, "a fantastic witness." King himself later criticized the decision not to call him to the witness stand.

Deputy District Attorney Terry L. White, who prosecuted the four cops, gets edgy when he hears statements like that. The case had been a political nightmare for the D.A.'s office—which ordinarily works with the police department, not against it—and it was White, still only in his thirties and far from the department's most experienced assistant D.A., whose career might be on the line.

White had to have heard the gossip that District Attorney Ira Reiner, a veteran L.A. politician, chose him, a black attorney, as an insurance policy. If they lost the case—unlikely as it seemed, with that videotape as evidence—"the black community would have to trash one of its own to get to Reiner," as one L.A. lawyer puts it.

Almost from the beginning, the question of whether to call Rodney King as a witness was a central dilemma for White and Reiner, and the subject of intense debate for weeks. All but Lerman agree that, on some obvious levels, King was a vulnerable witness. Not only was he an ex-con—and if he'd taken the stand, the defense would have tried to explore his conviction for a violent crime—but he'd also been drunk the night of the beating and had led police on a high-speed chase, running lights and driving erratically along the way.

Moreover, King had rendered his testimony "impeachable" by giving inconsistent statements on several key points. He made early statements that he hadn't been speeding and that he'd pulled over immediately—statements contradicted by one of the passengers in his car, Pooh Allen.

In his early interviews after the incident, King said he couldn't identify the officers who'd beaten him, but later he identified all four defendants in the criminal case. "You know, my memory is coming back," King explained to the D.A.'s investigators. "I've been able to, you know, think at times and my brain, you know, it would come back different parts, different little parts, little bits."

King's most glaring contradiction was on the matter of whether the officers uttered racial epithets while they were beating him. At his first press conference, on leaving jail, King said that there had been no racist remarks, a statement he repeated to the police investigators. Lerman said the same thing, as did Rentzer.

But as Lerman shaped his civil suit around civil-rights violations, race became a central point. King now told the D.A.'s investigators that the cops had stood over him, taunting, "Whatsup, how're you feeling now, nigger? Whatsup, nigger? Nigger, whatsup, nigger, killer? Killer, whatsup, killer? Whatsup?" He also said that when he got up and tried to run—a moment, according to the defense, that showed he was belligerently resisting arrest—it was because an officer had said, " 'I'm gonna kill you, nigger, run!'. . . And when I heard that, when I heard that, that's when I was gonna break for the fucking, for the hills." That would have been especially useful testimony in the trial, except for the fact that King hadn't mentioned it earlier.

Lerman explains that Rodney was afraid at first to charge racism because he thought the police might railroad him into jail and never let him out. He also says that Rodney's mother requested that race not be made an issue in the case.

Then why did Lerman subsequently charge racism so loudly? Lerman's critics, including the district attorney's office, lay it off to inexperience in civil-rights cases, and the mistaken belief that racial animus has to be part of a violation of rights. (In fact, most excessive-force claims are based on a section of the U.S. Code that says nothing about race; rather, the civil right being violated is the individual's Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure.)

Lerman says he brought race into the case after hearing a sound-enhanced version of the Holliday videotape on which the racial epithets could be heard. The district attorney's office, which also hired a sound-enhancement expert, says that no racial taunts could be discerned. "I don't think this is malicious on Rodney's part," White says of King's changing story. "I think Rodney's been manipulated to believe these things. And I don't know if it's just Steve Lerman. I think he's been around so many people he actually believes what he is saying now."

White also faults Lerman and his associates for accompanying King to meetings with the D.A.'s office, where they would "help" him answer questions. "We'd ask Rodney a question, and Lerman would say, 'Well, you remember you told me, Rodney. . . ' I didn't know where Rodney's memory started and Lerman's memory ended."

White finally got his time alone with King in late January, with the trial nearing, and he did not like what he saw. King was inarticulate, moody, inconsistent in his answers, and quick to anger at what White considered the easiest lobs. "You could see the anger and the frustration, I mean a lot of anger, coming out during these questions. And he was still on medication at the time. . . and he was getting very angry about these really not very hard questions."

White imagined the impact on the jurors if King were to lose his temper in court. And then, when the trial started, something happened that sealed his decision not to put King on the stand. Melanie and Tim Singer, the husband-and-wife Highway Patrol team, testified that they had not struck King. "Lerman calls me on a Saturday morning and says, 'Rodney wants to talk to you,' " White recalls. "And Rodney got on the phone and he was a very angry person. Profanity spewing out. He was angry, saying, 'Melanie Singer kicked me, Tim Singer kicked me, and they're lying!' It was 'Fuck this,' and 'Motherfucker that,' and right then I knew we had made the right decision."

The defense team later said it had earnestly wished for a chance to go at King on the witness stand. "We were very disappointed in the prosecution's decision not to call him," says a member of the team, John Barnett. "We really would have enjoyed cross-examining him." The irony is that, no matter what sort of witness King made, the violent aftermath might have been avoided if he had testified. If he'd been a convincing witness, he might have clinched it; if he'd been as bad as White feared and defense lawyers hoped, he'd have been discredited and the acquittal would have been less shocking.

King may yet tell his story on the stand, when Officer Laurence Powell, who was not acquitted by the Simi Valley jury, is retried. But many doubt that a federal case, revived by President Bush in the politically charged hours after the acquittal, will ever materialize.

Which leaves King's multimillion-dollar civil-rights suit. Scheduled for October, it may never reach court. Lerman wants a settlement for King, and the city seems eager to oblige.

City Attorney James Hahn is said to be more worried about winning the case in court than losing it. "That's a hell of a bad settlement posture to be in," observes one attorney associated with the case. " 'If you don't settle with me, there'll be a riot.' "

In early settlement talks, there was some distance between the two sides: a source reports that the city offered $2 million, with a hint of going to $3 million, while Lerman asked for $10 million plus an annuity, which would give King an income for life.

Even if the city does come much closer to Lerman's figure, say, $7.5 million, King will see only a portion of the settlement money. First he'll have to pay off his lawyer, and if Lerman has the usual one-third contingency agreement, that will make his fee about $2.5 million. If Lerman deducts cash advances made to King, the cost of the twenty-four-hour security force, living expenses, and so on, King's take will be shaved even further. He will also likely have to pay the considerable medical bills he has accumulated from private doctors—including the psychiatrist, a plastic surgeon (he's already had facial reconstruction), and a neurologist.

While the two sides haggle, Rodney King remains in his cocoon, safe from incident, and from rival lawyers. James Banks is keeping vigilant watch over Triple-7's investment, and Aunt Angela is still stewing over the family's being shut out in the Rodney King sweepstakes.

"Everybody else is out there making money with Rodney King and no one's saying nothing. And here I am, the main source of the family, and you gonna tell me I can't make a few T-shirts and sell them? I talked to Rodney about it. He told me. . .if I could make some money for the family, then go ahead, because it'll be a while before he'll have any."

In May, Angela finally decided to go ahead and get into the Rodney King business on her own. She cut out a picture of her nephew from the newspaper, traced it onto a white T-shirt, and painted on his hair and mustache. She planned to sell the shirts for six dollars—a bargain next to the bootleg Rodney shirts that sell in South-Central for ten dollars.

But then she got a message on her answering machine that caused her to reconsider her T-shirt project. The call was from James Banks at Triple-7.

"Apparently," said Banks's recorded voice, "some people are selling T-shirts of Glen. . . . As I'm sure you're aware, the rights for Mr. King are with my client. . . "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now