Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWOMAN OF HER YEAR

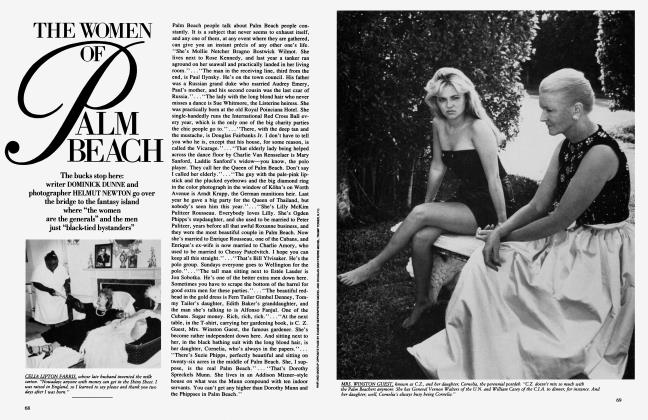

Columnist Dorothy Thompson was overbearingly brilliant and charismatic—the intellectual toast of the turbulent thirties. Henry Luce called her America's most influential woman after Eleanor Roosevelt. She was the first correspondent Hitler deported. And Katharine Hepburn portrayed her in Woman of the Year. But as PETER KURTH writes in an excerpt from his new biography, American Cassandra (Little, Brown), as Thompson's career soared, her marriage to Sinclair Lewis crashed

PETER KURTH

In 1939, Dorothy Thompson appeared on the cover of Time, magazine, which hailed her as "undoubtedly the most influential" woman in the United States next to Eleanor Roosevelt. Her hard-hitting, opinionated political column, ' 'On the Record, ' ' was syndicated to more than two hundred newspapers, and her NBC radio broadcasts reached millions of Americans each week.

Her career had moved from war-ridden Central Europe, where she started out as a freelance reporter in 1920, to the cafes and chancelleries of Weimar Berlin. Until she was thrown out of the country by Hitler—the first correspondent to be so expelled— she watched and reported the rise of the Nazis. During the 1930s, she emerged as a latter-day Cassandra whose mission it was to rouse America to the menace of Hitler. ' 'She has shown what one valiant woman can do with the power of a pen, ' ' said Winston Churchill. ''Freedom and humanity are her grateful debtors."

Her marriage to Sinclair Lewis— ''Red"—was one of the most volatile and well-publicized unions of the century. (It was satirized by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in Woman of the Year.) They met in 1927, and for a short time, before the Nazi advance gave her an international platform, Dorothy was content to surrender her own career for Lewis, motherhood, and a reputation as the brightest hostess in literary New York. But as Red's career declined in a spiral of alcoholism, her own star rose higher and higher, until the name Dorothy Thompson was as familiar to the American people as that of Franklin Roosevelt or J. Edgar Hoover.

The following excerpt, from Peter Kurth's biography American Cassandra (out next month from Little, Brown), begins at the height of Dorothy's fame, just after the debut of her syndicated column.

Red left her, more or less permanently, when "On the Record" was about a year old, at the end of April There was no immediately identifiable provocation for the break and no better explanation from Red than that Dorothy's work—and her stupendous success—had "ruined their marriage" and "robbed him of his creative powers." He stood "quite cold and quite possessed" in the front hall of their house in Bronxville and told Dorothy with a straight face that she was to blame for his diminished productivity, and that he wanted a separation in order to rescue his career from oblivion. "I want to go away," Red announced, "and be by myself for a couple of years."

"Who in hell does he think he is?" Dorothy demanded to know, quoting her inmost thoughts in one of those lengthy, deliberative letters that always accompanied the ruptures in her life. "He has written a whole shelf of books and four of them, certainly, and probably more, are classics of American literature already. Or five, or six. One would be enough for a normal genius.

... Sometime, he will have to resign himself to sit under the vine and ruminate on the past." Between 1935 and 1937, in fact, Red had completed one novel, a number of essays and short stories, some criticism, a bad play—the illfated Jay hawker—and a good one, the stage adaptation of It Can't Happen Here. The truth was that Red had been unceasingly creative ever since the publication of Ann Vickers, and the excuses he gave Dorothy for wanting a formal separation were only that: excuses.

"This business that you have built up now in your mind about me and you," she chided him from Bronxville, "about being the husband of Dorothy Thompson, a tail to an ascending comet and whatnot, is only because you are, for the moment, stymied, and you have been that many times before.... I know all about you, my darling. I know what is eating you and [what] always, periodically, has eaten you." So far as Dorothy could tell, Red had been more amazed than disturbed by her mounting celebrity. Frequently he had helped her edit the columns in "On the Record"; he almost always had something constructive to say about them, and occasionally had to be stopped from reading them aloud, over and over, to his friends and dinner companions.

"He was fascinated by the power of the telephone company," Brendan Gill remembered. Red assured everyone in earshot "that he had only to say to the operator, 'Get me Dorothy Thompson,' and they would promptly 'get' her, although she might be hundreds of miles away." His jokes about Dorothy's prominence were becoming famous throughout America. He told all sorts of people about an improbable Sunday morning when he had answered the telephone in bed and, hearing a White House secretary at the other end of the line, handed the receiver to Dorothy. For half an hour, Red insisted, he had lain there with the telephone cord stretched tight across his neck while Dorothy and the president talked about foreign policy.

"Let us not discuss it," Red pleaded with Dorothy whenever he got home and found guests in the house. "I mean, let us not discuss It. O.K.?" By this time, everyone knew what "It" was, but evidently Red's humor was only a mask for his genuine discomfort. "He had a horror of being known as 'Mr. Dorothy Thompson,' " Dorothy's fellow journalist and close friend Jimmy Sheean explained, "and in one way or another this phobia was made known to all of his friends." Dorothy herself told a story about a hairdresser in Los Angeles who was reluctant to extend credit to "Mrs. Sinclair Lewis," but not to Dorothy Thompson.

"Are you Dorothy Thompson?" the young woman asked.

"That's my name," said Dorothy.

"Well, why didn't you say so? Of course you can charge it." It was just the kind of thing—ridiculous, but more and more common as time went by—to nourish Red's towering paranoia.

"I couldn't help being on Lewis's side," said John Hersey, who worked as Red's secretary during the summer of 1937. "I must have been too young to recognize the bitterness of an exhausted gift, and of course I was ignorant of the drinking history. Dorothy Thompson seemed to me an overpowering figure in a Wagnerian opera, a Valkyrie, deciding with careless pointing of her spear who should die on the battlefield. Some things about my boss's home life, if it could be called that, did make me uneasy." Jimmy Sheean's young English wife, the talented and beautiful Diana Forbes-Robertson—"Dinah" to her friends—met Red around the same time as Hersey and remembered that Red had become "almost sheepish" in his attempts to put himself forward. "I wrote a book once," he remarked with a sigh, then shouted amiably in Dorothy's direction, "Dotty! Don't lecture!"

"Red was charming to me," said Dinah Sheean. She did not recall ever having seen him drunk, and retained only the warmest and most happy memories of his company: "He made me feel important, which I wasn't. With Dorothy, I was more or less invisible, just 'Jimmy's wife.' " This proven ability on Dorothy's part to ignore the feelings of other people, her reluctance to acknowledge, sometimes, that they were even in the room, infuriated Red more than anything else.

Sinclair Lewis "had a horror of being known as 'Mr. Dorothy Thompson.' "

I have a terrible impulse when I'm with Dorothy,'' said a woman of her acquaintance, "to suddenly stretch my mouth with my thumbs, push my eyebrows up with my fingers, and shriek, 'The cat is on the mat!' I'm positive Dorothy wouldn't notice anything out of the ordinary." It was not unusual for Dorothy to greet her guests at the door, when she had invited them for dinner or a late-night party, with a bright smile and the words "How are you? You look wonderful. You simply must hear my column. It's terrific—the best I've ever done. Listen!" And she would launch into a reading, unabashed even when encouraged only by the most perfunctory nods and sighs of admiration. She frequently laughed aloud at her own humor, and common wisdom held that if there were nobody present to laugh with her she would laugh by herself.

Wives sat in a cold fury while their husbands formed a ring, literally, at Dorothy's feet.

"Often," said Dale Warren, her editor at Houghton Mifflin, "very often, she appears to regard those within earshot as constituting a lecture audience, and proceeds at length to deliver (in private or semi-private surroundings) what is regarded as a public lecture. What she is really doing is using present company as a sounding board in an effort to clarify her own ideas." In Dorothy's defense, it should be stated that it was never the sound of her own voice alone that held her in thrall. She invariably had "a literary passion" going, and anyone who came to dinner at her apartment on Central Park West could count on a fireside recitation from Leaves of Grass or some book of philosophy Dorothy was reading, an article in Foreign Affairs or a novel she admired. She was extremely generous with information and ideas, and was sincerely interested in advancing the reputation of anyone whose work she thought was important. "She can do more for a cause than any private citizen in the United States," said Time magazine, and if she talked too much, it was best put down to a kind of amnesia, or the natural and somehow forgivable abstraction of a very busy mind.

Her manner in conversation was normally calm, unless, as The New Yorker reported, "people turn out to be as stupid as she expects them to be," in which case she was apt to shout out "Pah!" and "Pooh!" and "Don't be ridiculous!" without thinking that anyone she was talking to might be offended.

Many people were. Women, in particular, were annoyed to be treated as ciphers in Dorothy's company; the wives of her colleagues and unofficial advisers sat out many an evening at Central Park West in a cold fury while their husbands formed a ring, literally, at Dorothy's feet. "To hold a conversation," said Louis Nizer, her attorney, "you must let go once in a while. She rarely did. She lectured and we learned and enjoyed it." She was the mistress of a private "brain trust," a varied network of political theorists, economists, journalists, editors, Cabinet ministers, agrarians, playwrights, publishers, and Broadway producers, who gave her their advice free of charge and were generally thought to be the hidden powers behind "On the Record." As time went by, Dorothy became eager to counter the impression, mainly in leftist circles, that she was a kept journalist and the white-headed girl of business interests. It was no secret, however, that she preferred the company of men to that of women, and when Henry Luce put her on the cover of Time, the caption under her picture read, "Dorothy Thompson: She rides in the smoking car. ' '

Even the furnishings at Central Park West seemed designed to put men at their ease. "No self-conscious period pieces remind the guest of the occupant's taste in antiques," wrote Jack Alexander in The Saturday Evening Post. "The chairs are deep and comfortable and of no more specific design than those in a men's club. The ash trays are capacious." The scotch flowed freely, and bowls of loose cigarettes lay scattered around the tables. "I wonder we ever saw one another," said a friend of Dorothy's, thinking back on the clouds of smoke that always hung in the air in her company.

A lexander Sachs, the beM spectacled, Lithuanian/M born vice president of / M Lehman Brothers in New / M York, was Dorothy's chief / M financial consultant for / M "On the Record," along JL with Frank Altshul of Lazard Freres and Gustav Stolper, whom she had known in Vienna and who, with his wife, Toni, formed an independent, two-person think tank on economic affairs. All of these people were political liberals and fiscal conservatives—dissident Democrats in the New Deal years— who gave Dorothy a sound training in the obliquities and caprices of international capitalism and high finance. It was not unusual for Dorothy to receive a twenty-page memo, even a direct outline for a series of columns, from one or another of her banking friends.

When she needed a legal opinion, she went to the "witty, tweedy, bow-tied" Morris Ernst, the liberal activist and future board member of the American Civil Liberties Union, who in 1933 had successfully undertaken the defense of James Joyce's Ulysses against obscenity charges and thereafter enjoyed, in perpetuity, a lucrative royalty from the Joyce estate. The New York Times described Ernst as "a man of lively, jumping mind, curious about everything, skeptical about many things, liberal in all his general assumptions, maybe too free in passing judgments in a few fields in which he [was] not professionally versed." He was, that is to say, much like Dorothy, and William I. Nichols, who later went on to edit This Week in New York, remembered a night at a party when Dorothy and Ernst sat together on ai sofa in the middle of the room and "talked at each other, simultaneously, uninterruptedly,'' for more than twenty minutes.

Continued on page 162

Continued from page 154

The membership of Dorothy's brain trust was fluid and constantly changing, because any authority she met in any field was likely to be pumped for information within an hour of their acquaintance. "Oh, that's good!" she sometimes exclaimed in the middle of conversation. "Can I have that?" She was criticized for "brain-picking," but answered the charge by saying that no one person could possibly be expected to know everything, and only a man would try. "To the best picker" belonged the brains, said Dorothy; it was just too bad that there weren't more of them. She had access to the Roosevelt administration through Frances Perkins, Robert Sherwood, Harry Hopkins, and Jerome Frank; a line to Hollywood through Arthur Lyons; an adviser on education in Dean Christian Gauss of Princeton University. Wendell Willkie advised her on utilities; David Samoff on communications and entertainment; Harold Nicolson, Herbert Agar, and Hamilton Fish Armstrong on foreign affairs.

In addition, Dorothy was never far from her familiar circle of crack reporters and foreign correspondents—especially Jimmy Sheean and John Gunther, who were both enjoying a fantastic success on the home front, the equivalent of superstardom, John with the first of his "Inside" books and Jimmy with Personal History. If Dorothy could not always be counted on to cite her sources in her column, she never quoted anyone directly without permission, and the regularity with which she did use quotes gave the lie most dramatically to the accusation that she never stopped talking herself. Being summoned by Dorothy Thompson, the saying went, was like being asked to lecture before the French Academy: you had the best audience in town, and your words were bound to turn up in print sooner or later.

"I was delighted to find a phrase or an idea of mine—mostly on Fascism—in one of her columns," said Max Ascoli, the Italian journalist and refugee from Mussolini who went on to become editor of The Reporter in New York. "I was just writing for The Yale Review and other smallcirculation magazines in those days, and I was glad to have a wider platform... . Sometimes Dorothy and I would go around the comer to an Italian restaurant—it had been a speakeasy—for dinner. Then we'd go back to her place and sit up, sometimes till four in the morning, talking, with Dorothy writing away furiously on her golden pad."

O he was seen more and more often in Othe company of men like Ascoli, Raoul de Roussy de Sales, the brilliant liberal aristocrat who was the correspondent in New York for Paris-Soir and other French newspapers, and the ruddy, blueeyed Peter Grimm, the real-estate developer who gathered together the properties in midtown Manhattan that formed the site for Rockefeller Center. With all three of these men Dorothy was reputed to have had affairs, and with all three of them she possibly did. She was seen in their company dining at "21," whisking up and down the aisles at the Philharmonic, speaking at testimonial dinners, and applauding at Broadway premieres. She had become, in the late 1930s, almost preternaturally beautiful—"radiant," as the wife of her agent, John Moses, remembered, "statuesque" and "gorgeous" in her Bergdorf gowns.

"She became beautiful," said a woman who met Dorothy in 1939. "Literally, she shone with success and power." She had never been interested in fashion, but she got used to being complimented on her appearance, and every six months or so she would sally forth in a taxi and come home with a half-dozen expensive new evening dresses, two or three conservative red hats, dozens of pairs of high-heeled shoes, and, when everything was tallied up, "an uncommonly varied collection of fur coats." These she proceeded to wear casually, almost sloppily—"as if she were impatient with the necessity for bothering about clothes," wrote Jack Alexander. "A watchful observer gets the feeling that she puts them on hastily and then forgets about them, and that the tilt of her shoulder straps may be imperiled by her next gesture." In a letter to Alexander Woollcott, whose summer place on Bomoseen Lake, in Vermont, was not far from Twin Farms, her country house, Dorothy complained that she was never depicted "as a woman" in newspaper and magazine profiles. She was tired of being told that she had "the brains of a man."

"What man?" she wondered. "My strength is altogether female.... I wish somebody would say that I am a hell of a good housekeeper, that the food by me is swell, that I am almost a perfect wife, and that I am still susceptible to the boys. That's all heresy which the feminists wouldn't like, but it's a fact.... Work with me has always been a by-product and a secondary interest. I'd throw the state of the nation into the ashcan for anyone I loved." No one who knew her could take these protests seriously (they were always fleeting, in any case), but neither did the men in Dorothy's entourage deny that she was "a magnificent animal," an intensely female presence, "a woman you felt it would be fun to go to bed with."

"Suggestions that her incessant intellectual gymnastics obscure her feminine qualities irritate her a great deal," the writer Charles Fisher observed. "Miss Thompson's feeling appears to be that despite the excessive numbers of her gray cells and the responsibilities she has shouldered, she is all frail womanhood, by God, and anybody who doubts it can look for a clout in the ear." She was "the worst-photographed woman in America," said John Gunther; in her own estimation she always came out looking like Sophie Tucker. Only the people who knew her personally could have had any idea how lovely she was—how her flawless, rosesand-cream complexion had combined with her blue eyes and her prematurely white hair to make her look like a Nordic goddess. Dinah Sheean's first memory of Dorothy was of watching her at a party at the Hotel Lombardy, laughing, "tossing her leonine head in that way she had," and "seeming to look down on everybody from a great height.

"She wasn't haughty," Dinah pointed out, "just high." According to Klaus Mann, the German writer and son of Thomas Mann, Dorothy had begun "to assume the appearance of a Roman empress, whose imperious charm we can still admire—not without respectful trepidation—in certain busts of the decadent period." Everything about her was "machtig," said Mann—"powerful": "Every time I see her I am spellbound anew by that electrifying force she emanates." These comments were recorded in a private diary and were not hyperbolic. Dorothy was "incapable of doing the simplest acts without infusing drama into them in some way," Jack Alexander remarked. "Her friends say that she snips her nails with indignation." Poets and movie stars were no less enthralled with her than were journalists, writers, and professors of economics. The radio personality Ilka Chase watched in amazement one evening as the great Arturo Toscanini ran up to Dorothy at a party in his honor and "greeted her with a warm kiss."

"I am living on quantities of adrenaline, from the fury I feel at every waking moment."

Dorothy "observed complacently that he always did that," Miss Chase remembered, "because she was the one person who didn't fuss over him."

T n 1939, in an "On the Record" colJLumn, Dorothy drew up a list of the twenty people she would invite to "the perfect party" if she had the chance. It included Helen Hayes and Katharine Hepbum ("on account of such modest earnestness in the midst of so much good looks"); the comedienne Beatrice Lillie (who was "the funniest woman alive"); Helen Reid of the Herald Tribune; Alice Roosevelt Long worth; the beautiful and enigmatic Eve Curie, daughter of Marie Curie and "a woman who [had] everything," in Dorothy's eyes, and who enjoyed a famous romance with the French boulevardier Henri Bernstein; the pianist Ania Dorfmann; the artist Neysa McMein; Noel Coward; Charlie Chaplin; Clare Boothe Luce (who was already at every party in New York and could "discuss politics, letters [and] fashion with equal vivacity"); and Dorothy's "personal favorites," Sir Wilmott Lewis of the London Times and Stringfellow Barr— "Winkie" to his friends—the president of St. John's College in Annapolis.

"Sinclair Lewis can come to any of my parties," Dorothy added in a wry exercise in public relations, "and not because it is his right. Nobody living talks better if he likes the party; nobody can kill a party sooner if he doesn't. But he'd like this party.. ..

"And as for Dorothy Thompson," she concluded, "she is terrible. She always talks politics and has a horrible habit of holding forth. Given the slightest opportunity she makes a speech, and nothing that she says to herself in the cab on the way home seems to cure her." Dorothy's reputation for logorrhea—tongue wagging for tongue wagging's sake—was so secure that it became the butt of jokes even overseas. Closer to home, Waverley Root, who at that time was a member of the Association of Radio News Analysts in New York, remembered the dismayed reaction whenever it was suggested that the association open its doors to women: " 'We think we're liberal and up-to-date,' somebody would say. 'We ought to think about admitting women.' The response was always the same. 'Of course we should. But the first woman we would have to admit would be Dorothy Thompson.' Silence would fall, and after a moment someone would introduce a different subject of conversation."

There were always two or three guests at Dorothy's parties who hung nervously in the background, dreading the moment when she might ask one of them a question and expect an answer.

"Did you ever meet a nicer young man," she would mutter abstractedly when a tongue-tied newcomer had left the room, "—or a duller one?" She was lightning-quick when it came to recognizing a serious conversationalist, and her sincerest compliment, especially in characterizing another woman, was to say that she was "witty." "In men she looked for other qualities," said Dale Warren, "but regardless of the sex her preferences were for people who were 'gifted,' and responsive as well." Klaus Mann recalled the night when Dorothy sat up till dawn arguing with Henri Bernstein in Bernstein's apartment—"flashing, polemicizing, joking, explaining, vying for points." At about four in the morning Bernstein began to get tired, eventually winding up prostrate on the sofa, "finished," muttering in stupefaction about his beloved Eve Curie.

"Eve est incomparable!" moaned Bernstein from the couch. "Ah, comme elle est belle! Quelle femme! Elle est incomparable . . . in-com-pa. . . rable..." Dorothy, on the other hand, was growing "fresher by the minute," and only when the sun came up over the East River did she finally look at her watch, "put an end to her astonishing monologue," and depart with the words "My secretary is waiting for me. I have to dictate a couple of articles before lunch."

ry y 1939 she had three secretaries, all Dof them, funnily enough, called "Madeline." The spellings were different, but the pronunciation was the same, and, if nothing else, this allowed Dorothy to confine herself to a single brisk shout when she needed assistance. On an ordinary working day in New York, two of

Dorothy's secretaries could be found at her office in the Herald Tribune building, a place she herself rarely visited—"because the phone never stops ringing"— but had decorated tastefully, with globes and maps and a framed copy of the expulsion order that the Gestapo had issued for her in Berlin in 1934. Next to this hung a cartoon that James Thurber had drawn for The New Yorker. It showed two women staring, half tolerantly, half incredulously, at the husband of one of them, who was seated at a typewriter and visibly fuming. The caption read, "He's giving Dorothy Thompson a piece of his mind."

Ordinarily, Dorothy wrote "On the Record" in longhand, in bed, where she lay most mornings until well after noon, reading newspapers, telephoning friends, answering mail, drinking black coffee, and chain-smoking Camel cigarettes. One of the secretaries was always in attendance to take down her dictation, but unless she had other work to do—a speech or an article or one of her regular radio broadcasts—she preferred to write out the column by herself, and only when she was happy with the way it sounded would she rise and read it aloud to anyone who might be in the room. When a column was finished, it was hastily typed up and sent by messenger to the Herald Tribune office, where it was checked for libel and grammatical errors (but rarely edited otherwise) and then dispatched by airmail or telegraph to subscribing papers around the country. Dorothy was then free to rise, get dressed, and pace the apartment for the rest of the day, a yellow legal pad clutched tightly in her hand so she could easily jot down ideas as they came to her. Quantities of foolscap, as well as Parker pens and L. C. Smith typewriters, were scattered the length and breadth of the house because Dorothy never knew when she might "get curious" and need to write about something. She would keep on writing, annotating, telephoning, and talking things out until cocktail hour, when her friends would begin to drop in for drinks.

Three times a week, on "column mornings," strict rules of privacy and quiet applied in the household. In The Saturday Evening Post, Jack Alexander drew a portrait of Dorothy at work that entered the national imagination as no other could. Having agreed to be interviewed by a lady reporter,

she was sitting up, in negligee, in a bed that was strewn with newspapers, books, cablegrams and letters, and she was dictating her column for the next day. A secretary, seated at a typewriter, pecked out the dictation. Miss Thompson, talking as if addressing a mass meeting, was trying out phrases and sentences in various combinations until she was satisfied with their ring. She talked at a giddy clip, simultaneously brushing her hair in jerky sweeps. She used gestures for emphasis, waving the hairbrush in the air or bringing it down smartly on her free hand.

Fascinated by the spectacle, the visitor sat down near the door. When the column was finished, the secretary left the room and a maid came in with a breakfast tray of prunes, toast and coffee, and set it down across Miss Thompson's knees. The interviewer opened with a casual remark about a move which Germany had made the day before. The effect was as if she had touched off the fuse to a string of firecrackers. Miss Thompson, who thinks and has freely stated that Hitler is a maniac, launched into a rousing diatribe against Der Ftihrer and all other dictators. She delivered herself so forcefully that at times the tray rattled and the prunes jumped about in their saucer.

The caller was so taken by the sight of the volcanic columnist in eruption that she forgot to bring up a list of questions which she had prepared in advance. She came away convinced that she had seen one of the natural wonders of America at close range.

"I am living on quantities of adrenaline," Dorothy confirmed, "self-distilled, from the fury I feel at every waking moment. The fury I feel for appeasers, for the listless, apathetic and stupid people who still exist in this sad world!" She was living, also, on speed—Dexedrine pills and a variety of uppers that her doctors gave her in the belief that she could not function under such high pressure without assistance.

In 1938, Dorothy wrote 132 columns for "On the Record" (a thousand words each); twelve lengthy pieces for the Ladies' Home Journal; more than fifty speeches and miscellaneous articles; uncounted radio broadcasts; and a book, Refugees: Anarchy or Organization?, which she developed from an article in Foreign Affairs and which dealt with antiSemitism and the crisis of modem statelessness. Two collections of her columns were also published at around this time, one of them under the friendly, helpfulsounding title Dorothy Thompson's Political Guide, and the other as Let the Record Speak, which became a best-seller in New York and which The New York Times thought would have been better called Let the Record Shout. A reporter who interviewed her for The Christian Science Monitor looked over her shoulder while they talked and was staggered to see some of the titles on Dorothy's shelves: Meritism—The Middle Road; Dynamics of Population; Government Publications and Their Use; Political Handbook of the World—she needed every bit of assistance her secretaries could give her.

"Darling," wrote Dorothy to Alexander Woollcott at the end of 1937, "for no fee and not even for love would I make any more speeches than I have contracted to do this year. ... I speak so much as it is that I am emptying my not very competent

brain much, much faster than I can refill it." That summer she had been given her own radio program. Sponsored variously by Pall Mall cigarettes, the General Electric Company, Savarin coffee, and Clipper Craft clothes, Dorothy was billed as an "all-news commentator" for NBC's Hour of Charm, and for thirteen minutes every Monday night she broadcast what amounted to a topical swing session on any subject she chose. Her program was "not recommended for those suffering either from complacency or cardiac disorder," said Scribner's magazine. She had a way of punching her words on the air that was nothing short of electrifying, and her voice had by this time taken on a kind of thirties fruitiness that led one critic to describe it as "an intriguing blend of Oxford and Main Street." Anyone who read her column regularly knew the breadth of her interests, but on her radio program, at least until war broke out in Europe in 1939, she tried to limit herself to discussing "Personalities in the News."

She talked about the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, whose recent marriage in the South of France had capped "the romance of the century"; about Charles Lindbergh, whose open admiration of Adolf Hitler had begun to puzzle his compatriots; about Justice Hugo Black, whose appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1937 was accompanied by the revelation that he had once belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. If the news that week was dull (it rarely was), Dorothy might

turn her attention to the luminaries of history: Booker T. Washington, Clara Barton, Napoleon and Josephine. She talked about Ireland's prime minister, Eamon De Valera, and Mexico's president, Lazaro Cardenas; about Hjalmar Schacht and Andrew Mellon and a veritable stampede of Balkan royalty. On one occasion she had planned to discuss the career of Admiral H. E. Yamell, commander of the Pacific fleet, but on the same day Adolf Hitler named himself minister of war in Berlin, and she thought it much more important to explain to her audience exactly how frightening that was.

"What has happened today is a defeat," she said, "of the forces in Germany who have been trying to stop [Hitler's] wild adventures. . . . The German foreign

minister, Baron von Neurath, has been replaced by Joachim von Ribbentrop, ambassador to London. The ambassadors from Tokyo, Rome and Vienna have been recalled. At the same time, a new secret council has been formed. This is a war council, of course." After a while, Dorothy's sponsors began to worry about her "belligerent tone." General Electric, worried about libel suits, saw the need to issue a statement affirming that Miss Thompson's opinions were her own, and an effort was made to soften her diatribes by having Phil Spitalny's All-Girl Orchestra open the program with such reassuring tunes as "Love Sends a Little Gift of Roses" and close it with a soothing rendition of "Thank God for a Garden."

It was absurd, of course, but Dorothy would have gone to greater lengths than these to get her message across. She was so preoccupied with world events and the menace of Hitler that she even failed to notice, according to witnesses, the great hurricane of 1938, which swept through the northeastern United States in September of that year and caused particularly heavy damage in Vermont. Dorothy was in New York at the time of the storm, broadcasting editorials night and day in response to the Munich crisis and the Nazi dismemberment of Czechoslovakia; only after two days, while awaiting her turn at the NBC microphone, did she chance to overhear a weather update, realizing in one awful moment that Twin Farms— along with her son, who happened to be there—might well have been blown to smithereens.

But she was always distracted in moments of crisis. One night in 1939, just after the outbreak of the war in Europe, she was invited to dinner by Jimmy and Dinah Sheean. The Sheeans had been living that summer in the smaller "Old House" at Twin Farms, and another of their guests was the actor Otis Skinner, a Vermont neighbor and good friend of Dorothy's. Dorothy was expected at seven, but by eight she had not turned up, and eventually the Sheeans and Skinner sat down to eat without her. They were halfway through the soup when Dorothy suddenly appeared, framed dramatically in the doorway as the shadows of evening fell around her.

"Jimmy," she declared without any preamble, "the Russians are in Poland!"

"The startled silence that met this announcement," said a woman who talked with Dinah Sheean later, "reminded her of her manners, and she moved at once, flowingly, to Otis Skinner's side. 'Oh, hello, Owen dear,' she said."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now