Sign In to Your Account

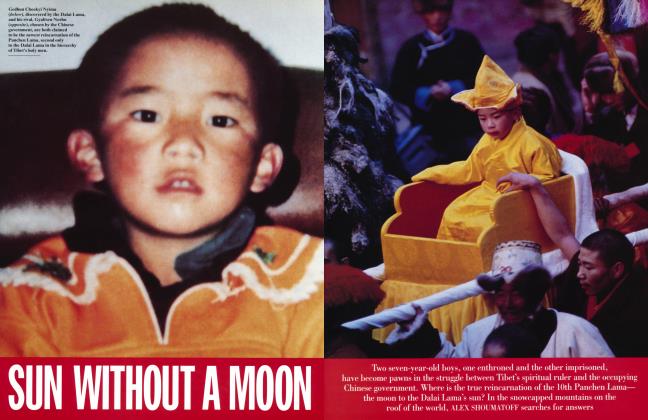

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAli Looks Back

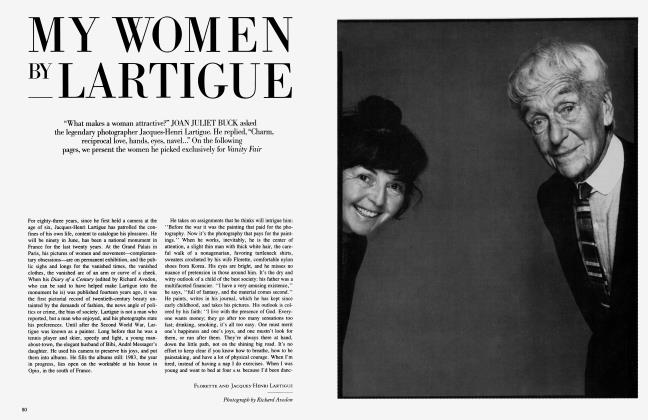

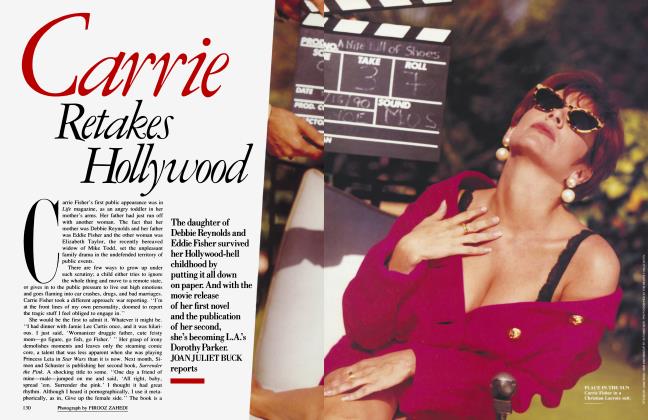

Why did Ali MacGraw abandon her identity as the biggest female star in America and the Hollywood-royal wife of producer Bob Evans to spend five long years as Steve McQueen's love slave? Now that the former golden girl has finally shaken her demons, she's working it all out in her new autobiography. JOAN JULIET BUCK reports

JOAN JULIET BUCK

Lunch was the dieting girl's special, a healthy salad followed by chocolate cookies, which, eaten without the benefit of plates, do not count. Ali MacGraw, chiseled, beautiful, and looking far younger than her fifty-one years, explained her life as Merlin the cat sat between us on the paisley draped across the table, calmly drinking all the water from her glass. Twenty years ago exactly she was the biggest female star in America, the only woman on a list that started with John Wayne and ended with Lee Marvin. As the star of two blockbuster movies, Goodbye, Columbus and Love Story, she was the savior of Paramount Pictures and the wife of its head of production, Robert Evans. She was on the cover of Time, depicted in the style of a Keane oil, with a banner over her head proclaiming "The Return to Romance." She was long and lean and she had style, she had an education, and, furthermore, she could draw. This last was so startling that Time captioned three of her funny little cartoons "just possibly miraculous." The world was in love with her.

A year later, the shooting of The Getaway put her together with Steve McQueen; the scandal created when she bolted with him made her the property of the National Enquirer, and then, by her own choice, she didn't work for five years. Things have never been the same. "I always remember," she said over the cookie crumbs, "that the next big superstar on the scene was Willard the Rat. ' ' At which point Merlin, up until then the soul of feline imperturbability, was beset by a coughing fit so fierce that his mistress had to stop everything to put some salve down his throat.

It's hard to live down scandals, and even harder to outlive them. Ali MacGraw is as long and lean and stylish as ever, more so because she stretches her spine with yoga every day and doesn't drink. American stars are allowed to exist only in relation to their success; the idea of a quietly plodding life that goes on no matter what is so alien to the structure of Hollywood thought that it comes close to resembling an austere ideal, life in a lamasery. Still, Ali MacGraw says she hopes to be able to answer the Hollywood question "What are you doing?" by simply saying, "I'm fine, thank you, leading my life." But she adds, "What they're really asking is 'Are you a thing or are you a nothing?' "

This month, her book, entitled Moving Pictures, will be published by Bantam. In it she chronicles her story in a series of vignettes leading up to her stay at the Betty Ford Center, and after. This casts the progression of past events and the description of her current life into a before-and-after schema, addiction and recovery. The addiction was not to drugs, and it remains a moot point to what degree it was alcohol. Although she writes that once she had stood up and said "My name is Ali MacGraw and I am an alcoholic/male dependent" she felt indescribable relief in "naming and owning the disease," it is clear that her addictions were to subtler and more dangerous things: to beauty, to illusion, to excitement, and to being in love. As with all people who have been through successful treatment for the portmanteau bugbear of their lives, she speaks in before-and-after terms, and the words "not anymore" are the almost automatic qualification to every story she tells. There's astonishing energy and overwhelming discipline in whatever she does, coupled now with a relentless defusing of the effect she makes. It seems that the habit she will never break is that of putting herself down; she says in the book that she is judgmental about others, but what comes across is steady, harsh judgment of herself. Even as she charms you into an open and complicitous simulacrum of friendship, she explains that she is guilty of attempting to charm everyone she runs across.

'Marrying Steve McQueen was the single most destructive act Ali could commit'

It's as if she had a compulsion to keep breaking the illusion.

She arrived in Hollywood ill-prepared, in that she knew perhaps too much for her own good. Not about money and ambition and power, and not about acting; about illusion. She was thirty, and had been for six years the stylist for photographer Melvin Sokolsky; she was one of the best, able to find an emerald-green Bugatti within an hour, or twenty-seven rusted wagon wheels, or to stage a train wreck. The scenes she set for Sokolsky's still lifes were meticulous creations of an ideal time or place. She knew how to fake life with props from behind the camera. She arrived in 1970, the star of the movie of the year, "having been to a few museums, read a few books, listened to some good music, speaking survival French and survival Italian," she says. This qualified her as an intellectual, as did having graduated from Wellesley and having worked for Diana Vreeland at Harper's Bazaar. To this day she is oddly apologetic about "wanting to visit the American Wing at the Met" or "beating them over the head with Mozart."

Five years ago, Irving "Swifty" Lazar told her she had a book in her, a phrase which in Hollywood carries with it a flavor of end-of-the-line, nothing-left-to-lose. At first she didn't know what to write; the framework was provided a year later by her visit to the Betty Ford Center, where confessional diaries are part of the program. This isn't a kiss-andtell book; names have been changed, and some identities blurred. However, the level of honesty far surpasses anything a publisher has a right to expect. I asked Lazar what had prompted his suggestion. "She's a remarkable girl," he said, "a cut above most movie stars. She's educated, which is unique. She's a woman who's had a lot of unique experience, and she married one of the most charismatic actors that ever was, and one of the most charismatic producers. And she's an interesting woman. She's au courant. She gets The New York Times every day."

Perhaps the tragedy was that she lived in a place where this is considered remarkable.

Her parents were both artists, bohemians who never worked in normal jobs, who had interned at Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin West. Her father, Richard MacGraw, of Scottish parentage, had run away to sea and then gone to art school; her mother's family was Hungarian, and her name was Frances Klein. "Was she Jewish?" I asked.

"She never answered that question," said MacGraw.

Her mother traveled around Europe and North Africa in the twenties, exploring and sketching; when she married, she did the commercial work and let her husband be the artist. He was a difficult man, and the extent of his misery is well documented in his daughter's book. He had been put in an orphanage as a child, and, she says, "his residual anger and pain had to get acted out on the only people he trusted, which was us.'' The family lived in the country in New York State, in a small house they shared with another couple; there was no money, no television, and no privacy. Both parents worked at home; the children's toys were paper and paints, and the family diversions were drawing, weaving, and making pottery. Her mother did layouts for catalogues, while her father was the misunderstood genius; he kept notes on flying saucers, in a script of his own invention, half Cyrillic, half cuneiform. He designed fabrics and made jewelry, some of which Ali would wear to school—"huge silver cuffs, in a town of circle pins.'' It sounds eccentric, more Bloomsbury than Pound Ridge, but while it made Ali creatively selfsufficient, there was also fear; her father was always "in a white-knuckle rage" because he had promised her mother he wouldn't drink, and he hit. "Fifty years later, somebody as bright as he would have gotten help," she says. Her parents had few friends and never received guests, but they taught her solid values about taking care of yourself, and an integrity that Time magazine could also have captioned "just possibly miraculous."

She started off studying English at Wellesley, but balked at Milton and "crossed the campus to the art department." As a guest editor at Mademoiselle in 1958, she was the cover girl. "Before settling down in some phase of commercial art, Alice wants to study art in Italy and sample fashion modeling," said the blurb accompanying her picture. Instead she joined Harper's Bazaar, and after working for Diana Vreeland for fifty-four dollars a week, she went to Sokolsky, who doubled her salary. There is usually a status cut between the models and the stylist, who helps the photographer make them beautiful. "Sometimes if a huge fuss was being made over a girl and I was on the floor with the pins, I'd think, Shit!" she says. Sokolsky sees it differently: "She wasn't the handmaid at all. A lot of models thought she was betterlooking than they were, so there was a lot of respect."

Candice Bergen was seventeen, a student at the University of Pennsylvania, when she did her first modeling job, for Clairol; the photographer was Melvin Sokolsky and the stylist was Ali MacGraw. "Ali was so clearly, instantly magical that the energy in the studio went up 100 percent when she strode through the door. I can remember exactly what she was wearing: low sling-backs and great tanned legs, and a bright, skinny flowered dress. She exploded into the studio like a megawatt bulb, all of that intelligence and generosity and energy and sexiness." They became friends years later, when MacGraw was married to Robert Evans.

Her own modeling career, which has been written up in terms of "top model" legends, was never more, she says, than a few commercials. Kitty D'Alessio, an advertising executive for, and later president of, Chanel, asked her to pose for a new bath oil. The photograph was taken in a rain forest in Puerto Rico, with MacGraw, hands held over her naked breasts, under a waterfall. "We were looking for someone with long hair who'd look like a water nymph when she was wet," says D'Alessio. "She had that combination of Scottish and Hungarian, Nordic and exotic." The ad became a display board, which Robert Evans saw in a drugstore. "That's the girl for Goodbye, Columbus," he apparently said. By then MacGraw had quit Sokolsky's studio and was taking acting classes. Barbara Nessim, who shared an apartment with Gloria Steinem and with whom Ali stayed from time to time, says, "I never knew she wanted to be an actress until she was in a movie."

In her first career she had proved herself in the New York marketplace of advertising and magazines. Kitty D'Alessio recalls, "She had so much talent she didn't know which way to focus it. She was a fantastic stylist, and could have been a designer, an editor, a decorator." To which Melvin Sokolsky adds production designer, art director, costumer, and line producer, the last for her "eye for detail and sense of logistics."

"My eyes work the best," says MacGraw. "I see very well, and that's the first thing I respond to." Sitting down to meals in front of the camera, she'd ask, "Why isn't there lipstick on this glass? It's half empty," or say, "Granny Smiths are great, but they'd be eating pippins." In Hollywood, an eye and sense of detail are required only by those whose job it is to make the illusion look real. Candice Bergen understands this: "Everything Ali does is guided by a sense of artistry. Hollywood stardom neglected, in a real sense, what is a huge part of her soul. That's what grounds and informs all of her sensibilities." Sokolsky, when pressed about the problems that might arise from passing from behind the camera to in front of the camera, from subject to object, admits, "Maybe you would always have a mind'seye view of what the camera was seeing, and if you thought about it, it would cause a strange interruption."

Jokes about Ali MacGraw's acting have become quaint banalities, like old smile buttons. Crack open Pauline Kael's collected pieces and you'll see her reviled. It's a surprise to watch Goodbye, Columbus again and realize that she was, in fact, terrific—beautiful, snotty, easy, imperious, with a confidence and a liquid grace that made her irresistible. "It was the last time I wasn't afraid," she says. After New York she never studied acting again. She was stiffer in Love Story, more awkward. Sue Mengers, the agent, says, "It's the awkwardness that made her a star. ' '

By The Getaway, she was palpably afraid. "Much as I admired him, Sam Peckinpah was not about acting. I was shrinking, recoiling, when they said, 'Action!' My mouth froze. Critics said, 'Will she stop flaring her nostrils? Will she stop locking her jaw? She is boring. She's supercilious.' It was all about fear. I was thinking, Oh, my God, everyone's looking at me. What am I doing here?"

Between Goodbye, Columbus and Love Story, she was living in New York with an actor, aware of the heat that was building around her as a new face, but unsure what would happen when Columbus opened. She had met Evans once, years before, when Eileen Ford set them up for an unsuccessful lunch. He had overseen the making of Goodbye, Columbus, and was producing Love Story. As Evans tells it, "She turned down The Adventurers. She was teaching remedial reading in Harlem. She didn't have two nickels to rub together, but those were her priorities." She flew out because he offered to show her a film by the director he'd hired; she arrived at his house for a screening and a brief, overnight stay. Evans says, ''We never saw the picture, and she never left the house."

She broke up with her boyfriend over the phone and returned to be with Evans in Los Angeles. "I remember," says MacGraw, ''taking a late plane, and looking out the back window of the limousine at New York with a sapphire-and-diamond engagement ring on my hand, and seeing these rays come off the ring. I started to cry, because I was leaving home."

She describes the Hollywood she moved to in terms of Evans's house: ''neo-Regency on a big piece of land, with a three-hundred-year-old sycamore tree that was being fed intravenously. I had never seen such opulence, ever—the fires lit, breakfast in bed, scented candles. Every single second of it was new, even the linen closet, which was full of incredibly beautiful cotton sheets and hundreds and hundreds of bars of Guerlain Fleurs des Alpes soap. Bob's dressing room had three mirrored walls, millions of clothes, a wall of shirts. My clothes only took up half a closet."

Since she had arrived with no clothes at all, Evans's first move was to get her twelve pairs of trousers from Holly Harp, one of the in boutiques of the time. ''She got on the best-dressed list with a wardrobe that cost $1,100 in all," he says proudly.

There was a kindly butler, and a less kind housekeeper. She had no friends in Los Angeles and knew no one but her husband. ''I had never, ever been taken care of, and here I was going to be taken care of by someone nice, who was so beautiful. Twenty years ago he was handsomer than anyone I knew. And he did something I have never experienced since: the more famous and the more sought-after I got, the better he felt about me. Whatever the dynamic of that was, whether it was having the shiniest possession on the block—I think it was a mixture of a lot of stuff—it was great, because I didn't need to sit on myself. But I do remember feeling that there wasn't a comer of the house that was me; there wasn't a postcard of Venice stuck in a frame in the bathroom... "

Love Story was shot in New York and Boston; in Los Angeles she had little to do besides being the hostess. ''I made a priority of charming everyone. The whole board of Gulf & Western [Paramount's parent company] would come to dinner, and I would make sure to gush over everybody. It was my downfall, such a sellout in terms of energy, because I lost myself. It was entirely about 'What do they think of me?' It was borderline lying, but it's O.K. It's my past and I'm conscious of it. I don't do that now."

They were a dazzling couple then, sort of young American royalty. In August 1970, my parents took me to Dino De Laurentiis's birthday party at a raucous outdoor restaurant near Menton called Le Pirate. De Laurentiis had a deal with Paramount at the time, and MacGraw and Evans were the stars of the evening; they came in a little late, and everyone, from Rizzoli pere and fils to the Italian actors to powerful men and their suntanned wives, sprang to attention. Ali MacGraw wore a long pink dress that may have been antique, and an embroidered band across her forehead. He wore black-tie. The waiters, dressed up as pirates, made wild sorties onto the tables from overhead ropes, to throw full bottles of Dom Perignon onto the rocky beach below, and plates and chairs and ashtrays, as the women rescued their minaudieres from the onslaught. It was a crashing, rollicking, high-octane night; Dino De Laurentiis was then the most generous and theatrical of hosts, with Silvana Mangano, remote, elegant, and sad, as his dignified counterweight. But, throughout the crashing and the smashing and the effusions, everyone was careful with the Evanses. It seemed that, for all the dancing on the tables, De Laurentiis didn't want their glasses smashed, or the space around them disturbed. As if the glossy bacchanalia had been put on to entertain, but not involve, them. Ali, whom I knew very slightly from New York, was warm and friendly, and inquired about a mutual friend with a concern and an intensity that I myself hardly felt for the person. I was astounded. She was a star, she was a bride, she was in pink, and she was talking to me.

"I was so busy editing Godfather that I left her alone for five months. With Steve McQueen!'

Continued on page 202

Continued from page 195

Of those days she says, "I was so scared to walk into those parties unless I had a really show-off outfit that I did a lot of exhibition dressing. I was in heavy costume, lots of headbands and ethnic stuff. Bob was great at that. He loved my costumes. I loved old clothes; short of having a million dollars, you couldn't duplicate those fabrics or those cuts. There was a beaded bag that I wore on my head; it was large for a bag, but so tight it gave me a blinding headache; there was a border on it that was just right. Somebody stole it; it was a size I'll never find again." Having become the exhibit, the stylist now styled herself, a logical and pragmatic move. But today she says, "Now I realize it was really attention grabbing." One longs to ask what was wrong with giving them a good show, but MacGraw has an investment in the notion of having put many things behind her. The costumes, Fortunys and Poirets, net shot with silver, are folded in a trunk in the second bedroom of her house, a spare and well-proportioned rental in one of those rare enclaves in Los Angeles where the geography suddenly pulls in tight enough to look like Europe. Her garden drops away behind the house, from which you can see a large expanse of ocean. An old and ailing golden Labrador lies on the tiled floor; a densely packed Scottie shoots about like a Cubist toy; a silky, retrieverish pound dog wiggles around requesting affection. An old wooden Madonna hung with silver necklaces stands guard on the mantel, and a piece of Javanese fabric in a strange and irregular pattern of blue and gold lies on a table, about to go up on a wall. There is no ostentation; the illustrated children's books she grew up with are in a bookcase in her study, along with her parents' sketchbooks and her own. There are many photos of her with her son, Joshua, a tall, high-cheekboned actor who was bom one month after Love Story opened.

"The sudden rush of being a pop star was like a cannon going off," says MacGraw. "It was an indescribable shock to be on the other side after groveling around for pins. For three years we could do no wrong, and to this day if I walk on a plane with one kind of ticket, I get upgraded. The perks of being a movie star are so extraordinary and so spoiling, and a couple of decades of them are hard to take."

Sue Mengers of ICM became her agent after Love Story opened—the Evanses' Christmas gift to her, as she puts it. MacGraw had earned $10,000 for Goodbye, Columbus and $20,000 for Love Story. The only part she wanted was Daisy in The Great Gatsby, which Evans had bought for her. It was in the works, but his business at hand was Francis Coppola's The Godfather. He persuaded her to do The Getaway with Steve McQueen, who was the biggest male star around. The money was $350,000. "With Ali, the problem was convincing her to work," says Sue Mengers. Joshua was one year old, and she didn't want to leave him. She gave in to her husband and her agent and went to Texas to do the movie.

Today, Evans recalls, "She always said, 'Don't leave me alone for more than two weeks,' but I never took her advice. I was busy climbing a ladder. I took her for granted. I was so busy editing Godfather that I never went to visit her on location. I left her alone for five months. With Steve McQueen. Do you call that ego?"

The progress of their affair is told in the book. The details are horrifying, such as the night McQueen spent with two girls he'd picked up, after which he asked MacGraw to cook him breakfast. "I went in and cooked it," she writes.

Mengers gave her the advice those who know her have heard a million times, with different names. "You don't have to marry Steve McQueen; just have an affair with him."

MacGraw fell in love, wildly. "Steve presented himself as such a pure soul, and here he was, the most powerful, biggest superstar in the business, and I thought, God, it can be done; you can really Not Sell Out. That's who I thought he was, and the reason I was so available for him was that this little voice had been saying, 'You're becoming a phony.' "

Where Evans had bought her pants by the dozen, McQueen said, "You have a great ass, but you better start working out now, because I don't want to wake up one day with a woman who's got an ass like a seventy-year-old Japanese soldier." She had no clear picture of that image, something to do with flatness, but she began to work out, "obsessively," she writes, four or five times a week. Ten years after McQueen's death, she still does.

The New York opening of The Godfa- ther was a great night for Evans; he sent the company jet to Texas for his wife, and they danced together at the St. Regis party afterward. She was already deeply involved with McQueen; in the photographs of that night she is dancing close with Evans, apparently happy and in love with him. "Part of me performed appropriately and sometimes even brilliantly—much more so in life than I usually did on-screen," she writes in the book. Of that night, she writes, "I felt like a piece of garbage." A few months and many dramas later, she bolted to McQueen.

"He only married her for one reason," says a well-known Hollywood actor, "because he wanted to take the golden girl of Hollywood and make her a maid."

"Ali's fantasy is the lady and the cowboy," says Sue Mengers. "She, who is so cultivated, with such exquisite manners, must enjoy either the contrast or the punishment. Bob at least was open to her taste; with Steve she had to play a role that was the opposite of what she is. Marrying Steve McQueen was the single most destructive act Ali could commit. Three big pictures in a row is no accident. She was as hot as Julia Roberts is today, and more mature. She gave up her career at its height, and it made me crazy. I thought, She's taken her golden years and she's throwing them away bringing him a beer!"

Even Neile McQueen Toffel, Steve's first wife, whose book is called My Husband, My Friend, writes, "Because she was so in love with him, Ali failed to recognize the dark side looming at her. All she allowed herself to see was the facade. ... He projected honesty as if he had invented it, when in fact he was a master of psychological manipulation."

As MacGraw sees it, "he'd done Hollywood to the eyeballs and wanted to get out. But, of course, here was a man who wasn't too thrilled when nobody knew who he was." They lived at Broad Beach, much farther from Los Angeles than Malibu; he wanted to see only bikers. She turned down every offer of work for five years. She enjoyed thinking of him as her wild man, of herself as his old lady. She no longer saw her old friends; she and McQueen were referred to as hermits. "I should have said, 'I do not want to stay in the kitchen night after night making hamburgers and mashed potatoes,' but the truth is sometimes I was really happy to do it. I thought he was being paranoid and a little bit theatrical; later I understood he couldn't walk down the street without that superstar heat." She thought of him as someone with whom she would be safe in the woods, as a survivor with earthier skills than style and French. Like her father, he had been abandoned by his mother. "The damage that was done to Steve in childhood was so huge, and I feel sad that I wasn't smart enough to handle it. I literally think that that kind of pain, untreated, is irreparable."

He had made it clear from the beginning that he did not want her to act in any more films; she obeyed. He was "somewhat stoned" every day;.she didn't smoke grass, a result of growing up in a small house with parents who each smoked four packs of Chesterfields a day. "It made a gap between us, like two different languages. Arabic and Finnish. My high energy would annoy him when he was mellow." She was disappointed; their ideas of pastimes didn't coincide, either. His culture was old cars and fast bikes; hers was music, books, art, travel. "We lived totally separately in that sense. The good stuff that was shared was his stuff, and when I was in the mood to go up on Mulholland with the bikers, it was wonderful.

"We were both tough to live with; it wasn't sane Ali ministering to the difficult movie star, but I thought I was being wonderful in the house. I never made up a list of what was important to my breathing system, and if I got into a thing that didn't interest him, I felt rejected." He had said that he wanted his old lady barefoot and pregnant in the kitchen; she was barefoot, and miscarried.

"He hated women drinking, because his mother had been an alcoholic. He'd give me a strange look if I had a glass of wine, so I didn't drink much, because I didn't want to appear repulsive in his eyes. He was so attractive, and everyone was so attracted to him that I didn't want to feel ugly and undesirable. I tried to do what would make him say, 'She's really hot.' Then I went into therapy and ranted and raved to a doctor who never said anything, and I was very sad a lot of the time. Here was this incredible man, and I wasn't cutting it for him. I didn't stop to think that he wasn't cutting it for me."

Candice Bergen was one of the few people to see her during those years; she'd go out to the beach, and the two would take long walks together. Sue Mengers was estranged; she could never get through on the phone, because, as she says, "Steve didn't like it if it was a secretary who put through the call, so you had to dial it yourself, and that could take hours and hours." Relations with Evans were frosty; Joshua had come to live with Ali and Steve and Steve's son, Chad. "It was," says Bergen, "romantic, dramatic, and turbulent. Even the day Ali called to say she was getting married, she was sobbing. I thought, Hmmmm."

The story began to accumulate the retribution of a Victorian sermon against adultery. Once MacGraw had left Evans, she no longer felt she could play Daisy and "have him watch the dailies of me every night," and he felt the same way, so she lost the only part she ever wanted, to Mia Farrow. McQueen made her sign a prenuptial agreement, and she did; then he fooled around. She had increasing guilt about what she had done. "There's another way to have acted out that whole scene. I'd like not to have embarrassed Bob in front of the National Enquirer. I believe, at this point, although I wasn't constantly drinking, that the underpinnings of it were what is now called alcoholic behavior, without the drink.

"I don't want to do adultery anymore. I don't like it, and when it was done to me I felt so zero, so hideous, so unattractive, so rejected, and I transcended it. But the hurt is monumental, and I've done a lot of it. I've been the married woman, and the woman after some married guy. And there's no winning, there's just colossal pain."

When she had been with McQueen for five years, Sue Mengers hauled her to lunch and said, "I don't want you to be one of those actresses who blows her whole career and ends up sitting in a rooming house in Rochester. I want you to have a house." MacGraw was being, in her own word, an asshole. "Convoy. Do it," said Mengers, "because you can't get another job, your marriage is falling apart, and you need to think what you're going to do about money if this marriage ends." Convoy: Peckinpah, Kris Kristofferson. She did it. It came out. In her word: "Thud."

"I think it all stopped when Steve McQueen and I were divorced, and I don't think it ever came back." Her horrible secret, she says, was that she wanted, more than anything, to be "Super In." "I loved the fact that Women's Wear wanted to follow my clothing, loved the fact that people talked about me as someone to imitate, and when it was taken away I felt very hurt. I'm smart enough to know that's real sick, and there is no possibility for tremendous happiness if it's based on being on someone else's list. I don't think I had any idea until recently how hidden that need was; I've been operating for twenty-eight years in worlds where attention is the measure of your success, all the way back to Harper's Bazaar days. Oh, doesn't she have style? By the way, I had none then, but after I started being in costume, and loving it, they said I had style. And when they stopped I got real scared, because I thought, If I don't have that, and I'm not in a hit movie, who am I?"

At the end of her chapter on Diana Vreeland, MacGraw writes: "Years after I had left Bazaar and become a movie star, she seemed to be a bit more interested in me, particularly as I was married to a handsome, powerful, rich man. She even stayed interested through my tabloidsoaked marriage to the Biggest Movie Star in the World. But after that I never heard from her, and it made me sad, because she was someone whose approval I would have liked to have earned, with or without my famous husbands."

Sitting on the couch between the Fortuny pillows, she says, "Walking into one of Sue Mengers's parties post-Steve was to ask the question 'Am I still a woman?' Because Steve in his final years was involved with a lot of people who weren't me." McQueen was already married to his next wife, Barbara Minty, when MacGraw heard indirectly that he had lung cancer; she wrote him a letter that she managed to pull out of the mailbox before the post office could get it. They had no further contact. In 1980 he died.

There followed years of lovers; many of the encounters are described in the book, with real names and names that have been changed "out of respect for people's privacy." In her Betty Ford Center confessional journal, which is bravely published in the book, she writes, "If only I could let go of my compulsive, often sexual need to make up for my own void." We talk about depression. "Do you fall in love when you're really sad?" she asks. I tell her I double my intake of cigarettes and stop bathing; she falls in love. The stories about men, some of which she wrote in anger and some of which she wrote with loving care, do not add up. They are the stiffest part of the book; you feel she is conscious of being watched. The narratives are cleansed of anger and bleached of identifying detail to protect the living, and they have little resonance. Whether this proves that the men were drugs, or simply demonstrates MacGraw's relentless consideration of other people remains a question.

Face-to-face, she's looser and more lucid about sex in general. It's the one area she seems never to have had a problem with, although not having a problem with sex can be a problem in itself. Every man I know considers her, in a man's word, "hot." One who danced with her more than a quarter of a century ago seems not to have recovered from the experience yet. "Sex doesn't fix any lack of communication; maybe the first and second night do, that's got its fresh buzz that gets you through the ignorance, but after the first couple of months, if there's nothing going on... I did a lot of stoned sex because it passed for intimacy, made me feel there was a real connection. But sex doesn't need drugs. Sex is its own narcotic."

In the book the men are a motley crew: Peter Weller, her co-star in the film Just Tell Me What You Want; Mickey Raphael, the harmonica player in Willie Nelson's band; a New Age sage sixteen years her junior; and disguised executives and writers. Those who love her can be funny about her choices. One says, "If Ali walks into a room and Mr. Right is there, and also a trumpet player, she'll head straight for the trumpet player." Candice Bergen talks about her warring instincts: "Half of her drive is towards financial security, but then the other half is to ride off into the sunset with a guy who maybe doesn't have a horse."

Josh Evans once made a scrapbook, much like those she makes for him, detailing her boyfriends; it was not offered for my perusal.

After the divorce from McQueen, she needed to work. "Steve didn't give her any money, of course," snorts a disgruntled and protective Mengers. After Convoy, she made Players, a tennis story produced by Evans, which some industry wags dubbed his revenge on her. She was fiery and good in Just Tell Me What You Want, directed by Sidney Lumet in 1980, but that was the last film she appeared in.

"I know how to. do a lot of things to make a living, and it's a good thing because I've done most of them," she says. After the blow of coming back and, "thud," bombing in two films, despite a good performance in the third, the Lumet, which nevertheless bombed, came the strange alienation of Steve's death. She decorated houses, one for John Calley, the Warner Bros, executive, on an island in the Northeast; a restaurant, the Malibu Adobe. Five years ago, two TV appearances—on The Winds of War and Dynasty—caused a further volley of punishing criticism. "The press invented me and then vilified me," she says, "and neither the cover of Time magazine nor the reviews of The Winds of War are accurate. They're all hyperbole." She cried, privately; in public, she carried on doing the work she had to with what many describe as gallantry. "She never took a penny from either husband!" says one onlooker. Candice Bergen has a lucid description of the reason for her friend's constant financial precariousness: "She is a gypsy, a real one. Part of what's romantic and intriguing about her is that she'd love to have money, but there's a mechanism that makes her divest herself of money, whether it's her incessant generosity, the fact that she pays bills for a lot of people no one knows about, or because, often, on a decorating job, she ends up paying for things herself."

Recently, if you were zapping channels at some lonely hour, you might have come across something between a talk show and a commercial, in which a radiant Ali MacGraw hosts a group of women who are learning about Victoria Jackson Cosmetics. "She makes good cosmetics for people who don't like to wear makeup, like me, and for the last two years that's paid the bills," says MacGraw matter-of-factly. "I've known her for years, and what she makes is wonderful, but I should really be doing Alpo commercials, because I could sell the hell out of dog food."

"Sure, it's disappointing," she answers to the obvious question. "Very. That's the curse, when you start as high as I did. It's time for a little humility. There's a new pack at the top of the heap. It's sometimes devastating, but then you walk down the street in Paris or Vienna or Nairobi, and some strange person says, in broken English, 'You changed my life.' "

Four years ago, in the middle of a bad love affair, a friend persuaded her to check into the Betty Ford Center, which she did under the name Lani Wolff. No one around her had been aware that she had a problem, and many still have trouble accepting it.

"She's always been physically fit, tremendously disciplined, and had the best figure," says Candice Bergen. "It went from that perception to the news that she had come back from the Betty Ford Center. It was as if we'd been given a manuscript with the center pages missing."

"She was a secret drinker," affirms Sue Mengers. "On the surface she was pretty perfect, and then she's very selfdenigrating. But in over twenty-two years I never saw her drunk."

"I've never known her to be an alcoholic," says Evans, "but in her eyes she may have been. I think it was her overall despair at the way her life was going."

In the book, she writes sparsely, almost defiantly, about whiskey, tequila, cocaine. "I was never comfortable with the groups of people," she tells me, "so I used to have a shot of tequila before I went out, and then I'd come home and really get into the tequila. It was periodic. But when it was going on, I'd draw, write poetry, put on the headphones and dance for two or three hours. I'd get into sexual relationships with people I barely knew, very intense; have blackouts."

By the time she said this, we had been talking for several days, and had been to cook our bodies at a local sulfur-spring spa. With all the positive energy coming off her, I had trouble believing that she was an alcoholic, but I felt somewhat wrongheaded in denying her the failing that appeared to be so important for her.

The explanation was simple. It came from Bergen: "Betty Ford helped her relinquish being a movie star. Whatever propelled her to Betty Ford, she is now present in a more realistic way, with greater honesty, but the same gallantry and courage."

"Five years ago," says MacGraw, "I didn't know that nothing fixes that hole in the heart except digging, and finding out who you are. If all the clapping hadn't stopped, I wouldn't have done this work. What for? I'd much rather have somebody rave on about my dress. I haven't worked in five years, but a wonderful thing happens when this life-style I'm living kicks in: I really believe that everything happens in its proper time."

She sent me, before we met to talk, the galleys of her book, in a paper parcel, carefully wrapped, the way they used to be, before the world became disposable. She was brought up using her hands, her head, her imagination, which has only grown, despite the hostile environment of stardom. A friend says that when Josh left her, at sixteen, to live with his father, it was a monumental wrench for her; but she tells the story as a sensible decision on the part of a young man who didn't want to commute for three hours to school every day. Josh, who was central to her life, is now acting in films. "With just me and Bob, in a restaurant on a good night, he'll do us both. He does me charming the waiter relentlessly: 'I love your shirt, how do you do the green beans?' And he does Bob, the speech pattern Bob has, any ah anyah anyahahah, the hyperbole; everything is the biggest and the best. He's Bob. There's somebody who really loves his parents, although they're a little off. Given the dynamics of this family, given that I did the most awful thing that could be done..."

Robert Evans's fortunes have been as shaky in the last years as her career has been dim. His arrest for cocaine possession in 1980 coincided with the disastrous period of the film The Cotton Club and his murky involvement with Lanie Jacobs Greenberger, currently on trial for the murder of Roy Radin, one of the potential investors in the film, a trial in which Evans may be called as a witness. He was also fired as an actor from The Two Jakes, the sequel to Chinatown, one of his greatest triumphs as a producer. He sold his beloved neo-Regency house, where he and MacGraw had lived, only to buy it back immediately for more money. He speaks of her with real affection. "She's too good for the turf. She gives 90 percent and gets back 5 percent. If she'd never left me, both our lives would have been much better. We would have had a stronger focus, and been more accomplished human beings. But that's the shuffle of the cards, and that's the way they fell."

"Do we pay?" asks MacGraw. "We pay. And if we put out good energy, it comes back to us. My conclusion is that if this is it, and this is me—my cats and dogs, and friends, and son, and old lovers, and ex-husband, and gay friends—if that's as good as it gets, that's pretty good. Maybe I've had my helpings."

Not with that face and figure, or that amount of positive feeling. "So it's not the head of the studio, or the biggest star in the world," she says. "So?"

otes on the principal players:

Ali MacGraw's book, Moving Pictures, will be out this month from Bantam.

Sue Mengers, formerly of ICM, then of William Morris, has been reported by Liz Smith to be contemplating her memoirs.

Candice Bergen's autobiography, Knock Wood, was published in 1984.

Robert Evans is working on his life story, to be called The Kid Stays in the Picture.

Josh Evans can be seen in Oliver Stone's latest film, The Doors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now