Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPUBLISH AND PERISH

Was the outrageous Lady Fairfax behind the dynastic crash of Australia's oldest media empire?

BOB COLACELLO

Letter from Sydney

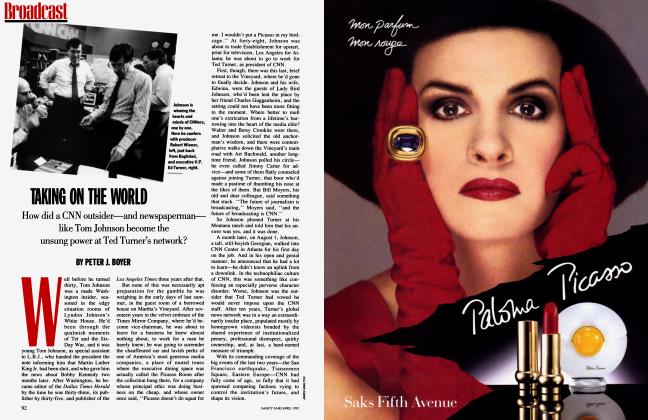

It was not a good year for takeover tycoons. Robert Campeau lost his department stores, Frank Lorenzo lost his airlines, and Donald Trump had to give up half of his Taj Mahal. Things were worse in Australia, perhaps the one country that had embraced the hypercapitalism of the eighties with even greater enthusiasm than America. Down Under, 1990 began with Alan Bond's highly leveraged Van Gogh sailing off to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, and ended with Rupert Murdoch's highly leveraged News Corporation plummeting 20 percent in a single day on the Sydney stock exchange. But the most stunning fall of all was the collapse of the 150-year-old Fairfax publishing empire, which was put into receivership by its banks on December 10—exactly three years and three days after its mysterious young heir apparent, Warwick Fairfax, completed the biggest hostile takeover in Australian business history with $1.8 billion in borrowed money.

John Fairfax Ltd. has been an Australian institution since it was founded by its namesake, a pious printer from Warwickshire, England, in 1841. Its major newspapers, The Sydney Morning Herald, the Melbourne Age, and The Australian Financial Review, are the Australian equivalents of The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, and the Fairfax family has run the company with an admirable commitment to editorial independence for five generations. Because of their near monopoly on quality press in Australia, the newspapers have long been, in the words of the major competitor, Rupert Murdoch, "rivers of gold."

The Fairfax fiasco began with the death of young Warwick's father, the scholarly and monarchical Sir Warwick Fairfax, at age eighty-six, on January 14, 1987. At that time, Sir Warwick's son by his first marriage, James Fairfax, fifty-three, was chairman of the company. Reserved, cultivated, and unmarried, he preferred art collecting and travel to hands-on management, which suited his executives just fine. Once, according to a friend, when the Australian prime minister called him at his country house, James had the butler tell him to call back in an hour, because he was busy gardening.

The deputy chairman was John B. Fairfax, forty-five, son of Sir Warwick's cousin Sir Vincent Fairfax. Athletic, handsome, and practical, John was the only Fairfax to have worked his way up in the company, starting as a crime reporter in 1961. Married and the father of two sons, he took an active role in the Fairfax business.

Sir Warwick's funeral was postponed for two weeks, because James was in Antarctica and young Warwick was studying for his M.B.A. at Harvard. Since the funeral, Australians have watched with amazement, horror, and not a little glee as their "royal family" tore itself apart, with twenty-six-yearold Warwick ousting his half-brother James and his cousin John; as the company sold off its TV, radio, magazine, wire-service, and newsprint assets to Murdoch, Kerry Packer of Consolidated Press Holdings, and other longtime local rivals; as a parade of American financial wizards, including Michael Milken and former treasury secretary William Simon, arranged refinancing after refinancing; and, finally, as a flock of international investors, led by Robert Maxwell and Heinz chairman Dr. Tony O'Reilly, hovered on the long-distance lines, waiting to pick up the pieces, mainly the three illustrious newspapers, which Australians often call "the jewels in the crown." During this same period, backstage deals were also being made within the Fairfax family. Two months before his marriage to Mary, Warwick, on Henderson's advice and ostensibly for tax purposes, sold half his shares to James, on extended payment terms. In fact, it was those shares, when added to Sir Vincent's, that gave James the strength to force his father's hand in the first coup. The day before the coup, Sir Warwick had persuaded James to sign an agreement guaranteeing that those same shares would pass to young Warwick in the event that James, whom the Australian press refers to as a "confirmed

"It's a story of greed and stupidity," says Mark Westfield, The Sydney Morning Herald's financial editor. But intertwined with the business story is an equally compelling family drama about social status, snobbism, and insecurity. And for many its star is neither a bom Fairfax nor a media tycoon, but Sir Warwick's third wife and young Warwick's mother, Lady (Mary) Fairfax.

An extremely controversial woman who has been compared to Catherine de' Medici and the Duchess of Windsor, Lady Fairfax has been portrayed in the Australian press as the driving force behind her son's takeover, and there are those who insist that she's been plotting it ever since her husband was ousted from the chairmanship by James and Sir Vincent in 1976. "She's the Lady Macbeth of Australian publishing," says the Sydney-bom art critic Robert Hughes. "And a creature of staggering pretension."

Others see her as the basically benign "Queen of Sydney Society," who has opened the gates of Fairwater, the Fairfax family estate, again and again for such worthy causes as the Opera Foundation Australia, the Australian Ireland Fund, and the Red Cross, and who has generously entertained glamorous visitors from overseas, including Marc Chagall, Rex Harrison, Rudolf Nureyev, Marietta Tree, and Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau, not to mention Phyllis Diller and Liberace. Sydney's leading columnist, Leo Schofield, told me, "After Paul Hogan, she's possibly the world's best-known Aussie—the Crocodile Dundee of the international social set. All over the world one encounters people whose only knowledge of this country is that Mary lives here."

Two things seem certain: the Fairfax family has never been the same since Warwick senior married Mary Wein Symonds in 1959, eight years before he was knighted. And the family frictions caused by that marriage spilled over into the company right from the beginning.

In some ways, the Fairfax fall can be compared to the Bingham-family feud, which destroyed the Louisville Courier- Journal empire in Kentucky in the mideighties. But that was a relatively simple power struggle among rigid parents and their willful children, and all the players were from the same class and religion. This is the old story of old money marrying new chutzpah—and nobody being happy about it but them.

Because of their distinguished papers, the Fairfax family has long occupied a position that combines the media clout of the Sulzbergers or the Grahams with the social prestige of the Rockefellers. "They're at the center of this little Wasp enclave of old money," one social observer explains. "They all live in the Eastern Suburbs, and most of them are crushing bores. You'll never find a Jew or an Italian at their parties." A member of another old Anglican family, the Horderns, says, "Fairfax boys wouldn't be allowed to marry a 'commoner. ' Even if you were a woman who accomplished quite a bit in business or the professions, you would not be accepted." bachelor," died without producing a male heir. It was dynastic tit for tat, and it hardly boded well for the future of the Fairfax family or their company.

"After Paul Hogan, Mary's possibly the world's best-known Aussiethe Crocodile Dundee of the social set."

Then along came Mary, who not only was from a Jewish family that had emigrated from Poland in the twenties, but also had a degree in pharmacy from the University of Sydney and was the owner of a successful chain of dress shops in the Western Suburbs. To complicate matters further, both she and Warwick were married when they met, in 1957, at a dinner dance at the Danish consul general's, which they attended with their respective spouses.

Warwick, then in his fifties, was married to his second wife, a Danish heiress named Hanne Bendixson, and they had a young daughter, Annalise Fairfax. He also had two grown children, James and Caroline Fairfax Simpson, from his first marriage, to Marcie Elizabeth Wilson, who was from a proper Eastern Suburbs family. The future Lady Fairfax, then thirty-five, was married to Cedric Symonds, a leading divorce lawyer, and they had a seven-year-old boy named Garth.

Within eighteen months both couples were divorced in a blaze of headlines, and Cedric Symonds, alleging that Warwick Fairfax had "induced" his wife to leave him, slapped Fairfax with a $224,000 lawsuit, making the double-divorce scandal even bigger. Warwick married Mary Symonds on July 4, 1959, shortly after midnight and at home, to avoid the press. On December 2, 1960, after an exceptionally difficult pregnancy, she gave birth to their son Warwick—"the Dauphin," as Robert Hughes calls him.

But the lawsuit and the headlines raged on. Finally, in January 1961, the powerful managing director of John Fairfax Ltd., R. A. G. Henderson, supported by James and Sir Vincent, asked Warwick to step down as chairman until the embarrassing lawsuit was settled. Two months later, in a secret out-of-court deal, it was, and Warwick was reinstated. This incident is known as "the first boardroom coup"— the second being the 1976 ousting of Sir Warwick.

"Mistrust and suspicion didn't occur in the family until Mary appeared on the scene," Caroline's husband, Philip Simpson, told me. "I knew what she was up to from the first," Caroline said, "and you didn't need an M.B.A. from Harvard to figure it out." Her husband added, "And it had absolutely nothing to do with her being Jewish or Catholic or a refugee or anything."

"What disturbed us," John B. Fairfax told me, "was her life-style. Her extravagance, her publicity-seeking, her social-butterfly stuff, going around in RollsRoyces, wanting to be seen... was certainly opposite of the way we lived."

According to John, his parents, Sir Vincent and Lady Nancy, who live next door to Fairwater, always drove their own Rovers or Saabs.

James Fairfax told me,

"There was a tradition that the Fairfax family was not mentioned in the Fairfax papers, unless they made news. That could be a birth, a death, a divorce, or going to jail. Well, that was a tradition she endeavored to have broken. I think she prevailed upon my father on occasion. But it was a kind of running battle between her and the management, backed by me, to try and keep the tradition enforced. The only objection my cousins and I had was when ^he interfered in office matters. Outside the office, we tried to be friendly. She and my father came to dinner quite often, and I went to Fairwater from time to time. But she had an awful lot of dinner parties."

"Mary would think nothing of having eight or nine major, black-tie dinner parties a month," says Primrose Potter, who grew up with the younger Fairfax children. "For everyone from Ann Getty to the mayor of Camden Town. She has great pizzazz. She loves life, she loves people, and she loves entertaining. What's wrong with that?"

"There's nothing evil about Mary," says another old family friend. "She made Sir Warwick very happy. It's just that she's an ambitious woman. I suppose they're two a penny in New York, but here she sort of stuck out."

Sydney had never seen parties like Lady Fairfax's, which featured everything from after-dinner opera recitals to ice kangaroos with caviar in their pouches. For a Freedom from Hunger Campaign fund-raiser, she staged a poolside fashion show for dogs. The invitation to a 1983 bash for the Australian Opera Trust Fund, at which the guest of honor was Chariots of Fire producer David Puttnam, asked guests to "Bring Your Own Candelabra." But she made her biggest splash in 1973, with the party she gave the night after the inauguration of the Sydney Opera House, inviting all the glamorous guests who'd flown in for that event, including the Queen of England. Elizabeth II didn't attend, but Imelda Marcos did, and the band struck up "Ho, Ro My Nut Brown Maiden" as she entered.

During that same week, Sir Warwick and Lady Fairfax christened their two adopted children, Charles and Anna, with godparents including the Duke and Duchess of Bedford, Christina Ford, Sao Schlumberger, and Viscountess "Bubbles" Rothermere, all of whom were in town for the opera-house festivities. The children had been adopted as infants in England in 1968, because Lady Fairfax had suffered five miscarriages after Warwick's birth and he wanted a brother and a sister.

"Mary adored young Warwick," Primrose Potter says. "Her eyes would light up when he came into the room. He was the whole center of her world. Actually, she was terribly generous with children—with her time, I mean. She'd pick us all up from school and take us to afternoon tea at Prince's, the chic restaurant."

She also desperately missed her other natural-bom son, Garth, for whom she had fought a drawn-out custody battle with Cedric Symonds. He finally won full custody in 1962, and she didn't see her child again for twelve years. "When Garth was being Bar Mitzvahed," a friend recalls, "Mary sent the chauffeur over to our place with a beautiful set of Encyclopaedia Britannicas for us to give him in our name."

The same chauffeur drove young Warwick to the exclusive Cranbrook School, which is directly across the road from Fairwater. "He was dropped in the Rolls every day," says Yves Hernot de Coatmenec, who taught art and art history there from 1975 to 1977, when Warwick was in his teens. "He was bullied by the other kids. He was very shy, very introverted, a loner, not even friendly with another loner, purely on his own. I thought he was highly intelligent, and he was always very polite, very proper. But I never had a real conversation with him in six terms. He seemed withdrawn. He never smiled."

Primrose Potter saw a different side at home. "I remember as a little boy he loved table tennis, and he was determined that he was going to be the best at it and damn nearly won every game— against me, against his mother, his father, or whomever else was playing."

Every year, Lady Fairfax had a photographer from The Sydney Morning Herald come to Fairwater to take a picture of the three children for her Christmas card, an eight-page production filled with quotations from her readings that year and her own poetry. One year, when Warwick was about eleven, he was photographed in a purple velvet jacket and short pants sitting in a tree, playing a fiddle, with little Charles and Anna looking up at him. After that, he was known around the office as "Little Lord Fauntleroy. ' '

"We always felt sorry for him," his cousin John said. "There was always this tremendous push on the part of his father and mother to tell him that it was his destiny to run the John Fairfax company. We never had any difficulty with that, providing, of course, that he was capable of that."

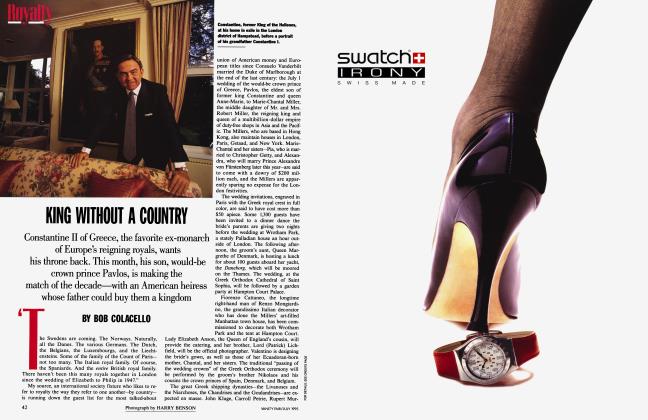

Six days after the once mighty Fairfax empire was taken over by its banks, I interviewed Lady Fairfax at Fairwater, a stolid Victorian mansion of sandstone and brick. A butler greeted me in the front hall, which is dominated by a larger-than-life Rodin male nude, and led me to the sitting room, where Lady Fairfax was waiting. A small woman with a big head topped by a Nancy Reagan hairdo, she was wearing a simple Valentino dress. All around her, on every tabletop, were framed photographs of her with famous friends, including five with President and/or Mrs. Reagan. Behind her, through French doors, I could see the five-acre garden rolling down to Seven Shillings Beach and, beyond that, across the harbor, the Sydney skyline.

It was a sweltering Sunday afternoon, and the weekend papers were full of hard-hitting HEADLINES-MUMMY DEAREST and MARY HAD A LITTLE PLAN. Lady Fairfax was showing the strain, but she didn't budge an inch from her version of the takeover or the family history behind it. She repeatedly emphasized two points, both contrary to much of what had been reported in Australia: She never encouraged young Warwick to take over the company. She always believed in the unity of the Fairfax family.

To begin with, she said, she didn't have a problem with the family because of her different background. "In fact, my background was pretty similar. My family had wealth a great deal longer. My father went to a military academy in Russia with relatives of the czar. His family had breweries and real estate in Warsaw. But the main money came from the wheat contracts with the Russian army, and it was from many, many generations." Her family was "agnostic," she told me. "If I had been brought up in Judaism, it wouldn't have worried me what people think. I've never craved acceptance by anyone."

She was not an ambitious woman, she said, and her role model as a young woman had been Madame Curie, not Machiavelli, as the press was suggesting. "Ambitions are O.K. for other people. I think the thing that I'm best at is looking after a man. And I love children. But I don't believe in smother love. I had no dynastic feelings for our side of the family. I'd have been just as happy to have a girl. As a family we were so close. We shared similar goals. People who say otherwise must be reading too many Greek tragedies. I've never felt revenge, because it does harm to your health. And I find it difficult to get really angry. If someone acts badly, I will get a feeling of distaste."

Wasn't she angry when her husband was forced out of the chairmanship in 1976? "Sir Warwick was much more angry than I was. He was so angry he slammed a door off its hinges. Because he wanted to be there until he died, like his father was."

"Warwick looked like the Prince of the Nerdsfunny shoes, trousers at half-mast, carrying his present in a plastic bag."

"Dad really had to go," Caroline Fairfax Simpson told me. "Her interferences were insupportable. She was quite cunning. She'd call the paper on a Sunday night and get some assistant editor to put in an announcement of a Fairwater event." According to Caroline, the break was bitter. "It was made clear to us that we wouldn't be welcome at Christmas Day dinner in '76—and in '77, '78, and '79. We went next door to Sir Vincent's those four years—we were rescued. And then, out of the blue, she rang Philip up and wanted him to arrange young Warwick's membership in the Royal Sydney Golf Club." James Fairfax confirmed this. "Neither my father nor Mary spoke to me for four years."

Lady Fairfax insisted that no Fairfax was to blame in either the 1976 overthrow or the 1987 takeover: "Sir Warwick never thought for a moment that James did it. As James never thought for a moment that young Warwick did it. James thinks I did it." She then told me, "It's almost like a Wagnerian leitmotif: Sir Warwick trusted a man named Henderson. James trusted a man named Gardiner [the company's general manager in the eighties]. And Warwick trusted a man named Dougherty."

Martin Dougherty, a former Murdoch journalist and editor, was working for an international public-relations company when he met Lady Fairfax in 1982. He soon set up his own firm, with clients including Murdoch, Kerry Packer, Donald Trump, and Sir Warwick and Lady Fairfax, who told me that his work for them was limited to development plans they had for their two-thousand-acre country property, Harrington Park, in Camden Town, near Sydney. "Mary and Marty became bosom buddies," says Jeanne Pratt, the Melbourne art collector who introduced them. Other sources say Dougherty soon became a fixture at Fairwater parties.

' ' He was no closer to me than 150 other people," Lady Fairfax said. "But I try to touch every life with good, and when I heard he was starting his own business, I took him in, introduced him to people, and got his wife on a social committee. What I didn't know was that he was seeing young Warwick."

In his best-selling book on the Fairfax saga, The Man Who Couldn't Wait: Warwick Fairfax's Folly and the Bankers Who Backed Him, V. J. Carroll suggests that Lady Fairfax and Rupert Murdoch were "potential" allies, and that Martin Dougherty was a kind of gobetween. "As a retained adviser, he had kept in touch with Murdoch," Carroll writes, "and kept Murdoch in touch with Fairfax affairs." Lady Fairfax said it was "only speculation" to point a finger at Rupert Murdoch, whose single public comment on young Warwick's takeover has been endlessly quoted in the Australian press: "I wish I'd had the guts to do the same thing when I was twenty-six."

Dougherty became young Warwick's closest adviser during the takeover battle, and was made a board member and editorial director after the takeover. Most close observers find it hard to believe that Lady Fairfax had no knowledge of her son's contacts with him. One regular guest at her dinner parties says, "The walls at Fairwater are not as soundproof as Mary likes to think. She'd pull Dougherty into the next room and they'd get Warwick on the phone and Mary would be hovering over Marty telling him what to tell Warwick."

Young Warwick had been away from Australia since 1979, when he left for Oxford. After graduating in 1982, he briefly worked at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency in New York and then for three years at Chase Manhattan Bank, in a division specializing in takeover financing for media and entertainment companies. In 1985 he started at Harvard Business School. Though he reportedly admired the economic policies of Thatcher and Reagan, he was definitely not a yuppie. According to friends, he always wore the same "tatty jacket," and his watch was a Seiko, not a Rolex.

At Oxford he had become involved with a nondenominational, international Christian fellowship which has no official name, leaders, or members. Its "supporters," as they like to be called, say that it is neither fundamentalist nor New Age. Prominent American supporters reportedly include Senator Mark Hatfield and the secretary of state's wife, Susan Baker.

When Warwick returned to Australia, in May 1987, he shared a house with three other young men from the fellowship in Neutral Bay, in the middle-class Northern Suburbs. He bought a secondhand car and reportedly spent his weekends helping friends from the fellowship renovate their houses or bushwalking.

A Fairfax-family friend recalls a rare appearance young Warwick made on the Eastern Suburbs social circuit, at Kerry Packer's daughter's twenty-first-birthday party, in August 1987: "He looked like the Prince of the Nerds—funny shoes, trousers at half-mast, carrying his present in a plastic bag. He's not at all socially adroit. He's deliberately antisocial."

When asked why he had moved so far away from Fairwater, Warwick was said to have replied, "If you had a mother who gave dinner parties for thirty every second night, you'd move far away, too."

Warwick Fairfax is often compared to Howard Hughes, in his Mormon phase, because he has never given an interview. He did not break his vow of silence for this article. Martin Dougherty was also unavailable. But the business relationship between these two key players has been well documented. As with everything else in this story, there are several versions.

Everyone agrees that they had their first business discussion at the Pancakes on the Beach restaurant in Bondi in December 1986, when young Warwick was home for Christmas vacation and old Warwick was close to death. Everyone also agrees that young Warwick expressed his disapproval of the way the company was being run by James, John, and Greg Gardiner, the general manager. He was particularly critical of what he saw as their lackluster performance in the epic takeover battle for the Herald & Weekly Times media group the previous year, in which Fairfax was outsmarted by Murdoch and the late Robert Holmes a Court, Australia's fiercest corporate raider in the eighties.

That's where the agreeing stops. In a court case that grew out of the takeover, Warwick testified that Dougherty had suggested he take over the company. Dougherty said that it was Warwick's idea and that it grew naturally out of the discussions that had been going on at Fairwater since 1984.

"I will never forgive Mary or Warwick. It's for more important than our lives. It's important for Australia."

According to Lady Fairfax, one month after Sir Warwick's death, after Dougherty called her son at Harvard and discussed the possibility of Holmes a Court raiding the company, Warwick took the first fatal step in what would become the takeover process, which was to bring the whole family's holding up from a total of 48.6 percent of the stock to more than 50 percent. At that point, Sir Vincent and John held 14.5 percent; James held 17.1 percent; Lady Fairfax and young Warwick jointly held 11.3 percent; Lady Fairfax alone held another 1.1 percent; and other family members held 4.7 percent. Both Holmes a Court and Packer had been buying shares since Sir Warwick's death, as had Sir Peter Abeles, a Murdoch ally, but it wasn't clear whether those were serious threats or just greenmail tactics.

Warwick called James and John and asked them to buy an additional 1.5 percent with him, splitting the $24 million cost three ways. James said no, because he didn't think the danger was real. John said he'd take a sixth of the new shares, but only if his losses were guaranteed, which Warwick refused. Warwick then called his mother and asked her to borrow the $24 million with him. "If I had been pushing for the takeover," Lady Fairfax said, "why wouldn't he have asked me first?"

Why did she go along? "Warwick is like his father, so determined. And he had never asked me for anything. He never asked me for money, or for cars. It was so out of character. But after a lot of pressure, I agreed. It was the most foolish thing I ever did. If I had said no, nothing could have happened."

On February 17, 1987, Lady Fairfax and young Warwick bought the extra shares and took on an annual interest bill of about $5 million, more than double their estimated income from dividends. In a sense, no matter whose idea the takeover was, they were trapped. They had to find some way to get more money out of the company, and a takeover would accomplish that. They sought advice from the Baring Brothers Halkerstone bank, which advised against proceeding. Then, in April, Martin Dougherty found Warwick a banker who said it could be done, Laurie Connell.

"Last Resort Laurie," as he was nicknamed, was a high-flying financier from Perth, who was then in the midst of building a $14 million palace inspired by the Alhambra for himself—seven mansions had been tom down to make way for it. Connell and his associate, Bert Reuter, put together a secret plan to take over John Fairfax Ltd. It was called "Operation Dynasty," and in it young Warwick was referred to as "the Heir." They were to receive an unheard-of $72 million fee for their efforts, with 10 percent of that going to Dougherty.

Lady Fairfax said that Warwick had always intended that James and John be part of the takeover. Laurie Connell has said he knew they'd never go along with it. They certainly weren't given much time to make up their minds. On Sunday night, August 30, 1987, Warwick went to^see first James and then John and told them about the takeover bid he was making the next morning on the Sydney stock exchange.

"Stupidly, I was surprised," John Fairfax told me. "Warwick and I had had a fairly long talk that Christmas, and I thought some of his ideas were actually quite sound." John said he told Warwick then that James had promised him the chairmanship when he stepped down as planned in 1991, and that he was prepared to turn it over to Warwick ten years after that, when Warwick would be only forty-one.

"The man who couldn't wait says it all," Caroline said. "Warwick didn't ask them before, because he knew damn well they'd say, 'Don't be a fool.' "

Lady Fairfax said that she was not privy to the late-night strategy, because she was at the Salzburg Festival that August. A fellow festivalgoer told me, "Every other call she made was to Martin Dougherty."

In September, after getting Warwick to raise his bid a dollar a share, the family gave in and sold out. James got $116 million, and has since added a $3.5 million Antonio Guardi to his collection of European paintings, which includes a Tiepolo, a Canaletto, and an Ingres. Another $218 million went to Sir Vincent and John, who used a large part of it to buy suburban and rural newspapers that had been part of the Fairfax group. Caroline and Philip Simpson said they also received "a substantial sum."

In October the stock market crashed, and Lady Fairfax tried to call the whole thing off. In a scene that has assumed legendary proportions in Australia, she went to the Regent Hotel, where Warwick was meeting with Dougherty and Reuter in a penthouse suite, to try to persuade her son to stop the deal. Warwick wouldn't see her, and tossed the note she sent up into the wastebasket.

"She didn't try very hard to stop it," Caroline told me. "Sending up a letter! Why not just go up there? He was her son, after all." David Marr, who has produced an Australian TV documentary on the Fairfax story, says, "Mary backed him, until the crash. But at that point this tremendous Fairfax stubbornness in the boy defeated his mother's commercial shrewdness."

After the crash, Warwick had to pay a high price for his mother's cooperation. In October 1987, they signed an agreement by which she received $2.6 million outright; a guaranteed annual income of $1.9 million for life, tax-free and indexed for inflation; the Grand Hotels in downtown Sydney and Harrington Park, both unencumbered by mortgages; and an option to sell her personal 1.1 percent of the company for $24 million, which she exercised a year later. In March 1988, it was agreed that she would receive 25 percent of the new company for the rest of her shares in the old company. And in October 1988, after an all-night legal session with Warwick and his lawyers, she came out with a guarantee that if the company was liquidated she would receive the first $122 million after the creditors.

About the same time, Lady Fairfax purchased the top two floors of the Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, including a 110-foot-long ballroom, for $12 million and announced that she was planning to spend several million more restoring it to its former splendor. According to her decorator, Frank Grill of Sydney, there will be an apartment within the apartment, which Lady Fairfax plans to rent to cover the annual $250,000 maintenance. All together, there will be six bedrooms, seven bathrooms, and four kitchens, including a commercial-size kitchen, where, Lady Fairfax said, "you could roast half an ox."

The secret plan to take over John Fairfax Ltd. was called "Operation Dynasty." Warwick was referred to as "the Heir."

Meanwhile, back at the John Fairfax company, everything was falling apart. After the crash, planned asset sales either fell through or were greatly discounted because some of the buyers went bankrupt and the assets themselves were now worth less. Laurie Connell's bank also went bust, and his fee was assigned to Alan Bond, who sued Warwick to collect it; the lurid 1988 trial was another embarrassment for the Fairfax family. Warwick fired Dougherty and hired Peter King, whom he had met through the fellowship and who had no experience whatsoever in publishing, to run the company. Goldman, Sachs and Lazard Freres and William Simon were all called in to offer advice, the last lured by Lady Fairfax herself. He lasted on the board for a month, long enough to bring in Michael Milken and Drexel Burnham Lambert, defunct now too, which peddled $450 million in junk bonds, mostly to Americans, including the Bass brothers of Texas. When the company was put into receivership last December, these bondholders were left out in the cold, and are considering suing the banks that now control the company—the Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, which is owed about $421 million; Citibank, which is owed about $345 million; and two smaller banks, which are owed about $77 million.

Through it all, the new proprietor, young Warwick, maintained a weird silence. "I've seen him sit at board lunches for an hour and a half, with six or seven people whom he knew very well, and not say one word," says Michael Smyth, a banker who worked with Warwick for eight months in 1990. "It's difficult to tell if that's because he doesn't have an answer or is being canny."

I had heard rumors that Lady Fairfax had considered suing her son in 1990, and that was later confirmed by both Fairfax executives and her current public-relations adviser, Murray Williams. "I have never brought any case against anybody in my family," she told me. "How could I do that? I accept him how he is. I love him. I love my four children." What did she think would happen to the company now? "I wish I knew. I'm only glad that my husband isn't alive to see it. And my heart is broken, because that poor boy Warwick did everything right, until Dougherty came into his life."

"I regard Warwick's action in making the takeover bid as the reason for what happened to the company, including the receivership," said James Fairfax, whose memoirs will be published in September. "His mother has denied revenge as a motive. I go into that in the book."

"Any attempt at family unity is futile now," said John Fairfax, who would neither confirm nor deny that he was trying to buy The Sydney Morning Herald. "You can't make people like each other."

"Does Mary realize the enormity of what she and her son have done?" asked Caroline Fairfax Simpson. "I will never forgive her or Warwick. We're angry because it's something far more important than our lives—we're here today, gone tomorrow. The point is, it's a great publishing company and it must be bought by someone who respects journalistic integrity. It's important for Australia."

In May 1989, Warwick married Gale Murphy, an American girl he met through the fellowship. They are reportedly expecting a baby. They live in Chatswood in the Northern Suburbs, in a small red brick house with a red tile roof—plain, average, and anonymous. The day the receivership was announced, Warwick was caught by a photographer at the front door, and his picture ran on the front page of The Sydney Morning Herald. He was smiling. "I think Warwick got what he really wanted in the end," a family friend told me. "You could see it from the look in his eyes in that photograph. He was finally free."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now