Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowUnder the Gun

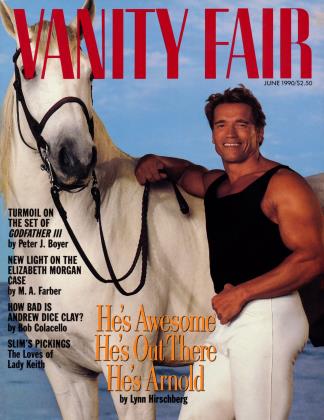

Paramount has $50 million riding on The Godfather. Part III. For Francis Ford Coppola, racked by self-doubt over the collapse of his Zoetrope Studios and still grief-stricken by the death of his son, the stakes are infinitely higher. But amid endless rewrites, on-set dramas, and spiraling budgets, Coppola is working his losses into a vision—maybe even a masterpiece. PETER J. BOYER reports from Sicily

At the foot of the steps of the Villa Malfitano in Palermo sits a squat aluminum motor home, one of those shiny Airstream jobs that look like giant silver pill bugs on wheels. The door is closed, and the curtains are drawn. Wires and cables and power lines disappear into its underside and various orifices. A generator hums.

Inside that customized Airstream, outfitted with a leather couch, a miniature gourmet kitchen, an espresso machine, and a Jacuzzi, Francis Ford Coppola is making The Godfather, Part III. Along with the aforementioned comfort options, the Airstream, which Coppola calls "Silverfish," is equipped with two walls full of monitors, computers, and state-of-the-art video-editing equipment—the tools of Coppola's so-called electronic cinema. Like a bearded, corpulent Oz, Coppola pulls the levers of Godfather III from behind the curtains of that trailer, usually emerging for lunch and for the actual take of a scene, but sometimes not even then. He holes up for endless hours, directing, editing, cooking, and, most of all, writing and rewriting the script. He has written so many versions of Godfather III that people on the production team don't bother to count them anymore. "With Francis, a script is like a newspaper," says production designer Dean Tavoularis, a longtime Coppola collaborator. "You get a new one every day."

All of this gives the production of Godfather III a certain anxious air, but many of those who have long known and worked with Coppola, who are accustomed to the Silverfish and the director's bouts of on-the-spot rewriting, note a particular edginess to this production. "It is different," says Tavoularis. "I don't know why it is, I can't really explain it, but it's different. It's more difficult."

"Difficult" understates it. The production has experienced the banishment from the set by Coppola of two loyal producers, a lovers' rift between the two leading actors, the nervous collapse of another featured actress, an on-set revolt over a controversial Coppola casting decision, and a confrontation with Paramount Pictures, the studio that is financing the film. The project is $6 million over budget, several weeks behind schedule, and its original Thanksgiving release date has been delayed until Christmas. The tension has been magnified by the near-claustrophobic effect of a strict order of secrecy on the production, which has included the numbering and shredding of scripts to keep details of the story from leaking.

In that Silverfish with Coppola, of course, is $50 million worth of Paramount Pictures' dreams, a gamble so huge it can be explained only by the powerful hold that the Godfather saga has on the Paramount culture.

There was one more crisis before the production left Rome: a lovers'quarrel between Pacino and Keaton.

The Corleone saga presents Paramount executives with an exquisite quandary. On the one hand, it is an irresistible franchise, embodying the two principal (and seldom complementary) motivations of the movie business: the urge to make money and the urge to make art. The Godfather, planned as a cheap gangster movie, was transformed by the young Coppola into an epochal achievement, breaking the Gone with the Wind and Sound of Music box-office records and winning the Best Picture Oscar for 1972. Godfather II, two years later, surpassed the original artistically and swept the major Oscars, including Best Picture. Together, the films eventually earned $800 million in revenues. Paramount executives have been so desperate to go to the Godfather well again that two of them, the late Gulf + Western founder, Charles Bluhdom, and former Paramount production chief Michael Eisner, even tried to write a third Godfather story themselves.

On the other hand, the one man who could make Godfather III was Francis Coppola. "It had to be Francis," says current Paramount chairman Frank Mancuso. "It always had to be Francis." Which leaves Paramount crossing its corporate fingers and entrusting its $50 million baby to the man who spent the years since Godfather II earning a reputation as an epic wastrel—and one who'd lost his touch, at that.

Remarkable as Paramount's risk is, there's even more at stake for Coppola himself. Debts and legal battles lingering from the production of his disastrous $27 million techno-musical, One from the Heart, have come back to haunt him in the form of a court judgment ordering him to repay an old $3 million loan, which, with interest and fees, has swelled to $8 million. Coppola had to file for Chapter 11 protection, and he worries about losing his beloved vineyards in the Napa Valley. He is receiving $5 million for directing, cowriting (with Mario Puzo), and producing Godfather III, but he also owns a percentage of the gross, which could bring him millions more. "If Godfather III is a big financial success, it will enable Francis once and for all to end the financial problems that were created by One from the Heart," says Fred Fuchs, president of Coppola's San Franciscobased production company, Zoetrope Studios.

And if not? "I'm back to the poverty level," Coppola says.

Professionally, Coppola, at fifty-one, is trying to find his way back from selfdoubt and a long, long box-office drought. After the One from the Heart debacle in 1982, Coppola was forced to break his vow to make only personal films, and he became a director for hire on such commercial disappointments as Peggy Sue Got Married and Tucker: The Man and His Dream. By the end of the eighties, he was widely regarded as a has-been.

"When I ran into the brick wall. . .it became the popular thing to do to disavow me," Coppola says. "What it really did was it shut off the faucet of resources that came to me."

Godfather III may be Coppola's last chance to regain his standing as one of the masters of the movies, and the studio backing that comes with it. "He's on the line with this project," Tavoularis says as he considers the man inside the Silverfish. "He's got to make it good. It can't not be good. It's gotta be good. But there's no law that says it's going to be good. And that's the stress factor. ' '

Once, when Coppola was a little boy, his mother disappeared for two days after an argument with Francis's father. When she returned, she told Francis that she'd spent the two days alone, in a motel. The thought of it struck the boy, and stayed with him, and when he became a filmmaker he decided to make a movie about a young married woman trying to run away from her responsibilities.

It was 1968, and Coppola had a wellpaying studio job as a screenwriter, but he yearned to break free of Hollywood's constraints. He talked his studio, Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, into putting up $750,000 for the film he would call The Rain People. He put together a unit of twenty people that included his college pal James Caan and another future Coppola standby, Robert Duvall, with a young George Lucas serving as cameraman and technician. Coppola had his idea—a pregnant woman (played by Shirley Knight) leaves her husband and takes to the road—but a loose script; he and his crew would caravan from New York to wherever their instincts took them (Nebraska, as it happened), and Coppola would shape the script to fit their experience.

One hundred and five days later, he had his movie, a dark little film that attraded some kind notices, if not much commerce. More important, Coppola had found his purpose, and his style— he would make art, not just movies, and the inchoate hints of intuition would be all the blueprint he would require. It is the sort of sentiment that young cineasts are prone to, but unlike most other young filmmakers, Coppola never outgrew it, even after achieving commercial success. "You just have to make something beautiful," he would say. "You can't worry about if anybody will see it."

Coppola's make-it-as-you-go approach is highly unusual, but then, he has always had a near-religious devotion to unorthodoxy. "There is disagreement between the way things are and the way I think things should be," he once grandly put it. His vision can be a method for making art, but it can also be called chaos, and it can be a formula for disaster, as Coppola demonstrated with his Vietnam epic, Apocalypse Now. He went to the Philippines in early 1976 with a budget of $12 million, a shooting schedule of five months, a vague creative commitment to John Milius's script, and no ending in mind for the film. He emerged with a finished movie three years and $30.5 million later. Along the way, he'd suffered an emotional breakdown, nearly wrecked his marriage, and established a reputation for recklessness that his failures of the eighties cemented.

Paramount kept approaching him about taking up the Corleone saga again, but Coppola wasn't interested in any of the scripts the studio had commissioned—spin-off yarns, mostly, which quickly shed the original characters and drifted into plots about drug cartels and assassinations of LatinAmerican dictators. "I always hated the scripts they had," Coppola says. "It made me think they don't have a hint of really what it is. For one thing, to talk about making subsequent Godfather movies and not even have any idea that you should build it around some of the great actors, Al, Bobby De Niro—none of them. . . . They all seem to want to take the Godfather characters and just hook 'em onto another movie."

In one last effort to entice Coppola, Mancuso sent the director a script written by Mario Puzo and reworked by Nicholas Gage. To make sure Coppola got it and read it, Mancuso asked Coppola's sister, Talia Shire, and her husband, producer Jack Schwartzman, who planned a visit to Napa, to deliver it personally. Coppola read a bit of the script and was so annoyed by it that he threw it in the fireplace. But it got him thinking. "It was sort of reading the script they gave me, Nick Gage's script, that made me pause to reflect and say, Well, if I was going to make it, what kind of movie would I want this to be?"

When Coppola told Frank Mancuso what he would do with Godfather III, his suggestions were so specific and so contrary to any of the scripts Paramount had, it was clear that if he were to direct, it would have to be his own script. What would it take to get him to say yes? Coppola told the studio chief that he wanted what Paramount had given him for Godfather II—complete artistic control. "Support me and let me try to do my best to go do my own thing," Coppola said. But he'd been given that earlier deal when he was golden; now he was damaged goods. Perhaps sensing some reservation, Coppola added, "I can assure you, my own thing will be something coherent, and hopefully exciting; it's not going to be like an experimental movie all of a sudden." Mancuso agreed to his terms.

By Hollywood standards, it was an act of extreme courage for Mancuso to insist upon and hire Coppola. After a long run as the box-office king of Hollywood studios, Paramount has slipped in recent years and is struggling to regain its pre-eminence. The faceless jury of collective wisdom that adjudicates the movie business would be much more forgiving of an inexpensive Godfather knockoff that flopped than it would be of a $50 million Coppola failure.

The Paramount chairman, however, was not prepared to give Coppola a blank check. The studio wanted more than intuition as a blueprint for this movie, and so it gave Coppola $50,000 to devise a feasibility study, which was really an exercise designed to get the director to come up with an honest-togoodness plan for the film. "There literally was an entire calendar that was part of this feasibility study," Mancuso recalls. "It had an enormous amount of detail, with specific goal-oriented guidelines in it." Some close to the production say that the plan even inspired incentives in Coppola's deal, tying his potential take from the film to a rigid delivery schedule.

After ten years in directors' hell, Coppola was now panicked that Godfather III was spinning out of control.

Even if it came in on schedule, Godfather III would be a very costly movie. Coppola and Mancuso agreed that it needed as many of the original participants, in front of and behind the cameras, as possible, and they had become a high-priced group. Pacino is said to be getting $5 million to reprise his role as Michael Corleone, the bloodless don, and Diane Keaton commanded $2 million to come back as Michael's estranged wife, Kay. Robert Duvall wanted nearly as much as Pacino was getting to return as the consigliere, Tom Hagen, but Paramount balked, and he was written out of the story. Even so, the above-the-line cost of the movie—the amount paid to the people, as opposed to production costs—reached $20 million, making the picture's overall production budget of $44 million reasonably tight.

His deal in place, Coppola went to work with Puzo on the script. They rented a suite at the Peppermill Hotel Casino in Reno, and Coppola laid out his story on index cards, which he pinned to a bulletin board. In preparation, he'd immersed himself in Shakespeare, taking inspiration from King Lear, Titus Andronicus, and Romeo and Juliet. He envisioned Godfather III as a classic tragedy, simpler in its structure than the complex father-son antiphony of Godfather II.

The central character would again be Michael Corleone, the reluctant but natural gangster, still yearning for legitimacy. Rejected by his own son, who repudiates the bloody Corleone legacy to become an opera singer, Michael finds a surrogate in his nephew Vincent Mancini, Sonny Corleone's bastard son, who, like Edmund in Lear, lusts for the kingdom that his lack of a birthright has denied him. The story, which Coppola and Puzo want to call The Godfather, Part III (The Death of Michael Corleone), means to resolve the tragedy of the Michael Corleone character without terminating the saga itself.

For the first time, the ultramasculine Godfather story would have a strong central female character, Michael's daughter, Mary, a thoroughly Americanized young woman with a Seven Sisters education and a determined will— demonstrated by her forbidden romance with her cousin Vinnie. Coppola had wanted Julia Roberts for the role, but she was booked solid. Madonna let it be known that she was interested in the part, in any part in the film, and Coppola invited her to Napa for a test; George Lucas, who wanted to meet her, wangled a dinner invitation. "She was fabulous," Coppola says. "We all fell in love with her." At the time, Coppola was considering Robert De Niro for the role of Vincent, but when he decided that De Niro was too old for the part, he had to cast a younger actress as Mary too, and he chose Winona Ryder. For a time, Madonna was also being considered for the role of Grace Madison, a power-loving international photojoumalist who is drawn to Michael Corleone, but that part went to Bridget Fonda.

The one area where Mancuso and Coppola strongly disagreed was the matter of a timetable. Coppola wanted to spend eight months on the script alone, and deliver the film for a 1991 release. Mancuso insisted that the movie be in theaters by Thanksgiving 1990, giving Coppola less than twenty months to write, direct, and edit the movie. The stress factor ratcheted up another notch.

A s shooting began in Rome late last year, Coppola and -£l_Paramount were still arguing about casting. Coppola wanted George Hamilton in the role of Michael Corleone's slick adviser, but Paramount president Sidney Ganis and Gary Lucchesi, the studio's production chief, feared that Hamilton's lightweight persona didn't fit the movie. "What you are initially afraid of is that George Hamilton has a notoriety for comedy" is how Lucchesi diplomatically characterizes the disagreement. "The press makes fun of his suntan a lot" is how Ganis puts it. Coppola finally convinced Ganis by drawing on the image of a Hollywood archetype. "Sidney, do you know what kind of a lawyer I want in this role? Think of Greg Bautzer," Ganis recalls Coppola telling him. "And I said, 'Got it, let's go.' "

Shortly thereafter, Coppola and Ganis were walking along the Campo dei Fiori, in Rome's bohemian section, where Coppola kept an apartment, and the director joked, "Don't worry, Sidney, this is only Crisis No. 2. There'll be at least seven of them before we're through."

Coppola could be glib with Ganis, but, in truth, the strain of the tight schedule and budget was beginning to show. He was gaining weight, and losing his humor. He was less gregarious than usual; there were fewer dinners and parties. "It's so draining, just in energy and time, that it curtails him," one associate says.

One morning during the first week of production, Coppola arrived at the Vatican with his film crew to shoot a scene in which Michael and his associates pass through the Vatican gates. But the Swiss Guards refused to let Coppola's vehicle pass. He was furious, and turned to his producer, Gray Frederickson, who had been with him since the first Godfather, and demanded, "Who was under the impression that we would be able to pass?" Frederickson just shrugged his shoulders, but Coppola fumed for hours. Several weeks later, when Coppola learned that his production was running over budget by considerably more than he had imagined, he again blamed Frederickson.

And then Winona Ryder arrived.

The young actress landed in Rome shortly after Christmas, accompanied by her boyfriend, TV heartthrob Johnny Depp. She had just finished work on Mermaids for Orion, and had only one day before she was scheduled for her first scene. She spent it at Cinecitta, the Italian film center where Godfather III was headquartered, being fitted and coiffed for the shoot. She appeared quite tired, and several production staffers noticed that something seemed to be wrong. But she had only a couple of lines to deliver the next day, and they let it pass.

(Continued on page 204)

(Continued from page 136)

She never answered her call. Later, Depp telephoned the studio and said that Winona wasn't well, that she couldn't get out of bed, and that she wouldn't be able to play her scene that day. Fred Roos, another longtime Coppola associate and a co-producer of the film, immediately dispatched the production's doctor to the young actress's bedside. After examining her, the doctor declared that Ryder was suffering from nervous collapse. She could not work, he said, and if she tried, she would suffer a complete breakdown.

The transatlantic telephone lines began to hum. In Los Angeles, Sid Ganis contacted Ryder's parents, and then Winona herself. "We tried to convince her that it would be O.K. to come back to work," Ganis says. "And we did everything from talking to the local doctors to trying ourselves to go over and reason with her: 'Winona, everything's going to be O.K.; these are friendly folks.' " It was to no avail. As soon as Ryder was able to steady herself, she and Depp got on a plane and flew back to California.

The production was thrown into a tailspin, and Coppola was beside himself. Again he blamed his producers. Why should he have to find out on the day that Ryder was supposed to shoot that she was too fragile to make it? Soon, Roos and Frederickson were dispatched back to the U.S., to work on the production from there.

Paramount denied that Roos and Frederickson had been fired from the set, but Coppola freely admits it. "I made a number of changes," he says. "I fired some people... . Simply speaking, my certain people, who are people that I like and that have a value, and are people that I brought back or had assembled here in the spirit of wanting to get all the original people back, basically were not living up to the standards of what it would take to pull this off."

Coppola, who'd spent ten years in directors' hell because of runaway productions, was now panicked that Godfather III was spinning out of control. He telephoned Fred Fuchs, his top Zoetrope executive in San Francisco, and instructed him to hire another producer, one who could help to keep a lid on the production. Fuchs found Chuck Mulvehill, a veteran independent line producer who'd worked for years with the late Hal Ashby.

"I think Francis felt that the picture was going to, or could, become one of these financial disasters," Mulvehill says. "And it felt to him that it was out of control."

By the time Mulvehill arrived in Rome, Godfather III was careening from a new controversy, what came to be known as "the Sofia revolution."

As soon as it had become apparent that Ryder was out of the picture, Fred Roos began to work the overseas phone lines, contacting talent agents for a replacement. He quickly found one—Laura San Giacomo. Coppola didn't want her. Roos presented some other names, which Coppola also rejected.

"High-anxiety time, that's what it was," says Sid Ganis. As the studio struggled to find a replacement for Ryder, Coppola came up with the idea of casting his eighteen-year-old daughter, Sofia, in the role of Mary Corleone.

It happened that Sofia Coppola was handy. She was a freshman studying art history at Mills College in Oakland, and had just come to Rome to spend Christmas with her parents. On the day that Ryder dropped out of the picture, Sofia was stepping into the shower at her parents' apartment when the phone rang. She answered it. It was one of the assistant directors, who asked to speak to Eleanor Coppola, Sofia's mother.

"I could hear it was something weird, just in their voices," Sofia says. ''And my mom hung up and said, 'O.K., Sofia, we've got to go to Cinecitta right away. You're going to be Mary.' I was like, 'Excuse me? Are you sure? I just want to take a shower.' "

Instead, she obeyed her father and reported to Cinecitta, where she read the part of Mary. Word of Coppola's decision to cast his daughter spread quickly, and by the time Sofia arrived, there were audible murmurs of discontent. She is a softspoken young woman, and although she has appeared in small roles in three of her father's films, she is not a trained actress. At best, she seemed miscast in the role of the frisky Mary Corleone, who carries out a dangerous flirtation with her murderous cousin, Vincent.

"The other actors were pissed," says one member of Coppola's team. "They felt that they had to act with her, and they hadn't been consulted."

"Obviously, part of the kind of daughter I wanted for Michael was my own daughter," Coppola says, "because I was thinking, Oh, if I were Michael, and I had this nice daughter, she'd be sort of like Sofia. She'd be cute, she'd be beautiful, but she wouldn't be like a movie-star beautiful. She'd be Italian, so in her face you could see Sicily. You know, directing is a very pragmatic business; you'll do anything to get the shot. And I looked around, and I saw where I was, and I saw that Winona was eighty-sixed, and I reached out for what I thought I could make it work with."

Sofia, meanwhile, had discerned that she was the source of this new tumult on the set, and it had a devastating effect on her. "Someone said to me, 'What are you doing? No matter how hard you try, no matter how great you are, people are going to slaughter you, because you're his daughter.' And part of me was saying, You know, it's just because I'm his kid." Sofia knew that Paramount wanted a star in the role, and that Sidney Ganis was en route to Rome. She also heard a rumor that Madonna was already packed and ready to come.

"I love Sofia very much," says one member of the production team who vigorously protested the casting, "but she has this teeny little voice like a little girl. He has fucked the love story."

One by one, members of Coppola's troupe went to the Silverfish, trying to talk the director out of casting Sofia. Coppola's sister, Talia Shire, who knew something about charges of nepotism from her own experience in the role of Connie, said, "Francis, don't do this to her—she's not ready."

A particularly poignant plea came from Richard Beggs, the sound designer, who'd recently lost his teenage daughter in an auto accident. "He came in here, right over there, and with tears in his eyes said, 'Francis, get her out of it—she doesn't want it. She's in tears over there,' " Coppola recalls. "So I go over to her and, sure enough, she's crying. Sidney Ganis and those guys are pacing out in the thing, the crew is waiting, and I said to Sofia, 'You know, this is going to be very hard, but if you really want to do it, you can do it. And what I suggest is, you just take ten minutes and you go in and you give it your best shot.'

"So she went down and she did it, and it was moving and everything. And that night she told me, 'Fuck 'em.' She said, 'I'll show them. I'll do it.' And when I saw that she had the strength to keep trying, I mean, what do I have to lose? If she kept trying and succeeded, fine. If she kept trying and didn't work out, I'd have to fire her and replace her anyway."

Coppola's mind was made up. "Basically, my decision was that I wanted to keep going. I didn't want to wait two weeks and hope that insurance would give us the money while we rewrote the part for Madonna—know what I'm saying?"

Sid Ganis couldn't believe it, and still seems a little rattled when discussing it. "Well, it was, uh, it was a crazy moment," Ganis says. "Francis came up with this idea that personally, to me, I mean, I know Sofia personally since she was an infant, so the concept of, in one twelve-hour period, of Winona withdrawing from our movie, leaving our movie, and Sofia being cast as the daughter was very strange."

The Paramount executive went to the actors and tried to talk Pacino into interceding with Coppola against Sofia. When Coppola found out, he exploded, and there was a new crisis on the set.

Coppola wrote a letter to his lawyer, Barry Hirsch, saying that Paramount was overstepping its bounds. "If they had any comment or disagreement, they had a procedure," Coppola says. "I didn't like it when they kind of went directly to my actors and said, What should we do?, and started to meddle. And I told them, pretty much, in so many words, 'Get out of the kitchen. Because that's not our deal.' . . .Bottom line: it wasn't up to them who I cast in the movie."

Nervous as the Sofia casting made the Paramount executives, Coppola was right. Frank Mancuso flew to Rome to try to calm the waters. He met with Coppola, first assuring him that he hadn't come to take over the production, or anything like it. Then he set up a dinner with the actors. "I told A1 and Diane and Andy [Garcia] that I absolutely believed that Francis was right and this was going to work," Mancuso says. "And basically what they said was 'Frank, if you believe in it, then we feel more assured.' They felt that if anybody had a lot at risk, it was certainly the studio."

Mancuso's assurances calmed Coppola too; within a few weeks, the director and Ganis were exchanging valentines. "Our film is looking rich, exciting, and full of the tension we've all been talking about," Ganis wrote Coppola in March, after seeing some of the edited footage. "The performances seem even beyond what we expected."

There was one more crisis in store for the Godfather III production before it left Rome, one that was potentially more awkward than the casting of the director's daughter. It was a lovers' quarrel between two of the film's leads, Pacino and Keaton.

The pair had been together, on and off, for years, living in Pacino's two houses in Sneden's Landing, New York, and in Keaton's home in Los Angeles. Pacino had preceded Keaton to Rome, where he took a villa, and when Keaton arrived a month later, she moved in with him. They had adjoining dressing rooms at Cinecitta.

But one morning Keaton arrived on the set with the puffy-faced look of someone who'd been on a crying jag, which, in fact, she had. Word quickly spread that Keaton and Pacino had broken up, apparently over his disinclination to commit. On-set romances always have a certain potential for bumpiness, but the PacinoKeaton bust-up created a real dilemma for the production: Keaton's character, Kay, and Pacino's character, Michael, were building toward their big scene together in the movie, a romantic reconciliation in the Sicilian countryside. "Most of us were concerned," says one member of the production team. "It was horrible to think that they wouldn't be speaking to each other. ' '

Then a personal sorrow intervened. Pacino's grandmother, a large figure in the actor's life, died in New York. Keaton accompanied Pacino to the funeral, and during the trip they reached an accommodation. A palpable strain remained, but the show went on.

By the time he reached Palermo, where he would shoot the movie's denouement, Coppola was almost jolly. He'd endured all the crises so far, disaster had been averted, Paramount had stood by him, and the studio bosses had loved the film he'd been showing them.

True, the production was over budget and behind schedule, but he was proud of his management performance. What was $5 million or $6 million in a $50 million film? Paramount's other big movies, Another 48 Hrs. and Days of Thunder, were also coming in in the $50 million range, "and they're not even trying to control costs," he says. Paramount really expected him to go over budget.

As for Sofia, she began a crash course with a voice coach, under the supervision of Fred Roos, and she will loop over her lines later in the production. "She will be a different actress," Roos says.

It is dark inside the Silverfish, except for the light from one of the monitors, on which Coppola is showing a scene from Godfather III. On the screen, A1 Pacino as Michael Corleone is in a room full of important guests, watching his daughter, Mary, as she presents a fat check to the Corleone-family charity foundation. Michael is old and sick, white-haired and sallow, yet he is clearly happy. Watching Michael gazing at Mary, Coppola says, "He is proud."

The director seems astonishingly impervious to the criticism that his decision to cast Sofia as Mary caused. And it is quite clear, watching Coppola watching his daughter, that in some way the bizarre Winona Ryder episode and her replacement by Sofia was inevitable, that Sofia had to be Michael's daughter, because she is Coppola's daughter.

Coppola's films are intensely personal—not just his arty experimental movies, but even his big-budget studio films like the Godfather trio. Especially the Godfather movies. When Coppola made Godfather II, in which Michael Corleone, at the height of his power, was building, strengthening, and consolidating his Mafia empire, the director was in the midst of his own empire-building phase. He was creating his studio, buying a building in San Francisco, acquiring a magazine (the now defunct City). "To some extent I have become Michael," he said at the time. It seemed an egotistical director's glib conceit, but he was right.

It is also clear, watching Coppola look at his film, why this third Godfather couldn't be any of those things that the other writers (including Mario Puzo) wanted it to be. It had to be a tragedy inspired by King Lear, with its old man lost on the heath, his kingdom slipping from his grasp, because Coppola now sees himself as Lear, his life in the tragic phase. "It's no surprise to me that, whatever movie we're making, our personal lives seem to go [parallel] in an uncanny way," he says. "Wherever I've been at, in the different movies I've made, my life was sort of at that point, too."

Quite aside from the professional jolts he's endured, or even the threatened loss of his personal property, Coppola suffered the ultimate tragedy four years ago, the death of his twenty-three-year-old son, Gian-Carlo. "Gio," as he was called, had been to Coppola what Pinocchio was to Geppetto: an idolizing son who wanted nothing more than to become a man like his father. He persuaded Coppola to let him quit school at age sixteen to work as his apprentice, and he grew to be a respected member of Coppola's filmmaking team. He was serving as the electroniccinema supervisor of Coppola's Gardens of Stone and had the promise of his first independent movie work when he and Griffin O'Neal, who had a small part in the movie, had a motorboat accident near the film location in Maryland. Gio was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. Four years later, Fred Roos says, "Francis is irrevocably different because he lost his son; it's like a chip in his whole psyche."

Now, sitting in his Silverfish, Coppola talks passionately and at length about Gio and the tragedy of unrealized promise. "You know what my greatest sadness is, beyond the obvious one? It is that he was a talented kid, and he showed a lot in those few years.... Everyone lives a certain length. I just feel sad that he didn't get a chance to show a little more—he was going to do something beautiful.

"Steven Spielberg had called me himself, and he said, 'You know, I was looking at Gio's stuff, and we feel that he can direct an "Amazing Story." And I just want to ask you frankly, do you think he could do it?' And I said, 'I'm sure he could do it. And I'll tell you what, if he wants to do one'—I know he had an idea about a magic carpet—and I said, 'I'll write it for him.' And it always made me sad that he could have done that. I would have had one film, and people would have thought of him as what he was, which was a very serious kid." He chokes for a moment. "I mean, a serious kid of the cinema.

"But that is the human fate. You're going to have a tragedy. We're all going to have two more, three more tragedies, because you cannot get through life without ever having tragedy. Would you want to?.. .The point is, tragedy is one of the elements of human life, and therefore is also beautiful. And there, that's where you get into the emotion and the space when they write great plays and stuff. And that's what we would like to do even with this tawdry story of a bunch of Mafia guys. We want it to stand for us, you know?"

It is a revealing stream of consciousness, a word journey from Gio to tragedy to Michael Corleone. This Godfather had to be a tragedy, and Michael Corleone had to suffer it, because Coppola did.

At the end of the day's shoot, little Gia Coppola, the child that Gio's girlfriend was carrying when he died, runs into her grandfather's arms. The threeyear-old has been working, in a manner of speaking, playing one of the Corleone bambini in the film—another Coppola put to work on Godfather III. As usual, Coppolas are all over the place: Coppola's mother, Italia, is lounging inside the villa, waiting for her husband, Carmine, who is scoring the film. Coppola's daughter, Sofia, and his sister, Talia, are playing major roles. Carmine's brother helped create a musical segment.

Family is Coppola's context, the environment he feels comfortable in, and therefore the environment he creates, even in his work. He finds magic in the idea of family, and comfort in its noisy reality, in the women, the children. "That part of life is very attractive to me," he has said. It is also, in a practical sense, a useful tool for his craft. "A lot of the reason I use my family is because traditionally they always came through for me. The reason I like to use my father—if I were to call my father right now and say, 'Dad, I want a young girls' choir doing a Bachian arrangement of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star," ' tomorrow the little girls would be there and they would be doing it. So it's a little bit of the circus-family mentality; we do have a tradition in our family of just pulling the kids in. And the kids have been around it all their life, and you say, Sink or swim. And if they sink, they were supposed to sink. And if they swim, then you gotta know they're a talented person in the family, or a person who's gonna now be part of a wonderful tradition of show business."

It works for Coppola, but it's not always easy to be part of his family. Talia Shire has a theory that she thinks explains Coppola's casting of Sofia. "He's now focused on Sofia and protecting her, which gives him a solid base. He's not thinking of all the other insanities. It's like a diversionary thing. Therefore, it's a very fine thing for him. It's rough on her. Rough on her. She doesn't deserve this. Doesn't deserve it. Because she is basically structuring her father in this act, and she's doing a damned good job."

That's a pretty cold-blooded purpose, if Shire is right, but it is one that the lovely woman with the sad eyes quietly lingering in the background of the production wholly understands. Eleanor Coppola, Francis's wife, has spent twenty-seven years in his background. She married Coppola, three years her junior, in 1963, when she was, as she puts it, at the "old-maidish" age of twenty-six. She is a bright, cheerful person, but she also carries the aspect of a wounded soul. Like Michael Corleone's wife, Kay, she is a non-Italian, a modem American woman who has been forced to come to terms with her husband's very Old World view of family and her place in it, or get out—a circumstance she wrote eloquently about in a diary she published as Notes, based on her tortured relationship with Coppola during the making of Apocalypse Now.

"All the time we have been married I have wanted to do some kind of work," she said. "It always took a back seat to whatever Francis was doing."

During a fight in the Philippines, where he was shooting Apocalypse (and where he began an affair with a young protegee), Coppola told Ellie that "all he ever really wanted from me was to make him a home. ... He would spend a million dollars, if necessary, to find a woman who wanted to make a home, cook and have lots of babies. I could never tell the truth, even to myself, because I thought it would be the end of my marriage. I am not a homemaker. I have always wanted to be a working person. But the kind of work I have done over the years hasn't earned any money, so it looks like I am playing and lazy."

At one point, thinking of similar feelings that Jackie Kennedy must have experienced as First Lady, Ellie wrote, "There is part of me that has been waiting for Francis to leave me, or die, so that I can get my life the way I want it. I wonder if I have the guts to get it the way I want it with him in it."

/^oppola is having dinner at the RistoV_>« rante Chamade in the seaside resort town of Mondello, a few miles out of Palermo. He is with a party of ten, including Sofia and Eleanor and two French film distributors, old friends and supporters of Coppola's, who have brought their families. Although they are sitting at a round table, it is clear that Coppola is at its head, which always seems to be his natural place.

One of his European friends has just recounted a rumor he's heard that Godfather III is wildly out of control, prompting an animated refutation from Coppola. "How can you make a movie and pay A1 Pacino $5 million and Diane Keaton $2 million and try to make it for under $50 million?" Coppola asks. "And the fact is, we're not even 10 percent over budget."

He takes a bite of fried calamari and adds, with a chuckle, "We will be tomorrow, though.

"But enough of this," he says to his friend. "You've just come from Paris. Tell me about food, and wine, and life." To which his friend replies, "Francis, what can I tell you about life? You are life!"

Coppola is pleased, and clearly in his element, holding forth with a group of admirers and family, eating fine food at the end of a long week's shoot. He is a devout hedonist, as his expanding girth attests, and maturity has done nothing to temper his lifelong taste for fine living. (During the filming of Apocalypse, Ellie warned him that "he was setting up his own Vietnam with his supply lines of wine and steaks and air conditioners.")

He had come to Italy not knowing for sure how the film would conclude, a circumstance that had been problematic in the past. At Cinecitta, over the slight objections of Paramount, he had produced a twenty-minute opera sequence: a section of the Sicilian opera Cavalleria Rusticana, which concerns itself with the same themes as Coppola's movie, and, indeed, the overriding theme of all the Godfather films—La Vendetta. Coppola had tentatively planned to end the movie with the assassination of a corrupt archbishop. But what he really wanted to end with was a bloody montage, cutting from the opera (where Michael's son, Tony, was singing the lead) to scenes of mayhem outside the opera house, in the manner of the baptism scene in the first Godfather movie. But to do that, his opera scenes would have to be just right—' 'They would have to be beautiful."

They were beautiful. And the ending he finally came up with surpassed his own best expectations.

"It's going to be very, very spectacular," he says, his voice dropping in a kind of reverence for this scene that has come to him. "It's going to be heartbreaking. And it's going to be, hopefully, what you want for a piece like this, a tragic piece, where you really, somehow, even though you don't understand it, you come to be that much more familiar with the fate of man, all of us, all human beings, who, in their small ways, act out that story. Those kind of characters, tragic characters, are always so appealing to us because we see our own fate somehow, what it is to be a human being and to have your heart broken, or to consider your own death, or to wish to atone for your sins. All of those themes, I think all people, when they think about themselves and their life, and not just the bullshit of how they fit into their society, that's what tragedy's supposed to do. To move you on that level. And that's what I wish to be able to do."

On the set or in his Silverfish or at a meal, Coppola manifests an odd and compelling charm. In his rumpled cotton suits and wild ties, he conveys a disarming openness with a body language that is utterly unself-conscious (vigorously scratching any itch as soon as it occurs) and an abiding willingness to expound about his wide-eyed visions.

"He has charisma beyond logic," George Lucas once explained to his own biographer, Dale Pollock. "I can see now what kind of men the great Caesars of history were, their magnetism. That's one reason I tolerate as much as I do from Francis. I'm fascinated by how he works and why people follow him so blindly."

Standing in the large, open-air temporary commissary set up at the edge of the villa's side arbor, Coppola laughs heartily at a joke he has just made. Talking about the opera scene and how beautiful it is, he says that maybe he should send Paramount executives a telegram telling them, "The bad news is we don't have a movie, but the good news is we have a twenty-minute opera cassette that you can syndicate." He notices that his laughter has attracted the attention of the lunching production troupe, and speaking of his mirth, he says to them, "It's been like this the whole time, right?"

Everyone gets the joke, of course, because it hasn't been like this throughout the production, nor will it remain this way for long. Every day, Coppola arrives at the set wearing a cotton suit, a different color for each day—black, olive, sepia, and so on—and he changes moods the way he changes suits, only more often. The next morning, he is on the set early, screaming his displeasure over a setup that wasn't working out to his satisfaction.

"Time to get the lithiiiiiiuuuuummm," an assistant whispers to a colleague, just beyond the reach of Coppola's ear.

"What's the matter?"

"He's yelling."

"Who?"

"Francis. Fifty days he doesn't come near the set, and now he won't leave."

There are those moments when Coppola is a tyrant, and yet there are just as many moments when he is almost childlike in his sweetness, stopping suddenly when he sees a child near the set, and pulling a windup toy ducky from his pocket and enjoying its antic movement at least as much as the kid.

The opposing sides of his character, and for that matter of his work, seem so pronounced. He loves to surround himself with family and friends, and yet he retreats to the stark solitude of the Silverfish. He is compelled to experiment with cinema and strive for art, and yet his masterwork is a phenomenally commercial gangster saga. His language is the visual narrative, and yet he is at least as interested in the technology of his craft as he is in the art of it. He can seem so wired to the longings of popular culture—The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, American Graffiti, which he championed for Lucas and also produced—and completely disconnected from them, as demonstrated in One from the Heart.

And though he was driven to succeed in the movie business, and was, arguably, crushed by his ambition, he is forever vowing to leave commercial filmmaking. After shooting Tucker, he said, "I just don't want to be doing this anymore," and once again swore that he'd quit to make experimental little "amateur" films. He would even take up sculpting, he said.

"That's my hurt feelings," he says now. "That's me saying, Why, basically, is it so hard to get people to want to accept what you want to contribute? Why is everything so slow and sticky like molasses? And then you say, Well, the hell with it, I just won't try to do it anymore. If it can't be easier, and more with the focus on the work and the learning and the experimentation, if it's just going to be all this other—how do I stand, and do they like me, or do they think I'm cool or not—then I'd rather get in another place."

Although Peggy Sue was the only money-making movie Coppola worked on during his decade-long tenure as a director for hire, the period strongly bolstered his financial circumstances. While he was never able to consolidate his movie earnings into an assets empire like that of his friend George Lucas (whose vast holdings in Marin County's Lucas Valley served as a reminder to Coppola of the advantages of catering to popular taste), he owns homes in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Belize, and the Napa Valley, where he has his jewel, a 1,500-acre estate in the heart of what was the old Inglenook estate. Coppola and his family live in a gracious Victorian mansion on the estate, and a nearby carriage house, three stories tall, serves as his library, sound and editing room, and winery. Coppola has become quite serious about his sideline as a winemaker, and his prized vintage, the Niebaum-Coppola Rubicon, was honored two years ago as the first California wine selected for the exclusive wine list of the Taillevent restaurant in Paris.

After making Tucker for Lucas, Coppola estimated his worth at $50 million, and although he complains that his current difficulties over that long-ago One from the Heart debt not only cost him his studio but are "about to take everything else," he allows in more moderate moments that "we're very secure and we have the resources to move ahead."

And now Coppola is allowing himself to think about the possibilities that the success of Godfather III might bring, and about what he might do next. Maybe Sony would ask him to move into its newly acquired MGM lot in Culver City, where he could put his years of technological expertise to use for sympathetic patrons and build a cinematic city of the future.

Or maybe he would go back to Napa and make a little film in his backyard, to recover from the insanity of making an epic-size movie.

Or maybe he would return to the project he'd been working on before Mancuso gave him the Godfather III job. It's a movie called Megalopolis, a sort of reworking of the story of Catiline's conspiracy against Cicero and other consuls of the Roman republic, applied to modem New York City, with an Ed Koch type as Cicero and a Claus von Biilow type as Catiline.

"That is a movie on a bigger scale than this movie," Coppola says with the old enthusiasm. "It will probably cost more, and it's really experimental. So it's always fun when you do little experimental films, but it's even more fun to do a big experimental film."

Coming back to The Godfather seems in some way to have evened out Coppola's wrinkles. He is increasingly convinced that he is making a very good movie, possibly even a great movie. "I've felt the consistency of this movie is more mature and more beautiful and more thought out and more together. And it's just sort of more cathedral-like than the other movies. And it takes on more and it delivers on it, hopefully."

It is a justified optimism. Judging from pieces of the movie already edited on videotape, Coppola's choices seem absolutely correct, his instinct rediscovered. Sofia wouldn't have worked in the role of Mary as the character was conceived, but she fits nicely in the new concept, and is almost necessary to the force of the ending Coppola plans for the film. Her understated presence—the fact that she's an amateur, if you will—adds to the homespun look that Coppola and cinematographer Gordon Willis achieved in the first two Corleone movies. Willis's meticulous photography proved a source of maddening frustration to Coppola during shooting, but his pictures are again exquisite, and Pacino has absolutely transformed Michael Corleone from the elegant young don at the top of his strength into a slumped Lear on the heath.

After his long and fevered quest for artistic greatness, Coppola seems fittingly at ease with his "tawdry" gangster movie, and almost at ease with the world.

"The hardest thing about writing, or being an artist, is that 'Have you gotten enough validation?' I really think that until a person can get it out of his system, especially in the arts, 'Oh, yes, I have some value; yes, I have gotten that validation,' only then can you go on to just be a normal person. It doesn't take a genius to know that even if you are a terrific filmmaker, you are not the best who ever lived. Even if you are a terrific painter, there are 50,000 other guys who make you a dwarf. ' '

He has, he says, begun to come to terms with the criticism he has generated, both from the press and in Hollywood, which in the past he has lambasted as obtuse attempts to thwart his genius.

"You know, I once saw a bullfight for the first time, and it was a very famous bullfighter, and he was in there and I thought he was doing pretty good. And the crowd was booing, and I said, 'Jeez, they're so rude!' Until a guy said, 'Listen, they're in the sun, paying $4.30, for which they had to work all week, to sit in the sweating sun, and he's getting $50,000 for this hour—he's gotta be great!'

"And that's the way I see it in terms of the world fame. It's not that the press or individual writers are saying, 'Oh, he's not a nice guy.' They're saying, 'Look, if you're standing where he is and you're commanding the attention of the world, you've got to do something. You have to live up to it each time you make a film.' I'll do my best. I don't know if I'll live up to it. I hope I'll live up to it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now