Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMITCH SNYDER The Darkness Within

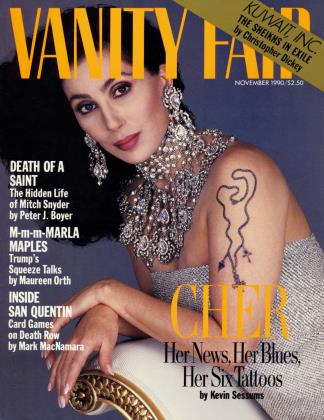

Did Mitch Snyder, the passionately committed activist whose hunger strikes made America's homeless into a cause célèbre, really kill himself over a failed romance? It seemed an unlikely and incongruous end, but, in interviews with Snyder's family, his friends, and his lover of thirteen years, Carol Fennelly, PETER J. BOYER unravels a torment of passion

No, he's not here," the young woman told the reporter on the telephone, adding that she had no idea where Mitch Snyder was or when he was coming back.

Overhearing this exchange in the third-floor office of the Community for Creative Non-Violence shelter, Marsh Ward felt his heart start to race. Ward, a psychiatric social worker, had been with the CCNV homeless shelter nearly three years, long enough to know that when Mitch Snyder wasn't available to the press something was badly amiss.

Snyder's special touch with the news media was central to his magic: it was how he'd found an audience for his brand of political theater, a seventeenyear run of "radical Christian'' agitation and life-threatening fasts that made homelessness the unlikely pet social cause of the 1980s; it was how he'd forced Ronald Reagan to give him the huge CCNV shelter (the world's largest); it was how he'd brought an enraptured Hollywood to his aid—marching by his side, funding his crusades, and making the ultimate gesture, a TV movie about his life. The shelter staff knew that media calls always required priority handling, whether Snyder was out of town or just in his room taking a nap. And it was especially so on that sultry afternoon of July 5, with a major funding battle with the D.C. government brewing.

So when the young volunteer told Ward that she didn't know where Snyder was, that nobody had seen him for a couple of days, and that Snyder's door was locked and staffers hadn't even been able to feed his cat, Ward felt a black intuition wash over him. He summoned the floor manager, and together they made their way down the dormitory hall to Snyder's suite of rooms. The doors were locked, and the keys didn't work. Had Snyder changed the locks? Finally, a key to one of the rooms was located, and Ward entered. Nothing. He tried the handle of the door to the second room, and it turned. He opened it and saw Mitch Snyder, his back to the door, hanging at the end of a heavyduty electrical cord.

"Carol and Mitch were fascinated with each other's potential violence."

It was obvious that Snyder had been dead for some time, a day, possibly two. The cord had been stretched by his weight, and his feet (in his familiar boots) were sprawled on the floor. Ward stepped into the room and cut through the thick yellow cord with a butcher knife fetched from the kitchen, then laid Snyder down on the floor. He knew Snyder was dead, but he was struck by the awful thought of people later asking, "Did you give him mouthto-mouth? Did you take the cord off?'' So he knelt down and removed the cord, which had been wrapped twice around Snyder's neck. He didn't try to resuscitate him; Snyder's left eye was partly open, and his skin as cold as stone. "I could just see that he was gone,'' Ward recalls.

Soon enough, there were cops all over the place (the police chief himself showed up), and politicians (Jesse Jackson, Mayor Marion Barry), and, of course, reporters. And when the moment came for something official to be said, as so often before it was Carol Fennelly who said it. Fennelly had been spokeswoman for the Community for Creative Non-Violence all through the decade of high drama when Snyder's fight for the homeless made national news; she was a dedicated activist with the instincts of the most practiced P.R. operative, a radical with a Rolodex who made sure that Snyder's denouements were attended by the validating whir of news cameras. But Fennelly and Snyder had shared more than a mission; she had been his girlfriend for thirteen years.

Now she stood in the rain before the cameras, obliged to announce the end of the story of Mitch Snyder. It was an extraordinarily poignant moment, made more difficult by the fact that police had leaked the information that Snyder had killed himself over a failed romance— and everyone knew that meant Fennelly. She vowed that the struggle would continue, and, through tears, added, "Mitch always said good things happen with rain; he was wrong today." But even as she spoke, she was aware of the sense that somehow Snyder's death (and her role in it) was inadequate to his life, that suicide seemed a low mockery of all the near-death fasts. His life had been his capital, and his willingness to spend it for his cause had been a righteous sword to the throats of the enemy; it gave him a moral power that so many found irresistible. To spend it (wasn't it wasting it, really?) on a disappointment of the heart, like a lovesick swain, was an ending that didn't fit.

Three months before his death, Mitch told Berrigan,"They're all turning against me."

Perhaps that is why so many who believed in Snyder would arrange their own endings, would have it that Snyder really died for his cause. Snyder's mentor and friend Phil Berrigan, for one, would equate Snyder's suicide with that of Roger LaPorte, the twenty-one-year-old seminarian who in 1965 immolated himself on the steps of the U.N. building to protest the Vietnam War.

But the full story of Snyder's death, which Fennelly couldn't tell, would have made all the pieces fit. It is the story of a passion poisoned by abuse and betrayal, of a private, violent rage, of tragic miscommunication and an obsession that slipped to the edge of madness, ending in a final gesture of cruel and lasting revenge.

It is a love story.

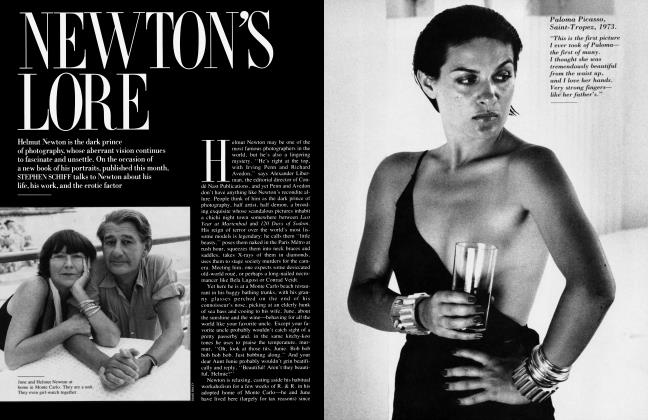

In her room on the third floor of the CCNV shelter (the abandoned college building that Snyder wrested from the federal govern ment), Carol Fennelly seems the very incarnation of the nesting instinct. The room's institutional chill is warmed by plants and pictures, and on the VCR at the foot of her bed sits a Jane Fonda workout tape, testament to a ceaseless weight alert. At forty-one, she is an at tractive woman, with deep-blue eyes, tight wavy hair, and features that resem ble the Kennedys', Fitzgerald strain. She has an easy laugh and a ready smile that produces twin dimples on either side of slightly bucked teeth, and in this room, with its stuffed animals bunched neatly on the pillow and the nightgowns hanging on the door, Fennelly takes on a sweetly girlish aspect—somebody's divorced mom, going back to school.

But there are hints of the darker side of her life, a slightly spooky side that is always very close. You see it when she offhandedly says that this is the suite of rooms she shared with Mitch, that through the open door, just three feet away, is the spot where he hung himself. You see it in the suddenness with which the bright smile becomes a teary pause, and you see it on the nightstand next to her pillow, which holds a wooden urn containing the ashes of Mitch Snyder.

It is in this context that she says of her life with Mitch, "Changing the world is addictive, and we became addicted to it. I became addicted to Mitch, and Mitch became addicted to me.'' And you believe her.

For Fennelly, at least, it was addiction at first sight, which happened on a rainy winter day thirteen years ago. "I met Mitch Snyder on January 7, 1977, on a picket line in front of the District building,'' she says, as if sounding a liturgy. "It was cold and raining, and he was wearing Levi's, a black turtleneck, and a burgundy jacket." Fennelly was twenty-seven, a decade away from her Southern California girlhood in a working-class Mormon home. After high school, she had yielded completely to the rebellious urges of the sixties, joining a commune in Pismo Beach, working in a head shop, and having two babies. She and her "old man" briefly tried marriage, and moved to an Oakland suburb, where, in 1975, in fairly quick order, she lost the husband and found God. A voice came to her while she was folding clothes, telling her that "special work" awaited her and her children, and when a new romance led her to Washington, D.C., she started a day-care center and associated herself with the left-wing evangelical Christian group Sojourners.

It happened that the Sojourners were working together with a local radical Christian group, the Community for Creative Non-Violence, on a project to pressure the federal government to turn over an abandoned house it owned on Fairmont Street for use as a shelter for the poor. And after a day of picketing, Carol caught a ride to a house where Snyder was handing out leaflets, and he came up to the car, peered into the window, "and that was it," she says.

"I was so.. .what was the word they used in The Godfather? Thunderstruck? I was speechless. I couldn't talk. It was one of the few points of my life when I was ever speechless." Then, a couple of days later, she attended a community party, where she saw him again. ''I just couldn't stop staring at him all night. And at one point—he used to smoke in those days—he went out to the front steps. He was wearing a yellow turtleneck—I still have that sweater someplace—and Levi's.

Tight Levi's. And so I walked outside, just sort of accidentally, not meaning to find him there, and it was just really coincidence. And I thought, Oh, God, here's my chance! I can talk to him. And I stood there, and I couldn't say anything. So I asked him for a cigarette, and I didn't even smoke. It was terrible."

By that time, the man in the tight jeans was a legend just bursting to unfold.

Snyder was six years older than Carol, but in those short years he'd lived a whole separate life, one that would haunt him forever and compel him to his mission to change the world.

Mitchell D. Snyder was bom in Brooklyn on August 14, 1943, into a family that might be characterized by a modem sociologist as dysfunctional. His parents were Jews, but fervently atheistic; his mother, Beatrice, was a warm and gentle woman, perhaps even a bit smothering, but his father, an executive in an electrical-manufacturing firm, was aloof and cold—perhaps because his own parents, though married, had sent him to an orphanage as a child.

When Mitch was nine, his father left home for another woman, and died a few years later. Suddenly, Beatrice Snyder was raising two children on her own; her daughter would soon marry and move out, but young Mitch was devastated by his father's abandonment. ''He never had the father that he needed, you understand?" Beatrice Snyder remembers. ''Up to a point, a boy needs his mother. And just when he needs his father most, at nine, that's when he had no father." Beatrice went to work as a private nurse, rising at four each morning to prepare meals for Mitch, getting by on soup and sandwiches herself when money was tight. ''This was my baby," she says. ''I adored that boy—I adored him, he adored me. [But] my husband was the strong one. See, I was like putty in Mitch's hands. I spoiled him. I have to tell the truth, I did."

While Beatrice worked, Mitchell pursued the dubious life of a Brooklyn greaser, joining a street gang called the Flatbush Tigers, hanging out, busting into parking meters just to hear the jingle of the coins. He dropped out of Erasmus High School when he was fifteen, and by the time he was sixteen he'd been arrested more than a dozen times. Thinking that a boy with Mitch's intellect might be turned around, the authorities sent him to the Hawthorne School, a kind of reformatory for rich kids, but he was booted out after a year.

Back in Brooklyn, he went to work at odd jobs, and even took some classes at night school, where he met a young nursing student who would become his first serious romance. Ellen Kleiman was a shy, quiet girl, the daughter of hardworking Jewish immigrants who'd made a success of their lives in New York. Hers was a cloistered and simple family life, very oldworld, a universe apart from the roiling conflicts that clogged the air of the Snyder household. In that time of the Angry Young Man and the Rebel Without a Cause, Ellen Kleinian saw something in the brooding Mitchell Snyder, a wounded-animal allure, that she couldn't resist. ''There was an aura of sadness around him," she recalls, ''and I think that's what drew me to him." And could he talk! When he wasn't brooding, Mitch could make rhapsodies out of words, sometimes speechifying to an audience of Union Square derelicts just for the joy of it. To the everlasting disappointment of her parents, Ellen married him.

He worked as a vacuum-cleaner salesman and at a number of other jobs (' ' God, there were so many," Ellen recalls), and came near hitting bottom a few times, but by the time Mitch was twenty-six he had a well-paying job on Madison Avenue as a headhunter for Management Consultants Inc. Soon he and Ellen had two boys, Ricky and Dean, and seemed to be on their way to the domestic reward Ellen had hoped for. "He was very good at that job because of the way he speaks," Ellen says, "and he really enjoyed it. . . . But it wasn't what he wanted to do for the rest of his life."

(Continued on page 239)

(Continued from page 175)

It turned out that it wasn't what he wanted to do for the rest of the week. It was 1969, when the very times beckoned to the anarchic in every young American soul, and Mitch Snyder wanted out. He saw himself turning inward, evolving into his father; sometimes in the middle of the night, Ellen would be awakened by anguished cries from her sleeping husband. "I'd hear a moan, and the pillow would be wet with sweat," she says. "I used to wake him up, because he would frighten me and I didn't know what was bothering him. And he'd say, 'Nothing, nothing, go back to bed. A bad dream, bad dream.' And he'd never confide in me what the bad dreams were. I think it was just basically all his fears that would come out—he was always on guard during the day with his feelings. And during the night, of course, that's when our demons come out."

And one day he left. Just hit the road and vanished, leaving Ellen and his two boys to make do on assistance from her folks, and welfare and food stamps. In 1970 he was arrested in Las Vegas for driving a vehicle that had been rented with a stolen credit card. He swore he'd been set up, but he was convicted, and served time in California before being transferred to the federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut.

On the day Snyder entered Danbury Prison, lightning struck. Someone pointed out a tall, dignified, gray-haired man strolling the prison yard, followed by a group of inmates. "That's Phil Berrigan," Snyder was told, and the name meant something even to the brooding young man from Brooklyn. Berrigan and his brother Daniel were superstars of the cultural revolution that swept through the 1960s, radical Catholic priests whose theology basically held that Jesus was a radical and that's why He was killed. They'd rebelled against their church and their government, which insisted upon jailing them for such acts of conscience as pouring homemade napalm over draft records. They were, in short, the answer to Mitch Snyder's night dreams.

Snyder walked right up to Phil Berrigan and said, "I have a feeling that you know something that would be helpful to me. I want to spend some time talking with you and getting to know you. Is that O.K. with you?"

Of course, Berrigan said, and the brothers started right in on the matter of converting Snyder to their cause. They'd meet in the prison library or in the bleachers by the prison softball field, under the guise of a Great Books club, and they began with the Gospel of Matthew, which was highly apposite: Matthew was a Jew, a rich man, a tax collector who was hated until he renounced his wealth and followed Jesus. Phil Berrigan, like Ellen Kleiman, was struck by Snyder's way with words. "He was extremely verbal, and sharp," he recalls of his young prison neophyte. "Good mind. He more than said his piece at gatherings."

Snyder eagerly converted to Catholicism, with Dan Berrigan baptizing and confirming him right there in jail. He now believed himself to be called by God to agitate, which made him a prophet, instead of the mere sociopath he'd been well on the road to becoming.

The new convert impressed his mentors with his organizational skills and with his nerve. At the cost of a stint in solitary, he led a work stoppage that shut down the prison for eight days. "It was an incredible piece of work," Phil Berrigan recalls. Snyder's prison protests also ruined his chance for parole, and he served his full term. When he got out in the summer of '72, the anti-war movement was beginning to peak. As many radicals began to be absorbed by Watergate, disco, and the national malaise, Mitch Snyder went looking for his cause. That's when Tom Ireland, an ex-con pal from Danbury, called and invited Mitch down to visit something called the Community for Creative Non-Violence.

The community had been created in 1970 by a Paulist priest named Ed Guinan. He, too, was a runaway from the mainstream, a San Francisco financialmarketing executive who was inspired to join the priesthood by the teachings of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, 1930s-era Catholic radicals who espoused "a complete rejection of the present social order and a nonviolent revolution to establish an order more in accord with Christian values." The Dorothy Day creed also called for the establishment of "houses of hospitality"—communities, or communes— to care for the "wrecks of the capitalist system."

Guinan realized that the war wasn't America's only national sin; there was also the plight of the poor, the underclass. In the fall of 1972, just weeks before Richard Nixon's re-election, the CCNV opened its first soup kitchen, with Mother Teresa of Calcutta on hand to help serve.

As the community grew, it evolved in two directions, an activist wing that focused on anti-war protest and a serviceoriented faction that tended to the needy, providing shelter and a medical clinic. When Mitch arrived, he was naturally drawn to the activist side, and soon emerged as a leader of the radical resistance to the war. But when the war ended, there was only so much to radically resist in the tenure of Gerald Ford. For a time, Snyder's focus drifted. Then, one morning in 1975, the community members heard a noise outside, the unhappy sound of a neighbor being evicted into the street. Snyder had an issue.

Discovering that the city owned huge chunks of abandoned property, the community developed a plan: they'd go to the government and ask for an abandoned building to use for emergency shelter. When the city refused, Snyder led a band of community members to their target building, ripped down the front door, and occupied it until police removed them and put the house under twenty-four-hour guard. The community responded with a campaign of pickets and protest leaflets.

And that is what Mitch Snyder was doing on that January afternoon when he approached the car from Sojourners and started a conversation with the pretty California girl riding shotgun.

"My relationship with Mitch was always very difficult and very painful," Carol Fennelly says. "There wasn't a time from the day that I met him that that wasn't true."

When Mitch Snyder became a Christian zealot with a mission to change the world, he didn't also become a nice guy. A prophet, perhaps, an uncommonly effective activist with an unswerving devotion and drive, certainly, but on a personal level he could be selfish, aloof, bullying, and sometimes downright mean. It was a side of Snyder that would eventually bring him into conflict with the movement and with his own community, a side that Carol Fennelly, who played right into it, knew most intimately for thirteen years.

There was heat from the moment they met outside that picket line, but Mitch wasn't exactly available at the time. He'd been living with a CCNV member named Mary Ellen Hombs, a tall, slender, deeply intelligent and devoted activist. Carol and Mitch began seeing each other while Mitch was still living with Hombs. Even in the sharing atmosphere of the community, this was not a fertile circumstance for new romance, so Fennelly went off to work with the poor in Los Angeles, leaving Snyder and Hombs to work things out.

After less than a year, Snyder asked Carol to come back, and she did, with her two kids in tow. Snyder neglected to mention her return to Mary Ellen, and even after he moved in with Carol, Mary Ellen remained a forceful member of the community, and a continuing source of insecurity for Fennelly. The two women went without speaking for ten years, four of which they spent under the same roof.

But in the early flush of her new life with Mitch, it was possible for Carol to push all of that aside. Their radical romance bloomed in a tiny "drop-in center" on Twelfth Street, where they'd provide coffee and showers for the homeless during the day, and serve a meal in the alleyway at night. "All we had was this alley," Fennelly remembers. "And Mitch and I used to go out back at night, and there'd always be a bottle of Wild Irish Rose passing around, and we'd always have plenty of bread—never a shortage of bread—and so we would sit out in the alley with the folks, you know, and eat dinner and pass around a bottle of Wild Irish Rose and eat bread. And it felt like it was the absolute liturgy. And it really was."

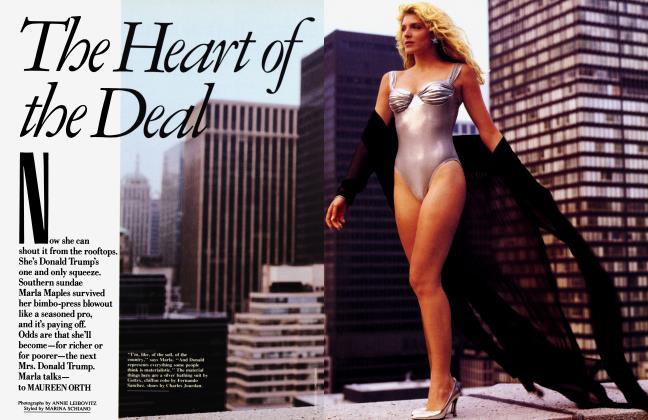

In his particular way, Snyder cut a compellingly romantic figure. With the arrival of the eighties and the age of Ronald Reagan, Snyder was a man finding his moment every bit as much as the Donald Trumps and Ivan Boeskys were finding theirs. The combination of Reaganomics and the administration's policy of deinstitutionalizing large numbers of the nation's mentally ill populated America's streets with lost and wandering souls almost overnight. And Snyder was a man who recognized opportunity when he saw it.

Wearing his radical uniform—jeans, army fatigue jacket, and boots—Snyder became a kind of droopy-eyed, mustachioed reverse image of those Vietnamgeneration strivers who hit the eighties running, bent on answering the hormonal call for achievement. In his context, he was as ambitious as any of the young investment bankers clogging Wall Street. He didn't just become a quiet advocate for a cause he believed in, he became a superstar. "This is not a Don Quixote (for whom practical minded Americans have little use), or a suffering saint," wrote sociologist Victoria Rader, who conducted a three-year study of the CCNV. "Snyder is an American entrepreneur, and the public is impressed." It was a measure of his charisma and drive that in an era that prized individual achievement and success above all, Snyder made a national cause of people who embodied the antithesis of those values.

He succeeded because he was intractable and imaginative in equal measure, and because he was naturally inclined to the preposterous gesture, such as the infamous "piece of the pie" incident in the early days of the Reagan administration. Congress had just passed the Kemp-Roth tax cuts, a key element of the famous "trickle-down" theory, which held that all segments of society would eventually benefit from increased wealth at the top. To help peddle the idea to the public, the American Conservative Union dreamed up a publicity stunt featuring the world's largest pie, a seventeen-foot creation that would be sliced and distributed to all in attendance as a way of demonstrating that "everyone will get a piece of the pie."

Snyder and the CCNV saw a perfect chance to assert a countermessage. Five members of the community dressed up in oversize business suits, each wearing a tag that bore the name of one of Reagan's conservative friends—Joseph Coors, Alfred Bloomingdale, et al. Snyder drove them to the event, where, to the astonishment of all, they stomped into the middle of the huge pie, sloshing around and shouting, "It's all for me! It's all for me!" To get them out, security guards had to wade into the pie themselves, and the whole thing made a lovely media event, hitting the nightly news on all three networks.

"The whole idea of sitting around a living room dreaming up something crazy like that to do and then actually having a group of people to go do it with, that was great," Fennelly remembers. It was a heady time: they were Rol?in Hood and his merry band, with Carol as Maid Marian.

If there is such a thing as perfect pitch in handling the media, Snyder had it. In the first winter of Reagan's presidency, Snyder dreamed up the idea of re-creating the poignant "Hooverville" encampments of homeless people that dotted the American landscape during the Great Depression. The CCNV pitched tents across the street from the White House, and dubbed their tent city "Reaganville." Sure enough, it became a regular stopping place for reporters looking for an angle on such news stories as Nancy Reagan's new china.

Snyder, as Fennelly put it, "was the master of the twenty-second sound bite." He deliberately made himself the focus of the cause, and through his personality he gave the homeless movement, inherently invisible and untouchable, a kind of swagger and style. Although he once said that "anyone who works for money is stark raving mad, because prostitution is bad," he got an agent and hit the lecture circuit, bringing in $100,000 a year and more— money he immediately turned over to the community treasurer, Mary Ellen Hombs.

Snyder's obsessive drive would most dramatically show itself in a form of protest that became his weapon of choice in his war with authority, the fast. He learned about the tactic in prison, from the Berrigans, but, as Phil Berrigan says, not entirely approvingly, "he went beyond anything we ever used in fasting." A Snyder fast, like everything else he did, was not a polite protest, but a taunting threat to his target: Say no, and I'll die. The press attention that Snyder commanded made it hard to say no.

He undertook more than a dozen fasts, not all of which were successful. In 1978 he took on Holy Trinity Church, a fashionable liberal parish in Georgetown whose congregation included Roger Mudd, Joe Califano, and the wife of Senator Ernest Hollings, among others. Snyder wanted Holy Trinity to spend some of its considerable funds on shelters; Holy Trinity wanted to make badly needed repairs. Snyder went on a fast without food or water, the sort of hunger strike that usually kills in less than three weeks. Many saw his action as a blatant piece of extortion, and even Phil Berrigan tried to talk him out of it.

"From a nonviolent standpoint, I couldn't justify it, and I told him that flat out," Berrigan says. Snyder would not be moved. By the tenth day of his fast, he was pronounced at the edge of death, but Holy Trinity wouldn't be moved, either. Snyder finally gave up—after the Berrigans had administered last rites.

The failure did not cause him to abandon the tactic, however, and it paid off in 1984, when another fast to near death brought him his single biggest success. This time his target was Ronald Reagan, and the cause was an effort to persuade the federal government to turn over the former college building at Second and D Streets to the CCNV as a permanent shelter that could serve as a model for the nation. Most of the community members, including Fennelly, vehemently opposed the fast: in a presidential-election year the media's eye was likely to be on the campaign.

Snyder prevailed, and although the media did ignore him in the early days of his water-only fast, as summer turned to fall and the election neared, his failing health began to get notice. Moreover, he had a secret weapon: 60 Minutes was filming a segment about him that it planned to broadcast on the Sunday before the election. With the clock ticking, Snyder's slow march toward death became a fullfledged media event: local television reporters gave regular bulletins—"Mitch Snyder's doctor says it's unlikely he'll survive the week." As Snyder faded, Fennelly brought a group of reporters to his deathbed, and for the 60 Minutes cameras he delivered what he thought might be his last public statement.

"The next time you see someone out on the street," Snyder said, his voice husky and weak, "don't pass him by. Say 'Hello,' ask how they're doing, get 'em something hot to drink, get 'em something to eat. Just tell 'em that you care, tell 'em that they're human beings."

Meanwhile, Fennelly went on Nightline and worked furiously behind the scenes, negotiating with Reagan-administration officials. On November 4, the 60 Minutes piece aired, showing Mike Wallace alongside Snyder during a march and comparing him to Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa. That day, aboard Air Force One, President Reagan gave the word: Snyder could have his shelter. It was a dramatic triumph for the homeless, resulting in the nation's largest shelter, which feeds and provides beds and medical care for more than a thousand people every night.

Even as Mitch Snyder was recovering in a hospital bed, Hollywood producers were clamoring for the rights to his life story, which ultimately went to Chuck Fries for the TV movie Samaritan: The Mitch Snyder Story, starring Martin Sheen as Mitch. That deal brought Snyder $150,000 (and, later, trouble from the I.R.S.), as well as entree to Hollywood, which would become a valuable source of funding and exposure for Snyder and the CCNV.

Snyder and Fennelly were fast becoming one of the 1980s' golden couples, with a twist. They mingled with the socially aware set in Hollywood, and with Washington society ladies. Susan Baker, wife of then chief of staff James Baker, became an important ally, and Snyder took a Plexiglas urn bearing the ashes of a homeless man named Freddy, who'd frozen on the streets, to a tea at Barbara Bush's house.

"Mitch and Carol were always real dangerous. I'd read about them and I'd think, Oh, how dangerous, but how thrilling!" says Suzie Goldman, the wife of a wealthy Washingtonian whose family owns a chain of movie theaters. "How thrilling that someone has the courage to do these things that are sometimes.. .well, very odious. But they did them, and I thought, They've got guts."

Joanne Carson, Johnny's ex-wife, went to a talk that Snyder gave in Los Angeles, and decided to become an activist for the homeless herself. "He was very rare in that he put his life on the line, and a lot of people won't do that," she says. "My life will never be the same, and a lot of other people's lives. I can never go back to who I was, there is no way. Never."

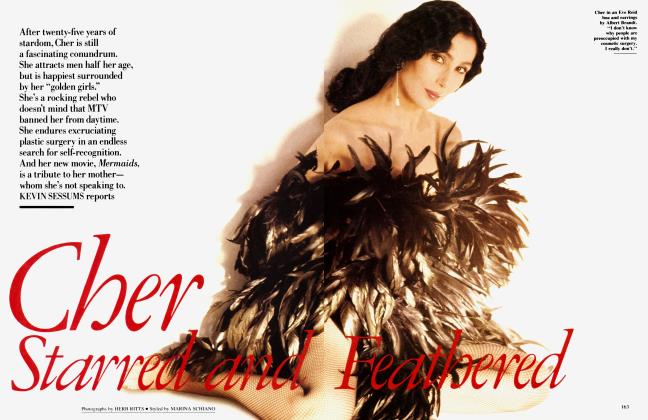

Carson became a personal friend, as did Cher and Martin Sheen and Jon Voight, and homelessness became a chic social cause. Fennelly's elaborate Christmas parties for Washington's homeless became major social events, and the 1987 Christmas bash required the use of two donated fifteen-passenger jets to import all the Hollywood celebrities. Three thousand people attended the event, which featured performances by the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Johnny Rivers, and Dennis Quaid, and dinner served by Cher and Whoopi Goldberg.

Around the Hollywood people, Snyder was a kid transported. Back home in Brooklyn, he'd loved watching old blackand-white movies, and became a sucker for the sentimental Frank Capra vision of one good man prevailing in the end. As an adult, he'd squirrel up in the bedroom and watch his favorite movie, It's a Wonderful Life, sobbing each year at the gooey ending as if it were the first time. The Hollywood stars who wanted to be near him ("a saint," Sheen called him) became a resource for the work, and Snyder loved to march them through the shelter, relishing the shared sense of importance that the celebrities and the wretched of America seemed to bring one another. And yet, he never really "went Hollywood"; Hollywood went Mitch. His trips to the Coast were far rarer than the pilgrimages made by show-business people to the CCNV shelter.

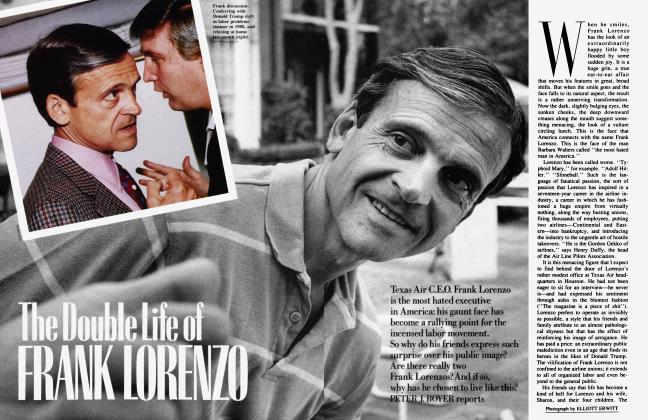

Still, Snyder made a lot of enemies with his confrontational style and refusal to bend. His opponents in government didn't much care for being forced into good works: it was somehow less rewarding to give to the poor if you were having to do it at the end of a gun, or one of Mitch Snyder's fasts. Factions in the D.C. city government bore a particular grudge, and would one day take revenge on him.

Within the movement itself, Snyder engendered mixed emotions. It wasn't easy to be one of the homeless advocates who weren't Mitch. After years of quietly toiling among the untouchables, they saw Snyder not only winning splashy battles they didn't always agree with, but also getting (and accepting) credit for progress many felt was the fruit of seeds sown away from the spotlight. A measure of just how deep such resentments ran could be seen in the days after Snyder's death, when the press was wondering what would become of the homeless movement. Many advocates seemed just a little too eager to say that the movement would do just fine without Snyder. "Mitch had a place and a role to play," one activist told The Washington Post, "but perhaps his absence will give room and space for others to get some attention."

Daniel Berrigan would say that Mitch "had that extra ability of keeping you from hating him," but that wasn't to say he was easy to like, either. One member of the community went a year without speaking to Mitch. Even though the CCNV was ostensibly a democracy, Mitch's natural way of taking charge made it seem more like a dictatorship to some; he had a way of posing an issue so that any position other than the one he espoused appeared patently foolish, which he would then happily demonstrate in community debate, or, rather, monologue, because any debate involving Snyder was a terrible mismatch.

There was the time, for example, when Snyder decided that a fast was needed to force the Reagan administration's hand on making the Second and D shelter permanent. The community was tired, its energies sapped from a long hot summer of shelter work, and many were against it. Some believed that Snyder's reflexive urge to confront was not in the Christian spirit of relying upon God's grace, and one woman, Barbara Weist, said that she felt that achieving the world's largest shelter wasn't necessarily the right course, that smaller shelters were more manageable and more humane. "Fine," Snyder barked. "What would you recommend? Choose twenty of our favorite people and set up an intimate little shelter somewhere? ... We've got one thousand people counting on our place as their home."

Another member meekly suggested that, given the weary state of community workers, a fast just then might not work. "You're not sure it would work!" Snyder screamed. "Since when do we sit around here and plan what is feasible? We're going to discern the right thing to do, and then do it"—which was to say that Snyder had discerned the right thing to do, and they were going to do it. If not, he threatened, he would quit the community: "My conscience wouldn't allow me to do anything else."

It was vintage Snyder, equal parts conviction, intimidation, and arrogance. In the end, as usual, he prevailed, and was proved right—which made for the sort of resentment that had staying power.

For all of this, though, few among Snyder's detractors could credibly doubt his sincerity, or his devotion to the cause. It was up to God to judge his motivations, he would say, let people judge his actions, and by that standard he was beyond reproach. He lived with the homeless, embraced them, and slept on grates with them. He had no assets, and didn't own a winter coat. He laid his life on the line for people who sometimes weren't so sure themselves that they were worth the gesture. "I think he loved the poor in a way that I've never seen them loved by any other person," says Phil Berrigan.

Mary Ellen Hombs, who'd once loved Snyder and worked with him for fifteen years, interpreted his relentless drive as a kind of penance: "Mitch believes he owes," she said, adding that he was driven "to make up for everything he's ever done to anybody." Hombs spoke for herself, and for Carol, and for Ellen Kleiman back in Brooklyn, and for the two kids that Snyder abandoned when he went off chasing his demons.

And if it was indeed remorse that drove Mitch Snyder, then his mission was fired by a kind of self-renewing fuel—remorse was a natural by-product of Snyder's darker side.

In the fluttering moments of Mitch and Carol's first days together, he had shown real passion. When Fennelly went off to California to give him and Mary Ellen room to resolve whatever was left between them, Snyder behaved like a storybook paramour, writing love letters, pleading for her return. But almost from the moment she came back to him, Snyder changed completely, becoming remote, distant, aloof. Carol would later count it as guilt over breaking Mary Ellen Hombs's heart. But if it was guilt, it was a full, deep reservoir, enough to last for the next thirteen years.

Where he'd once behaved like a schoolboy with a crush, holding Carol's hand, walking with his arm locked in hers, such gestures of tenderness vanished utterly. That fetching way with words became a wicked tool of abuse. The humiliations were often public: at a demonstration outside the White House, a perceived misstep by Carol touched off a flood of vile abuse that was witnessed by dozens of people.

At first Carol thought of leaving, but there was still that Mitch Snyder allure; he held a powerful appeal for the opposite sex, and although he once told a reporter, "I don't know what anyone sees in me," in fact, he delighted in the attentions of women. They felt his magnetism, and Carol Fennelly was no different, except that she actually had Mitch Snyder. Her friends wondered why she stayed with him through the years, and she would wonder, too. "Part of it, the larger part, was that I loved him so much," she says, looking back. "There was a magic that happened in our relationship that never went away."

And Fennelly had, as had Mary Ellen Hombs and Ellen Kleiman and Beatrice Snyder before her, a deeply felt urge to protect and care for Mitch. "There was a sense of mission that I couldn't explain to anybody," she says, "even now." She was a first-rate organizer and an able spokeswoman for the shelter, but her first job, her calling, was Mitch.

After the CCNV opened the shelter at Second and D, Snyder moved in there and Fennelly and her kids moved to a CCNV house on Emerson Street. Snyder would come home to her every Saturday night, and go back to the shelter Monday morning. Friends say that Carol was like a mother to him, feeding him, tending to his health, preparing him for his frequent trips. She would drive him to the airport, park the car, check him in, and then stand in the waiting area until he had disappeared into the plane. "She would get dressed up every time he came back into town," says Suzie Goldman. "We'd go through my closet, or she'd go through the box room, where the donated stuff is, and she'd find something that was fetching, and she would try to look like a bride."

As for a social life, there wasn't much. Suzie's husband gave them a pass for his theaters, and they would see an occasional movie, but mostly Snyder liked to watch TV ("the silliest sitcoms," Carol remembers). Restaurants were out of the question. "Mitch was very painfully conscious of his image, and he didn't feel comfortable being seen in restaurants," Carol says. He really enjoyed only one place—a funky Mexican-Salvadoran place in the Adams Morgan district called El Tamarindo. "Even if somebody else was paying for the meal, he was so visible that he didn't go many places.

"The normal things that most couples do—like eat dinner together, or go shopping together—were abnormal things for us. And so, going shopping was a ritual that we did. Once a week we went shopping. ... [But] just stepping outside these doors, when we were grocery shopping, everybody wanted to know what was in our shopping cart."

Fennelly craved time away from the work, and devoured the small fragments of "normal life" that she was able to snatch up. She and Suzie Goldman became best friends, and Suzie and other friends would sometimes "kidnap" her, let her roam through their closets for something stylish, and then go out for a night on the town. "I love to go to my friends Duke and Linda's house and eat crabs and drink champagne," she says. "They have a beautiful home in Rock Creek Park, and it's totally bourgeois, and I don't care. So, yes, I do normal things. Mitch didn't, however. And that was a real tension between us."

There would come a day, after Snyder was dead, when Fennelly would resent their constricted life together: "That's the one point of anger that I feel, is that we didn't do more things together, you know?"

After a fast or a long organizing trip, Snyder would go home to Fennelly and stay at the Emerson Street house with her and the kids for as long as a month. She would invariably plead with him to remain, and he would invariably leave— whereupon Fennelly would ritualistically rearrange the bedroom furniture to "get rid of the happiness."

If Snyder's heart was wholly open to the homeless, the other side of that generosity was a near-complete inability to show love to those who were closest to him. "Mitch was very good at loving in the abstract, and not very good at loving his neighbor down the hall," Carol says, and Mary Ellen Hombs would use almost the same phrase. Snyder held the deep conviction that to truly follow a holy calling a man had to give himself wholly, exclusively, to it; it was the vision of Gandhi, whom Mitch studied ferociously, and, for that matter, it was the practice of Jesus too. In that Gospel of Matthew, which had been Snyder's primer for his new life, Mary and Jesus's brothers come to see Him, and He turns from them, saying that those who do the work of God are His true family, and then leaves to go preach to the multitudes. That was an attitude Mitch could relate to.

But Snyder's distance was more ominous; it was an inner rage that sometimes erupted in vicious torrents of verbal abuse— and occasionally something worse. "He had a very, very stormy, and rocky, and sometimes violent relationship with Carol Fennelly," Phil Berrigan says, "and that seemed kind of out of control, on both their sides. I think that if he were alive today he would admit that."

Carol had a hair-trigger temper, too, and their epic ragings could send chills down the spines of those who witnessed them. "He had a lotta rage inside him that he hadn't dealt with," says one CCNV member, "and so he struggled with that by being a peaceful person, and most of the time he was. And the most you'd ever see [of the violence] is if you got in an argument with him he'd just go off. He wouldn't go off physically [with other CCNV members]—he did with Carol occasionally, but it was very seldom. And Carol, you know, is the same way. So they were sort of fascinated with each other's potential violence."

In one particularly nasty fight at the shelter, Fennelly stormed out and Snyder stormed right out after her. As she got in her car to drive away, Snyder lay down in the alley, to block her path, and she kept right on going, grazing his arm. "It came to be like a TV show," one community member says. "It was like a TV drama, or a soap opera playing in the background."

At one point, Carol sought counseling and discussed the abuse, and her friends urged her to leave the relationship. "I did all the time," Suzie Goldman says. "I said, 'It's just not worth it—nothing is worth the anguish.' But there was just this dogged, stubborn determination to stay there, and to accept. She tried to rationalize why he was, he could be, very abusive. I don't think he meant to be abusive. I think he just never forgave himself for leaving his first family."

The Mitch-and-Carol brawls became so common that community members at the CCNV almost stopped noticing them. But through all of it, there was always the work, and in that Snyder and Fennelly were the perfect couple. To them, it was a bond forged by God, and it was the fire that heated their passion.

Mitch Snyder's decline was swift and steep, and it began at the moment when his life with Carol seemed to hold the most promise. Last fall, after a huge rally for the homeless in Washington, Carol moved into Mitch's rooms at the shelter. Her younger child was out of school, and they were free to be together, more or less alone, for the first time. They had excitedly planned for the moment, and Carol had even talked with a doctor about the possibility of having a baby.

The "Housing Now!" demonstration had been a success, but it was devastating for Snyder personally. All the simmering resentments within the movement, built over the years of Snyder's growing legend, came to the surface. He'd spent a year on the road, organizing, sometimes hitting two or three cities a day, and by the time of the rally he was worn down, feeling like an unwelcome presence. Although the number of speakers at the event was being kept to a minimum, Snyder was to have spoken twice, a decision that some of the organizers saw as yet another exercise in Mitch worship. Snyder picked up on these feelings, and reacted predictably, saying that he wouldn't speak at all.

"He was barred from the homeless march," recalls Marsh Ward. "They barred him! Mitch Snyder! There's 300,000 people out there, certainly there because of what he had done, years and years of his efforts, and there was the greatest march we've ever had for the homeless and they wouldn't let him into the stage area. ... Not to include him in the end, I mean, that was a violent act itself. ' '

Fennelly says that Snyder wasn't actually barred, that he'd removed himself from the roster of speakers, but in either case the event was a blow. "One of Mitch's great pains in the end was that a lot of the organizers, particularly East Coast organizers, mostly men, turned on him. And everything that went wrong they blamed on Mitch."

Months later, Snyder would deepen the alienation by actively opposing participation in the 1990 census, on the ground that it was ineffectively conducted and that the homeless would be underrepresented. His position outraged others in the movement who had fought to have the homeless counted in the first place. Some advocates spoke of the growing backlash against the homeless movement, and publicly implied that Snyder was partly to blame. One told The Washington Post that she'd gotten a call from a city-council member, who said, "You'd better disassociate from Mitch. Your movement really needs some leadership now."

The long-festering resentments inside Snyder's own CCNV community began to show themselves as well. There was a feeling in some quarters that Snyder's priorities didn't take into consideration the real problems the CCNV faced now that it was running a shelter, such as dealing with a rampant drug problem in the facility. Snyder had always felt that the CCNV wasn't a police force, that it was there to provide shelter to whoever needed it, even drug users, but the community summarily overturned his policy. It also lost patience with Snyder's wrangling over old philosophical disputes with some of the older CCNV members, and finally he was asked to move aside during community meetings; he was deeply wounded. "He said to me at one point, this would be maybe three months before his death, he said, 'Now they're all turning against me,' and he was becoming a scapegoat," Phil Berrigan recalls. "They were all blaming him for the shortcomings of the life here, or the pressures from without, or the lack of support. And a lot of that is unjust."

Snyder had changed, something had gone out of him, and the old chemistries that had ruled his relationships with people were suddenly rearranged. It was at this moment that Fennelly found the will to leave him.

Fennelly, too, was weary from her work on the "Housing Now!" campaign, and decided to take a year off from political organizing. The shelter's basement infirmary was in turmoil, partly because of the drug problem, and so she moved into rooms down there, to straighten things out and to get acclimated to life in the shelter. She asked Mitch to move with her, it was relatively quiet and secluded down there, but he refused. He began to feel isolated, and to further isolate himself. With Carol living in the shelter, there was no longer a place for him to go for relief and rest.

Within weeks, the strain began to erode their relationship. Snyder not only wouldn't move in with Fennelly, for three weeks he wouldn't journey the three flights downstairs for a visit, prompting more battles. In November, Carol told Mitch they were finished. Such threats were not new, from either side, but this time there was a factor that made the split real: she had met someone else, a respected jazz musician kicking a thirty-year drug habit.

This new man was in every respect Mitch Snyder's opposite: soft-spoken and calm where Snyder was tempestuous, able to express affection where Snyder was not. Carol met him early one day, while he was saying his morning prayers, and they fell easily into a relationship.

Mitch noticed. Increasingly removed from his work, he now turned his obsessive focus on Carol. It wasn't just attention; it was a relentless, singular force. It would become his last campaign.

Though he never confronted the jazz musician, he lobbied Fennelly ceaselessly for a reconciliation and started to talk about marriage. But Carol was quite happy in her new relationship. "She didn't have the weight of the world on her shoulders," says a friend. "She learned to laugh and do silly girl things, and to enjoy the moment, and to enjoy simplicity, and to enjoy quiet.... I think that, after what she'd been through for so many years, that kind of a friendship was very, very appealing to her."

Snyder's deteriorating state was becoming plain to everyone; his anguish and fatigue were evident in the drawn lines in his face, the weighty bags beneath his eyes. He was a desperate man, and in January he undertook a desperate act. He began a fast to win Carol back.

For forty days he starved himself, taking only water in a kind of grim, mad parody of the fasts that had once seemed so noble. Carol, frightened and put off by the gesture, left the shelter, and refused to come back until he ended the fast, which at last he did.

Then, in March, the D.C. council voted budget cutbacks that would severely hit the shelter programs, and Snyder went on a ten-day fast to stop the move. It was one of the total fasts, the quick killers, like the one he'd used against Trinity, and it was clear that Snyder did not necessarily want to survive it. He wrote a letter to Carol threatening to end his life if a reconciliation could not be had.

Not only did the council ignore his fast, but it threatened to gut Initiative 17—a kind of homeless Bill of Rights guaranteeing shelter to all homeless people in the city, which Snyder and the CCNV had won in 1984. It was an uncanny series of bleak events, and just when it seemed that Snyder might be consumed by them, Carol returned to him.

In April she'd gone to the Soviet Union on what she thought would be a tour of soup kitchens there, as part of a church group. The trip had turned out to be a lot more grueling—it featured such grim moments as a tour of Soviet mental hospitals—and suddenly Carol had an awakening. "I understood, in a kind of flash, that for me to be who I am, that that part of my life needed to have that vision and purpose, including my relationships. That there would probably never be a relationship like I had with Mitch, that it had that purpose and vision that we shared, and it made sudden imminent sense that I should marry him and come back to him."

She called him when she got to Kiev, and gave him the news. He seemed happy. When she returned to Washington, Snyder announced their engagement. "I came home with absolute hope," she says now. "I would have married him the day I came home." She brought him a present, a pair of Russian baby booties. They set September 9 as the wedding date, and Carol moved from the infirmary up to Mitch's rooms.

But matters didn't improve. Even as he wearily geared up for another battle, Snyder despaired over the council's plans to gut Initiative 17. In May he called his old friend Steve O'Neil, a political organizer who'd helped with the first campaign. "He was really down about this thing," O'Neil recalls. "You can imagine—I mean, we're doing the work over again that we did six years ago. We're fighting for shelters when we should be fighting for permanent housing. I think that was a real depressing thing for him."

When Snyder announced that he was going to take a month off for a stay in a Trappist monastery in Virginia, everyone encouraged him, but he kept delaying the trip. "Knowing Mitch, just to think that he would even think about doing that, seriously, going away for thirty days, which is a lot of time, to me meant that there was something very seriously wrong, and that he realized it," says O'Neil. "But he kept putting it off, because there was always some other issue, some other crisis, like this initiative."

Marsh Ward tried to talk Snyder into going. "The last conversation that I had with Mitch was exactly that," he says. "He was saying to me, 'I just hurt all the time,' and I said, 'Mitch, you gotta let go.' And he said, 'I don't know how to let go.' And I said, 'You gotta get away, go to the monastery.' And he nailed me. I'll never forget the look on his face, because it wasn't anger, it was just real sad. He said, 'You know about the proposition campaign and you know what'll happen if we lose that.' I said I knew. He said, 'I want to ask you if we have a chance of passing it if I'm not here.' And I couldn't tell him yeah, because I didn't believe it."

He did get away for a few days, a quick trip back to Brooklyn, to visit his mother and sister. Bea Snyder could see that "he was going nutty.... Usually, if he didn't get his way, he would ordinarily have gone on a fast. He couldn't do that anymore. ... He knew he couldn't go on fighting anymore—it wasn't in him. Don't you see? He had to give up. His only way was to give up."

On his return to Washington, the I.R.S. informed Snyder that he owed the government $90,000 in taxes and penalties based on his earnings from the TV movie— earnings that he had turned over directly to the CCNV. And despite the marriage plans, Mitch's relationship with Carol was no calmer. She had refused to stop seeing the jazz musician, saying she was concerned, as a friend, about his fragile state of recovery. Mitch said he understood, but it was clear that he didn't accept it. He was a different person, suddenly clingy and clutching; the rages erupted anew. He accused Carol of agreeing to marry him as a cruel hoax, to repay him for the years of pain she'd felt, and in one outbreak he threatened to throw her things out the window of their third-floor room.

"Carol and I talked the week before [Mitch died], and she told me how much she loved him," Suzie Goldman recalls. "She said, 'Why couldn't it be normal? Why was he so insane? Why didn't he believe in my love?' There was this desperation."

The weekend before the Fourth of July, Snyder and Fennelly would have their last, most desperate flare-up. Carol spent that Saturday away from the shelter, cleaning up the Emerson Street house in advance of another CCNV staffer's moving in. When she returned, Snyder was not in their rooms. The next morning, he came in, angrily accusing her of being with the jazz musician, ignoring her protests to the contrary. She left, and went to the musician's apartment, intending to return to Snyder Sunday night.

But when the moment came, she couldn't go back; the calm and quiet of this new sanctuary held her.

On Monday morning, she returned to Mitch, stopping outside the shelter to throw up. Then, inside, Mitch succumbed to a horrible rage, a violent pain that literally transformed his features before Carol's eyes. She told him she was leaving for good, and as she entered the elevator she heard him shout, "I never want to see you again."

It was the last thing Mitch ever said to her.

Carol would later learn that Mitch spent the rest of that day and all of the next waiting by the phone. She didn't call. Sometime Tuesday evening, Snyder methodically went about the business of ending his life.

He went to the third-floor utility closet and grabbed one of the yellow extension cords that the shelter staff used with the heavy-duty vacuum cleaners, then returned to his rooms and locked the doors. He had a bottle of whiskey, and drank some, but he didn't get drunk (the autopsy showed a blood alcohol level of .07). He moved all of Carol's things from their bedroom into the adjoining office. He took out a pen and a yellow legal pad, and wrote her a letter:

"Dear Carol, I loved you an awful lot. All I ever wanted was for you to love me more than anyone else in the world. Sorry for all the pain I caused you in the last thirteen years. Love, Mitch."

He added a P.S., which would later suggest that he was in complete control at the end. The postscript told Carol where he'd hidden $8,000 that he'd been saving for a year-end organizing campaign; part of it was in the pocket of his fatigue jacket, which was hanging in the closet, and part was buried in the soil of a potted plant. He sealed the note in an envelope, placed it on a credenza near the door, and then flung the cord over a heating pipe near the ceiling. He stood on a chair, wrapped the cord around his neck, and stepped off.

Carol Fennelly had always had the urge to take care of Mitch Snyder, she'd seen it as her special mission in life, and so it would be in death. When it came to the final caring for Snyder, she would tend to it herself.

After the coroner's examination, Snyder's body was sent to the Rapp Funeral Services home, where Carol and Snyder had one last moment alone. She held Mitch in her arms, and wiped away a tear that appeared in one of his eyes. He looked so tired and haggard that she applied makeup to his face to return the color.

She put a videotape of It's a Wonderful Life in the casket with him. And then she helped to place Snyder's body in the crematorium. They knew her at the funeral home—she and Snyder had been there so many times with the unclaimed bodies of the homeless that Snyder loved—and so her last, unusual request was honored.

After the body was placed in the crematorium, Carol reached up and turned the knob herself, returning Mitch Snyder to ashes.

This summer, seven weeks after Snyder's death, Carol Fennelly asked a Washington probate court to declare her Mitch Snyder's legal wife. The case is pending. Fennelly says she took the action because "I don't want to go through life being called 'Mitch Snyder's longtime companion.' "

There is another reason, a legacy of that old insecurity she'd carried for so long regarding the other woman in Snyder's life, Mary Ellen Hombs. Snyder left a will, which he'd written before that long, ultimately successful 1984 fast to win the shelter, naming Fennelly and Hombs as the co-trustees of his estate. It is a meager estate (he left nothing but a bag of used clothes and his corpse), but if Carol wants to negotiate a book or movie deal, or otherwise employ Snyder's name, she may have to share the decision with Hombs.

Fennelly has, after some dissent, inherited Snyder's mantle of leadership at the CCNV, acting as chief spokesperson and organizer in the campaign to reinstate Initiative 17. The first phase of that campaign, getting enough voter signatures to qualify the measure for the ballot, was a solid success. The petitions were due on August 14, Mitch's birthday, and she turned the occasion (just a month after Snyder's suicide) into a media event, with a march down Pennsylvania Avenue and a demonstration on the steps of the District building. But Fennelly says her leadership role is strictly temporary: "I don't ever want to be in the position that Mitch found himself in on July 3, when he knew he needed to get out of here, but felt that he absolutely couldn't."

In a sense, Carol Fennelly is now free to pursue a normal life, but she vows, "I will always do this work."

There are times, as she lives each day in Snyder's room, when she mulls her role in Snyder's suicide, and asks herself what she should have done. "If I'd only put my arms around him and held him that last day," she says, with tears coming, "he would still be alive."

She also wonders what will become of the rest of her life. "Forty-one isn't ancient, I realize, but at the same time it's not twenty either. My kids are grown, so I have a degree of freedom. But look at who I am. I'm what they call a strong woman. . . . And so I'm having to deal with the very real possibility that I'll have to live the rest of my life as a single woman. . . . How many men are going to put up with a woman who goes to jail and dies for what she believes in?"

Joanne Carson, who gave a memorial service for Mitch in Los Angeles and put Carol up for a brief rest (in the room where Truman Capote once took sanctuary), believes that Fennelly will endure, and prevail. "They were like a rocket," Carson says. "Mitch was the booster, the fire, and Carol is the second stage."

But Suzie Goldman isn't so sure.

"She is his now, forever," says Carol's friend. "I think that he has her now, for ever and ever and ever. He knew that that was the way to ensure her fidelity for the rest of her life, that there will be no one else in her life. And I don't believe there will be."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now