Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBURYING THE JESUITS

PHILIP BENNETT

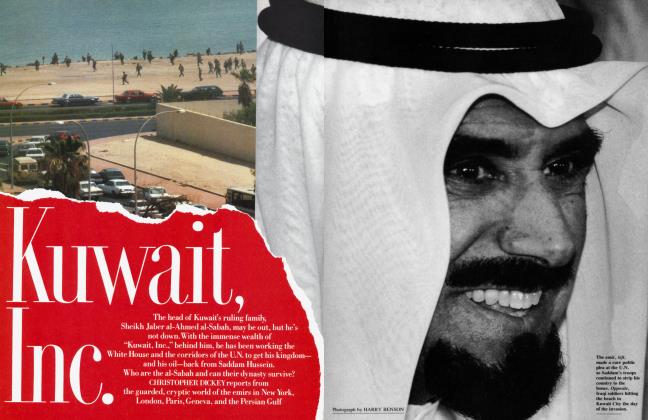

The Salvadoran high command has been implicated in the vicious murder—one year ago—of six outspoken Jesuits. So why is the U.S.-backed investigation going nowhere?

Letter from El Salvador

As he was led out to be executed, Father Ignacio Martm-Baro raised his voice into the blackness, above the indifferent orders of soldiers, and shouted, "This is an injustice!" The phrase was one he had issued countless times in recent years, usually with the force, like now, not of an appeal but a judgment. Martm-Baro and other Jesuits at the University of Central America often used words the way their enemies reached for guns. The defiant, cool authority of their voices gave the next morning a special horror, as a crowd formed over the bodies. The priests were face down on the lawn, their heads blown open. Blood made the grass as slippery as after a rainstorm, and people began to gasp in the gathering heat. But pressing down on the scene, unforgettably, was an extraordinary, appalling silence.

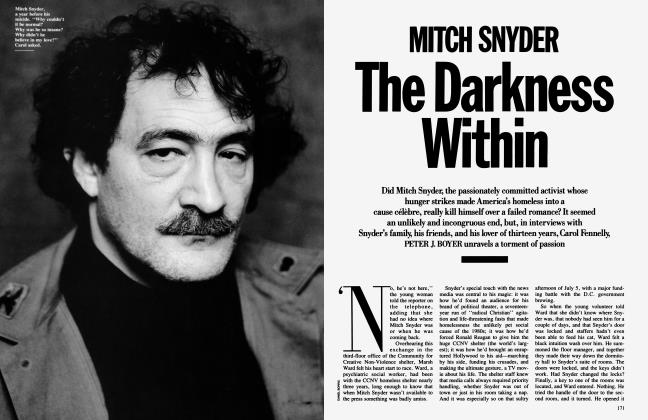

'Killing them wasn't enough. The point is to bury them forever," a priest said on my first day back in El Salvador, almost a year later. Officially, the murder last November of six Jesuits, their cook, and her daughter remains a mystery. Eight Salvadoran soldiers, including a colonel, have been arrested and may or may not someday face trial. But the details of what really happened that night and in following weeks have been hidden inside the U.S.-backed military. The unanswered questions about the murders have placed the United States in its most awkward position since American involvement in the civil war between the Salvadoran government and leftist guerrillas stopped being a front-page story a few years ago. It appears that some U.S. officials, while vowing to see the case solved, have become entangled in the cover-up, more than once crossing the line dividing support from complicity.

The U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, William Walker, who keeps a photograph of the most prominent of the slain Jesuits, Ignacio Ellacuria, on a wall of his office, said the morning after the murders, his voice shaking with emotion, "I can't imagine what kind of animals could kill six priests and two women in cold blood." In the end it required little imagination at all. They were, it would seem, our animals. The soldiers who later confessed to pulling the trigger were elite troops praised by U.S. advisers as among the Salvadoran army's best. Their superiors, whose alleged role in covering up the crime has cast doubt on assertions that they had no prior knowledge of the murders, are the prodigies of U.S. policy, commended as politic and professional. They are men whom Ambassador Walker, for example, would invite into his home to celebrate the Fourth of July.

At this year's Independence Day party, bodyguards munched on fried chicken in the driveway, and a Dixieland band played by the pool. On the waxed patio, laughing over cocktails, were the same Salvadoran officers and politicians who, in private, were under pressure from the embassy to come clean on the murders. But how much pressure? And how clean? These were also the faces of a multibillion-dollar U.S. foreign policy, a ten-year investment now in jeopardy. Surveying the crowd, it was easy to see why one military guest, when asked later to describe the stakes in the Jesuit case, replied simply, "Everything." It was a view I would hear expressed a number of ways. Just after the Walkers' young son released a dove of peace into the seamless afternoon, I ran into a right-wing businessman who was an old friend. "Iam not threatening you," he told me later in his office, taking my arm. "But if you get to the bottom of this, you know where you'll end up."

It was hardly clear at the time, but the Jesuits now appear to have been doomed from the moment they decided to stay on the sloping campus of their university, the UCA, and wait out the largest rebel offensive of the war. On Saturday night, November 11, 1989, fighting by the leftist Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, or F.M.L.N., erupted across San Salvador. Leftist politicians went into hiding as government radio demanded their heads and that of the university's rector, Father Ellacuria.

The military had known an offensive was coming, but misjudged its scope. Reinforcements were rushed to the capital. Among them was the commando unit of the elite Atlacatl Battalion, which is famous for some of the toughest combat and worst human-rights abuses of the war. The commando unit's leader, Jose Espinoza, was a veteran of U.S. Special Forces training at both Fort Benning and Fort Bragg, and, though a twenty-eightyear-old lieutenant, a star to some U.S. officials. In fact, on the day the offensive began, his unit was undergoing training by a team of U.S. Green Berets.

Arriving in the capital late Monday, Lieutenant Espinoza's commando unit reported to Colonel Guillermo Benavides, director of the Salvadoran Military School. Troops at the academy were defending an area including army headquarters, Ambassador Walker's home, and the UCA. Almost at once, Lieutenant Espinoza was sent to search the priests' campus residence, where, the army said, there had been rebel gunfire. The search order came from the highest authority— it was signed by President Alfredo Cristiani and delivered by Colonel Rene Emilio Ponce, then the armed forces' chief of staff—but it must have caused a shudder in Lieutenant Espinoza. A few years before, he had graduated from the Jesuits' prep school. Father Segundo Montes, a human-rights expert who lived at the UCA and would die there two nights later, had been the school's principal.

Colleagues of the priests' now believe that the search, which turned up nothing, was a dress rehearsal. Catholic Church leaders have accused the military of drawing up a master list of perhaps a hundred religious and political figures who were to be eliminated. But no hard evidence has emerged to link Cristiani's order to the killings. In fact, rather than cause alarm, the search reassured Father Ellacuria, who had returned that day from accepting a human-rights award in his native Spain. (He became a Salvadoran citizen after arriving in the country in 1948 as an eighteen-year-old novice.) Ellacuria even argued to friends that the army would never show its hand before committing a murder. "Ignacio was Cartesian, with absolute faith in logic," says his friend Ruben Zamora. "This time his analysis failed him."

The soldiers who later confessed to pulling the trigger were elite troops praised by U.S. advisers as among the Salvadoran army's best.

While Ellacuria breathed easier, military leaders were going over the edge. By Wednesday, the fourth full day of the offensive, the rebels had dug into dense urban neighborhoods. The army was being shot to pieces; there were rumors of

new assaults and fears of a general uprising. A handful of U.S. advisers had taken to sleeping nervously at the high command. On Wednesday night, twenty top Salvadoran commanders—including chief of staff Colonel Ponce and Colonel Benavides of the military school—met gravely at the high command. They decided to bomb rebel-held neighborhoods. At the meeting's end, they joined hands in prayer and asked for God's help. Top commanders then briefed President Cristiani until about two A.M.

According to subsequent confessions by soldiers charged with the murders, Colonel Benavides emerged from the high command near midnight determined that the Jesuits would die. He summoned Espinoza and two other lieutenants into his private office at the military school. According to Espinoza's subsequent confession, Colonel Benavides said, "This is a situation where it's them or us. We'll begin with the leaders. In our sector we have the university, and Ellacuria is there." He turned to Espinoza. "You did the search and your people know that place.... He must be eliminated and I don't want witnesses." Espinoza said he protested, but feared being accused of treason. He assembled his troops. But before departing, he did one more thing: he borrowed a bar of camouflage soap, to hide his face from the victims.

The trip from the military school to the UCA campus takes about five minutes, but the distance between the worlds they represent spans one of El Salvador's deepest chasms. For twentyfive years the schools have produced competing elites. The military school, known as "the School of Presidents" for a long line of dictators, has hammered out a caste of officers who generally regard change as a malevolent virus. The UCA, meanwhile, became a laboratory of change. Martm-Baro, the vicerector, joked about the price of an intellectual assault on the status quo, telling visitors, "Here, it's publish and perish." But the faculty was serious about being soldiers of Christ, on the side of the poor—to the point where after the massacre, when asked what he felt seeing the mutilated bodies, one Jesuit replied, "Envy."

The Jesuits and the reigning officer clique, members of the military school's class of 1966 known collectively as the Tandona, were natural enemies. As a military brotherhood, the Tandona was heir to a tradition of hatred of the church that in the early 1980s resulted in a bloody crusade against all orders of clergy. But ascending the military ranks during the war, the Tandona had ambitions of greater sophistication. While loyal to murderous members, the class also mastered the impersonal language of U.S. counterinsurgency policy. Under Colonel Ponce—a shrewd tactician with a deceptively shy manner, who graduated first in his class and remained its leader—the Tandona amassed corporate political power.

Father Ellacuria, in particular, challenged it. Pushing for a negotiated peace—and adamantly opposing U.S. military aid—he started meeting regular-ly with President Cristiani after Cristiani's inauguration in June 1989. Ellacurfa became the principal bridge between the rightist president and the leftist guerrillas, many of whom he had known for years. And as his authority grew, senior army officers screamed that Ellacurfa was himself a rebel commander. Colonel Juan Orlando Zepeda, the current vice-minister of defense and the Tandona's chief ideologue and intelligence guru, called the UCA "a refuge for terrorist leaders."

These remain unashamed opinions, despite the military's efforts to distance itself from the killings. "The Jesuits were powerful allies of the F.M.L.N.," Major Roberto Molina, the head of the army's new human-rights program, told me recently. "Our society has reached levels of moral degradation, and the great cause of this is the Catholic Church. They promote hate and class struggle. What is the root of our problems? Is it the armed forces or priests who ignore their pastoral mission?" Who did Major Molina think killed the Jesuits? He lowered his voice. "Foreigners, dark forces of the United States bent on breaking the armed forces as an institution. It was the trilateral commission, the society of the skull, groups where just to mention their names risks your life."

Ponce has bluntly defied the Bush administration, transferring one key officer out of the country. "He's telling us, basically, to fuck off.

Colonel Benavides, a Tandona member, is the only officer to have been charged with ordering the murders. Colonel Ponce and other senior officers, who refused to discuss the case on the record for this article, all say they learned of the army's role only early this year. "It's all speculation," Colonel Zepeda says of the high command's involvement. But the speculation is widespread, even within the military. When I asked if it was possible that as the army's chief of staff Colonel Ponce didn't immediately learn the identity of the killers, General Adolfo Blandon, Ponce's predecessor, replied, "If he didn't, then who's in charge?" Asked if Colonel Benavides could have made a decision of such magnitude alone, Blandon said, "If one follows rules of discipline and order, then Benavides couldn't have acted alone."

What is certain is that when Lieutenant Espinoza and his men set out in the middle of the night to kill the Jesuits, they did little to conceal their operation. Soldiers left a crude sign claiming responsibility for the F.M.L.N. But Espinoza's unit—some fifty uniformed men—arrived in an area patrolled during curfew by scores of other troops. After the murders, they staged a thunderous battle, firing heavy machine guns, an anti-tank weapon, and a flare that lit up the sky over the blacked-out capital.

According to the confessions of several soldiers, the whole thing had taken about an hour. The troops scaled a back fence of the campus. They banged on the windows of the residence until Martm-Baro and another priest unlocked the doors. A sergeant, a Fort Benning graduate who used the nickname Satan, forced-five of the priests to lie face down n on a grassy knoll outside the > building. He then approached Espinoza, who said, "At what time are you going to proceed?" Considering this an order, the sergeant returned to the priests with his M16 and told another soldier, "Let's proceed." They started shooting, one by one, aiming for the heads.

A few yards away, a soldier shot the Jesuits' cook, Elba Ramos, and her fifteen-year-old daughter, Celina, who were embracing in a guest room. A sixth priest appeared in a doorway and was also shot. He grabbed the leg of a soldier, who turned and finished him.

Espinoza said that he left the campus in tears, the only known admission of remorse by any military figure connected to the case. He said that he had stormed into Benavides's office back at the military school and told him, "My colonel, I don't like this thing that's been done." Benavides, he said, replied, ''Calm down. Don't worry, you have my support. Trust me." By dawn, Espinoza was ordered to take his commando unit out of the area.

The scene at the UCA the next morning was, for me at least, enough to bum an image of evil forever into one's memory. As can occur in few places but El Salvador, speculation ensued as to whether the intact brains in plain view on the grass had actually been removed by the killers as symbols that these, after all, were the minds behind the rebels. The argument lasted until the U.S. Embassy released a forensic report maintaining that loss of encephalic mass was simply what happened when you got shot in the head at that range with an Ml6.

The bodies had been discovered by a gardener, but I learned recently from a trusted military source that one of the first people to see them was a U.S. official from the C.I.A. He was among a dozen agents working at the military's National Intelligence Directorate, the D.N.I. After the murders were announced at an early briefing—to applause, according to some present—the American and two Salvadoran officers drove to the campus, a few blocks away. The American left quickly when cameras arrived. Back at D.N.I. headquarters, the C.I.A. official said to his Salvadoran counterpart, tersely, ''We believe that the military did this."

It would be nearly two months—not until Colonel Benavides was fingered by an anguished U.S. Army major and arrested—before any U.S. official said the same thing in public.

Inside the U.S. Embassy, an air-conditioned bunker designed to withstand earthquakes and rebel attack, diplomats describe the Jesuit murders as a test case. In El Salvador, this usually means that it is known where the truth lies. What is being tested is whether more than $4 billion in U.S. aid has bought the will to get there. On this count, according to a wide range of critics, not just the Salvadoran army but also the embassy has failed dramatically.

''From the first moment, the embassy worked to minimize the costs of the massacre for the armed forces," says Father Jose Maria Tojeira, the Jesuit provincial for Central America. ''The American Embassy lied, contradicted itself, and even placed people's lives in danger. They have made absolutely no effort to discover anybody above Colonel Benavides. I believe they have in fact blocked these efforts." A senior aide to the late president Jose Napoleon Duarte, a U.S. ally, says, ''The embassy always covers for those it thinks are the good guys. The embassy knows well who's behind the murders."

''That's bullshit," Ambassador Walker says angrily. ' 'The killers of the Jesuits did more harm to U.S. policy in El Salvador and to the armed forces than any damage by the F.M.L.N. However embarrassing the truth is, it's better to get it out in the open." But getting things out in the open has not been the embassy's strength. Walker acknowledges that no embassy personnel, whether from the C.I.A. or elsewhere, were interviewed about the crime, and that, more important, months passed before U.S. officials even asked Colonel Ponce or other army officers what they might know. The most rigorous questions have come not from the State Department but from a dogged congressional task force led by Representative Joe Moakley. Embassy officials, for the most part, have fallen into a well-worn routine of sounding helpless, while directing blame at a plodding, corrupt (U.S.-funded) legal system.

"There are some who believe the case shows the unredeemable evil of the armed forces," says U.S. Ambassador Walker, "and I don't believe that."

Some of this impotence is no doubt genuine. Despite the fact that the United States funds most of the Salvadoran military's budget, the high command has always kept family secrets to itself. Colonel Ponce has bluntly defied the Bush administration by refusing to purge a list of Tandona members described as criminal, incompetent, or both. Meanwhile, he has transferred one Tandona member suspected of having information about the killings—former intelligence chief Colonel Carlos Guzman Aguilar—out of the country. Describing Ponce's attitude, one U.S. source concludes, "He's telling us, basically, to fuck off."

However, despite the anger, U.S. officials are loath to connect Colonel Ponce to the murders. The reason is simple: during the last year, the embassy, fearing more pathological rightists, pushed Ponce as the next minister of defense, a campaign that finally succeeded in September, when he was named to the post. And herein lies the enormous paradox of the Jesuit case for the U.S. government. As with the murder ten years ago of four American church women, the embassy needs the Jesuit case solved as evidence that the Salvadoran government is committed to self-improvement and worthy of financial support. But unlike any previous case, solving the murders—if in fact the high command was involved— or even applying intense pressure to the army could destroy the strongest institution built by a decade of U.S. policy.

Put another way, if the case goes unsolved, the military risks losing U.S. funding; if the case is solved, the military risks losing the war. For some officials in the embassy, either outcome is unacceptable.

The man in El Salvador whom Jesuits today seem to distrust most is an embassy official named Richard Chidester. "No single person has done more to obstruct the investigation," states Father Tojeira. That is an exaggeration, but it reflects the pervasive murkiness that Chidester has come to inhabit. It is a reputation that, self-consciously, even he encourages. "Yeah, I am the Devil," he says when you meet him.

Rick Chidester is one of the U.S. diplomats in Latin America who keep popping up in thankless jobs and losing causes. He was formerly stationed in Honduras as the State Department liaison officer to the Nicaraguan contras. He worked in drug enforcement in Mexico. A friend of Ambassador Walker's, comfortable in gray suits in the tropics, he left his family behind in the States and went to El Salvador last year as the embassy's legal adviser. But his real job since November has been to help run the Jesuit investigation.

He got off to a bad start. A week after the murders, the only civilian eyewitness identified so far, a cleaning woman named Lucia Cema, was spirited out of the country on a French-government jet. At Walker's request, Chidester was also aboard. As the Jesuits understood it, he was to help Cema clear customs in Miami. She had already given sworn testimony about what she had seen and heard while she hid: men in military uniforms, voices of priests, gunshots. It wasn't much, but at the time it was all there was. It pointed to the army.

But, arriving in Miami, Cema was put in a hotel room for a week of F.B.I. interrogation. The only other people present were Rick Chidester and Lieutenant Colonel Manuel Rivas, the Salvadoran military officer in charge of the government's investigation, who was in Miami at Chidester's invitation. Under pressure, Cema became confused, changed her story, and eventually said she saw nothing at all. Back in El Salvador the government, with the embassy's blessing, announced that Cema had been revealed as an unreliable witness. The Catholic Church went berserk.

Chidester denies charges by the church that Cema was "brainwashed" or subjected to "violent interrogation." On the contrary, he argues that the Jesuits had coached her into implicating the military. (Representative Moakley's task force concluded that Cema's original testimony appeared to be accurate.) He says he put her $2,500 hotel bill on his personal credit card, even helped her order from room service. His relationship with Cema was good. "She was begging me not to leave her," he told me. This is not hard to imagine, considering what Cema, a woman fleeing in fear for her life to a strange country, might have felt when she saw Lieutenant Colonel Rivas, an officer from the army she was fleeing, striding into her hotel room. Nothing of the sort, Chidester says. "She was happy to see him.''

It is the nature of Chidester's relationship with Lieutenant Colonel Rivas that most dismays his critics. Chidester is program director of the U.S.-funded Special Investigative Unit, which Rivas directs. They are described as close friends. Despite the investigative unit's lackluster performance in the Jesuit case, often attributed to the fact that its head is an army officer (and one with the nearly impossible task of investigating his superiors), Chidester adamantly defends Rivas. He has even taken to accompanying the chief investigator on his rounds, occasionally leaving the rather odd impression of being Rivas's tall, affable American sidekick.

In early December, within days of returning from Miami and the Cema episode, Chidester and Rivas went together to chat with Colonel Benavides in his office at the military school. Chidester says the meeting was uneventful; Benavides wasn't a suspect. But colleagues say that the colonel was so nervous he became physically ill. With another officer (since arrested for destroying evidence), Benavides was allegedly, during the days surrounding Chidester's visit, burping more than seventy logbooks that named the persons who came and went from the military school on the night of the murders.

Just after that meeting, Benavides apparently confessed privately to Rivas. How this confession came to light nearly a month later, via a U.S. military adviser named Major Eric Buckland, is a wonderfully complicated story. Yet nearly a year later it remains the only major break in the case.

Major Buckland was described by a congressional investigator who met him as "the genuine G.I. Joe." When I saw him during the November rebel offensive, he couldn't have seemed happier. "You know, our guys who were here ten years ago thought we were on the wrong side," he said. "That's not true anymore." The Jesuit killings a few days earlier had not changed his mind. In fact, he proposed to the high command that they launch a publicity campaign to blame the F.M.L.N. "If I found out that the military did this," he told another reporter, he'd transfer out.

But when he did find that out, Buckland didn't quit. He shut up. According to a signed statement, Buckland was told in late December by his Salvadoran counterpart, Colonel Carlos Aviles, that Benavides had gone to Rivas and said, in effect, "I did it. What can you do to help me?" Rivas apparently had become so frightened that he stopped investigating. He started seeking advice. He confided in his predecessor at the investigative unit, who in turn told Colonel Aviles. Now Aviles, an important nonTandona officer with a line to the Americans, was telling Buckland, in confidence.

Buckland said he kept quiet out of loyalty to Aviles. Two weeks passed before, distraught, he reported the story to his superior at the embassy. What happened next, in some respects, was even worse. Without informing Walker, who was in Washington, the head of the U.S. military group marched directly to see Colonel Ponce, bringing Buckland. When an enraged Ponce demanded to know the source implicating Benavides, the Americans told him. Colonel Aviles was summoned to sputter a denial, his career and possibly his life passing before his eyes. Said a senior U.S. official, "Unlike journalists, we don't protect our sources." Indeed, while the embassy has vowed publicly to protect any Salvadoran who steps forward with information about the case, the two Salvadorans to do so with important leads— one of them Mrs. Cema and the other Colonel Aviles—have found themselves, to their astonishment, burned by U.S. officials.

With Aviles exposed, Colonel Ponce was able to manage the episode, which had a rapid resolution. President Cristiani announced that the military was responsible for the killings. Confessions from soldiers were obtained, and Benavides and eight others (one soldier is a fugitive) were ordered arrested. The military, unhappy about handing over even one colonel—and a minor Tandona player at that—proclaimed the case closed. Ambassador Walker praised the arrests as "a historic step."

For Colonel Aviles the whole thing was a disaster. A short, garrulous officer who attended Jesuit prep school, he was placed under a version of house arrest. After the high command withdrew his assignment as military attache in Washington, he broke down and cried before a fellow officer. Now back in his old job above Ponce's office, he has the pained look of a man buying time.

Not surprisingly, Aviles still denies revealing anything to Buckland. But in his first comments to a journalist since the episode, he told me, ''The Jesuit case is a black hole that sucks in not only the entire armed forces but the entire country."

Amazingly, Rick Chidester discounts the entire Aviles-Buckland story. He believes that both men are lying. Why? Because he does not believe that Colonel Benavides ever confessed to Lieutenant Colonel Rivas. Why? Because Rivas denies ever having heard the confession— evidence that could convict Benavides. Rivas, says Chidester, ''is not a good liar." When I asked why Rivas, who refused to be interviewed, wouldn't tell me the same thing in person, Chidester explained, "He's gun-shy."

As the case dragged through the summer, speaking for Rivas led Chidester into what seems a serious impropriety. He informed the Jesuits that he had learned of a rumor that "the UCA" wanted to "disappear" the chief investigator—that is, kill him. To the Jesuits, who regarded Chidester's statement as an indirect threat, the nightmare seemed to be coming full circle.

Chidester has continued to deliver bad news. He says he warned the judge and attorneys in the case that U.S. intelligence had picked up on threats to kill them. Once a critic of the judge, who will eventually rule whether there is enough merit to bring Benavides and the others to trial, Chidester now appears to be in his confidence. When I went in July to see Benavides testify for the first time before the Fourth Criminal Court, the judge missed the start of proceedings. He emerged from his adjacent office after Chidester had exited quietly through a back door.

Like Walker, who sent a $1,000 donation to the UCA after the murders (it was returned), Chidester, a Catholic convert, is clearly troubled by the enmity of the Jesuits. He, too, says he is unhappy with the way the case is going. Colonel Benavides, who maintains his innocence, has the law on his side, since confessions by his co-defendants cannot be used as evidence against him. More important, Benavides is still backed by the military. Three more soldiers were arrested during the summer for lying to investigators. "There's a lot of perjury going on," Chidester says. "There are obvious interests in lying, and the only people who can change that are in the military."

In El Salvador, "if you have authority, you abuse it," says a U.S. officer. "There is a cloud of rumor and lies that covers everything."

Today, the Americans plainly want the case behind them. They want Colonel Benavides to become the first Salvadoran officer ever convicted of a human-rights violation. They want the Tandona weeded. They want this because they want the military to go on fighting with U.S. aid. "If this remains an open sore it will be dangerous, if not fatal, to our relationship here," says Walker. "There are some who believe the case shows the unredeemable evil of the armed forces, and I don't believe that."

But even among U.S. officials this is becoming a lonely position. At times, bitterness toward the military can boil over until it covers all El Salvador. "We're talking about thirty guys afraid to point the finger because the finger will point back at them," says a U.S. officer. "This is the way the country is. If you have authority, you abuse it. If you have access to funds, you steal them. If you're a boss, you screw your secretary. Deny everything. Reveal nothing. There is a cloud of rumor and lies that covers everything."

Outrage will now almost certainly cost the Salvadoran military money. This fall, the Senate is considering cutting military aid for next year by anywhere from 30 percent to the 50 percent proposed by Representative Moakley. Some legislators support the idea of resuming aid as a reward to the military if it cooperates with the investigation or the rebels launch another offensive.

What such formulas fail to address, of course, is whether the United States is doing anything to end the war, whether the military is, as Ambassador Walker insists, a good institution with some bad people, whether, finally, underwriting the Salvadoran military can be defended any longer as drawing the line against Communism. These issues are currently before Salvadorans in an unprecedented way. Terms like "impunity" and "demilitarization," even "Tandona"—rarely heard before outside the UCA campus—have passed into the public domain. They are debated on television talk shows.

Unfortunately, the individuals best prepared to channel such a debate toward peace are dead. This is a tragedy not only for Salvadorans—70,000 have died in the war—but also for those American policymakers searching for a graceful exit from El Salvador. The Jesuit priests left unfinished business. "They were killed because it was necessary to kill them," says a Jesuit colleague, Father Jon Sobrino, providing a truncated epitaph. "They fell in the battle because they were part of it."

The battle continues. The commando unit of the Atlacatl Battalion, as it turned out, survived the detention of its leaders. New commandos were sworn in by the military while I was in El Salvador. No mention of the Jesuits was made at the ceremony, which had its own religious fervor. The young soldiers vowed to kill "terrorists wherever we find them." They stood immobilized on the parade ground, their faces blackened with paint, framed by the battalion's motto: "For the Fatherland and with God."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now