Sign In to Your Account

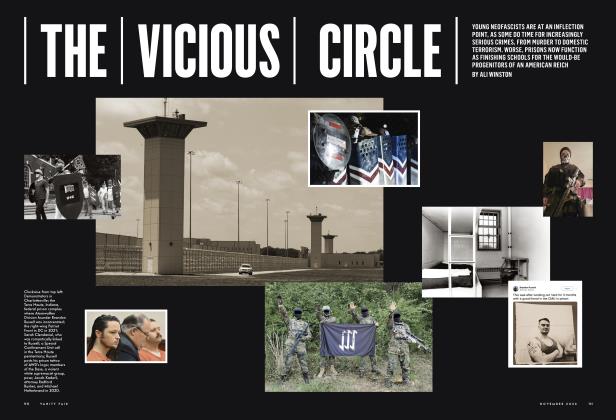

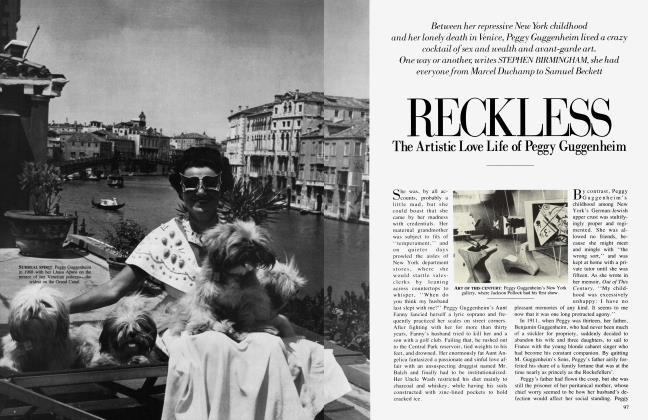

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Dreams of Ted Field

By all accounts, Ted Field should be satisfied. He's expecting a child with his third wife. He's built a $500 million fortune. He's been a major force in L.A.'s liberal and movie-industry elites, a death-defying racecar driver, and now he's launching his own record label. But the heir to the troubled Chicago retail dynasty is still searching. MICHAEL SHNAYERSON reports

He's the one with the woodsman's beard and the strange left hand. The one standing apart, with the blonde. The one who looks so out of place here, sidling past the odd lot of famous faces gathered under this big white party.tent on a Beverly Hills Sunday afternoon: Senators John Glenn and Howard Metzenbaum beside Ron and Nancy Reagan; Elton John and Ringo Starr brushing by Paula Abdul; Michael Eisner and Brandon Tartikoff asking autographs of Sandy Koufax and Joe Namath. He nods as he makes his way through this crazy quilt of American culture, past the carnival booths where children throw balls through hoops, at this weirdly overblown benefit picnic for the fight against pediatric AIDS on the back lawn of the most extravagant home in Los Angeles. He knows the guests know he's their host. And yet as he passes he can't help but notice that few make a point of saying hello. It's not that they don't like him. They just don't know him. They don't know what the hell to say.

Think of him as Jay Gatsby crossed with Jerry Garcia. Frederick Woodruff Field is young. He is rich. He is an emerging public figure who remains painfully shy. As if he is compensating for that shyness, everything you hear about him is big. Big house and parties. Big business. Big Hollywood splash. Even the aura of mystery that swirls around him, the legacy, and the rumors are big.

Ted Field is a man of several lives, every one of them chosen to escape the life that will always define him first: that of heir to Chicago's best-known family fortune. His older half-brother, Marshall Field V, bears the full family name, but the two inherited equal control of an empire built over four generations of hard work, misery, mental instability, and untimely death. It was Ted who chose to force the dissolution of that empire in 1983, resulting in the sale of its crown jewel, the Chicago Sun-Times, to Rupert Murdoch, and in an angry standoff between the two brothers, who haven't spoken since.

To Chicago's social elite, Ted remains the brat who took his money and ran back to a sybaritic California life of highspeed racecars and dabbling in films. In fact, Field's journey has been an earnest, even desperate search for self, an anguished effort to shake the mantle of heir from his shoulders and prove himself his own man.

By the cold gauge of money, Field has done better than well. Joining in hostile takeover runs with his mentor, Jimmy Goldsmith, investing in commodities and commercial real estate, he has more than doubled his postdissolution stake of $260 million, yielding him a prominent place on the Forbes Four Hundred list. Marshall, tending conservative investments and leading a proper Chicago life, has done well but not that well. Not nearly.

Eight years ago, Ted Field started Interscope Communications, which has since pushed twenty-two of its scripts through the studios onto the screen, extraordinary for an independent. Often drubbed by critics, Interscope films have shown a canny instinct for lowbrow, commercial comedy (Revenge of the Nerds, Three Men and a Baby, Cocktail). Now, with Disney and a Japanese-backed investment company called Nomura Babcock & Brown, Interscope has signed a deal that makes Field, overnight, one of Hollywood's biggest players, with over half a billion dollars for new films.

Field has lived well with the same relentless drive. His home is Green Acres, the old Harold Lloyd estate, restored to the grandeur that made it, on the eve of the Depression, Hollywood's most celebrated home. The big benefit parties—Democratic fund-raisers, social-issue events—that he and his wife, Susie, have thrown here have seemed geared to earn the ultimate grade of social acceptance. It was Field who last spring underwrote a save-the-rain-forest party that featured Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Paul Simon, and Don Henley and raised $1.1 million in a town where benefits raising one-quarter that amount have been cause for selfcongratulation.

When does a rich man know he's made it on his own? As Field keeps searching for an answer that doesn't exist, he rips through new businesses, new interests, and, say some, new friendships and romances with the same impatience and zeal. Houses, according to one embittered ex-chum, are his metaphor. Over the last eight years, Ted has bought, renovated, lived in, and sold a dozen multimillion-dollar residences. "Oh, he's definitely the biggest individual account in the world," enthuses Paris Moskopoulos, the Beverly Hills real-estate agent fortunate enough to have handled every one of these transactions. "He hasn't done it for money, either," Moskopoulos adds, though more often than not a profit has been made. Why then?

Moskopoulos pauses. "Restless," he suggests. "He's very restless."

If you spend any time with Ted Field, you'll hear him talk about lap times—the time it takes you to go around a track in a high-speed car. In an eightyear racing career, Field notched two recordbreaking lap times. It was the ultimate accolade for a restless soul. It was also a test of skill and judgment over money, a way, as Field puts it, of getting the monkey of inherited wealth off his back. "People would say, 'Oh, he's not a professional driver, he's just a rich kid.' I'd just say, 'Look at my lap times.' And that was enough."

The brothers haven't spoken since Ted forced the sale of the family Daner to Murdoch.

But the lap times are all the more remarkable because of the hand—the hand damaged in a race that defined Field's character in a greater, more awful way than Field ever intended.

''Everybody thinks the accident was what ended my racing career," Field says, settling into a big brown overstuffed chair in his huge dark-brown comer office on a high floor of Murdock Plaza, the Westwood office tower he bought from David Murdock some five years ago. ''Absolutely the opposite. It was in the second race I was ever in, at Riverside." As he talks, he gestures with the mangled left hand that is wrapped, as usual, in an Ace bandage, from which protrudes only an undamaged thumb.

"What happened was my car's engine died, and a tow truck came to help. The guy hooked up the towline to my roll bar and said, 'Here, hold this.' So I held it, with the line wrapped around my hand. He got into his truck and popped the clutch—exactly what he shouldn't have done. My formula racecar was yanked up and over, and was dragged fifty, maybe a hundred yards. My hand was trapped between the roll bar and the track. When I was pried apart from the car and taken to the hospital, I finally got over my shock enough to look at my hand. It looked like raw liver with pencils sticking out. The pencils were my finger bones."

Field unwraps the bandage to reveal a misshapen stump. Where his fingers once were, there are now only short flaps of flesh.

In the nightmare that followed, Field was told he'd likely never drive a passenger car again, let alone race. Within a week of the accident, he went out to the track and did a few laps to see if he could still do it. He could. So he resumed racing, despite the fact that for two years he continued to feel excruciating pain in his hand, the kind of pain, he says, that you feel when you hold your hand directly over a hot stove. He had to work the gearshift with his right hand, so that at speeds of up to 243 miles per hour he had only his left thumb with which to hold the wheel. Yet he went on to win several big races, including a three-man, twenty-four-hour endurance race at Daytona.

In Field's early Hollywood days, he took an interest in Jerzy Kosinski's novel Passion Play, and though the film was never made, the two men became friends; indeed, Kosinski may well be Field's best friend. Often, while Field was still racing, Kosinski would go out to watch. The sight of the man with one good hand racing fascinated the writer: "Next to the eyeball, the hand is the most sensitive part of the body," Kosinski declares, "and so the accident introduced Ted to a scope of pain that most of us never learn. It made him philosophical, though in fact he is perfectly balanced, I think, between philosophy and reality. I was dying each time we went to the races. I have pictures when his tire blew up at 164 miles per hour, and the car blew up, too. . . .But Ted just walked away from it. And he was as calm, at that moment, as at the start of the race."

To the press at least, Ted Field has been not only calm but mute—unwilling to grant an interview for the last fifteen of his thirty-eight years. Now he's at a turning point, turning straight up, and all the good news has gotten the better of him.

"Whatever else it becomes, Interscope as a film company has certainly accomplished what I initially set out to do," he says earnestly. "So it's time for me to start a new phase." Part of that new phase is Interscope Records. "I like the gut-feel businesses," he says. "You can't choose based on formula."

It's a bold bid to fill the void left by the sale of Geffen Records—the last independent of its era—for $550 million last spring to MCA. No fewer than eight start-ups are racing to fill that void, but all are spin-offs of major record companies. Field hopes his true independence—he'll own the company himself, as he does Interscope's film and finance arms—will let him move faster than the competition, just as David Geffen did. To run the company, he's hired his mirror opposite: Jimmy Iovine, a Brooklyn-born street kid who at twenty worked as a recording engineer for John Lennon and went on to produce, among others, Dire Straits, U2, and the Pretenders. Iovine says he marvels at Field's moral consistency. "I can always tell when someone starts moving on me—you know what I mean? And here's Ted, always saying, 'What's the right way to do this?' The guy is like a steamship." Geffen is also full of respect. "Ted has got big balls, and deep pockets, and he's going about it exactly the right way."

Field's other news is in the unlikely arena of worldchampionship chess. He himself is a serious player: he's beaten masters, he's drawn with grand masters. Reigning grand champion Garri Kasparov beat him easily enough last year on a visit to Green Acres, but calls Field one of the strongest amateurs he's ever seen. Still, Field says he knows he could never rank among the top players in the world. So he's found another way to win at the game: by taking it professional.

This fall, for the first time in the history of the sport, the opening games of the championship match between Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov have been promoted as an American-style high-stakes event at New York's Hotel Macklowe, with the concluding games held in Lyons, France. Field will be underwriting the New York games, having fun, and hoping to make a profit. His World Professional Chess Promotions Inc. will not, however, use his name on any program or board roster. "I don't want a title," he declares. "All that counts are lap times."

"Ted has got big balls, and deep pockets," says David Geffen.

It's a credo that some might also apply to Ted Field's personal life.

'Would you like some wine?" Susie Field, at twenty-eight, has straight blond hair, big blue eyes, and a perfect complexion, so perfect that you search the ovals of her face for blemishes, and marvel, when you fail to find even one, at the life that that suggests. Doubtless she looks even more radiant than usual, for Susie is pregnant, visibly so. This will be her third child in three years of marriage, and just to round out the threes, this is Ted's third marriage. Yet only a month earlier, Susie's hard-to-shock Hollywood girlfriends could be found trading stories of flagrant infidelities on Ted's part. Whether the rumors were true or spun out of whole cloth by observers jealous of Field's wealth and success, the marriage, declared Susie, was over.

It was decided at that time that Susie would move with their two young daughters into a $14 million house in the hills. After all, Ted's first wife, Judy, lives with her daughter by him in a Ted-bought, $3.5 million house in Bel-Air, while Ted's second wife, Barbara, lives with the daughter they adopted in a Ted-bought, $5 million house, also in BelAir. Though Ted and Susie have since worked out their differences, they decided to sell Green Acres anyway and move together into Susie's new house. Green Acres had come to seem too big, too much—a symbol for all that had troubled their marriage.

Two weeks after the big garden party, Susie Field appears in the high, wide doorway of Green Acres' library in a brilliant blue silk outfit that drapes around her growing belly like a magician's knotted scarves. It is early evening, and Ted is not yet home, or perhaps he is—it's hard to tell in a house of more than forty rooms.

Inside, Green Acres is not unlike San Simeon. Most of the Renaissance paintings are easy enough to identify: art books, open to the appropriate pages, lie carefully placed on wooden benches below each gilded frame. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese. "There's the Bellini,'' Susie says casually of a painting on the far wall of the large, sunken living room. "And there's the Renoir, over the fireplace.

"It's funny, we've never used this room," she adds, "except for entertaining."

It must be the kind of house, one imagines, where you would feel constrained from clumping around in a ratty old bathrobe.

"Yes," she agrees. "In fact, it takes so many in staff just to run the place that we really never have any privacy unless we're in our bedroom. And all the bodyguards—way too much security. That's why we're moving out."

Settling in the garden room, Susie describes the huge job she faced in restoring the house, back in 1986, after Ted landed it, along with five acres, for $6.5 million, in part because no one else wanted to pay the millions more needed to pull the estate out of disrepair. The kitchen hadn't been redone since the 1920s; the iceboxes and stoves were given to museums. Susie, who was also pregnant then, supervised the restoration herself.

It's a lovely story, but it lacks a telling detail: namely that Ted bought and moved into Green Acres with his second wife, Barbara. "Actually, Barbara fancied herself a decorator," one friend acknowledges. "That was her mistake. She emasculated the historical significance of the house; she had a gigantic serpentine couch, for example, put in the living room, the sort of thing that would have looked more appropriate in the lobby of a glitzy hotel. Susie came in and trashed all that Barbara had done, and spent far more money, but she did it right: she brought in experts and actually restored it."

Just how one wife succeeded another is one of the more delicate aspects of the Ted Field family saga. It was back in the early 1980s that Ted's first wife, Judy, faded from the scene. ''Judy was and is an enormously insecure lady," says a friend of that time. ''She was also sweet, pure, virginal, from an excellent family, and she was completely dismayed and amused by the life-style Ted adopted after he moved to L. A. "

Into her place came Barbara, a blonde from the Donna Rice school of social advancement whom Field had met at a Florida racetrack. ''It was Ted's way of thumbing his nose at everyone," one friend suggests, ''saying, 'You still have to be nice to her.' " Adds the friend, ''Barbara treated the help terribly, and she presided over Ted's friends like a queen. If you offended her, you'd be on her shitlist, and she'd try and get Ted not to like you." Barbara seems to have had a few cultural gaps as well. Told that one of her maids might have to leave the country for lack of a green card, she exclaimed, "So we'll get her a green card—we give enough money to Greenpeace, for God's sakes."

Though Susie stresses that Barbara lived with Ted as man and wife for only about six months, she was in his life for closer to three years, and managed to effect a couple of changes more lasting than her decorating job. One was a standard of spending. "Both Barbara and Susie spend money like water," says one friend. Barbara, for example, brought a whole carnival, complete with carnival-size stuffed animals as prizes, to their ranch in Santa Barbara to celebrate the birthday of Ted's daughter by Judy. (Susie went a bit further. Last winter, for her daughter Brittany's second birthday, she had actors in storybook costumes deliver silk-wrapped invitations replete with toys. Brittany's friends, and their parents, arrived at Green Acres to find each room of the house decorated to represent a different storybook scene, with more costumed actors—about sixty in all—to act out the parts.)

More important, Barbara talked Ted into adopting a child. The baby they chose was a girl, and hence not destined to be a sixth-generation heir; the ramifications, however, were still comforting. Eventually, according to Field, Barbara lost a heated legal battle to overturn their prenuptial agreement, but Ted chose to buy Joan Rivers's former house for the adopted daughter, a house, of course, in which Barbara would live, too.

Ted first met Susie soon after he moved to Southern California. Her father, Barry Bollman, helped design and build Ted's racecars. Susie lived just down the street, but Ted was married at the time. Besides, Susie was only seventeen years old. By the time Ted ran into her while she was buying a dog at a Beverly Center pet shop, seven years later, she had grown up, taken interior-design courses at a local college, and been linked with Rod Stewart.

"It was complicated when we met again," Susie relates. "Ted was married to Barbara and they'd applied to adopt. But we were engaged within a week." For a while, Ted and Susie were a covert couple. Then, finally, the adoption papers came through. "Actually, the papers came through about two weeks before he left," Susie explains. "But even those two weeks were so important in helping the baby get accustomed to him."

Ted and Susie have just learned that their third child— Ted's fifth—will, like the others, be a girl. Susie says she's decided to have two more children in quick succession, the hope being that both will be boys. Field shrugs off the importance of having a son, but Field watchers chuckle at that. "The game is: she who has the first son wins," declares a friend. "It's Henry VIII time."

Ted, it turns out, is home.-He wanders into the garden room, sits close to Susie, and as he chats, the two exchange little touches. Finally Susie begs off to get ready for a dinner party, and Ted continues the tour. "Just heard we may be getting an offer of forty-five," he says happily. Field has put Green Acres on the market for $55 million, the largest sum ever asked for an American residence.

Also on the market, for $29 million, is Field's ski chalet at the foot of Aspen Mountain. Perhaps as compensation, he recently scooped up, for $6 million, actor Michael Landon's newly renovated Malibu beach house, then had it gutted. Now it's all grays and blacks and whites inside, with as much marble as a mausoleum. Dominating the living room is an aquarium, in which swims a single creature: a restless, foot-long shark.

The Green Acres tour ends in a warren of basement rooms that are, in their own way, more intriguing than anything above. One is a cozy clubroom, (Continued from page 197)

(Continued on page 212)

with a fireplace from which Harold Lloyd, the story goes, would send up smoke signals so his pals would know to come visit. It takes a moment to realize that the tall boxes— perhaps forty in all—set side by side around three walls of the room are Susie's wardrobe, each box carefully marked by designer. "Well, part of the wardrobe, anyway," Field says with unmistakable pride.

Close by is the security room. A young security guard sits at a console of nineteen closed-circuit television-camera monitors capable of showing every square foot of the estate. Stuck into the waist of his pants, gangster-style, is a nine-millimeter pistol. On the wall beside the monitor screens is a black schematic diagram of the house and grounds. Four lighted lines of varying colors surround the house. The outermost line represents an electronicfence sensor. Next in are buried electrical cables that sense any movement across their force field. Then a network of infrared beams. Then another underground electrical cable. "We've had Secret Service guys tell us the security here is as good as the White House," declares Field. "I want anyone who's contemplating breaking and entering and endangering my family to know we have a little reception committee waiting for them."

Two more rooms. One is the workout room. Framed by mirrored walls, rows and rows of weight and aerobics machines silently await their single customer: Field works out alone. "Personal trainers—I don't believe in them," he scoffs. Next to that is a locked, wooden archway door. After a moment, one of the many servants materializes with a key, and the door, as in some C. S. Lewis novel, opens onto one of Ted Field's more private worlds.

A full set of drums, with gleaming cymbals, dominates the windowless chamber. Two electric guitars—one bass, one rhythm—stand nearby. As a teenager, Field played in garage bands. Now he jokes that he's the only one-handed drummer around; he holds his left stick in the crease between his thumb and the stump of his hand, the way he held racing-car steering wheels. On one wall hangs a huge framed Scavullo photograph of a woman with luminous blue eyes and teased-out blond hair. It takes a moment to recognize the woman as Susie.

What is it that suddenly seems so sad about this room?

The image of a rich boy, every wish fulfilled, playing with his toys alone.

There has clung to each generation of Fields an almost palpable sense of aloneness. Money does that, but in the Fields' case the burden of wealth has seemed only to augment a deeper alienation, one as ingrained in the family genes as quick-wittedness and pluck. More often than not, it has led to real despair.

The first Marshall Field was only twenty when he arrived in Chicago in 1856 with less than a dollar. A dour and driven man, he established the department stores that still bear his name, but derived little joy from his success. Nor did his family console him; for most of the thirty-three years they were married, his wife chose to live abroad. A year before his death, in 1906, his son Marshall Field Jr., at the age of thirty-seven, ended a purposeless, melancholic life by shooting himself in the abdomen.

Marshall Field III never did know for certain if his father had deliberately killed himself, but for the rest of his life he remembered, he said, the sound of the shot as he lay in his nursery. Brought up in Europe by a mother determined to keep her son a sane distance from the family ghosts, Marshall III led a frivolous life until his early forties, when the waste of it began to haunt him. In a move radical for the 1930s, he fought the family cafard by going to a psychoanalyst five times a week. After eighteen soul-searching months, he decided to throw himself into good causes, and from there found his way into newspaper publishing. A first effort, the liberal P.M. newspaper in New York, earned respect but little money, and folded in less than a decade. More successful was the Chicago Sun, which eventually became the Sun-Times.

Marshall III could not take the same pride in his personal life. The children of his first marriage, Marshall IV and Barbara, suffered lifelong psychic wounds from their father's abrupt departure into a second unhappy marriage, then a third. Both eventually were institutionalized, with Marshall IV characterized as being manicdepressive and subjected to regular doses of shock treatment, the panacea of the day. Yet Marshall IV was also perhaps the brightest of the Fields, having demonstrated a photographic memory at Harvard that initially brought accusations of cribbing on exams, but then won him a magna cum laude degree. He recovered well enough from his hospital ordeal to take charge of the Sun-Times, to bring it to profitability in the late 1950s, and even to buy Chicago's afternoon Daily News in 1959. But depression continued to dog him, and through three rocky marriages of his own he drank heavily and developed a dependence on prescription drugs. One earlyfall day in 1965, at the age of forty-nine, Marshall IV took an afternoon nap and failed to wake up. When a medical report revealed high levels of alcohol and drugs in his bloodstream, the suspicion was planted, and never disproved, that like his grandfather before him Marshall IV had taken his own life.

Both Ted and Marshall V have come to feel sure their father did not commit suicide. "My father just abused a number of things," Ted says. "Not only alcohol and drugs but food—he used to eat a stick of butter, just like that. So, needless to say, he had cholesterol problems." The abuses, Ted feels, trace not to some family curse but to his father's experiences as a navy gunner in World War II. "I remember him once showing me the shrapnel in his head, a golf-ball-size piece."

Ted was thirteen when his father died. By then he was living in Alaska with his mother, Marshall IV's second wife, Kay Woodruff, who had driven out there in a station wagon after the collapse of her marriage in 1963. "It did change my life," Field readily admits of the move. "We lived in Anchorage, in a middleclass development called College Village, and I went to public school rather than private school. My mother had decreed we'd live in an unshowy life-style and we certainly did. Probably I'm a Democrat because of the values she instilled in me. And maybe the Hollywood life is a glitzy reaction to enforced middle-class life." Field laughs. "But now I've come full circle, and, actually, I think my mother was right. But you know how it is: if your mother says don't do something, you want to rebel."

Kay's strong belief in Christian Science offered much to rebel against. Until the age of twenty-one, Ted was forced to go to twice-weekly church services and read a daily Bible lesson. "I'll tell you, Mary Baker Eddy had a great vocabulary, and I'm grateful to her for that, but I sure don't believe in a single one of her ideas," he says. "I think about as much of Christian Science as I do of the Hare Krishnas."

Kay's new life included a new career, as a reporter on the Anchorage Daily News, which she bought two years later, and a new husband, a newspaper editor named Larry Fanning. Not long after, tragically, Fanning died, leaving his stepson to cope with the loss of two father figures by the age of sixteen. "My stepfather was a really great guy whose influence—and Democratic values—remained with me," Field says.

Of little or no influence at the time was Ted's half-brother, Marshall V. Eleven years older, Marshall had grown up on the other side of the country and attended eastern prep schools. On the rare occasions when the two saw each other, Ted recalls, he admired Marshall, but he also admits his brother could be bullying: an indelible memory is of Marshall forcing him to watch as the older boy chopped the heads off snapping turtles.

Marshall was twenty-four when their father died. Within a year he went to Chicago to be groomed as the new head of Field Enterprises. Marshall was the perfect preppy—attractive, well tailored, conservative, with a self-deprecating wit—and while he had little more than a Harvard B.A. in fine arts to equip him, a regiment of advisers stood ready to help. By all accounts he was delighted to inherit the family empire, and concerned not so much with making his own mark as with simply "not blowing it." In these respects, he could not have been more different from Ted.

Brooding and self-conscious, Ted returned to Chicago at seventeen to enroll at Northwestern and felt the impact of his brother's position: to those who noticed him at all, he was the awkward, woolly kid brother, with none of Marshall's elan. He was lonely too. "One day I walked into my brother's office and asked the secretary if she knew anyone I could go out on a date with," he relates. "She had a friend with four daughters. I chose the one closest in age to me, we went out on a blind date, and I married her."

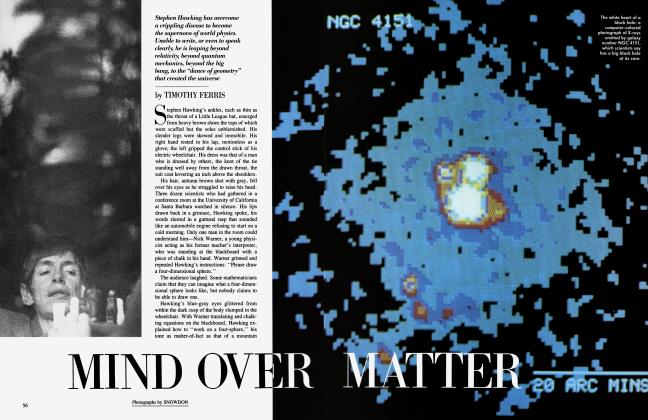

Ted dropped out of Northwestern and, not long after, out of Chicago. Over the next years, he would drift in and out of colleges, building up credits between bouts of racing, but never enough in any one institution to earn a degree. Now, ironically, he's become obsessive about learning. Inspired by Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time, he's plowed through serious physics texts, and plays a running game of history one-upmanship with lawyer Skip Brittenham. Ted even reads on the launch between his yachts and the Mediterranean shore—to get in a few more pages, one wonders, or to impress his guests?

Though Ted wasn't due to inherit his share of Field Enterprises until he turned twenty-five, he had little trouble persuading his trustees to dole out money for his increasingly expensive racecars. But he also took on the unusual burden of covering his mother's losses at the Anchorage Daily News—$5 million over seven years—until he decided he wouldn't have enough money to keep the paper going and pursue his own interests, and told his mother to sell or close down. To Ted's great relief, Kay Fanning was able at the last minute to sell to the McClatchy chain; she went on to become editor of The Christian Science Monitor.

It was on June 1, 1977, that Ted Field legally acquired 42.5 percent of his father's estate, worth about $100 million; his half-brother acquired the same share, the balance being divided between two Field sisters. Ted and Marshall signed a legal "agreement to agree," forbidding any deadlocks, and over the next seven years they made a number of shrewd investments, chief among them buying a handful of television stations. But profits failed to ease the tensions. "I'd go to these board meetings in Chicago," says Ted, "and all these conservative board members would look at me as if I was some kind of freak—because I was young, lived in California, liked to race cars, and wanted to enter the movie business. Not to mention the beard and the hand."

Ted's patience began to fray when he suggested strongly that Field Enterprises buy Southern California's Irvine real-estate company. "I knew it was worth more than the $300 to $400 million they were asking for it," Ted recalls, "but the board members just thought, How nice, he lives in Orange County and sees as far as the nearest company, which he thinks we ought to buy."

By 1983, Ted had tired of what he perceived as cavalier treatment. He forced the dissolution of the Field empire. "He was this enormously insecure, introverted kid, and he had an overwhelming desire to assert himself," says one close friend of the time."It was the economic and intellectual equivalent of that character in Taxi Driver. 'No one's paid any attention to me, so I'll put these guns up my sleeve and go use them—now you'll have to listen!' "

Marshall Field V, reached in Chicago, says his feelings today about that are as clear as they were then. "Ted forcing the family hand was perfectly fair," he says. "What I was angry about was forcing the sale of the paper. We'd both inherited it, and it seemed to me to force a sale to Rupert Murdoch because Murdoch was the highest bidder was just greedy—there was a very good group that bid $10 million less! But he didn't seem to want the Sun-Times in good hands. I suspect he was mad at the whole Field family."

Ted admits he's the one who forced the sale of the paper to Murdoch. "My mother was the top of a long list of enlightened people who said I shouldn't sell the SunTimes to Murdoch," he says. "To which I said I don't sell properties based on the politics of the buyer." Besides, he says, "I don't feel he's a bad guy. True, he's a conservative Republican and I'm a progressive Democrat. But Murdoch didn't destroy the paper." Moreover, he says, Marshall is wrong about the $10 million difference in bids. Though Murdoch was reported to be paying $90 million, Ted says that the final figure was about $103 million—and that the closest offer was about $60 million. With that kind of profit, Ted felt, "I could afford to do so much more politically and socially—it would dwarf any negative value of selling it to Murdoch. And it did."

Though the brothers haven't spoken since then, each seems to need to soften the fact. ''It's not as big a breakup as people make it out to be," says Marshall. "If we lived a block from each other we'd probably have seen each other."

"It is true that we don't talk to each other now," says Ted. "But we talk to mutual friends who pass on messages and good feelings between us. For example, Marshall heard I was interested in buying a certain painting, and he had information that it might be a forgery. He found a way to pass that on to me, and I was terribly grateful. By the same token, when he was recently negotiating to sell his Boston real-estate company, a number of possible buyers tried to get a negotiating edge by calling me and fishing for compromising information. I wouldn't even talk to them.

"All it will take is one call to break the ice," he adds, "and then we'll be back together again." But the call will have to come from Marshall. "I called him back in 1983, and Marshall brushed me off. Now it's his turn." Ted laughs. "I'll meet him halfway. Let's see—he lives in Chicago, I live in L.A. I'll meet him in Nebraska."

Marshall admits to spuming that call. "I was still plenty cheesed off," he says. "I said, 'Forget it.' "

So perhaps he'll return that call someday? Marshall pauses. "I don't know," he says.

Though Field hasn't raced for several years, social Chicagoans still tend to view him as a self-indulgent, even reckless sort. In fact, he is a virtual teetotaler who abhors drugs. And, as he points out, racecar drivers are anything but reckless.

"Two things that define me?" Field asks rhetorically. "Competitiveness—and control. I'm very competitive. I'm probably competitive to a fault. I play by the rules, but I do like to win. And I'm a control freak, which is one reason I loved racing so much. You have to concentrate utterly at every moment."

Like most self-analysis, Field's is a good start, but not necessarily the whole story. Robin "Lefty" Willner, a nationally ranked tennis pro in the over-sixty category, offers one take on Field's competitive streak. Nine years ago, Field began paying Willner to play with him almost every day. For five years, Field lost—every single set. Finally he began to win a set here, a set there, but still not two out of three. Now, perhaps once a year, Field wins his match.

As Field suggests, he can also go too far. At the family's weekend ranch in Santa Barbara, recalls a former woman friend, the worst moments were always on the doubles court. "You could never decide if it was better or worse to be on Ted's team. If you were on the other team, he'd be brutally competitive and resent it if you won. But if you were on his team and you fucked up, he'd scream at you, especially if you were a woman."

Control is harder to judge. Certainly Field, as sole owner of Interscope, exercises total control in theory, and with the Disney-Nomura deal he will have access to Hollywood's ultimate lever of control: the power to green-light a film. Yet how much does he really control Interscope films?

"Come on," scoffs one Disney executive. "Ted Field knows no more about day-to-day producing than you do. Bob Cort is the one who calls the shots."

"Actually, Cort, CAA, and Interscope's lawyer, Skip Brittenham, are the people in charge," says one ex-Interscope employee. "It's true that Ted has seen more movies than almost anyone—because he's had more time. But his role is just that of a dilettante."

Robert W. Cort, president of Interscope Communications, offers a smooth answer from the set of Three Men and a Little Lady—the sequel to Interscope's most commercial hit. "Ted and I have been remarkably in sync as partners," Cort avers. "We both love comedy, for example. Ted is this very dignified man, but he's got a kid inside him, and my favorite thing is to make Ted giggle." Still, it's Cort who brings the funny scripts in to share with Field—the ones he's already chosen to make. And it's Cort who carries them through.

"I think Bob Cort is the smartest executive in the movie industry," Field says, "except possibly Jeff Katzenberg. Why hire a guy like that and second-guess him? But do I let something as important as the film company be steered by other people? That's something you'll have to decide."

Socially, Field seems to control his life by surrounding himself with people who work for him. Virtually every summer, he takes fifteen or twenty guests on a Mediterranean cruise. Mike Marcus, a CAA agent who made important introductions for Field early on, is a close friend and frequent guest. So is lawyer Brittenham and realtor Moskopoulos. Each week, when Field engages in a fierce round of pickup basketball—he's been known to fly in from Aspen on a private plane just for the game—his fellow players are his lawyers, his computer consultants, his accountants.

As Interscope has blossomed, Field has, too. "Ted has gained a lot of selfconfidence in this period," suggests one ex-colleague. Yet, this observer feels, "he may also be less good at listening to criticism. In the early days he was real vulnerable, and he wanted to be told what was going on. Now he knows best, and people who say 'no' to him often get moved out of his life."

There may be no other American of his generation who has given or helped raise more money for social causes than Ted Field. Susie, too, has done much, serving on a long list of charity boards and helping, with Lyn Lear and Cindy Horn, to establish Hollywood's Environmental Media Association. But what sort of example do Ted and Susie Field set as environmentalists, in a home that must consume as much energy as some Third World countries, and with so many cars, and a private plane, and Susie taking 180 pieces of luggage on her last European trip?

"Yes, it's hypocritical," Ted says. "In fact, it's even more hypocritical that I own industrial parks. If you're worried about the number of light bulbs in my house, worry about the potential pollution of those parks! But my companies do comply with the law, and I don't make the laws. Nor do I profess to be an environmentalist. Susie and I do separate our cans and bottles and papers at the house. But am I going to start riding a bicycle to work? No—that's for some actor to do. I want to give money to help, and maybe that's what I can do best."

Ted has also been a major fund-raiser for the Democratic Party, even though the candidates he supports would probably view his hostile takeover runs as greenmail. "The Democrats confuse overleveraging with hostile takeovers, and assume they're all bad," Field declares. "Ironically, they let themselves be hoodwinked by what I call an unholy alliance of Republican government and Republican corporate America."

Marshall suggests a deeper contradiction about Ted's new visibility. "Personally he's a terribly private person," he says. "And what's interesting is why he chooses to have such a public life-style."

Admittedly, Ted's public side is hardly more than the occasional days the gates at Green Acres have slid open for a benefit party. Still, such grand-scale fund-raising was bound to have a cost. "It doesn't take a genius to figure out that when you have the best garage band in the world play at your party, people are going to say you were just doing it for the glamour," says Ted. "But what were we to do? When you go back to the charity, they say publicity is what they want. So you give it to them, and then the press accuses you of seeking it for yourself."

With the sale of Green Acres, Field says, his benefit-party days will end. And so may the brief reign of the public Ted Field. "One reason to have Green Acres was that it was perfect for fund-raisers. And the money raised was like lap times. But I had Susie doing it on such a large scale, and was so interested in how much money we could raise, I just got too competitive about that too. And that put us under great pressure.

"That house was like a character in our lives," Field adds, "and it's now just being written out of the script."

In a script, the writer could call for the camera to pull back from happy-again Field and pregnant wife: sunset over house with "For Sale" sign in front, music up, credits roll. In real life the search goes on, and the answer bobs just out of reach. "It's everybody's greatest concern about Ted that lasting happiness eludes him," says one friend. "What do you do when everything comes easily to you? When you've never known what it is to achieve something solely through your own efforts?"

There are those who also wonder if Field's fervor is a sign of the family curse. Marshall, for one, was quoted at the time of the dissolution as saying "Ted has the same problem his father had, and I consider that serious." Today he admits having spoken in the heat of the moment. But he's also not sure he was wrong. "I don't really know if he has it or not, " he says. "I do know that my father's manic-depressiveness didn't hit him until his forties."

After four generations, that is a specter that cannot be dismissed. And yet Ted Field, less than two years from forty, is healthier at his age than any of his forebears. He is also more accomplished than any since the first Marshall Field. Excitedly he speaks of expanding from television, movies, and records into publishing, of creating, as he puts it, a small-scale, private Time Warner. If he manages that, he may yet be the rebel who smashed a fading family empire, only to start a new Field dynasty.

He still won't have made it on his own. But then, he may not really mind.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now