Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

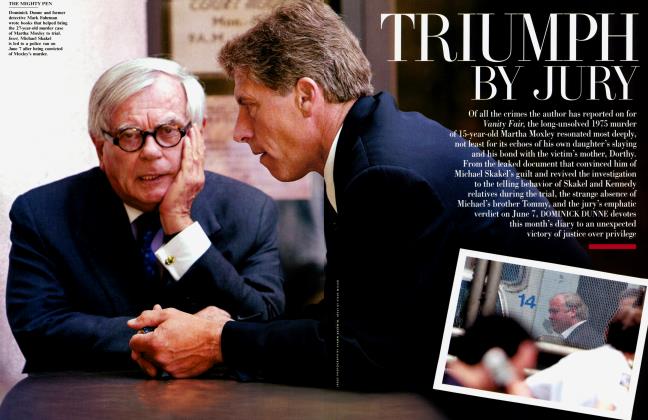

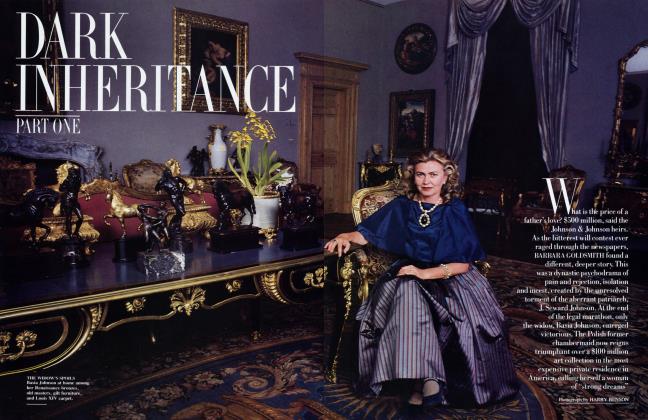

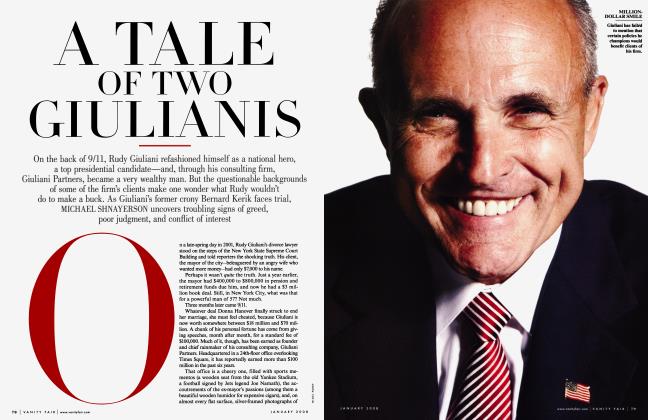

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe cold war between Tita, fifth wife of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, and his children by previous marriages, for control of the $2.7 billion family trust, erupted in 1999 into one of the most expensive private lawsuits in history. Finally settled in February, just before the baron's death, the conflict mirrored an epic emotional drama that drove his voracious acquisition of one of the world's great art collections. Interviewing the combatants, MICHAEL SHNAYERSON wonders if the truce—and the treasure trove that fills both the Villa Favorita and Madrid's Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza— can survive that poisoned legacy

August 2002 Michael Shnayerson Helmut NewtonThe cold war between Tita, fifth wife of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, and his children by previous marriages, for control of the $2.7 billion family trust, erupted in 1999 into one of the most expensive private lawsuits in history. Finally settled in February, just before the baron's death, the conflict mirrored an epic emotional drama that drove his voracious acquisition of one of the world's great art collections. Interviewing the combatants, MICHAEL SHNAYERSON wonders if the truce—and the treasure trove that fills both the Villa Favorita and Madrid's Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza— can survive that poisoned legacy

August 2002 Michael Shnayerson Helmut Newton“A Hungarian Gypsy once read his hands and said, You re going to die poor and completely alone. ’ That prediction gnawed at him over the years."

On a fragrant May evening in Madrid, paparazzi crowd the steps of Los Jeronimos church beside the Prado. Inside, the pews are nearly full. Suddenly an entrance makes all heads turn. Flashbulbs popping in her wake, a blonde woman in black advances down the aisle, unbejeweled but for a necklace of gray pearls the size of shooter marbles. Half a step behind her looms a tall young man, slope-shouldered, his own blond hair framing a handsome if somewhat vacant face. If he were American, he’d make a perfect Biff. Instead, his name is Borja.

The man whose memorial Mass this is gave the boy, now age 22, his surname—adopted him, and took Borja’s mother as his fifth and final wife. So the former Carmen Cervera of Barcelona, better known as Tita, onetime scrappy social outcast and 1962’s Miss Spain, is the baroness and now widow of one of Europe’s wealthiest industrialists, who amassed one of the world’s great collections of art. A sea of dignitaries gathers around the baroness and her son up by the altar, but their condolences, muddied by the church’s acoustics, sound like congratulations, and the whole scene, curiously, looks less like a funeral than like a triumphal march. So in a sense it is: at the end of one of Europe’s messiest marathons of marriage and divorce, Tita and Borja are the ones at the finish line.

The saga of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bomemisza, dead in April at 81, is first a story of art, much of it first-rate art, bought up over decades with a passion bordering on the pathological. Heini, as he was known, liked to say that if he didn’t buy a picture a week he felt unhappy. The paintings, from old masters to modem, would come to fill the walls of the Villa Favorita, his family home on Lake Lugano, Switzerland, as well as those of his other homes, in London and Gloucestershire, England, Paris, Monaco, Jamaica, and, eventually, Spain. He sent batches of paintings on tour in the U.S., which is how many Americans came to know his name, and he arranged important cultural exchanges between the West and the pre-glasnost Soviet Union. Then, in a spectacle that mesmerized the art world, he had European governments compete against one another to acquire the bulk of his collection. Spain won the contest, helped in no small part by Tita, and so some 800 paintings now fill the Museo Thyssen-Bomemisza, catty-corner to the Prado, boosting Madrid into the pantheon of art-world capitals.

But the baron’s life is also a story of recurrent personal sorrow, of a lonely heir growing up amid the ruins of a bitter marriage and resolving to lead a happier life, but failing time and again to secure it. Of a grown son seeing his late father’s old-master collection dispersed among squabbling relatives, and as a result working for years to buy the paintings back, only to have his own, much larger collection contested by his children. Of an older man struggling to be the paterfamilias that his father never was, yet ending up suing his firstborn son in a bizarre trial that became one of the most expensive private cases in legal history.

In the baron’s last months, the simple desire for peace in his family overrode all else. But in the aftermath of his death, a number of legal and emotional complexities remain, like sparking wires, to threaten a fragile accord. One cause of those sparks is Tita.

“We never said anything to each other that wasn’t true,” Tita says, chain-smoking in the living room of her sprawling pagoda-roofed house on the outskirts of Madrid. She’s explaining why her marriage worked so well. “Heini was not a person who would ever say one thing when he meant another. And me too: I was as open with him as he was with me.” That, she feels, is why she was able to make Baron Thyssen-Bomemisza happy in a way that none of his previous four wives had. In an interview published after his death in the worshipful Spanish magazine jHola!, the baron appeared to confirm this. “Today I’m a happy man,” he declared, “and my happiness is all due to my wife Carmen, who loves me, and whom I love.” By then, however, the baron was on heavy medication and much enfeebled, by some reports virtually unable to speak for himself.

At 59 the baroness remains a very attractive woman, lithe and sun-bronzed, spunky and engaging and blunt. Her house in Madrid is incongruously grand, its central hall dominated by huge Venetian chandeliers and brass columns. The living room she’s in has an extraordinary Tiffany lamp in one comer, an 18th-century Chinese triptych glassed over as a coffee table, paintings by Childe Hassam and other Impressionists on the walls, and a view of the Olympic-size pool, beyond which gardens cascade into undulating waves of sculpted, golf-course-like lawn.

“I’ve never met a man who in such difficult circumstances with his wives behaved so well."

Tita says she played no part in her husband’s decision to sue his son Georg-Heinrich, nor in the decision to drop the suit in February. “u couldn’t influence him to do anything other than what he wanted to do,” she says. “I always tried to do what he wanted. If he said, ‘Let’s go and throw both of us in the middle of the lake,’ I would do it.”

Those do sound like words that would please the baron, who once famously declared that he loved paintings and women, but preferred paintings because “you hang them on a wall and they stay silent.” But they’re strikingly at odds with the view of some of his children, who feel that Tita, from the start, manipulated her husband, ultimately pulling the strings of a stroke-diminished man in a brazen attempt to break the trust that contained his billion-dollar business empire in order to put the businesses into a trust she controlled. “What she attempted,” says one of the children’s lawyers, “is the greatest robbery in history.” Tita strongly denies this. “No way was the man manipulated,” she says. “He wanted to get back what he was due.”

“If he said.' ‘Let’s go and throw both of us in the middle of the lake, ’’’says the baroness; “I would do it. ”

His children agree that in business, for most of his life, the baron made his own decisions. But even as a young man, they say, he seemed maddeningly at the mercy of the women in his life. It was a mystery, this deep emotional vulnerability, but clearly it owed much to the forces that had shaped his destiny, well before he was bom.

he fortune came from chicken wire. Heini’s grandfather August Thyssen was a German peasant who saw what his neighbors needed, and parlayed his profits into a steel-and-armaments empire that helped support Bismarck’s military might. August liked art enough to commission a set of six marble sculptures from Rodin, but it was his two sons, Fritz and Heinrich, who started collecting in earnest.

Fritz sympathized with Hitler and helped empower the Nazis with the steel mills he inherited upon his father’s death in 1926; he bought some of his art from fleeing German Jews in the 1930s. Fritz broke with the Nazis and was sent by them to a concentration camp, but at the war’s end the Allies thought little better of him, and jailed him for several more years. He died among bitter German exiles in Argentina in 1951.

The other son, Heinrich senior, a cold and formal man, at least abhorred his brother’s politics. He had already washed his hands of Germany in 1905, starting a new life in Hungary and marrying the daughter of the king’s chamberlain. Because the chamberlain had no sons, he adopted his son-in-law and bequeathed him his title—a barony—as well as his surname, Bomemisza. Strictly speaking, this was a bogus move. “You can’t do that,” sniffs journalist and bloodline royal Taki Theodoracopulos. “u can’t even do that in a Prisoner of Zenda-type country like Hungary. They’re not in the Almanach de Gotha. It doesn’t lie; the real families are in there. You’re either born into it or not. The Thyssens were not in.”

The new baron’s match turned out to be a loveless one and would have dissolved years sooner than it did had August not insisted on Heinrich’s having a suitable male heir. A first son, Stefan, proved sickly and unfit for business. A second son—Hans Heinrich—was duly produced in 1921, in Scheveningen, the Netherlands. The boy was left in the care of a nanny while the mother led a decadent social life and the baron amused himself by acquiring old-master paintings—more than 500 in all. Many he bought from American robber barons broken by the Crash of 1929. The divorce came soon after. The boy’s mother apparently had no interest in bringing her son to live with her. Instead, Heini went to live in Switzerland, where he remained in the care of his nanny, the one figure who showed him love. Family lore has it that upon Heini’s 18th birthday his father fired the nanny and forbade her to see her charge again. Bereft, she reportedly committed suicide soon after.

Heini was only 26 when his father died in 1947, leaving him the bulk of his estate and control of his German-based business interests, mostly in shipping. They had been ravaged by the war, and Heini would spend the next years struggling to build them back up. But he would do so methodically, expanding all the while into plastics, glass, container leasing, and electric-power stations. At the time of Heini’s death this year, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Group was a global conglomerate involved in more than 100 businesses, the whole works valued at as much as $2.7 billion.

s sole executor of his father’s will, Heini planned to keep intact Heinrich senior’s old-master collection, housed in a gallery on the grounds of the Villa Favorita. This was not received well by his siblings, particularly his two sisters and their husbands. Lawsuits followed, and Heini was forced to break up the collection. He made it his mission to buy back as many of those paintings as he could— one sister actually sold all her paintings back to him; the other refused, so Heini had to buy them off the market as they appeared—and began, cautiously at first, adding other old masters. Collecting for Heini, one dealer would later suggest, was about more than the art itself. It was a way of trying to please the cold, distant figure who had been his father.

Just before his father’s death, Heini had married a true royal: German Princess Teresa of Lippe. The match was a disaster. “She was from a grand family, and treated him as if it were a terrible misalliance,” recalls one friend. (Inheriting his father’s dubious title of baron apparently did little to elevate Heini in the princess’s eyes.) Teresa bore him his first son, Georg-Heinrich, but Heini suspected the child wasn’t his own. In the thick of the later lawsuit between father and son, Tita would tell two reporters from The Wall Street Journal that Georg-Heinrich’s genetic father was Ivan Batthyany, late husband of one of Heini’s sisters, and point out physical similarities in pictures of the two. Princess Teresa adamantly denied the charge, telling one reporter, “My son will submit immediately to a DNA test providing that my ex-husband does the same.”

Divorced at great cost from the princess, Heini plunged without hesitation into marriage again, this time to an extraordinary British model, Nina Dyer—a mistake that made his first marriage seem prudent.

Dyer frequented Paris’s most fashionable nightclubs—the Elephant Blanc, Jimmy’s Bar, Moulin Rouge—with a cafe-society set that included the model Bettina, Porfirio Rubirosa, and Aly Khan. Also a tall, handsome, European actor named Christian Marquand, who was Nina Dyer’s lover.

Like a lot of her model friends, Dyer was on the prowl for a very rich husband, and Thyssen fit the bill nicely. “She was mysterious and unavailable, which made Thyssen crazy about her,” recalls designer China Machado. The black panther that Dyer kept in her apartment astonished the young industrialist as well. According to one friend, Dyer continued her affair with Marquand after marrying Thyssen in 1954, and went as far as to buy her lover an Aston Martin and a private plane with her new husband’s money. The marriage lasted only a year, and after the divorce, Dyer embarked on an affair with a woman, and later married Prince Sadruddin Khan, brother of Aly Khan. But a second rich man made her no happier than the first: in 1965, Dyer died of a drug overdose that is widely assumed to have been suicide.

Unrepentant—a man, as one friend put it, who made the mistake of marrying all his lovers—Heini took a third wife in 1956. To longtime Thyssen-watchers, Scottish model Fiona Campbell-Walter remains the most beautiful of the lot, fine-boned, with flaming red hair. With her, Heini soon had a second child, Francesca—his only daughter and, some would say, the only child indubitably his own. Yet his marital troubles would soon begin again.

When I was very young, before my parents got divorced, we’d sometimes go off, just the two of us, and have great fun,” recalls Archduchess Francesca von Habsburg of her father. “He had a convertible Mercedes at one point. He’d put me in the back and drive around like the blazes. Of course, I wasn’t strapped in—there were no safety belts in those days. He’d do tailspins in the snow, whipping around in circles. I’d be thrilled out of my mind; my mother would understandably be apoplectic about his irresponsible behavior, but he was all about living life to the fullest, regardless of the consequences!”

Francesca, tall and stately at 44, sips her cappuccino at a sidewalk cafe on the main street of old Dubrovnik, the Croatian medieval fortress town on the Adriatic Sea. She and her three young, towheaded children, with the children’s nanny, are here while her husband, Karl von Habsburg, attends East Timor’s independence ceremony as head of a political advocacy organization. She has come partly to start fixing up her and her husband’s newly purchased home within the fortress walls, partly to oversee the latest restoration work being done by the ARCH Foundation, which she founded. Its current projects include everything from Renaissance church panels to a Franciscan monastery on the nearby island of Lopud. Her father’s death still brings tears to her eyes, and a jumble of feelings: deep love, regret, and a pang or two of lingering frustration.

By the time Francesca was riding in her father’s Mercedes, her parents’ marriage had crumbled. Like one if not both of his first two wives, Campbell-Walter had taken a lover: Sheldon Reynolds, a witty and attractive American television producer (.Foreign Intrigue). Once again, Heini had been cuckolded. Once again, he endured the indiscretions—longer, at least, than many others might have done—even when his wife bore a child, Lome, who was, several observers believe, Reynolds’s son.

“I’ve never met a man who in such difficult circumstances with his wives behaved so well,” says one woman close to the situation. “With all the women in his life, Heini was a prince of a man.” Though he suspected that the boy was Reynolds’s, he took him as his own, bestowing upon him the family name and all rights of inheritance.

The real loser, in a sense, was Reynolds, who backed off, watching his purported son grow up from afar. Eventually he married Andrea Frottier-Duche, who, after divorcing Reynolds, would make her mark on society as Claus von Billow’s inamorata of the 1980s. At some point, Heini, ever the gentleman, arranged through Andrea to have Reynolds meet Lome as an adult, though the boy remained a Thyssen-Bornemisza. Living now in upstate New York, Sheldon Reynolds listens in silence to a suggestion that he set the record straight. “I knew Heini,” he says distantly, “and that’s it.”

Heini’s marriage to Fiona lasted into the mid-1960s, partly because he still adored her, partly because he had a horror, feels his daughter, of being abandoned. “A Hungarian Gypsy once read his hands when he was quite young, and said, ‘You’re going to die poor, and completely alone.’ That prediction gnawed at him over the years. The fear of being alone was something that he’d suffered from in his childhood, so it remained with him.”

Francesca was six years old when her parents separated. Neither parent bothered to tell her the news. “My life just changed overnight, and no one felt it reasonable to explain why and what it would mean to me at the time,” she says sadly. Fiona settled in England with Lome, five years Francesca’s junior, while Francesca was put in boarding school in Switzerland. There she remained for the rest of her childhood. “I was very jealous of Lome, that he could move to London with Ma and I had to continue living in Switzerland alone at boarding school,” Francesca recalls. “Now, having patched up my relationship with my mother, I understand that I was a very angry little girl. And that made it very difficult for her to have me in London. When you feel you’ve been abandoned by your parents, you get so angry you become impossible to live with.”

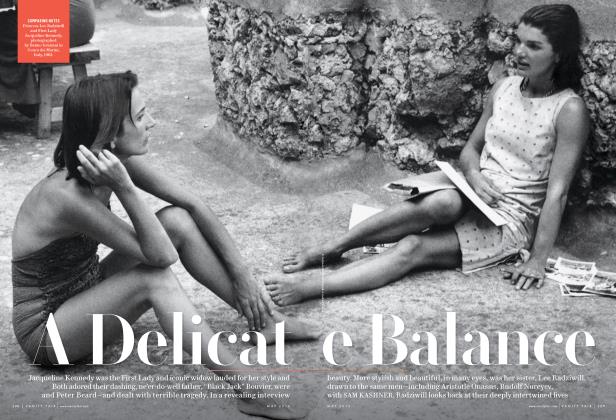

After her divorce, Fiona embarked on a romance with Alexander Onassis, despite the disapproval of his father, Aristotle, who had just earned widespread disapproval himself for marrying Jacqueline Kennedy. Tragically, Alexander died in a plane crash in 1973. Today, after some reportedly turbulent years, Fiona is a doting grandmother, leading a healthy, quiet life.

Heini was on the prowl again, in a none too subtle way. One very elegant New York woman recalls being set up with him at this time through mutual friends. “He was very urbane, trying to impress me with the details of his incredible life,” she recalls. “But I also thought he was cold. I like men who are funny; that was not the impression I had.” After two dinners, the woman got a call from the mutual friends: would she like to go to Europe on the baron’s private plane for a third date? The woman declined. Another New York woman introduced to him at that time was underwhelmed, too. “Very sallow skin and bad, spaced teeth. And a funny voice,” she recalls. “He was kind of silly, but there was also a presumption in his silliness that everyone should pay attention to him.”

Denise Shorto, a young, Brazilian-born beauty of English and Scottish expatriate parents, thought rather better of Heini when she met him in Gstaad. Her father was the Coca-Cola bottler for northeastern Brazil. He sent his four daughters and two sons to school in Switzerland, and there Denise remained, flirting through the winter season at Gstaad with various prospects. One friend recalls her renting a chalet with two of her sisters. “They didn’t have as much money as they were thought to have,” recalls the friend. “They had three good dresses, and they’d share them. Whoever had a date got to wear the Pucci.”

Heini was getting older, but his wives were getting younger: Denise was some 20 years his junior. His 1967 marriage to Denise was a happy one at first—happy, indeed, for several years. Along with her beauty—petite, with long blond hair and a beautiful complexion—Denise possessed a quicksilver mind and exuberant, almost manic energy. According to one of her brothers, Roberto, she gave Heini the confidence to fire some of the more ossified members of his executive board and take new chances in business. She orchestrated a “face-lift” of the Villa Favorita and let in the fresh air of new friends and art-world colleagues. After dinner she and Heini would lead the way from the main house across the lawn. “We had this key that would open the gallery,” she explains in Madrid. “We’d unlock the door and walk among the paintings. It was a private museum.”

As often as not, the houseguests would include one or more of Denise’s siblings. When Francesca went to the Villa Favorita to visit her father, she felt that a whole new family had moved in. And the father who had once been so warm was bafflingly distant. If Francesca tried to engage him, the sense she got was that children should be seen and not heard.

At Denise’s urging, Heini ventured from the staid world of old masters and began buying newer works his father would have abhorred. “As a collector, he had stopped at German Expressionists when I met him,” Denise says. “We built up the whole modern collection together—there’s a story behind every painting.”

With Denise beside him, the baron was collecting with a new ferocity. “He might go to an auction, fail to get one painting, and so buy another he hadn’t intended to buy, just because he’d wanted to buy a painting,” recalls Simon de Pury, his curator at the time (now chairman of the auction house Phillips de Pury & Luxembourg). And not just paintings. “Heini was buying right across the board: gold boxes, silver, Renaissance bronze, carpets ...”

Modern American art, though, was his main focus now. “European collectors and museums at that time were buying only post-World War II American art,” explains de Pury. “He was the first European to show a great interest in 19th-century American artists like Thomas Moran, Frederick Church, and Winslow Homer. Also early-20th-century painters like Edward Hopper.” So voracious was his appetite that dealers knew to show every newly available major painting to Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza first—chances were he’d buy it. But a select few dealers had the inside track.

One was Denise’s brother Roberto, just 18 when his sister married Heini. Soon enough, Roberto was leading Heini to paintings by the English contemporary stars Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

Yet Heini was not always comfortable with modern artists’ innovations. One memorable weekend, Roberto had Andy Warhol visit the Villa Favorita in order to begin a portrait of Denise. By Saturday, Heini was pulling Roberto aside. “When’s he going to start the preliminary drawings?” the baron hissed. Literally as Warhol was saying his good-byes to a fuming baron, he blithely took a couple of snapshots of Denise against a wall. “That’s what he works from?” the baron raged after Warhol swanned out. When the typical Warhol silkscreen of Denise arrived, Heini sent it back.

Soon another dealer was crowding Roberto’s turf. Tall, blond, and rakishly handsome, Franco Rappetti was a “beautiful hustler,” as one friend put it, from Genoa, Italy. Despite his modest background, Rappetti charmed his way into the baron’s circle—and into Denise’s bed. “Finally the penny dropped,” as Taki puts it. The baron realized he’d been cuckolded yet again. And, according to some observers of the period, he seemed, once again, unwilling or unable to take action.

The three of them actually hung out together. Rappetti and Heini would play backgammon for hours at the Villa Favorita. On Sardinia, they’d go out with Denise in Rappetti’s Don Aronow-designed Magnum speedboat, The Rapage. (“Like ‘rampage,’ ” one observer explains. Rappetti had a black Magnum; Denise had a blue one.) Then the three became four as Denise presented the baron with another son, Alexander. Once again the issue of paternity was murky: some would say that Alexander looked a lot like Franco Rappetti and not at all like Heini Thyssen-Bornemisza. Once again the baron took the boy as his own. Once again matters went from bad to worse.

Rappetti, who was a heavy drinker, graduated to cocaine. Meanwhile, a third dealer had elbowed his way into the baron’s affections: the notorious Andrew Crispo. Heini had stopped in at the up-and-comer’s 57th Street gallery in Manhattan and noted that a Charles Demuth watercolor on loan for Crispo’s first big show had a placard with the name of the owner misspelled. “How do you know?” Crispo demanded. “Because I am he,” the baron replied.

Crispo jumped at the prospect of being the baron’s new U.S. dealer for modem art. But there was the matter of Rappetti in Europe. Crispo later recounted to journalist Anthony Haden-Guest that Rappetti had come to him to demand a commission for any painting Crispo sold to the baron, and that Crispo refused. For a year, Crispo said, he was frozen out. But then, on June 8,1978, his fortunes improved. On that day, in Manhattan, Rappetti somehow flew out a window of the Meurice hotel on West 58th Street.

The baron’s first words, upon arriving in New York the day after Rappetti’s death, were reportedly “Does Denise blame me?” One good friend of Rappetti’s says the truth was more mundane: Rappetti’s cocaine habit had spun out of control. He had mounting debts and a deepening sense of paranoia. He kept saying to one of the last people who saw him alive, “They’re after me. They want me dead.” But at the end, the friend says, he was merely a man alone who jumped.

Still, Heini was undeniably delighted by the news. “He was grinning from ear to ear when he walked into the Waldorf,” recalls Nona Gordon Summers, a friend of Denise’s who helped comfort her in the aftermath. “I’ve never seen someone so happy as [Heini was] when Rappetti died.” Heini had come over to help arrange the quick transportation of Rappetti’s body to Europe—without autopsy, it would often be noted, though this was almost certainly an act of extraordinary chivalry, not a cover-up. Crispo helped the baron make the arrangements. When he learned that the cost of flying Rappetti back in a special casket on a chartered plane would be $150,000, he gasped. “Isn’t that a bit expensive?” he asked.

“Believe me,” the baron said, “it’s a bargain.”

Now Crispo became Heini’s principal art dealer, forcing all others to go through him or be frozen out. “The word was ‘If you want to sell to Heini, you have to go through Andrew Crispo,’” recalls a former New York art dealer. “So one never did get anything to Heini.” The dealers’ revenge, adds the dealer, is that, “in terms of art, when [Heini] started buying American art through Crispo, he bought badly.”

Denise, by one dealer’s account, allowed Crispo to replace Rappetti as her husband’s principal dealer. Later, Crispo would say that his sales to Heini climbed to as much as $3 million in a single month. But like Rappetti he spent an increasing share of his commissions on cocaine, which led, for him, to increasingly dangerous games of S&M sex, in a gallery office stocked with leather masks, handcuffs, and the like. He would soon be implicated in the hideous 1985 S&M murder of a Norwegian male fashion student and be jailed, eventually, for tax evasion. The baron would come to see that Crispo, however fawning and amusing he was, could not be trusted. But probably the real cause of Heini’s break with Crispo was that Denise had lost her influence.

The two stayed married for years after Rappetti’s death, but these were the baron’s darkest days, made worse by prodigious drinking. “Frankly, alcohol was a problem for him,” says one observer of the period. “While he was in his 40s he carried it off, but it became more acute and nasty. There would be whiskeys and Bloody Marys in the morning, followed by wine at lunch. Then he gave up spirits and drank only wine, but it was the negotiating that a heavy drinker does with his habit.”

The drinking led, in turn, to fights. A houseguest of the time recalls, “I was always going to bed and hearing the doors slamming_ Neither had done any therapeutic work, so the heavy baggage would come out every time they fought.” Later, the baron would say that he lacked the stomach to seek another divorce. Instead, he morosely wished that his private plane might crash with him inside it.

Then came the day, he would say, that changed his life: the day that he met Tita.

Heini was in Sardinia in 1981, dividing his time between a villa and his 50foot yacht, Hanse, when his old friend Fred Horowitz, a Swiss jeweler and man-abouttown, invited him and Denise to dinner. Tita was Horowitz’s houseguest; she had been scheduled to leave that morning but, she recalls, the planes were full, so she stayed. Horowitz and his girlfriend had also suggested that Heini might be worth sticking around to meet.

Tita recalls Heini fixing her with an intense, smoldering look. Another participant at the dinner recalls Tita as being unsubtle at best: “half naked.” Heini had the Horowitz household over for lunch the next day. “Watch out,” Roberto Shorto cautioned his sister Denise. But it was too late. That evening, Heini invited Tita out to his yacht and kissed her, as she recounts, on the open deck. “Everyone in Sardinia,” she says, “started talking.”

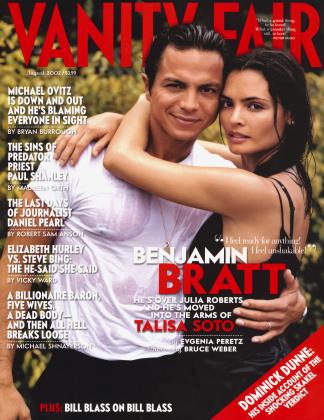

Gorgeous and vibrant, if unsophisticated, Tita had more than her share of colorful stories for a woman of 38. In 1963, after winning the title of Miss Spain, she had met actor Lex Barker of Tarzan fame on a plane and become, as she would with Heini, his fifth and final wife. (Barker’s earlier wives had included actresses Lana Turner and Arlene Dahl.) Barker was in his mid-40s, well past his Tarzan days, but had revived his career in Europe, starring in German-made Westerns, such as Old Shatterhand and other adventure yams. As Tita soon learned, he also came from a wealthy family and was a direct descendant of the founder of Rhode Island, Roger Williams.

In 1973, Barker suffered a fatal heart attack on a New York City street at age 54. Christopher Barker, one of the actor’s sons, contends that Tita pressed successfully for the bulk of her late husband’s $2 million estate in an out-of-court settlement in Geneva. Later, Christopher would tell Francesca that Tita had undertaken a campaign, over time, of replacing trustees for his father’s holdings with people sympathetic to her. Tita denies this and says she got nothing from Barker’s estate, which in any case, she claims, was far less than $2 million.

“Tita was in a very bad situation when Lex Barker died,” recalls one friend of the time. “She was in Capri with Fred Horowitz”—the same jeweler who would later introduce her to Heini—and looking into how to get her fair share of Barker’s estate, says the friend. Oddly enough, Sheldon Reynolds, Fiona’s former lover, was then a houseguest of Horowitz’s. He gave Tita the name of a lawyer in Los Angeles, Greg Bautzer, who was something of a lady-killer. Bautzer, in turn, introduced her to wheeler-dealer Kirk Kerkorian, with whom she became involved in a fairly serious affair that would taper into a friendship of 30 years.

Tita says that if she were a gold digger she would have married Kerkorian. Instead, she followed her heart and went with a Venezuelan movie producer named Espartaco Santoni. “He wasn’t dishonest,” recalls Vanity Fair contributing editor Reinaldo Herrera. “He just had no idea what money was. He threw it away.” A string of bad B movies all but bankrupted him and apparently left him desperate. Tita bailed him out of jail in Madrid but left him soon after. A few years later, she had a child out of wedlock: Borja. She never disclosed the name of the father. With Borja still a baby when she met Heini, she was, as the Spanish newspaper El Mundo put it, a woman “very few people would have placed their bets on.”

Tita’s arrival precipitated another messy period in the baron’s life. One day, Denise simply cleared out—reportedly with $80 million worth of jewelry. Heini actually sued for its return. One observer sympathetic to Heini says that $35 million of the jewels were either family jewels or valuables bought as investments. An observer sympathetic to Denise scoffs at that. “The jewelry had been given to her during the marriage. There was no family jewelry—if there had been, the sisters would have inherited it, right?” This observer says that much of the jewelry came as atonement. “[Heini] could get drunk and say foolish, angry things. Then he’d go out the next day and buy her jewelry as an apology.” After much legal wrangling, Denise got to keep the jewelry—and, by one report, also secured a settlement rumored to be in the neighborhood of $50 million.

Perhaps to keep any future wives from getting his assets, Heini, in 1983, put the whole of his Thyssen-Bomemisza Group, then worth $2 billion, into a Bermuda-based trust. “He was very, very aware of what his weaknesses were,” says Francesca. “He set these trusts up as a protection against his own self.” The Continuity Trust put his eldest son, Georg-Heinrich, in charge of the T.B.G. Heini no longer owned his business at all. By the terms of the trust, however, he would receive 30 percent of the T.B.G.’s profits, at least $20 million a year, assuming T.B.G.’s 100 companies did well. According to one close source, the children would get no money from the trust but would have incomes of their own.

Tita, not yet wife No. 5, was not represented in the Continuity Trust. Nor was Borja, though the baron would later adopt him, without bothering to tell his other children. When Tita did marry, she would be given by her grateful husband a 169-carat diamond called the Star of Peace, reportedly for not pressing a claim to the trust. (Tita says the diamond was just a gift.) Yet, more than a decade later, when the lawsuit was launched, its aim would be to break the Continuity Trust and put the T.B.G. into another trust—one controlled by Tita.

Before she got married, Tita’s one song, as Francesca puts it, was that Heini had not had real relationships with his children; she wanted to change all that. But when Francesca arrived for the wedding in 1985 at Daylesford, her father’s English country estate, she learned there was no room for her at the house. “That’s fine,” she said, knowing there were many small hotels in the area. “Where am I staying?” The nearby hotels, it turned out, were also filled with the couple’s social friends. Francesca was to stay in a hotel 90 minutes away—nearly the distance of her drive back to London. “I remember saying to myself there and then, Nothing has changed despite all her promises to keep the family together.”

In spite of his misadventures with Rappetti and Crispo, Heini had continued to collect with a passion. “Every New Year’s he’d resolve not to collect anymore,” says de Pury. “By January 3 or 4 that wish would be broken.” Now Tita was helping him, and the baron professed to be pleased. “Heini always told me, ‘You don’t have to learn art to understand painting,’” Tita recalls. “He said, ‘You need to have the eye.’ He said I had that.”

Denise all but gags at that. “Oh, come on! When Heini and I collected, we did it so seriously. It wasn’t a matter of ‘the eye.’ It was a matter of research—hard work!”

Since paintings were spilling out from the Villa Favorita and Heini’s other homes, some new large space would be needed to house them, but where? Heini’s first thought was to build an extension of the gallery at the Villa Favorita. As architects’ estimates climbed to $9 million, Heini asked the Swiss authorities to help; after all, the gallery would be a public space. “The attitude” was, recalls de Pury, “Well, the man is rich enough to pay for his own thing.” At that point, Heini began wondering if other countries might not be more obliging. And Tita began pushing for Spain.

A parade of eager dignitaries hastened to Lugano to make their pitches, including England’s Prince Charles and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. They offered a site on Canary Wharf, at that point London’s wild frontier. Heini was flattered but unpersuaded. Germany offered a space in Stuttgart, a city that held little interest for him. California’s Getty Museum offered lots of money, but only a wing, not a whole museum. Spain, on the other hand, offered the Villahermosa, a large palace in the center of Madrid. Tita and the baron were thrilled. The children, who had stood to inherit the art, were nonplussed. And so the battle began.

Both in private and in public, Tita declared that the children were betraying their father by balking at the Spanish deal. They had money already; they were just being greedy in refusing to let their father dispose of his art as he wished and wanting it for themselves. Francesca in particular she called an air-headed party girl. But the children stood firm, and so Spain agreed in 1988 to take the roughly 800 paintings in question as a loan, paying $5 million in annual rent for them for a period of 10 years with the hope that the paintings would later be made a permanent gift. The government also agreed to refurbish the Villahermosa for $45 million with, at Tita’s insistence, salmon-pink walls and white marble floors.

Some believed assurances were given to the government by the baron and Tita, despite the children’s refusal to sign. “After all, here they were spending $45 million on a building and another $50 million on rent. How could they have recouped that through entrance fees?” muses Roberto Shorto. “Also, once the pictures were in Spain, how would you get them to leave Spain? The government might not even give them back. The children had no real choice.”

Francesca and Georg-Heinrich felt that Tita cared only about reaping the social glory the deal would confer on her in Spain—including the title of duchess, which may have been dangled before her. For that, she was willing to hand over paintings worth $2 billion—for almost nothing. The children wanted something for them, given that the paintings represented a large part of their inheritance. They also wanted some say in how the collection was managed, not just during their lifetimes but in perpetuity. Georg-Heinrich, a lawyer by profession, began drafting terms. Slowly, the children started to come around.

Georg-Heinrich stayed low-key and non-confrontational. But between Tita and Francesca, tensions deepened. During the 1980s, Francesca had done her share of rebelling. But in working for her father at the Villa Favorita, she met the Dalai Lama and was transformed. Now she began curating shows of her own at the Villa Favorita—first of Tibetan art, then Islamic manuscripts. But on the eve of an opening, countermanding orders would come from Spain. A gallery agreed upon for a show—in which the art was already set up—would suddenly be deemed unsuitable. Corporate sponsors that had underwritten a show in exchange for being allowed to host a party for special clients at the villa would have to be told, at the last minute, the party was off. The edicts came “from the baron and baroness.” But Francesca felt sure who was behind them. And if she tried to call her father about them, he was never available. In frustration, she started her ARCH Foundation, to support art restoration. She also married Archduke Karl von Habsburg, grandson of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, which just happened to make her an archduchess.

In 1993 the children agreed at last to a deal with Spain. The government paid $350 million into a trust whose beneficiaries were the children and the baroness. (The baron himself got a small portion to pay off some debts.) As a sweetener to his first four children for accepting the deal, Heini formally agreed that, after his death, his 30 percent of the Continuity Trust’s profits would be divided among them. Neither Tita nor Borja was included in the deal, though both would share in the baron’s stake while he was alive.

The baron’s health, however, was deteriorating. In 1994 he lapsed into a coma after an artery operation and remained in it for 15 days. “When he came out of the coma, one side of his body was not working quite right,” Uta explains. “Though the mind was perfect.” This was debatable. At the least, the near-death experience seemed to make him fearful and more dependent on his wife.

One day in 1995 Tita marched into Georg-Heinrich’s office in Monaco and declared that her husband was very upset. He was accustomed to giving a lot of money to poor children, she said. But now he found there wasn’t enough money left over to give, because the Continuity Trust was sending him a fraction of the agreed-upon annual payment. Later, she toted up the shortfall and found it to be $69 million. She wanted Georg-Heinrich to disburse that immediately. Georg-Heinrich reminded her that the payment was dependent on profits from the T.B.G., and corporate profits were down.

Over the next months, lawyers for Tita and the baron pressed their demands. When the children gathered at the Villa Favorita in 1996 for the baron’s 75th birthday, the mood was tense. By one report, Georg-Heinrich stormed out. Tita scoffs at that. “The only thing that happened there was that Georg-Heinrich renounced his position on the Spanish [art] foundation.” Apparently, Georg-Heinrich suggested to his father that Francesca take his place until matters with Tita were resolved. The baron seemed amenable. “[Georg-Heinrich] wanted to put someone else,” Tita recalls airily, “and my husband didn’t agree on the person he wanted to put, so he put Alexander [Denise’s son] instead.”

To both sides, that was the last straw: from now on, lawyers would press the fight, profiting handsomely as they did. The war, declared Tita, had started.

The suit was heard in Bermuda, because that was where the Continuity Trust was based. In legal motions that began in early 1999, the baron’s lawyers accused Georg-Heinrich of “undue influence,” and said their client was owed $232 million—the figure had grown considerably since Tita’s first demand.

As the ranks of imported London lawyers on both sides grew, it became clear that no Bermuda court could hold them all. So the two parties paid almost $250,000 to have a Salvation Army hall converted into a suitable venue. In a sense, the baron also paid for the opposition’s defense, since Georg-Heinrich’s lawyers submitted their bills to the Continuity Trust. In all, the case would run up about $ 100 million in lawyers’ fees in order to prove, in the end, almost nothing.

For the British “silks,” it was a once-in-a-lifetime payday. Michael Crystal, the baron’s top barrister, began his opening address in October 1999. He finished 15 months later, after endless delays. The address involved examination of voluminous documents— 121,959 would be filed in all—and Crystal’s ruminations on his personal favorite painting in the Thyssen collection (a Mending). Tedious as his perorations were, Crystal spoke to an ever appreciative audience of fellow barristers: for all, duty away from home meant a 10 percent supplement, or “refresher,” to their already impressive rates of up to $1,500 an hour. When a reporter asked a young lawyer why he kept writing “ARTR” on his briefing papers each dreary morning, the lawyer explained what it meant: Always Remember the Refresher.

Neither the defendants nor the plaintiffs were in attendance and the lawyers soon traded their brogues and Savile Row suits for custom-made lightweight gowns and wraparound sunglasses. They rode around on motor scooters and frequented local bars, raising toasts to the baron. On weekends, their spouses often popped over from England, traveling business class at the baron’s expense. Crystal’s wife, Susan, became a fixture at the Bermuda airport, “dripping in jewelry,” as one newspaper report had it. Crystal and his colleague Robert Ham did make at least one effort to economize: they rented a mansion together for $15,000 a month.

As Crystal droned on into late 2000, some observers began to think the case might go on for five years, in which event, by some arcane law, the lawyers’ fees would be tax-exempt. The cost of the case was now said to be running about $540,000 a week.

On the baron’s fractious family, the human cost of the suit was, as Francesca puts it, “total destruction.” Georg-Heinrich had stopped speaking to his father. Francesca says she was cut off completely. When she called, she would be told the baron was asleep, or having lunch, or doing physical therapy. Once, she went to Madrid and rang at the gates of her father’s house. A longtime servant admitted on the intercom that if he let her in he would lose his job on the spot. Tita denies this. “He didn’t see Georg-Heinrich, because he had the lawsuit,” she says. “The other children could come ... anytime they wanted, and sometimes they came.”

The baron had become a somewhat pathetic figure. He still appeared occasionally at parties, but walked unsteadily, his paralyzed left arm in a sling. In 1999 one reporter found a bizarre scene at the house in Madrid. “The first thing Tita said was ‘I don’t talk for my husband. I’m not allowed to talk.’” But the baron, the reporter realized, could hardly speak at all. So Tita talked continuously for him. “This is my husband talking,” she kept explaining. The baron appeared weak and disoriented. At lunch he drooled. At one point he wandered away from the table and peed off the balcony.

Occasionally, friends would still visit. After dinner, Tita would excuse herself, and the friends, over a glass of port, would sometimes try to persuade the baron to abandon the suit against his son. Once, a guest walked into the next room to find an ashtray full of freshly stubbed butts: Tita, it seemed, had been eavesdropping. The friend was never invited back, and his subsequent calls were never put through. Tita laughingly denies this. “If we had friends over, we stayed together all evening, and anyone who wanted to see him was welcome.”

To sum up, Crystal told the court, the baron was misled about the way the trust was structured. So it should be changed and absorbed by the Vlaminck Trust—the trust that Tita controlled. In response, Georg-Heinrich’s lawyer Jeremy Sandelson archly observed that it was “frankly absurd to suggest that a man of [the baron’s] intellect and ability would not have got involved in the decision to effectively give away his business interests.” The defense had a dozen witnesses to attest to the baron’s presence of mind, and intent, in creating the trust as he’d done, not to mention all the papers he’d signed.

Sandelson raised another point that echoed loudly in Madrid. If the trust was dismantled, he said, the baron’s estate would be subject to Swiss law, which gave the heirs fixed rights. By that logic, the inheritance rights would come back into play and, in turn, jeopardize the Spanish art deal. The children might claim the paintings had been sold at a fraction of their worth: Spain might then have to pay much more for them or see the deal undone.

In Bermuda, Judge Denis Mitchell had heard enough. In March 2001 he told his court he was appalled by the trial’s obscene expense. “I was born and brought up in Scotland and taught a proper respect for money,” he railed. “It was not to be wasted.” Yet the judge also reportedly demanded that his own salary be almost tripled for him to continue to preside over the seemingly endless case. When the island’s government declined his request, Judge Mitchell astounded both sides by resigning. With that, the case ground to a standstill.

As the baron’s lawyers threatened to sue the Bermuda government for $15 million, they also began reaching out quietly to their counterparts to come to terms. For all the lucre, both sides were sick of the case and eager to go home. Talks went on through the fall, only to break down over Christmas. By then, the baron had had a heart attack. Now even Tita began pressing for peace: it was literally her husband’s dying wish.

On February 15, 2002, a flotilla of lawyers gathered in Basel, Switzerland, to sign a private family accord. In essence, the baron’s side had capitulated. The trust would stay as it was, with Georg-Heinrich in charge of it. The first four children would inherit much of their father’s 30 percent of the trust profits. Neither Tita nor Borja, according to one close observer, would get a share.

As originally outlined, the trust would expire in 2043. When it did, the assets of the Continuity Trust—which was to say the $2.7 billion T.B.G. empire—would be divided among the first four children, or their children. And because of the way the trust was set up, according to one report, none of the baron’s children or grandchildren would pay a dime in taxes. For each beneficiary, this was in addition to his or her share of the $350 million art trust, the balance of the baron’s collections, and other assets of his estate. The baron, though obviously frail, seemed relieved, even happy, to sign all the papers, though the seven hours it took exacted its toll.

All the children signed, with the exception of Alexander, much to his father’s distress. By one report, Alexander thus retained the right to “blow the structure away and attack everything,” which might yield him more money than the accord would. At 26, Alexander is said to be unusually close to his mother. “Denise won’t let him out of her sight,” says one friend. “She still lives with him.... She smothers him; he’s never allowed to do his own thing.” At the least, he appears to be acting in his mother’s interest as well as his own.

One by-product of the accord is that Francesca is now on the board of the Spanish foundation—the seat formerly denied her. Tita is on the board, too. The week before the first board meeting the two would attend together, Francesca visited her father in Barcelona. He was startled to see her; no one had bothered to tell him she was coming. Still, they had a good talk. He told her he wanted to go to Madrid with her to see the collection. He looked at her intensely. “Let’s go together in May!” he said.

On April 26, 2002, the baron was attached as usual to a defibrillator for the night. He was under 24-hour medical care at the Barcelona home where he had spent most of his last months with Tita—a home that Lex Barker had built for her on land she’d inherited from her father. “Give Juanita a kiss good night,” the baron said, referring to his favorite of Tita’s five little dogs. He and Tita discussed paintings, she recalls. Then she withdrew, and he went to sleep. At one A.M., he died, quietly, of a thrombosis.

At the first funeral, in Barcelona, all the children were present: an odd lot, made odder still by the presence of Borja, whom the others had just insisted on marginalizing in the final accord. Still, Borja is hardly a poor stepchild. He is sole heir to his mother’s share of the Spanish art deal and the rest of the collections. Presumably he will also inherit his mother’s personal collection of 800 paintings—including important Impressionist works—that the baron encouraged her to buy during their marriage. Borja also has a nascent art collection of his own, including a Goya given to him by the baron. For now, he has decided not to attend college, but instead to learn from his mother how to steward a private collection. At the Madrid house, he seems a sweet, shy young man, happy to hang out in the weight room with his bodyguard. His greatest passion, it seems, is cars. He owns a Mercedes SL and has just persuaded his mother to let him buy a Ferrari 360 Spider.

“He promised he would not drive fast,” Tita says, and for that moment her guard drops to reveal a very anxious mother.

“Not more than 300 [kilometers per hour, i.e., 188 m.p.h.],” Borja says with a grin.

After the memorial Mass in Madrid, mourners migrate to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza for a reception. One circle forms around Tita and Boija, another around Denise and Alexander, a third around Francesca. “One night my father found us dancing on that rug,” Francesca says of a huge Oriental carpet exhibited on a wall beside her. “He said, ‘You’re not going to ruin my carpet!’ and rolled it up himself.” This was years ago, at the Villa Favorita, when Denise was Francesca’s stepmother. “Oh,” Denise says when asked about the story, “that’s not how it happened at all.”

More revealing than who’s here is who’s not: Teresa and her son Geoig-Heinrich, Fiona and her son, Lorne. Madrid is Tita’s venue, so they have shunned it. Besides, the whole brood has already assembled once, in Germany, for the baron’s interment in his family vault—near the bones of the father he never felt he pleased, and the grandfather whom his father probably never pleased, either. In pictures from that extraordinary gathering, the three surviving ex-wives and Tita look beautiful still. Fiona reportedly has a younger Greek boyfriend and divides her time between Greece and Switzerland. Lome converted to Islam, years ago, and works as an actor and film producer. Denise also has a beau, and divides her time between Rome and Sardinia. Teresa of Lippe has remarried, to Prince Friedrich zu Furstenberg. All the wives, Tita reports, had “very good manners. We kissed each other.”

Tita thinks the peace will hold. “Everything is very well understood,” she says. Francesca thinks so, too, though that may only be because Tita has no gambits left to play. Yet just a week after the memorial Mass in Madrid, sparks are flying again between the widow and the baron’s daughter. A commemorative party has been arranged by the baron’s children at the Villa Favorita—a party for longtime friends not part of Tita’s circles in Spain. Tita is saying the children can’t use the Villa Favorita for it. “She has alienated so many of these people over the years, I think she’s just terrified of facing them now,” says Francesca. But Tita has her own version. She says the house is in turmoil because all the art in it—paintings, furniture, and other collectibles, none of it sold to Spain—is being packed up for the children, to whom it was parceled out by rotation at the time of the Spanish deal. “I said, ‘It’s all your furniture we’re packing, that won’t look good.’ So we had the reception in the gallery, and it was fine.”

The packing denotes a larger contretemps. Tita says she plans to sell the Villa Favorita. Why, she suggests, would she want to be there without her husband? The children could buy it, she says, but adds that they have declined to do so. A week later, Spanish tabloids trumpet the news. In print, it makes Tita look callous. Days later, she has her press secretary declare that the baroness has no intention of selling the villa. “I want to keep it, at least for a while,” she says. “It’s a romantic thought.”

Meanwhile, the children, after deploring Tita’s earlier plan to sell the villa, are cashing in family goods of their own. Six paintings from the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection said to belong to Francesca, including a Camille Pissarro estimated to fetch up to $2.2 million, have just been put up for auction through the baron’s old curator Simon de Pury at Phillips de Pury & Luxembourg in London. Legacies are lovely, but like everything else, it seems, they can be sold if the price is right.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now