Sign In to Your Account

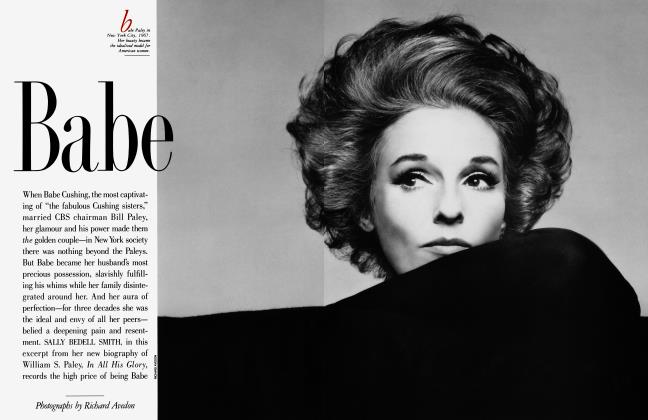

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMean for Jesus

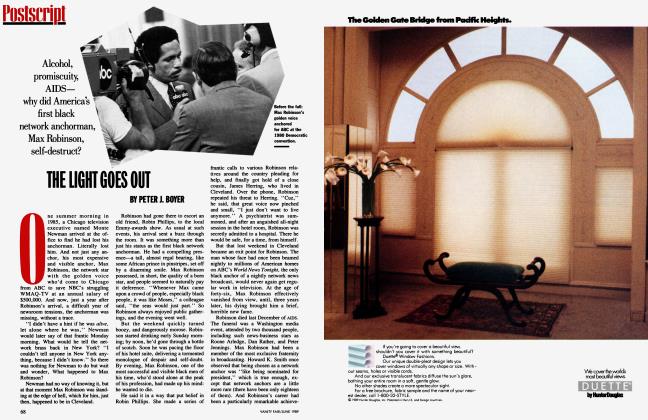

Jesse Helms, for eighteen years the Bible-thumping scourge of the Senate, is suddenly facing a changing world and a tough race against Harvey Gantt, the black former mayor of Charlotte. Just as it looked as if Helms might finally be out of steam, along came Piss Christ, in an exhibition funded by the N.E.A., to put him back on a holy roll. PETER J. BOYER reports how the senator is making headlines turning an esoteric nonissue into a down-home crusade— while North Carolina sinks into poverty and neglect. But will voters buy the Helms agenda again?

PETER J. BOYER

t is hot inside the Carolina Tobacco Warehouse, entirely too hot to endure much more of a local candidate's numbing drone, and the eight hundred or so folks at the friendly political gathering do something a bit rash—they hoot the unfortunate fellow back to his seat, hastening the main event.

And the main event, Jesse Alexander Helms, doesn't disappoint. He moves to the podium, carried by a seismic welcome, and briefly acknowledges the ladies on the stage (the bed of an eighteen-wheeler, adapted for the occasion). Then, framed by the huge floor-to-ceiling American flag behind him, as in the opening scene from one of his favorite movies, Patton, Jesse Helms does what he does best. He tells a story.

"You ask if anybody had a hard week,'' he begins. "You really wanna know? I wish you could see some of the mail I'm getting. I got a letter from a 'lady'—and I use the word advisedly—in San Francisco, and that tells you something to start with, and she really ate my lunch." His basso profundo, tailored by a lifetime of Lucky Strikes and a broadcaster's instincts, perfectly fits the rolling curves of his deep-Carolina drawl, filling the spaces of the big tin warehouse. "She didn't like anything about Jesse Helms. As a matter of fact, she closed by saying, 'Every time I think of your name, I throw up.' So I wrote her back. I said, 'Dear lady, you may be onto something. The next time it happens, frame it and send it to the National Endowment for the Arts and they'll give you $5,000 for it.' "

Helms steps back and accepts payment, a loud, long, approving roar. Art jokes aren't exactly a staple on the barbecue-and-iced-tea circuit, where federal arts-funding policy is a less pressing issue than, say, farm-price supports. Many of the folks at this Goldsboro rally, tobacco farmers and preachers of the Gospel mostly, never heard of or didn't much care about the National Endowment for the Arts until Jesse told them they should—and that's the point. Jesse they know. For eighteen years, he's been their avenging angel in Washington, fighting the infidels and sinners, often alone, never giving an inch. He is a dragon slayer in a world of accommodators, and for most of them, that's good enough.

But dragon slayers need dragons, and Helms has been running out of them. With Ortega gone and the Berlin wall down, Helms's enemies began to hope that, as he faces reelection this fall, history may have finally made him irrelevant. With his remarkably high negative ratings, no Helms re-election is ever easy. "Let me tell you," Helms tells the Goldsboro faithful, "Jesse ain't got it made. The other side could nominate Mortimer Snerd and he'd get 40 to 45 percent of the vote in November, right off the top."

So the controversial art that Helms denounces on the Senate floor as blasphemous filth is really more like a heavenly gift, neatly wrapped and delivered to Helms's door at just the moment he needs it. It allows Jesse to be Jesse, to clear away the fuzzy abstractions (such as freedom of expression) and ask, as he asks in Goldsboro, "How about a federal agency that rewards and subsidizes filth and blasphemous so-called art designed to promote homosexual conduct using the taxpayer's money? How do you like that?" It allows him to gleefully maneuver his Senate colleagues into awkward contortions. It allows his potent direct-mail operation to urgently solicit money from its list of more than 450,000 names in the cause of fighting anti-Christian art. The issue has, in short, allowed Helms to create his own political masterpiece, a classic of American demagoguery.

Along the way, he has cast the arts endowment into the worst crisis in its twenty-five years, forced the White House into an embarrassing retreat on the issue, and provided an object lesson in the sound-bite mentality of made-for-TV politics. Liberal activists are discovering, to their dismay, a notable absence of champions on the other side of the issue. Norman Lear's People for the American Way has raised money and lined up celebrities in order to provide "Jesse insurance"—slick campaign ads featuring Hollywood-star endorsements—for senators willing to challenge Helms; so far there have been no takers. One Democratic senator—who has had presidential aspirations—insisted that his meetings with the anti-Helms lobby be conducted in secret. When Helms pushed through his 1989 anti-obscenity amendment, requiring artists accepting public funds to sign an oath of decent intent, most of the star liberals—like Teddy Kennedy, Howard Metzenbaum, even "the father of the N.E.A.," Claiborne Pell— were absent, quiet, or effectively acquiescent.

"I'm not a politician," Helms tells the Goldsboro crowd, and "I don't know how to do this political business," and his supporters know that he means more than campaignspeech humility. Jesse Helms may well be the only member of the U.S. Senate who doesn't secretly believe he can please all the people all of the time, or even seem to be pleasing them. He is a brilliant political operator largely because he is the consummate anti-politician: he's wrong, perhaps, maybe even dangerous, but he is always unwavering, and certain.

And that is why Jesse Helms, in what may be his most vulnerable moment in public office, is winning, and the National Endowment for the Arts and all of its friends are not.

y the way, it was never a jar of urine," Andres Serrano says with a trace of indignation. "It's an actual tank, built specifically for that photograph."

"That photograph," of course, is the one that launched the war over the arts: the image of a crucifix submerged in urine, which Serrano titled Piss Christ. When Jesse Helms denounced Serrano and his photograph on the floor of the United States Senate in 1989 ("He is not an artist, he is a jerk"), thereby guaranteeing the littleknown artist instant celebrity, he described the creative process thus: "What this Serrano fellow did, he filled ajar

Piss Christ came very close to missing its

with his own urine and then stuck a crucifix down there—

Jesus Christ on a cross. He set it up on a table and took a picture of it."

Actually, Serrano says, ajar would have been impossible. "I mean, ajar—I can't see how you can photograph through ajar, since it's round." It was a Plexiglas tank, twelve by eighteen inches, holding "maybe four gallons of fluid, tops."

Piss Christ came very close to missing its date with political destiny. It was created in 1987, when Serrano was asking himself, Have I gone far enough? A lapsed Catholic, he'd been partial to body fluids, with a particular leaning toward blood, and also worked heavily with religious themes. Piss Christ, he says, seemed a way to meld the two urges into one work.

The crucifix was easy; his Brooklyn studio was loaded with them.

Filling the four-gallon tank was another matter: "I saved it up for a couple of weeks."

That accomplished,

Serrano made the photograph, and was quite pleased with his achievement. "I think it's charged with electricity visually," he says. "It's a very spiritually, I would say, comforting image, not

unlike the icons we see in church, you know? There is, I think, a very reverential treatment of the image. At the same time, the fact that you know there's a bodily fluid involved here.. .it's meant to question the whole notion of what is acceptable and unacceptable. There's a duality here, of good and evil, life and death."

Art? Sacrilege? Or merely the look-at-me indulgence of a downtown fraud who peed on Jesus? For a time, it seemed as if it might not matter. When Serrano displayed the photograph at Stux, the Spring Street gallery, it prompted only one comment—from a minister's wife, who, Serrano says, claimed to share the artist's apparent ambivalence toward organized religion.

But later that year, Serrano was one of ten artists selected to share in the annual Awards in the Visual Arts, a wellregarded program that is administered by the Southeastern

Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The program, which was underwritten by the Rockefeller Foundation, Equitable Life Assurance, and the N.E.A., granted each artist $15,000 and sponsored a

three-city tour of their work. Serrano's eight-piece exhibi-

tion, including Piss Christ, was shown in Pittsburgh and L.A. without a fuss. And then it went to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in Richmond, where one Saturday afternoon early last year it was seen by Philip L. Smith, a fortythree-year-old computer designer, who was quick to pick up on Serrano's implicit invitation to "question the whole notion of what is acceptable and unacceptable."

"I just couldn't believe they would have that in a museum," Smith says. He was so outraged that he didn't even wait to get home to complain; he stopped by the museum's information desk ("The man at the desk said he was offended, too"), borrowed a piece of paper, and wrote a note

to the museum's direc-

tor, Paul N. Perrot. When Perrot's written response proved unsatisfactory, Smith decided to write to the editor of the Richmond TimesDispatch. With the help of his wife and a friend from their nondenominational Fundamentalist church, Smith composed a three-paragraph complaint that asked, "Would they pay the KKK to do a work defaming blacks? Would they display a Jewish symbol under urine? Has Christianity become fair game in our society for any kind of blasphemy and slander?"

date with political destiny

The paper published the letter on a Sunday, setting a time bomb beneath the National Endowment for the Arts.

mith's letter was read by a Richmond follower of the Reverend Donald Wildmon, a Tupelo, Mississippi, Fundamentalist preacher who sees America as the stake in a values war between the godly and the godless, which is to say that his worldview is precisely that of Senator Jesse Helms. Wildmon's battleground is the popular culture, and his Christian-soldiering goes back at least to the early 1980s, when he headed an organization called the Coalition for Better Television, a group that monitored network television programs. At one point, Wildmon's group boycotted an entire network— NBC—where he was taken seriously enough to be accorded regular access to the executive suites. His main organization, the American Family Association, became a powerful grassroots mobilizing force, claiming 570 chapters nationwide and a sophisticated computerized direct-mail list of 425,000 people—a substantial number of whom volunteer their free

time to scan the landscape for signs of heathenism. In the mid-eighties, Wildmon forced the Southland Corporation to remove Penthouse and Playboy from convenience-store shelves; in 1988, he led the noisy fight to kill The Last Temptation of Christ.

And in late March 1989, the Reverend Mr. Wildmon laid eyes on something he could scarcely believe—a catalogue from the Virginia Museum containing Serrano's Piss Christ. He unleashed his army, and Equitable Life Assurance was soon bombarded with 40,000 letters. More significant, he sent a photocopy of the picture with a letter of protest to every member of Congress.

Even then, Helms almost missed the issue. The staffer in his Washington office who opened Wildmon's letter dismissed it without much thought. Two congressmen, Richard Armey of Texas and Dana Rohrabacher of California, made some noise in the House, but in the Senate, oddly enough, the only dander noticeably aroused was that of Alfonse D'Amato of New York. Ignoring, or perhaps forgetting, that roughly forty cents of every dollar granted by the N.E.A. goes to New York, D'Amato planned a frontal assault on the agency. Hearing of this, a Helms aide named John Mashbum, fearing that his man was missing out on a perfect issue, hurriedly worked to get his boss up to speed. Mashbum telephoned Ted Potter, the director of SECCA, the WinstonSalem institution that had honored Serrano's work. Potter recalls that Mashbum told him of D'Amato's plans to denounce Serrano and his work, "and he said the senator [Helms] wanted to help us. Basically, he asked what the program was about, things like that, how much endowment funding we received. And he was our senator, so we gave it to him over the phone."

Mashbum fed the information he'd gotten from Potter to Helms, who was outraged. The next day, May 18, D'Amato took to the Senate floor and put on a show, ripping the Serrano catalogue, hurling it to the ground and stomping on it. Noting that some of the $15,000 awarded to Serrano came from the N.E.A., he said that he and the other senators deserve the public wrath "unless we do something to change this."

D'Amato was followed by Helms, who was characteristically more eloquent, if less antic, than the senator from New York. "I am not going to call the name that [Serrano] applied to this work of art," Helms said. "In naming it, he was taunting the American people. He was seeking to create indignation. That is all right for him to be a jerk, but let him be a jerk on his own time and with his own resources. Do not dishonor our Lord."

Helms supporters soon received a mailing: "Please rush Jesse Helms a special contribution of $29 today!" the letter said. "He needs you to support his legislation to stop the liberals from spending taxpayers' money on perverted, deviant art!"

The war was on.

Pell has the tone of a man accustomed

Back in North Carolina, those who've seen the power and sometimes felt the sting of Jesse Helms's brand of politics have applied to his mission the nickname "Mean for Jesus.'' Indeed, Helms's religion—hard-shell, Fundamentalist, born-again Southern Baptist Christianity—is bound up inseparably with his politics, at once its wellspring and its rationale. If Helms's vision of America is exclusionary (as demonstrated by his battles against school integration and the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday) or intolerant (his relentless attacks against homosexuals) or lacking compassion (his "brought it on themselves'' tirades against people with AIDS), it is because his religious sensibility is attuned to the Old Testament, with its emphasis on a wrathful God given to destroying wayward cities by flood and fire. "Sinfulness must not be condoned by anyone who wants this country to survive'' is Helms's constant refrain.

His beliefs were forged in Monroe, North Carolina, a town of three thousand souls in the small-plot cotton farmland of the Carolina Piedmont, which Helmses of one branch or another had occupied for almost two hundred years. When Jesse Alexander Helms Jr. was born there in 1921, Monroe was a town with more churches (five) than registered Republicans (four). Jesse senior,

"Mr. Jesse," as he was known, was a nononsense disciplinarian, the town's police chief and fireman. At six feet five, he represented the firm hand of the law literally and figuratively for both young Jesse and the townsfolk.

Growing up in such a town at such a time was an experience that lent itself to the easy adoption of absolutes (southerners are born Democrats, the races are separate, Wednesday night is for prayer meeting, and God helps those who help themselves) and intense sentimental impressions (ice wagons, swimming holes, and Saturday matinees). Together, those absolutes and those impressions formed a powerful emotional pack-

age, an image of what life was and should be, which young Jesse packed up and took with him out into the world, like a salesman hell-bent on getting his foot in America's door. It was much the same pattern and motivation that drove Ronald Reagan, who would come to sell his nostalgic package of a Christian America as experienced in small-town Illinois.

Like Reagan, Helms left home in small steps, going first to a small Baptist college nearby. He transferred to Wake Forest College (where, he later allowed, he took no art courses) before dropping out to become a reporter at the Raleigh News and Observer, where he met and married the editor of the women's page, Dorothy Coble. But his true

calling, and natural love, was broadcasting, a field in which he would develop a political base and refine the skills that have made him one of the great communicators of his time.

In 1948, at the age of twenty-seven, Helms was hired by an archconservative businessman named A. J. Fletcher to join Fletcher's new, 250-watt Raleigh radio station, WRAL. He gained entree into national politics when he left WRAL to join the Washington staff of North Carolina's new senator, Willis Smith. But Smith died in office shortly thereafter, and so Helms returned to Raleigh, taking a job as director of the state's bankers' association. He padded his nest, laid ties to the social and business establishments—and added a firm free-enterprise plank to his political vision. He and Dot had two daughters, and adopted a son, Charles, after reading a newspaper story about a nine-year-old Greensboro boy with cerebral palsy who wanted nothing for Christmas but a mother and father.

Professionally, Helms was comfortable, but he was not completely content. He still had that vision to sell, and although the bankers' association allowed him a signed editorial in its trade paper and he'd won a city-council seat, he longed for the more potent voice of broadcasting. He got it in 1960, when his old mentor, A. J. Fletcher, got a television license for WRAL and hired Helms to be the station's (Continued on page 264) (Continued from page 229) editorialist. The roiling 1960s provided the perfect setting for Helms's handiwork. Every evening during the six-o'clock news, he delivered a five-minute "Viewpoint," laying into the infidels: The campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was a nest of pinkos, where Communists were working their will "through subversion, through espionage, through poisoning the intellectual climate." The civil-rights movement was led by "professional agitators, opportunistic charlatans, and political phonies." And Martin Luther King Jr., a favorite target even in death, associated with "Communists and sex perverts."

to addressing butlers.

As the voice of the only TV station in North Carolina's capital, Helms instantly gained the stature (as well as the bitterly divided attention of his fellow citizens) that made him a natural candidate for statewide office, and two years after switching to the Republican Party in 1970, he ran for the U.S. Senate. Helms would protest then, as he does now, that he entered politics reluctantly and clumsily ("Gosh, I was the lousiest candidate, still am," he recently told a group of supporters), but his canny, slashing campaign style was there from the start. Helms's opponent in that first race was Nick Galifianakis, a congressman of Greek ancestry, a fact that Helms's campaign exploited with the unsubtle slogan Jesse Helms: He's One of Us. With the support of Richard Nixon and the help of an incredibly advanced fund-raising machine, Helms became the first Republican senator from North Carolina since 1895.

r 11wenty years earlier, during his first A stay in Washington, Helms had learned his single most valuable political lesson, from Senator Richard Russell, architect of the South's segregationist parliamentary tactics. "Jesse," Russell told him, "a senator who does not know the rules can be cut to ribbons by a senator who does." Now Helms took the message to heart. Under the tutelage of Alabama's James Allen, he studied the procedural rules, spending long hours in the presiding chair, like a schoolboy staying after class, until he knew more about how the Senate worked than almost anyone else.

He used this knowledge to establish himself as a kind of legislative guerrilla, and his colleagues in the Senate didn't quite know what to make of him. He seemed, on the surface, something quite familiar—another hidebound southern politician—but he was also something quite new. Unlike John Stennis of Mississippi, or, for that matter, Senators Allen and Russell, who knew that the Senate was a club with certain protocols and unspoken rules (chief among them being "Thou Shalt Not Embarrass Thy Fellow Senators"), Helms was there not to serve a constituency but to serve his vision. He refused to join the club.

With the exception of some tobacco legislation, his floor work consisted mostly of pursuing his own lonely, quixotic, and usually doomed agenda. He fought busing and federal aid to Vietnamese refugees; he fought Nixon appointees and Reagan appointees (trying to block Caspar Weinberger's nomination as secretary of defense because he hadn't shown himself to be tough enough on the Soviets); he fought Gerald Ford's selection of Nelson Rockefeller as vice president, saying, "He stole another man's wife."

The Raleigh News and Observer dubbed him "Senator 'No,' " a title he gladly adopted as a sign of achievement. But he didn't only say no. Using the Senate rules allowing any senator to introduce any amendment, germane or not% to any piece of legislation on the floor, he peppered his colleagues with amendments they'd already stopped in committee.

"So you're sitting here discussing the appropriations legislation or some military bill or something like that and all of a sudden you're voting on abortion... for the nine-hundredth time, by the way," as one Helms opponent describes it.

Where playing by the unspoken rules allows senators to quietly dispense with emotional issues on which they personally disagree with their constituents, Helms's method often forces a public accounting of such decisions. That tactic is how he won a federal ban on the immigration of people who are HIV-positive, even though the Bush administration concedes it's probably unfair; it is how he pushed through bills that restored Oliver North's pension, limited dial-a-pom services, and blocked special federal housing funds for AIDS patients.

None of this, of course, has endeared him to the other senators. "He takes a lot of heat," says Carter Wrenn, who runs the Congressional Club, Helms's fundraising operation in Raleigh. "I remember when he was fighting the gas tax back in Christmas of '82 and Alan Simpson got mad at him and had some things to say. I don't think he's immune to that sort of thing emotionally. I don't think anybody ever gets so tough and coarsened that it just doesn't affect 'em."

The confrontation with Simpson was memorable. Helms, opposing a nickel-agallon tax increase that his own party was trying to pass, kept the Senate in knots for twelve days with a filibuster, holding up the Christmas recess. Worse, he vowed to keep them there through Christmas if that was what it took. In the early-morning hours of the thirteenth day, after a particularly heated floor exchange in which Simpson, a Wyoming Republican, called Helms's performance "obnoxious," Helms approached Simpson at his desk and offered his hand, saying, "Let's be friends." And Simpson, considered a gentleman, refused to shake, refused to speak. He just sat there, staring at Helms. It was, some senators said, an act of enmity none had ever before witnessed in the branch of Congress known for its clubby comity.

But then, Helms shows no particular need for Washington's embrace. He was fifty-one, his children grown, by the time he became a senator, and the life-style that he and Dot have chosen is unlikely to tempt him from the path of righteousness. They don't party, they don't drink. In the used Oldsmobiles he's partial to, Helms drives himself to and from his Arlington home, which, like his house in Raleigh, is wholly unpretentious—"ancient fill-in'' is how he once described the decor.

At home, he slips into a pair of old slacks and running shoes, and often settles down to write letters on an ancient typewriter, banging away in the old huntand-peck method of his newspapering years. He has no hobbies to speak of, and he and Dot don't even go to the movies, for fear they'll be confronted with new evidence of a society bound for damnation. ("I haven't seen but one movie in three years, and that was Driving Miss Daisy," he says. "And she didn't hop into bed with anybody.") A typical night at the Helmses' ends in front of the TV, until the sexy stuff gets to be too much for Dot.

"The other night, they started that stuff and she said, 'Oh, for goodness' sakes,' and I said, 'Turn it off!' " Helms recounts. "Now, I say again, we're not prudes. But I think we oughta draw the line, lest we become part of what we condone."

Helms can be the essence of Old World southern charm, a door opener and a hat doffer of the first order. John Frohnmayer, the new chairman of the N.E.A., was so impressed after his first meeting with Helms that he said, "I found him to be an extremely fine, gentlemanly person. I don't think that there is anybody that I've met on the Hill who is more of a gentleman in person." In the coming weeks, Helms and his allies would proceed to take Frohnmayer apart, one limb at a time, until he retreated to the sanctuary of his agency, refusing to speak even to the press.

T n the two months following the denunJciation of Serrano by D'Amato and Helms on the Senate floor, Robert Mapplethorpe became part of the arts fray, and Senator D'Amato dropped out. The controversial Mapplethorpe, who'd died that spring of AIDS, entered the picture when a portfolio of his photographs was featured by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, partially funded by the N.E.A. The show included a lot of pictures of flowers, but it also included photographs with homosexual themes—an array of penises, leather-clad men in chains, and some shots that were, even in context, particularly rough and explicit. That guaranteed notice from Wildmon, Rohrabacher, and company, and gave Helms new ammunition.

As for D'Amato, the man who had launched the war on the N.E.A. from the Senate floor quietly retreated. "I think he's changed his tune," says Kitty Carlisle Hart, one of New York's heavyweight art patrons. ''We went and talked to him," Mrs. Hart recalls, ''and explained that it was really a stand that was not appropriate to New York."

But Senator Helms, not so easily swayed, quietly proceeded with his plans to shackle the endowment. John Mashbum went to work on an amendment that his boss could attach to the appropriations bill funding the N.E.A. for 1990. That bill already included a rather startling provision that would limit funds to the two institutions, SECCA and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, that had put up the Serrano and Mapplethorpe shows. Helms's amendment would go much further: it would prevent the N.E.A. from supporting any ''obscene or indecent materials, including but not limited to depictions of sado-masochism, homo-eroticism, the exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts; or material which denigrates the objects or beliefs of the adherents of a particular religion or non-religion; or material which denigrates, debases, or reviles a person, group, or class of citizens on the basis of race, creed, sex, handicap, age, or national origin."

On the night of July 26, 1989, Helms went to the floor of the Senate with no advance warning to anyone but Robert Byrd of West Virginia. Helms knew that Byrd, as a powerful Democrat and shepherd of the appropriations bill, could force a roll-call vote on the amendment. So he brought along a little insurance, in the form of Mr. 10½.

Mr. 10½ was a Mapplethorpe photograph that drew its title from the extravagant endowment of its subject. Before introducing his amendment, Helms walked over to Byrd, explained his intentions, and said, "You have to see this to believe it." He then showed Byrd the photograph; he also showed him two Mapplethorpe photos of children with exposed genitalia, and another shot, Man in Polyester Suit, in which the polyester suit, unzipped at the fly, was the least noticeable element.

"Whoa!" Byrd said as he viewed the photographs. "We funded that? I'll accept your amendment."

Essentially, Byrd's agreement to a voice vote on the amendment let his fellow legislators off the hook. Any senator present could have insisted upon a floor fight and a roll-call vote that might well have killed Helms's measure. But, after introducing the amendment, Helms enunciated a compelling threat: "If senators want the federal government funding pornography, sadomasochism, or art for pedophiles, they should vote against my amendment. However, if they think most voters and taxpayers are offended by federal support for such art, they should vote for my amendment."

Only one senator, Republican John Chafee of Rhode Island, rose to oppose Helms's amendment on the record.

The voice vote was called; the amendment passed quickly and quietly. And then the liberal brigade paraded through. Senator Kennedy delivered a speech extolling the virtues of the N.E.A., and defending the endowment's peer-review system. He then had twenty letters from members of the arts community supporting the N.E.A. read into the record. Senator Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island, the liberal Democrat who'd helped to create the N.E.A. in 1965, also rose to warn that Helms's amendment "moves us ever closer to government censorship." But neither speech amounted to more than window dressing. "Byrd said to people like Pell and Kennedy and the liberals, 'Let's just take it now and we'll work out what bothers us in conference,' " says one Senate staffer.

"It was a shock to us," says Barbara Handeman, of People for the American Way. Arts lobbyists were told by friendly senators that the amendment was just part of the annual appropriations process, that the real battle would occur in the next year's session, when the arts agency's five-year authorization, its right to exist, had to be decided. "But of course the Helms amendment sent a message," Handeman says. "It kept the thing alive."

By the time the amendment became law, it had been watered down to the point where Helms considered it no longer effective, but most in the arts community thought it was entirely too effective. For the first time, artists and art institutions had to sign an oath vowing decent intent. "It awakens ancient fears," says Kitty Carlisle Hart. "The signing of oaths reminds people of McCarthy times." It was loathsome enough to some, such as director Joseph Papp and the Paris Review, to cause them to turn down N.E.A. grants.

Helms's victory was his ability to define the terms of debate—a Helms trademark. By the time the reauthorization fight began this summer, the assumption on all sides was that there would be some restrictions placed on the N.E.A.; the only question was how severe they would be.

T f anyone should have been the champiX on of the arts endowment, it was Claiborne Pell, who in some regards seems cast by nature as Helms's proper adversary in the arts fight. Pell is in every way Helms's opposite: eastern blue blood, liberal Democrat, Ivy League establishment. And he has an abiding interest in the arts, having spent his first four years in the Senate, 1961-65, laying the groundwork for the creation of the N.E.A. He chairs the Senate subcommittee that gives the endowment new life every five years.

But Pell is as conciliatory as Helms is confrontational, as eager for consensus as Helms is willing to fight the lonely battle. Where Helms has stood at the edges of the Club, throwing rocks, Pell has been inside, presiding over tea. "My relations with Senator Helms are correct," he once said, as if at the end of the day, good form is what counts the most.

Although Pell is a Newport aristocrat, the largely blue-collar voters of Rhode Island have habitually sent him back to the Senate since 1960, even in the Republican-presidential-landslide years of Nixon and Reagan, as if his Senate seat were his inheritance, which it almost is. Five Pell ancestors served in Congress, including his father, who was a one-term congressman from Manhattan's "Silk Stocking" district.

In a milieu increasingly populated by people who look and sound like local TV anchormen, Pell, like Helms, stands out as an extreme. Pell has the countenance and tone of one who is accustomed to addressing butlers. When The New York Times asked his opinion a few years ago of then secretary of state George Shultz's role in foreign policy, Pell said, "My impression of Shultz is very high; I didn't know him at college. He was two years behind me. Princeton." An often told story about Pell recalls an occasion when he was campaigning up in Rhode Island during a terrible storm: his shoes were getting wet, so an aide was dispatched to fetch him some galoshes.

"To whom," Pell asked the obliging aide when he returned, "am I indebted for these?"

"I got them at Thom Me An's."

"Well," Pell said, "do tell Mr. McAn that I'm much obliged to him."

In the Senate, Pell's interests have generally reflected his personality—education, ocean research, the arts, issues that have not been (until recently) hotly contested—and he is sometimes gently chided for his "bird-watcher's agenda." He's long had an interest in psychic phenomena, and has an assistant, C. B. Scott Jones, who spends time researching telepathy, unconventional healing, and neardeath experiences for the senator. While regarded as a serious intellect, Pell gives the impression of being absentminded, even slightly befuddled. One busy morning a few years ago, he dashed into a Senate hearing room and began reading a statement about federal scholarships for underprivileged students, a program called the Pell Grants, in honor of his stewardship. After a few moments, Howard Metzenbaum whispered into Pell's ear. The Rhode Island senator said, "I apologize deeply," and left. He'd walked into the wrong hearing.

Claiborne Pell's personality is distinctly cool, diffident, so much so that some have given him the unkind nickname "Stillborn Pell." Where Helms frames each of his special issues as a choice between salvation and imminent destruction, Pell once said of himself, "I have this unfortunate facility, perhaps, of making the most exciting subject gray."

That lack of dynamism caused concern among some Democrats when he became chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee in 1987, not least because the ranking Republican is none other than Jesse Helms. Nowhere is their mismatch more apparent than on that committee, where Helms runs wild while Pell sits and worries about quorums. Absenteeism is chronic, and the committee has suffered such a prestige loss that young senators fight to stay off it.

In Pell's first year as chairman, Helms so freely exerted his presence that the committee's more assertive Democrats— Paul Sarbanes, Christopher Dodd, Joe Biden, and Alan Cranston—took it upon themselves to form a kind of vigilante band called "Helms Watch." They'd take turns monitoring Helms—making notes, paying attention—and deflect or delay him when he began to take charge of the hearing. Helms Watch remains on alert today. "It's not so much a comment on the chairman personally, but on his style," one Senate staffer explains. "Pell, as you know, comes much more out of the old gentlemanly school, and Helms will often put on that air—he will be deferential to his colleagues—while he's cutting 'em off at the knees."

In one recent session, Helms, who was sitting to Pell's right at the committee table, expressed sweetly that "it's a pleasure to work with the chairman," and then began to tear into the committee's version of a bill authorizing State Department funds. Sarbanes, sitting to Pell's left, defended the chairman's version, and back and forth they went, arguing literally over Pell, who sat silent. Finally, Sarbanes ended the discussion by saying, pointedly, that "the chairman, as usual, in almost an excess of fairness, as is his characteristic," had had the bill floating around the committee plenty long enough to give everyone a chance to address it.

A few moments later, Republican Rudy Boschwitz of Minnesota gathered his things, got up, and headed for the door. Pell, alarmed, said to him, "You'll break our quorum."

"Good!" snapped Boschwitz. "Why don't you bring some more Democrats next time?" And he left.

Co while it has fallen to Pell to carry the ^endowment's cause in the Senate, the mantle of leadership on the arts issue has gone to Congressman Pat Williams, a Montana Democrat who chairs the subcommittee charged with reauthorizing the N.E.A. on the House side. It was Williams who was most vocal in his support for the endowment in the long months leading up to the reauthorization fight, and it was Williams's hearings that attracted the attention of both sides. And it was Williams who took the heat, as attested to by the level of choler in Tim Wildmon's assessment of him. The Reverend Donald Wildmon's son, who is associate director of the A.F.A., says, "You ask the average taxpayer walking down the street, 'Do you think that your tax dollars should go to pay for this?' And you show him Mapplethorpe with this bullwhip stuck up his tail, or.. .homosexuals engaged in sex, and I'm not talking about veiled, I'm talking about out-and-out penetration, then I think they're gonna say no.... Pat Williams, though, is saying the taxpayers oughta be forced to continue to pay for that."

The A.F.A. threatened to send 1,600 copies of explicit homoerotic photographs to churches in Montana, and an editorial in the Montana Standard demanded that Williams show the people just what pictures he was defending. "Except for Williams," Tim Wildmon says, displaying an astute understanding of the political climate, "I haven't heard anything of people taking the cheerleaders' position for the continuation of N.E.A. without any restrictions. How do you defend one man urinating in another man's mouth, like in the Mapplethorpe?... Even if [legislators] are pro-N.E.A., they're not going to stick their political neck out to fund this kind of stuff. ' '

Williams says that he gladly accepts the chance to stand up for freedom of expression, that anybody in his shoes would have done it. He does allow, though, that he wishes Pell and his colleagues had tried to stop Helms in the Senate a year ago. "I think it was easier [for them] to fight another day, at that point," he says. "They knew the House would try to take care of it, and they dumped a very difficult load on me."

Pell admits that he, Kennedy, and the other N.E.A. supporters should have tried to head off Helms then. "It was in the evening, and I think the general feeling was, just frankly, there was not enough focused desire.... I think all of us who are interested in the arts made a mistake in not latching onto it and stretching it out more." But early this year, while publicly advocating unrestricted reauthorization, Pell offered Helms a deal that would have postponed the fight even longer—until after the November elections—extending authorization for another year with the current obscenity restriction. Pell, who will be seventy-two this fall, is facing a tough challenge from Republican congresswoman Claudine Schneider, and one staffer acknowledged that "it is awkward for him to have to do both, to run for reelection and to reauthorize the endowment under these circumstances, all at the same time." Helms turned down the deal, perhaps sensing an edge.

He was right. The bill that Pell put forward this July conceded the ground that Helms won last year. By that time, the White House, which had firmly supported unrestricted reauthorization, had backed down, too; so, despite opposition from a Democratic majority in Congress and that of a president from his own party, Helms had triumphed before this summer's battle even started.

This jerk over here's talking about A censorship of the arts, and you're never going to go to an art gallery? And I'm worrying about your kids' education? And I'm worried about health-care costs? And I'm worried about drugs? And I'm worried about our environment?... The coastal wetlands in this state are being raped, and rivers are being declared dead, and Jesse Helms is supporting the clearcutting of forests in this state—our wilderness areas—and he's supporting that? And this guy's telling you that the issue in this campaign is whether we're going to bash gays and lesbians?"

Harvey Gantt is having an imaginary conversation with the voters of North Carolina, convincing them that the politics of Jesse Helms have at last been left behind by the times. Sitting in a nearly empty office in his Spartan campaign headquarters in Charlotte, Gantt goes on, laying it out as he plans to lay it out for voters this fall: North Carolina is last in S.A.T. scores, next to last in industrial wages, and has the highest infant-mortality rates. Jesse Helms fiddles with arts and AIDS while his home state burns, and North Carolinians aren't going to take it anymore.

It is the eternal hope of Democrats, and has been in every campaign against Helms since 1972. And in every campaign since 1972, Jesse Helms—finding an issue, coming from behind, beating the odds— has found a way to win. But this is a different kind of campaign: there are signs, including two major polls taken in the late spring, that seem to show a real Helms vulnerability.

In his 1972 and 1984 campaign victories, Helms was helped by the coattails of two Republican presidents, Nixon and Reagan, who won landslides in North Carolina; he'll have no such help this year. The Republican lock on the "no new taxes" theme, electoral magic, was broken the moment George Bush changed his position in June. "Helms is an incredibly wounded animal," says Saul Shorr, a Democratic consultant who designed the campaign of Mike Easley, one of the candidates that Gantt defeated in the primary. And Gantt, the former mayor of Charlotte, is a different kind of candidate.

He is the first black ever nominated by the Democratic Party to run for the Senate in any state, and his uphill primary battle against Easley and two other white candidates showed steel. Emphasizing broad coalition-building, he won without the backing of labor and despite the widespread conviction that a black candidate had no chance.

As soon as it became clear that Gantt would be his opponent this fall, Helms says he notified his staffs in Washington and Raleigh that "some heads will be cracked if anything is done that even appears to be racist." The fact that Helms had to issue such an edict says something about his reputation, and campaigns of the past.

Rob Christensen and Chuck Babington, two experienced Helms watchers for the Raleigh News and Observer, have often reported on Helms's subtle use of codes to play upon racial prejudice in his campaigns and fund-raising appeals. For example, he sent out fliers showing his 1984 opponent, Jim Hunt, a popular moderate Democratic governor, with headlines reporting a drive to increase minority registration. A recent Helms mailing said of Gantt, "Jesse Jackson's wish came true .... Harvey Gantt, his ally, is running against Jesse Helms. And Doug Wilder, who was just elected Virginia's governor, is signed on to help them."

Carter Wrenn, Helms's fund-raiser, says the accusations of racial motivations are "ridiculous."

"In describing Gantt's campaign, it is a fact that the people who helped in the Wilder campaign [Wilder's pollster] encouraged Gantt to run and are helping to run the Gantt campaign. How do you tell that story and avoid the fact that some of those people happen to be black? It's not possible."

Of course, the use of coded campaign messages would not seem a necessary tactic in this campaign, in which Gantt's race will presumably be discerned by the voters without Helms's assistance. Helms might be on firm ground in portraying Gantt as being more liberal than the Carolina mainstream, but, as Shorr says,

"if the question Helms forces them to decide is 'Are they racist?' there'll be some backlash and Harvey will get votes because of that."

(Gantt is taking no chances on the race issue, either; he has discouraged his boyhood chum Jesse Jackson from coming to North Carolina to campaign. "Jesse Jackson is a drag on a part of the constituency we're interested in," Gantt says bluntly.)

Another heated Helms issue, abortion, may also prove tricky. Gantt's campaign is counting on a big gender-gap vote, and Helms, of course, won't budge. "The other crowd said they're gonna beat me on this one, and maybe they will," Helms tells his supporters in Goldsboro. "But let me tell you, I meant it when I supported without fail and without hesitation the right of unborn children to be bom so that they can have a chance, a chance to live and to love and be loved."

Helms's success has always depended partly on his ability to jolt voters with socalled hot-button issues. With many of his standby weapons blunted or obsolete, the N.E.A. may be the best issue left in his political arsenal.

I want to be in that nummmmberrrr, when the saints go marchin' in!"

Jesse Helms leans against a desk in his Washington office, singing along merrily (and quite badly) with the toy bugler Mrs. Helms gave him for Christmas. It is the morning after Harvey Gantt's primary victory, and Helms is declaring his peaceful intentions toward Gantt, and toward the world in general. "He is a nice man," Helms says of his Democratic opponent, "and I wish him well." The campaign, he adds, will focus on issues, rather than making negative attacks, and certainly not on race. "It's all up to the Lord and the people of North Carolina—we'll just do the best we can and not worry about it."

It is a lovely performance, and fraudulent on its face. Helms's very surroundings reveal a nature given more to combat than to conciliation; the walls of his Senate office are filled with caricatures of him, some quite vicious, proudly displayed in the manner of a man who enjoys hostile engagement.

That afternoon, Helms proceeds to the Senate floor and ambushes a piece of legislation by his arch-enemy, Ted Kennedy. It is a bill of rights for handicapped Americans, but Helms attaches to it a recommendation banning people with AIDS from certain restaurant jobs. Kennedy squawks, protesting that Helms's measure frustrates the spirit of his bill, even invoking the name of Ryan White, the late AIDS poster boy, who, Kennedy says, would be barred by Helms from a summer job at Burger King. To no avail. Before introducing his amendment, Helms takes a little poll in the Senate cloakroom: "If your favorite restaurant in Alexandria were known to have a chef who has AIDS or any other communicable disease,'' Helms asks, "would you take your family there to have a meal?" The answer is a unanimous "no," testament to that potent Helms alchemy of logic, emotion, and fear. It works in the cloakroom, and it works in the full Senate; to the surprise of many—including Helms's own staff (but not, clearly, Helms himself)—his amendment passes, leaving to Kennedy and his allies the chore of undoing the emotion-charged provision in a SenateHouse conference.

In the Helms view of things, any day that includes a victory over Ted Kennedy is a good day, and if it brings a shot at "the sodomites" too, then it is fine indeed. But this is a bonus day: without breaking a sweat, Helms also gets to knock down the N.E.A.

Returning to his office, he reluctantly meets with a few members of the press (a group that the former newspaperman so deeply loathes that he refuses to give his daily schedule to his press secretary, Eric Lundgren, for fear that Lundgren will let reporters know where Helms will be). The conversation turns to the N.E.A. The White House has rather sheepishly floated a compromise proposal: might Congress accept a one-year reauthorization, delaying the bloody battle until after the November elections? Friends of the troubled arts agency still hoped, naively, that Helms, who had been relatively silent on the N.E.A. for a few weeks, might be amenable to compromise and negotiation. "Will you," Helms is asked, "allow a one-year cooling-off period?" And in an instant, Helms turns the White House proposal to dust.

"I think we oughta confront the issue," he says. "Should pornography and obscenity be funded by the taxpayer?

"I say no."

Those three words are the lyrics to the Jesse Helms anthem, uttered with the assurance of a man who believes he can get a congressional chorus to sing along. It's just a matter of knowing which hot buttons to push. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now