Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDEAD RECKONING

The chilling saga of Henry Lee Lucas is part Deliverance, part In Cold Blood. A drifter who was convicted of murdering his mother, Lucas thrilled the tabloids and the Texas Rangers when he claimed to have butchered six hundred more people. Then he abruptly recanted his confessions. If Lucas is innocent, what fueled his perverse desperado tale, and why won't the Rangers admit they have the wrong man? RON ROSENBAUM reports from death row

RON ROSENBAUM

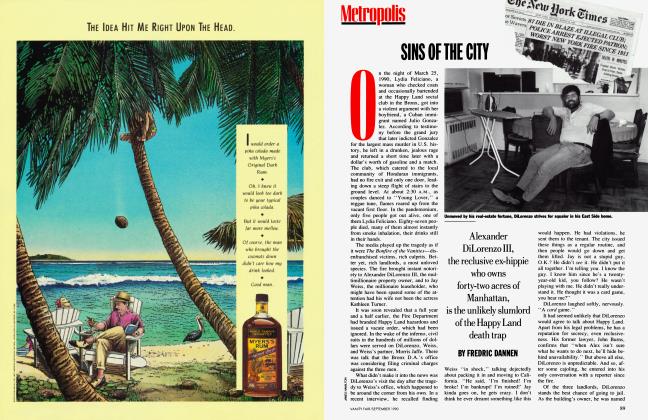

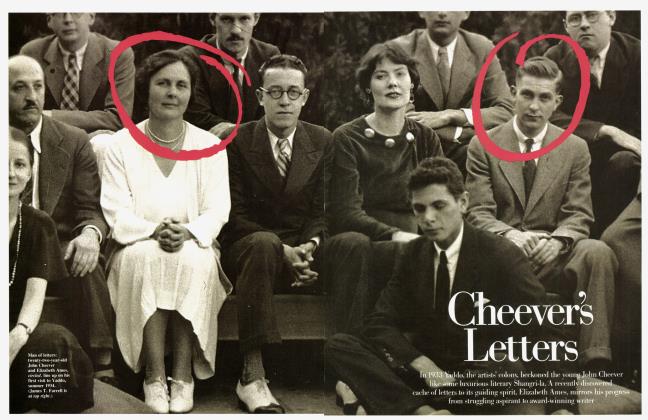

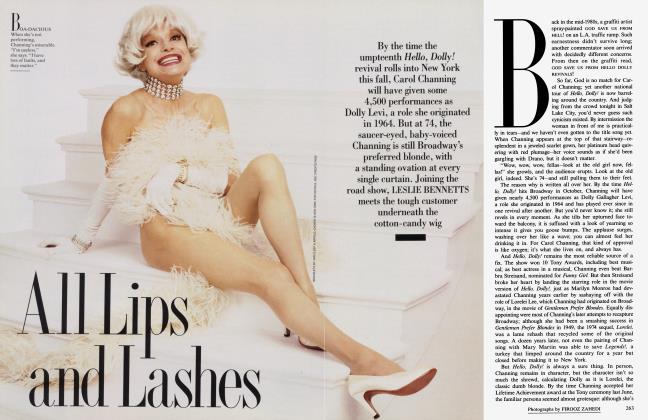

A serial-killer celebrity Lucas jetted around the country like a rock star on tour.

Face-to-face with Henry Lee Lucas—the man who is either the worst killer or the best liar in American history—one naturally looks into his eyes for a clue.

I watched Lucas's eyes as he told me his version of the whole strange and bizarre saga. How he went about creating a monstrous myth about himself—the myth of Henry Lee Lucas, the Grim Reaper of Road Kills, an insatiable serial killer ceaselessly scouring the interstates for drifters and strays, enticing them into his car, then leaving their slaughtered, violated bodies behind in ditches beneath the exit ramps.

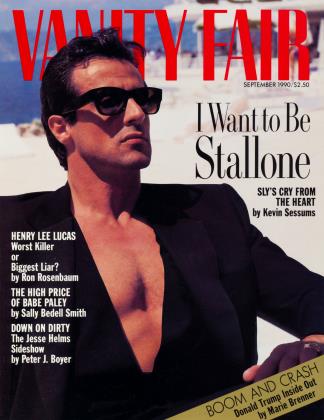

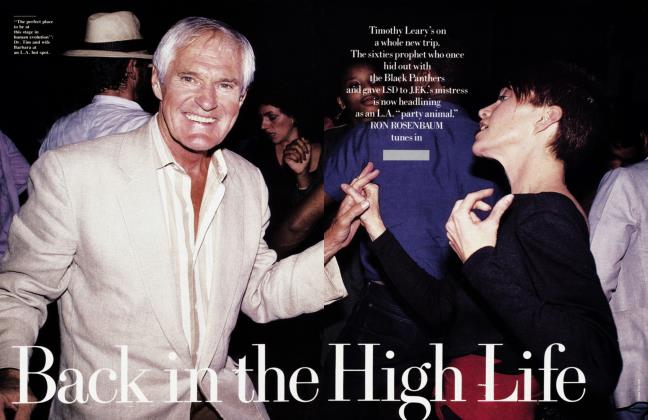

It's the myth you see embodied with utter credulity in the newly released docudrama Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. It's the myth that earned him international serial-killer celebrity in the mid-eighties, as he jetted around the country like a rock star on tour, descending on towns with his entourage of Texas Rangers, "singing" for his supper: solving long-unsolved murder cases for local detectives by confessing to the killings himself.

He became the perfect incarnation of a new kind of specter haunting America in the eighties—the serial killer who struck with motiveless malignancy and chilling casualness, who didn't need to feel the apocalyptic delusions of a Manson to prompt him to kill, who felt, in fact, next to nothing at all. "Killing someone is just like walking outdoors," Henry Lee Lucas liked to say. And unlike Ted Bundy, who denied all till the very end, Henry was happy to confess, happy to chew the fat with the shrinks who flocked to him to confirm their theories about serial-killer psychology.

And then, suddenly, Lucas tried to kill off the myth, recant, retract it. It's been investigated, "exposed," and some have believed his retraction. But not enough: Lucas still has a Texas death sentence and the equivalent of nine life sentences for murder stacked on top of that.

It's a myth that will not die—indeed, one Lucas may die for. Later this year, the long-smoldering Lucas controversy is likely to flare up again when Florida authorities put him on trial and seek to stick him with three more death sentences, for killings they say he confessed to, he says he didn't commit.

Here on death row in Huntsville, Texas, condemned men are separated from visitors by wire-reinforced glass. But even through the glass it doesn't take long to see there is something unusual about Henry Lee Lucas's eyes, something that would have made his gaze an asset to either a killer or a liar—a mask to conceal his true intentions. It's got something to do with the fact that one of Lucas's eyes is glass. But it's not just the glass eye that makes Lucas's gaze so unfathomable. It's that the other one, the real one, is so blank and apparently emotionless it's often disconcertingly difficult to distinguish the real from the false orb, much less the real from the false sentiment behind them.

It makes you realize how much the ability to read emotion in someone's gaze depends on the effect created by two eyes in tandem; to look into Lucas's half-glazed gaze is to experience the visual equivalent of the famous "sound of one hand clapping." There's no there there.

Indeed, the whole strange Lucas saga is one in which reality and myth, truth and falsehood, have continued to abide side by side—like Lucas's eyes, challenging those who would seek to distinguish them definitively.

I'd set out to see Lucas, half believing the myth. The half that believed had been influenced by a conversation about necrophilia with a true believer in the Lucas myth. This Dallas-based forensic psychiatrist, who'd examined Lucas in the past, cited him as a prime example of the propensity of serial killers to sexually assault the bodies of their murder victims.

But wait, I'd said, hadn't I read something about Lucas having recanted his confessions?

Yes, he replied, Henry had recanted, but he still believed Lucas had killed "around sixty," if not the six hundred he'd claimed at one point.

I wrote to Lucas down on death row in Huntsville, scheduled an interview with him. But after reading over the clipping file, I decided that a detour to El Paso would be necessary first. The file indicated that doubts about the Lucas serial-killer myth were far more serious than I'd gathered from the psychiatrist. It wasn't merely that Lucas himself had recanted his confessions, but that they'd been investigated by the Texas attorney general's office, which had called the Lucas confessions "a hoax" and cast doubt on all but two of the more than six hundred murders Henry had once claimed responsibility for.

The file indicated that a kind of range war had broken out between rival branches of Texas law enforcement, with the Texas Rangers—who'd recouped some of their former glory by managing the Lucas confessions— sticking to their guns, blasting the attorney general's hoax claim, insisting Lucas was the real thing, thus leaving the truth in official limbo.

The file pointed to a mid-1986 El Paso

court hearing as a kind of High Noon showdown between believers and debunkers of the Lucas myth.

Down in El Paso, I found a gold mine of astonishing and scandalous testimony about the Lucas confessions. At issue at the hearing was the legitimacy of just a single Lucas SS-J confession—to the ax murder of an ■"'"'"T **«*

elderly El Paso woman. But Lucas's intrepid El Paso attorney, Rod Ponton, B had taken on the Texas Rangers and pul the entire confession process, the entire Lucas myth, on trial. I spent a week immersed in the six-thousand-page hearing transcript and then, in Rod Ponton's basement storage room, I came across a major find: the confession tapes. Hour after hour of Lucas on videotape confessing to murder after murder to team after team of homicide detectives from all over the country.

By the time I settled in to watch the confession tapes, I'd already become far more skeptical. It wasn't merely the El Paso hearing record—which was devastating in itself—but also a long conversation over dinner with the judge who had presided over the hearing,

Brunson Moore. A fiery jurist who was still fuming over what he had seen exposed in his courtroom, Moore was outraged that the Texas Rangers had refused to admit they were wrong, refused to go back to police departments all over the country and tell them that Lucas was a fake, that the real killers in all those murders Lucas had confessed to were still at large.

"You're talking about hundreds of murderers let off the hook," Judge Moore told me, "and what have they done? Nothing!"

Watching the confession tapes, I found myself fascinated with the mechanics of the Lucas con game, with the elaborately choreographed dance of deceit and self-deception going on between Lucas and the detectives he was psyching out. Here was Henry Lee Lucas, one of the Great Pretenders of the eighties, one of the classic American con men of all time in fact, doing his act before my eyes.

There was one moment in particular of all I'd seen and read that lingered in my mind. The "barbecue sauce" line. It was a joke of sorts, but one that let the mask slip and seemed to reveal what was really going on behind Lucas's eyes: a black-humored cynicism, chilling in its contempt for the credulous, one that seemed to find its deepest psychic satisfaction in seeing just how much shit he could get them to swallow.

The moment came in the midst of one of Lucas's discourses on the Hands of Death. This was the purported Satanist ritual-murder cult into which he claimed he'd been recruited by his serial-killer partner in crime, Ottis Toole. Lucas was explaining how, at the behest of the Devil-worshiping Hands of Death, he would often crucify his victims—after which Ottis Toole would often barbecue and eat them.

He himself, Lucas said, never joined Ottis in these unholy feasts.

Why not? he was asked.

"I don't like barbecue sauce," he said.

The Lucas I came face-to-face with at Huntsville was strikingly different from the Lucas I'd seen on the confession videos. Back then, five years ago, at the height of his serialkiller celebrity, Lucas was a leaner, meaner, more threatening-looking figure. His dark wavy hair and that inscrutable stare made him look like one of those gaunt, dangerous characters John Garfield played in forties films noirs. These days Henry's pudgier; he's kept the weight he put on during the confession spree, when he was rewarded with a strawberry milk shake for each new murder he agreed to confess to. Now fifty-four and graying, Henry looks less like John Garfield than, say, Carroll O'Connor—certainly less like a killer than he once did.

But in fact he is a killer. Even those who believe his confessions were all lies concede he killed one person, perhaps three. And even Henry willingly admits he's responsible for one death. He's already done time for it. It was the murder of his mother, and one of the first things I asked him was how he came to kill her.

"I was brought up like a dog," Lucas told me that morning we first met on death row. "No human being should have to be put through what I was." And the facts (the following account has been independently corroborated except where noted) are fairly appalling.

Henry's stepfather was an alcoholic double amputee who lost his legs in a railroad accident. "My mother was a prostitute who brought home men, and I was made to watch sex," he said.

They lived in a fairly primitive logcabin-like dwelling in an isolated backwoods county in western Virginia, the kind of hillbilly milieu that produced the predators of Deliverance. His mother dressed him up in girls' clothes, beat him when he rebelled against it, sent him out to sell moonshine. When he was seven years old an injury to his left eye caused him to lose the orb.

Henry left home early, and for a while it seemed he'd escaped the baleful effects of his upbringing. He met a girl named Stella. "She was a factory girl, a hard worker, you know. And I fell in love with her and wanted to get married."

He visited his mother, who now lived in Michigan, to tell her about Stella. They went out drinking. His mother indicated she didn't approve of the marriage.

"I went home with her and I was laying there in bed and all at once I felt something hit me upside the head. She took a broom handle and, boy, she wore it out on my head. And I jumped up, you know, I swing and I don't know whether I had something in my hand or not, but they say I did. And she was hit on the neck or chin or somewhere and I killed her."

In 1960, Lucas was convicted of second-degree murder in the stabbing death of his mother. He still disclaims any memory of the use of a knife.

"At the trial," he said, "I told them I did hit her, I says, 'I guess you could say I'm guilty.' Well, they charged me with second-degree murder, and give me twenty to forty."

On the morning of August 22, 1975, Michigan authorities released Henry Lee Lucas from state prison at Jackson. It is at this point that the Lucas story bifurcates into two radically different, contendnarratives. If you believe the narrative compiled by the now defunct Henry Lee Lucas Homicide Task Force based on Lucas's confessions—let's call it "Version A: Henry, Serial Killer"—the moment he got out of prison, Lucas met the man who would become his accomplice in murder, Ottis Toole, and the two of them took off like a shot, driving thirty hours south to Lubbock, Texas, where they broke into the home of nineteenyear-old newlywed Deborah Sue Williamson and stabbed her to death, thereby inaugurating their nonstop marathon of murders. It would continue for eight years and claim 160 or 360 or 600 more victims (depending on when you asked).

"My mother was a prostitute who brought home men, and I was made to watch sex."

There are some problems with Version A, not the least of which is that, by most accounts, Lucas and Toole didn't know each other in 1975, didn't meet until 1979. But let's set that aside for a moment and proceed to the alternative scenario, which might be called "Version B: Henry, Hapless Drifter and Bum.'' Version B does have the advantage of being corroborated by work records and the recollections of neighbors, relatives, and co-workers.

In Version B, Lucas spent the night he was supposedly murdering Deborah Sue in Lubbock at his half-sister's home in Maryland, beginning to attempt to adjust to postprison life. It would not be easy. Lucas was a thirty-nine-year-old ex-con with a glass eye and an adjustment problem, and even if he was not a serial killer, he was certainly no saint.

"I didn't have the outlook that normal people have," Lucas says. "I'd call myself abnormal because of where I'd been and what I'd been through. It took me a long time after I got out of prison to adjust, you know, to society."

But, he contends, "eventually I adjusted pretty good." For a while, at least. He moved to Maryland, where his half-sister lived. Through her he met a woman named Betty who took a liking to him, and they got married. "I married him for companionship," she'd later say. And Henry Lee Lucas did seem to have a talent for companionship. He was a drifter, not much better than a bum, but people always seemed to be taking him in, offering a place to stay, work, friendship.

But the stretches of settling down, making friends, never lasted long for Lucas. Something always seemed to bring them to an end; there would be misunderstandings, "false accusa-

tions," he says—that's what happened to end his year and a half of married life in Maryland.

"I tried to live the right type of life. I seen that the kids [his wife's three daughters by a previous marriage] were provided for. I got them a home, where they didn't have one before. And I worked as a roofer, paid the rent, did everything possible. And the more I'd done—" He breaks off and then resumes bitterly, "It didn't mean nothing."

"What do you mean by that?" I ask him.

"My wife accused me of having sex with her kids, and when she accused me of that I said, 'No more,' I couldn't take no more. That tore me apart. I just left and never came back."

He took refuge with his half-sister, but once again, he says, a "false accusation" of molestation drove him out. He hit the road—and the road hit back, hard. By February 1979, Lucas was down-and-out, seeking succor at a relief mission in Jacksonville, Florida. It was there, according to the Texas attorney general's investigation, that he first met Ottis Toole, a six-foot-tall occasional transvestite and arsonist with a build like a linebacker's and a voice like Truman Capote's.

"Ottis looked to cruise the mission, pick up men, have sex with them, and then beat them up," Lucas recalls. Though Henry indicated a lack of enthusiasm for sharing this experience, Toole took a liking to him anyway, invited him home to meet his mother, offered Lucas a place to stay, got him a job with the roofing contractors he worked for. According to Lucas, he and Ottis were running buddies, pals; they never had a sexual relationship. (Toole indicated otherwise to me in a subsequent interview.) He stayed in the Toole household, he says, because it became the family he'd never had. Indeed, before long, two children arrived: Toole's niece and nephew Becky and Frank Powell, twelve and nine. Both of them would have fateful roles to play later on in the Lucas saga.

But it didn't last, this idyllic period. Nothing good in Henry Lee Lucas's life did. Toole's mother died and a squabble between Toole and his brothei resulted in Henry and Ottis's being kicked out.

"I got so sick of looking at those pictures... naked women, people cut up in pieces."

Soon they banded together with Frank and Becky, along with a Chihuahua, a cat, and some parakeets, in Henry's ancient, broken-down Oldsmobile. They hit the highway, heading west to join the dispossessed of the earth.

"That began my travels,'' Lucas says of the period when he began roaming the interstates, looking, he says, for some place to call home.

By Lucas's account it was a pathetic odyssey. They were so poor he had to go from town to town selling his blood to blood banks in order to pay for the gas to keep going. When the car broke down, they'd hitchhike, hop a sooty freight car, split up, double back to Florida, and take off again, generally getting nowhere and accomplishing nothing. Except perhaps one hundred murders: according to the Henry Lee Lucas Homicide Task Force (and Lucas's original confessions), this was when Lucas and Toole were at the height of their serial-killer mayhem—sometimes killing two or three people a week, picking them up on the highway or brazenly breaking into their homes, robbing them before raping and murdering them. All of this with two kids in tow.

According to Lucas, the only deaths that occurred in these travels were those of the Chihuahua and the cat, who didn't survive the heat. (He sold the parakeets "to a man under a bridge'' for gas money.) As he points out, and as investigators later verified, blood-bank records in places like Houston and New Orleans verify that Lucas had been selling pints of blood for seven to ten dollars every week or so. "If we were doing all those robberies and burglaries, why would I be selling my blood for a few bucks?" he asks.

Selling blood or spilling blood, this period of Henry's travels finally came to an end in May 1982, when he and Becky—who'd split off from Ottis and Frank—were out hitching by a truck stop near Wichita Falls, Texas, and caught a ride with the Reverend Ruben Moore, a roofer and lay preacher who offered them shelter at his nearby religious refuge, the House of Prayer. Developments there would soon bring Henry Lee Lucas to the attention of the world.

The House of Prayer was a spooky place, something out of Flannery O'Connor: an abandoned chicken ranch consisting mainly of long, low chickencoop sheds that, had been subdivided into residences for the drifters and lost souls who found shelter there.

Henry and Becky moved into one of the abandoned chicken coops, Henry using his roofer's skills to turn it into a cozy apartment for the two of them.

Once again, for a while at least, Henry Lee Lucas had found a place of refuge. Henry and Becky became part of the community of wayward souls, even attended the Sunday-night prayer meetings, where the sound of speaking in tongues was heard within walls once accustomed to the clucking of hens.

But before long, Becky, who by now was fifteen, began getting restless in this bleak prairie setting. She talked about going back to Florida. Henry thought it was a mistake. They quarreled. When Becky announced she was going to hitchhike to Jacksonville by herself, Henry set off, determined, he says, to hitch with her to Florida, see that she got there safely.

Henry now says he last saw Becky at a truck stop in Alvord, Texas. He'd gone into the truck-stop cafe to see if any drivers were heading to Florida. When he turned and looked out the window, he says, he saw Becky getting into a Red Arrow truck.

"I run out of the truck stop and started back down the hill a-hollering and they slammed the door and took off. And here was my bag sitting by the road, you know. They took everything except my bag. Left my bag sitting on the road. I didn't know she was gonna run off from me."

Henry returned to the House of Prayer, and Becky hasn't been heard from since. Some, even those who don't believe Lucas is a serial killer, believe this is one murder he did commit. The summary of a lie-detector exam administered on behalf of the Texas attorney general's office in 1985 (after Lucas recanted his serial-killer confessions) indicated that Lucas "caused the death of not more than three people"—and that he "repeatedly indicated deception" when he denied involvement in the murder of Becky Powell.

He also "repeatedly indicated deception" in denying involvement in one other murder, that of a woman who lived not far from the House of Prayer, an elderly widow named Kate Rich. It was, in fact, suspicion of Lucas's involvement in the death/disappearance of Kate Rich (her house had burned down, her body had not been found, Lucas says he visited her on the day of her disappearance) that brought Henry into the purview of the local sheriff, W. F. "Hound Dog" Conway.

And it was the aptly named Hound Dog's zeal in pursuit, Lucas says, that gave rise to his whole false-confession spree. Hound Dog first pounced on October 18,

1982, arresting Lucas on suspicion of the murder of Kate Rich, putting him in the Montague County jail, and holding him incommunicado,

Lucas says, for two weeks. He was released without being charged, but, Lucas says, Hound Dog kept bird-dogging him, "harassed" him for seven months, until finally arresting him on a gun-possession charge.

This time, Lucas says, Hound Dog put the screws to him, locked him naked in an "ice-cold cell" furnished with only a bare steel bedframe. It was the cold that pushed him over the edge, he says; even though it was spring outside, a big industrial-strength air-conditioning unit in the cell blasted him with freezing air twenty-four hours a day, giving him shivering fits. He claims he was told it would go on like that, without access to counsel, without a scrap of clothing or a blanket, until he confessed. (In sworn testimony at the El Paso hearing, Sheriff Conway denied any impropriety in his treatment of Lucas.)

Everything that happened next, the whole twisted saga of the serial-killer confession spree, with all its bizarre and disturbing consequences, was the product of the desperation engendered, Lucas says, by that cold-cell "torture."

That's how he explains why he started confessing—"I did what I had to do to get out of that cell." But two confessions would have been enough for that; the hundreds that followed, he says, were payback. Paying lawmen back: for a lifetime of "false accusations," he'd give them a lifetime of false confessions. The lifelong victim of authority would now victimize the authorities, put them to shame.

That's Lucas's explanation, based on his insistence now that he didn't kill Becky Powell or Kate Rich. But, in fact, if we believe he did kill Becky and Kate, the fake-confession spree makes

more sense: knowing he was going to be nailed for two, he'd have much less to lose confessing to hundreds. And he might have something to gain. The false confessions, once exposed, might throw a cloud of doubt over the two murders he did commit.

Whatever the complexities of his motives, his initial efforts to portray himself as a serial killer ran into trouble almost immediately. Indeed, the story of Henry Lee Lucas's serial-killer confession spree is really the story of Lucas's evolution from a crude and unconvincing confessor whose act almost folded at the start to a brilliantly inventive con artist, the Olivier of the false confession, who learned how to analyze and play to the psyches of the lawmen he gulled into complicity in his charade.

Here's how it began. On the night of June 17, 1983, Lucas called out to his jailer and announced that he had something to say. He proceeded to confess to

the murders of Becky Powell and Kate Rich. He threw in some horrifying details, claiming the reason Kate Rich's body had never been found was that he'd chopped it up and burned it down to ash in the wood-burning stove at the House of Prayer.

But he didn't stop there. He told local Texas Ranger Phil Ryan, who'd been following the case (these days the Rangers function as a kind of elite band of super-state troopers, often stationed in small counties to lend criminal-investigation expertise to local sheriffs), that he'd killed at least a hundred more. Ranger Ryan asked Lucas to write down

the details of all those murders. The document he produced almost ended the whole business then and there. It was a three-page, primitively scrawled list of seventy-seven people he'd supposedly killed. There were childish, cartoonlike "sketches" of the victims' faces, accompanied by disjointed descriptions:

Junction, Plainview, I-10. Date, 1979. Death, cut head off, knife. Started strangling, stab back, white female, 20, medium, red hair, lots of makeup, five-two, 135, pretty. Picked up, put head in sack, dropped in Arizona, body.

The key to all that happened later, Lucas says, was that the word went out before any proof came back. "The sheriff went in front of the press immediately," he recalls, "and said that I'd killed hundreds."

The Henry Lee Lucas traveling circus had begun in earnest.

"They were (Continued on page 274) (Continued from page 197) flying in from all over the country," he says. "Helicopters, everything else flying into that tiny town. Lawmen, news media, writers. .

Perhaps if word hadn't gotten out so fast, if lawmen hadn't found themselves committed so soon to the proposition that they had a serial killer confessing in their custody, they might not have been so committed to the proposition when the problems began to develop.

Which they did very early on. There were problems with that first list of seventy-seven victims. As the Texas attorney general's review of the case states, law-enforcement officers began to investigate and "recognized immediately that Lucas's description of the abduction/murder of a juvenile female had never taken place." (Italics are mine.) Several other places where he'd claimed to have buried bodies, including an abandoned chromium mine in Pennsylvania called the Bottomless Pit, were thoroughly searched and turned up no bodies. Indeed, none of those seventyseven claimed kills was ever linked to a real body.

When you think about it, it's not that easy to convince the world you're the greatest serial killer in American history just on your own say-so. The confession spree couldn't have continued with Lucas just making up murders and sending people looking for bodies that weren't there. He needed a score. The key to his first success, the key to all the successes that followed, is evident in Lucas's description

of that first big score: reversing the information flow.

That first score, Henry says, involved a murder in Conroe, Texas, north of Houston.

"Sheriff Corley from Conroe, he sent his deputies up to Montague and they showed me all the pictures of the murder victim right off."

Henry said, sure, he remembered her— that was one of his kills.

"Then they said, 'We want to take you down there and let you point out the crime scene to us.' And they drove down there and drove me around everywhere and I couldn't find it."

"You couldn't find it?"

"Until they pointed it out to me."

"Let's get this straight. They stopped by the crime scene and said, 'Here we are, Henry...' "

"Yes: 'Does this look familiar?' "

"You learned to pick up on cues?"

"On what they wanted."

(Sheriff Joe Corley insists that—while he was suspicious of some of the cases Henry tried to take credit for in his county—the two that he did clear with Lucas were genuine. He denies that he or his men gave Lucas any details about the crimes in advance.)

Reversing the flow: instead of making up bodies, lawmen would bring bodies, pictures of them, to Lucas. Sometimes they'd play a kind of reverse Twenty Questions in which he would cannily use trial and error to "remember" a description of his victim ("Yeah, I had one up

near Lake Michigan—she was a blonde girl about twenty. . . . Oh, she wasn't blonde? Could've been light-brown, brownish hair. I got so many I get 'em confused"). When he finally guessed right, the lawmen and Lucas would pile into a car, and again by means of trial and error, mostly error, and by picking up often unsubtle clues, he'd "find" the crime scene. Afterward, detectives would announce that Lucas's confession had been verified because he "supplied officers with details only the killer could have known, and led them right to the crime scene."

Or as the Texas attorney general's report summarized, "Lucas would use information provided him during questioning by law enforcement personnel to fabricate confessions."

The next key turning point in Lucas's rise to world-class serial-killer status was the "Orange Socks" confession. It was the Orange Socks confession that got him the death penalty in Texas, that left him truly with nothing to lose. And the Orange Socks confession brought him into the jurisdiction of the lawman who was to become Henry's father confessor, his father figure, the man in whose custody he would become an industrial-strength dynamo of a confession machine: Sheriff Jim Boutwell.

Orange Socks was the name given to a young woman whose unidentified body was found in a ditch off a lonely stretch of Interstate 35 in Williamson County, Texas. Her body was nude except for a pair of bright, fuzzy orange socks. In a way, Orange Socks was typical of the kind of victim Henry Lee Lucas would most successfully claim as his. Probably a hitchhiker (no local people recognized her). Probably an outcast of some kind (nationwide circulation of her picture produced no grieving family to claim her). A fouryear-old unsolved homicide with no suspects, no leads, until Sheriff Jim Boutwell visited Lucas in jail and asked him if Orange Socks was one of "his."

Boutwell brought Lucas to his jail in Georgetown, Texas, a small town half an hour north of Austin, after the Orange Socks confession and kept him there. Kept him there and got a special appropriation from the Texas Department of Public Safety, with the governor's blessing, to establish a Henry Lee Lucas Homicide Task Force, to be jointly administered by Boutwell and the Texas Rangers.

"Things really skyrocketed in Georgetown," Lucas says. "I went from one a day or twice a day to seven days a week, probably five or six officers a day came in there."

Lucas certainly seemed to be driven to increase his productivity under the influence of the sheriff. As the attorney general's report notes, Lucas had started with those seventy-seven claimed kills, but "while talking to Sheriff Boutwell on June 22, 1983, he increased the tally to 156. His final estimate [under Boutwell's supervision] was over 600." (Boutwell, a courtly former Ranger and legendary Texas lawman, insisted to me that the 160 or so Lucas confessions actually cleared under his supervision were all properly handled, solid cases.)

The Texas Rangers were the outside men for the task force, the link to state and national law enforcement. They booked detectives who signed up two and three months in advance for appointments with Lucas; they organized "Lucas seminars" to share their serial-killer expertise under the prestigious auspices of the Regional Organized Crime Information Center.

And Lucas had good reason to keep increasing his numbers for the task force. The more cases he confessed to, the more rewards of milk shakes and jail perks he received. He was living high off the hog in Georgetown, better in his carpeted jail cell, he says, than he'd ever lived "outside" in his entire life. He'd been a drifter and a bum living in a chicken coop; now he was an international celebrity, entertaining Japanese camera crews, making book and movie deals for his life story. And there were deep psychological satisfactions: the ex-con lowlife who'd been pushed around by lawmen all his life was now manipulating the hell out of lawmen, making them dance to his tune, and laughing behind their backs. Toward the end he was almost testing them to see how much they'd swallow, how outlandish the stories could get, claiming to have bumped off Jimmy Hoffa for the Mob and to have flown the poison to Jonestown in Guyana.

Like the con-man hero of Gogol's "Dead Souls," who goes around buying title to dead serfs in order to inflate the value of his estate and social position, Henry Lee Lucas rose by taking title to the dead. The ever higher numbers ensured his stay in the Georgetown jail, where he'd taken up oil painting when he wasn't watching premium cable channels like HBO and Playboy on his personal color set, or ordering in his favorite take-out foods from the Sonic drive-in and other local eateries he preferred to the jail kitchen.

The higher the numbers, the longer he'd enjoy his perks. And when he stopped confessing? As Texas Ranger Bob Prince, co-chief of the task force, put it in an adulatory profile in Law Enforcement News, "When [Lucas] gets to the point where he has no more information or he doesn't want to talk with us anymore, death row is waiting for him down there at the penitentiary."

Or, as Lucas put it to me, Prince "said my goose would be cooked."

In fairness to the lawmen far and wide who fell for his confessions—despite the dearth of physical evidence linking him to the crimes (not a single fingerprint, for instance)—there was one confessional ploy of Lucas's that succeeded spectacularly well. He came up with an eyewitness to attest to his killings. Not merely an eyewitness, but an accomplice. He came up with Ottis Toole. He and Toole were a killing team, he said, from the beginning. Toole had recruited him into the Hands of Death Devil-worshiping cult. Toole was, if anything, even more bloodthirsty than he (the barbecues).

The astonishing thing was that, as ludicrous as these stories sounded, Toole cheerfully confirmed them all.

Lucas says it "came as a surprise" to him when he heard that Toole was backing him up on these tales.

"I didn't expect him to take the cases," Lucas says.

But fate, which had separated the two men back in 1982, had landed them in similar desperate situations in late 1983, when Lucas started including Toole in his confessions. Toole by then was also in jail, facing the death penalty in Florida for an arson-murder rap (he had been convicted of burning down a rooming house, a fire in which an old man died). Toole, like Lucas, had little to lose. And he still had a kind of romantic devotion to Henry; in his own way the Florida firebug was still carrying a torch for Lucas. The transcript of a November 14, 1983, phone call between Lucas and Toole, shortly after they joined forces in the confession spree, reveals the dynamic of their relationship. Toole reproves Lucas for breaking his word "never to run off." Lucas says something sentimental about the two of them "being together" in the hereafter. And Toole, with only the slightest reluctance (he worries about the barbecuing tales: "Wouldn't that make me a cannibal?"), enthusiastically backs Lucas up on everything.

Later I asked Toole, who is still serving time in Florida State Prison (his death sentence reduced to life imprisonment), what he had thought when he first heard Lucas was claiming they'd killed hundreds together.

"I said, 'Well, shit, he wants to make himself a pig, goddamn, I'll help him out.' I said, 'I'll pump it all in for him.' I said, 'Fuck it, I got nothing to lose.' "

"I said [to Toole], 'Let's go for it,' " Lucas told me.

"I said, 'Fire away with hell for nothing,' " Toole recalled.

And so they did. Toole's eyewitness corroboration became a big asset in selling the legitimacy of the Lucas confessions.

Lucas's Hands of Death ploy—attributing his entire career as a serial killer to his recruitment by Toole into a Satanist ritualmurder cult, i.e., The Devil Made Me Do It—served a shrewdly calculated purpose in his serial-killer impersonation. It was part of Lucas's growing effort to portray himself as a Man of Faith on a Mission from God.

It wasn't long before Lucas was claiming to have been "saved" by his spiritual counselor and platonic sweetheart, "Sister Clemmie"—a devout religious layperson who ran a jail ministry in the Georgetown jail. Clemmie hit the religious-radiotalk-show circuit describing how she'd brought a serial killer to the Lord. Lucas would go on those shows offering pious "advice to Christian youth," from his reformed-serial-killer perspective, on how to avoid the snares of Satanism. He'd even tell his radio audience that God Himself had appeared as a bright white light in a comer of his cell and spoken to him, urging him to keep confessing all his murders, "for the sake of the families"—the families of the victims he'd slain. If he confessed everything, Lucas said God told him, He would help Lucas remember where all the bodies of his victims were, "so they could be given a proper Christian burial."

Sure, it sounds like bunk in retrospect, but Lucas was playing to a powerful emotional dynamic in the hearts of the murder victims' families—the need for some finality, some fitting closure to their suffering, the primal urge to solemnize death with certainty. The horror of the unmarked grave is an ancient theme going back to the age of The Iliad, whose final book is devoted to the struggle to obtain the return of Hector's body, give it the proper burial that in some fundamental way separates civilization from savagery.

For hundreds of families across America, Henry Lee Lucas became the great solemnizer of unsolved-murder victims' fates.

But finally doing it "for the sake of the families" became Lucas's undoing. Because finally there was one family that looked a little more closely than most at what Lucas was "doing" for them, a family that wouldn't be satisfied by the consolation of false certainty—if it meant letting the real killer off the hook.

A sudden Texas hailstorm is rattling -T"\.down on the roof over the boat dock. We're on the shore of a lake somewhere in Texas. Exactly where, I've been asked not to disclose.

Under the thin corrugated-tin shelter, Bob Lemons is telling me, "We don't want to be portrayed as the grieving family everyone should pity. Do you understand? We weren't just passively grieving, we took action. We did the kind of investigation that put the task force to shame. For a while there we were unstoppable. We stopped the whole damned thing in its tracks."

It almost seems as if the Lemonses' collision course with the Lucas task force was fated. Their nineteen-year-old newlywed daughter, Deborah Sue Williamson, was supposedly the very first of the hundreds of victims Lucas killed when he got out of prison in 1975.

And of all the families of victims afflicted by the Lucas confessions the Lemonses had perhaps the most urgent reason to want to believe that his confession to the murder of their daughter was true. Because in the aftermath of the killing, their own son had at first come under suspicion. Although he was later cleared, a Lucas confession certainly would have eradicated any lingering doubts about their son. But the Lemonses smelled something wrong about Lucas's confession from the beginning.

For one thing, the first time Lucas was shown Deborah's picture, he said he'd never seen her, never been to Lubbock in his life. But, Bob Lemons tells me, a year later, "we got a phone call from a detective in Lubbock and he told me that it had been determined, that they'd had Henry to Lubbock, that he had confessed to having murdered Debbie and the case was closed. They had charged him and he would be indicted, which he was. Joyce and I, immediately upon receiving that information, went to Lubbock to hear and see what he said."

They found out Lucas had a lot of information about Deborah's murder, but "the problem was the information he was giving them was totally wrong," Bob Lemons says. "He had the description of the house wrong. He had the murder happening inside the house instead of outside. He had the description of Deborah wrong."

Particularly unconvincing, Lemons says, was the portion of the confession tape in which Lucas is supposedly "leading" lawmen to the crime scene.

"They took him to the house and asked him three or four times, 'Now, are you sure you don't remember something about this particular place? You know, and particularly out here in back in the patio area?' And he finally caught on to the fact that this [the patio] was where he was supposed to have [killed her]."

The Lemonses went back to the Lubbock detectives. "We tried to tell them, 'This is wrong, we need to put this case back into the open file. The murderer is still loose.' And they were just furious with us."

Doubts were not welcome. But doubts were driving the Lemonses crazy. They couldn't live with the notion that a false confession let the real murderer of their daughter go free.

They decided the only way to resolve their doubts was to launch their own private investigation into Henry Lee Lucas and his travels. They set off on a journey into Lucas's past, eventually selling their house to raise cash for their investigation.

They received the help of a sympathetic state trooper in Maryland, Fran Dixon, who'd had doubts of his own about the Lucas confessions he'd looked into. "He took us to Henry's half-sister, to his relatives," Lemons recalls. "And we began talking to these people and began comparing what we had with what they had on his whereabouts, and we commenced to all of a sudden realize that when Henry was supposed to be killing somebody in Texas or California he was actually in jail in Maryland or at work in Pennsylvania or living at home with someone.

"It became obvious that this whole thing was a farce," Bob Lemons says.

Before they were through, their private investigation had produced enough documents and eyewitness accounts concerning Lucas's whereabouts to discredit scores of his murder confessions. But, once again, when they sought to bring the results of their investigation to the attention of the Lucas task force, their proffer was rejected out of hand.

By this time the Lemonses weren't alone in bringing doubts about Lucas to the attention of the task force.

There was a veteran journalist in Dallas named Hugh Aynesworth. He'd co-written a book about serial killer Ted Bundy {The Only Living Witness), and originally he'd believed Lucas was a serial killer of even greater magnitude. He planned to do a biography of Lucas. But, Aynesworth says, Lucas confided to him early on that he'd only "done three" (his mother, Becky Powell, and Kate Rich). Aynesworth then began his own investigation of the Lucas-Toole travels, which ended up discrediting dozens more confessions in a Dallas Times Herald expose.

Even Sister Clemmie, the truest of true believers in Lucas and his Mission from God, began to have her doubts when Lucas started complaining to her that the task force was asking him to "take cases" that even he found objectionable. (Clemmie has remained loyal to Lucas after the shock of his recantation, and believes he's telling the truth now.)

One case Henry resisted—at first—involved the son of a lawman in a southern state. He'd been convicted of killing a convenience-store clerk and was already serving a murder sentence when Henry's confession sprang him from jail, got him a new trial and eventually an acquittal. The prosecutor who convicted the lawman's son would later testify in the El Paso hearing to his outrage and bewilderment; the prosecutor believes a false Lucas confession helped a real killer walk free.

Then there was a young crusading D.A. in Waco, Texas, named Vic Feazell, who was troubled by the way Lucas's confession to the murder of a prostitute had blown his chance to get a genuine suspect to confess. In trying to check out that one prostitute-murder confession, Feazell turned up serious problems with about a dozen other Lucas confessions. He, too, put himself on a collision course with the Lucas task force, and touched off what was to become a bitter civil war between branches of Texas law enforcement—a war which began with a showdown over possession of Henry Lee Lucas's body. The showdown resulted from Feazell's efforts to bring Lucas before his grand jury in April 1985 to testify about his confessions. The Lucas task force was extremely unhappy about this.

Feazell sent his men down to the Lucastask-force lair at the Georgetown jail. "They went down there and pretty much intimidated the Georgetown boys into releasing him and letting us bring him back to Waco,'' he recalls.

When the task force learned that its chief asset was in the hands of the enemy, it convened an emergency late-night strategy session and decided to call in the Feds to get Lucas back.

"The next morning," Feazell recalls, "two F.B.I. agents showed up in my office around 7, 7:30, demanding to see Lucas, right before he was to testify before the grand jury."

Feazell ordered his men to hold off the agents, and called for reinforcements. He called in Attorney General Jim Mattox. "He just hit the roof. He told them [the Feds] it was obviously a conspiracy because nothing but the murder of a president gets the F.B.I. out at seven A.M."

It was a tense standoff between armed men. "They were pretty upset," Feazell recalls. But he won the tug-of-war, held onto to his controversial prisoner—although he paid dearly for that victory later on.

There followed a dramatic recantation scene. What finally brought Lucas to that moment in Waco when he disavowed the whole serial-killer charade? If you listen to Lucas now, it was the mind-numbing horror of the actual confession process.

"I got so sick of looking at those pictures—it was pathetic," he tells me in Huntsville.

"What kind of pictures do you mean?"

"Naked women, murder victims, people cut up in pieces. It was just sicken-

ing. You know, it was just sickening."

It would go on twelve hours a day, five, six, seven days a week, looking at hundreds, thousands, of mutilated corpses. "And the more I would try to get away from it, the more they wanted to show me. I told Clemmie, 'I can't take looking at these pictures.' "

At first, he says, he rebelled in a kind of covert, subversive way, deliberately "going wild" with the ever inflating magnitude of his confessions to everyone and everything. After he raised his claimedkills total to six hundred in the U.S., he casually added that he'd "done about a thousand in Canada." Began claiming he'd kidnapped more than five hundred U.S. "milk carton" children on behalf of the Hands of Death and "sold them into slavery in Mexico." Threw in Jimmy Hoffa and Jonestown.

But none of these claims seemed to prompt the task force to examine any of his more mundane murder confessions, and Lucas realized, he says now, that he'd have to expose his whole act to end it. In addition he concedes he'd begun to get the feeling the jig was up—he knew Feazell, Aynesworth, and the Lemonses had been investigating him, poking holes in his story. And so, when he walked into Vic Feazell's office prior to testifying to the grand jury, "I asked them, 'What would it be if I told you that I didn't do the crimes?' And they said, 'Well, we know you didn't,' and I said, 'If I tell you that I didn't do the crimes, now they [the task force] would kill me before I got back to Georgetown.' And they said, 'What if we can give you protection?' And I said, 'I don't think you can do it.' They said, 'We'll get the attorney general up here.' So they called me in to talk to [Attorney General Jim Mattox] and he said, 'I guarantee they won't get anyone near you.' And I said, 'Well, I'll tell the truth, then.' And I said to them, 'There's some other people that deserve to know the truth.' "

"What did you mean by that?" I ask him.

" 'The Lemonses,' I said. 'I want them told the truth.' They said, 'The Lemonses already know the truth.' "

Lucas then went before the grand jury in Waco, recanted his confessions, and exposed the techniques of his hoax.

But what Lucas and the Lemonses and D.A. Feazell and the Texas attorney general didn't realize was that merely exposing the hoax confessions wasn't enough.

"Henry thought that by just telling the truth he could undo everything he'd done," Joyce Lemons says. "It was too late for that."

By the time Lucas had recanted, the machinery of the criminal-justice system had already locked in his lies and given a number of powerful law-enforcement institutions a stake in keeping them locked in. As Joyce Lemons says, "Henry had been everybody's ticket to glory, there were all these book contracts."

As soon as Lucas recanted, the task force had to fold up its tent, and he found himself quickly packed off to death row to await execution in the Orange Socks case.

One year later, in April 1986, Texas attorney general Jim Mattox issued his "Lucas Report." In addition to casting serious doubts on all but two of the Lucas confessions (Becky Powell and Kate Rich), the Lucas Report directly took on the task force and the Texas Rangers: "Those with custody of Lucas did nothing to bring an end to his hoax. Even as evidence of the hoax mounted, they continued to insist that Lucas had murdered hundreds of persons."

But partisans of the Lucas task force weren't taking this assault on their efforts lying down. According to a sworn affidavit from Sister Clemmie, shortly after the 1985 Waco showdown, Sheriff Bout well told her, "By the time we finish with Vic Feazell, he will wish he'd never heard the name Henry Lee Lucas." (Sheriff Boutwell denies ever making that statement.)

And, in fact, before long a U.S. attorney was spearheading a full-court-press corruption investigation targeted against D.A. Vic Feazell, an investigation that resulted in Feazell's indictment and arrest on bribery charges on the eve of his reelection campaign. Feazell filed court motions portraying the indictments as "retaliatory prosecution" for his role in exposing the Lucas hoax and putting the prestige of "the law enforcement brotherhood" in question. Feazell fought back, won re-election, and won acquittal from a jury which deliberated for only six hours before rejecting the accusations on the first vote. The Dallas Times Herald later called Feazell's ordeal "a vendetta directed at a prosecutor whose major transgression appeared to be that he held the Texas Rangers and lawmen across the country up to public ridicule by helping expose the hoax of Henry Lee Lucas, a confessed serial murderer who turned out to be nothing but a serial con man." Vindicated, Feazell nonetheless had faced eighty years in prison for his attempt to get to the truth about that prostitute murder, and his promising political career was derailed.

El Paso judge Brunson Moore—the man who presided over the final Texas courtroom battle over a Lucas confession and threw it out of court in December 1986—contends that there's "not one guy who's stood up to the task force" who hasn't suffered retaliation from the lawenforcement brotherhood. What disturbs Judge Moore at least as much is the failure of the criminal-justice system to follow up on the hoax revelations and reopen all those murder cases closed by Lucas's confessions.

A particularly dramatic example of this came to light just two days after my second visit with Lucas on death row in June.

An A.P. dispatch in a Dallas paper datelined Salt Lake City reported that "police say the books will stay closed on three Utah murders attributed to Henry Lee Lucas even though... a 1986 Texas attorney general's report—which Utah lawmen say they didn't know existed— contains evidence which conflicts with information Lucas gave Utah lawmen. [Italics are mine.]

"In one of the [1978] murders," the story continues, "Lucas claimed he was assisted by Ottis Toole although the attorney general's investigation shows that Mr. Lucas didn't meet Mr. Toole until February 1979."

Investigator Mike Feary of the Texas attorney general's office, who worked on the A.G.'s 1986 investigation, was quoted saying, "Nobody should clear a case solely on a Lucas confession. They should ignore it, and see what else they have."

I called Investigator Feary and asked him if somebody in Texas law enforcement didn't have a responsibility to make sure the 150 or so police departments all over the U.S. who have Lucas's confessions still on the books had at least read the attorney general's report. "There may have been some obligation on our part to contact every agency," Feary conceded. Although his office sent out copies of the Lucas Report to lawmen nationwide, he said, it was the Rangers and the task force who knew which police departments cleared which cases—and they weren't sending out the report to anyone.

They still aren't. In a phone interview Texas Ranger Bob Prince, former co-chief of the Lucas task force, estimated there were upwards of 150 cases around the country which had been cleared "with different degrees of certainty" by Lucas confessions. But Captain Prince told me that the Rangers themselves hadn't actually cleared the cases, they'd just booked the teams of local detectives in to see Lucas. Therefore it wasn't the Rangers' responsibility to re-examine the evidence. Nor did he express any doubt that Lucas was a genuine serial killer.

The Lucas case is one in which the facts seem fated never to catch up to the myth. Not only are the Lucas confessions embedded in the legal system, they've found their way into the dicey "science" of serial-killer psychology. A 1988 book by a Ph.D. in psychology, Serial Killers: The Growing Menace, acknowledges charges that Lucas was a hoax but goes right ahead and includes him in its profile of the serial killer's psyche, then uses the fact that Lucas fits the profile as support for the belief he really is a serial killer.

The newly released film Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is another case of the media perpetuating the myth without regard to the facts. The film is not a documentary, but it opens with a statement that it is "based on the confessions of a person named Henry, many of which he later recanted." Despite those weaselly words, the film—which also features characters named "Otis" and "Becky"—clearly endorses the view that the "person named Henry" was the real thing: the soulless serial killer of the myth. The mostly respectful reviews, and laudatory articles about the film's insight into the American psyche in places like Film Comment, seem either unaware or unconcerned that the Lucas confessions might be a hoax and that the film serves the propaganda interests of the task force.

Was it all a hoax? Or is it possible that, even if hundreds of the Lucas-Toole confessions were bogus, they may have killed several more people than the two that most students of the case credit Lucas with? When I learned of the new Florida murder cases against Lucas and Toole, set to come to trial this year, it seemed at first as if they might be just as much an anachronism as Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. But in fact at least one of the Florida prosecutions promises to offer something entirely new: a Long-Silent Witness, one who might be able to pin more murders on Lucas and Toole.

Florida lawmen refuse to talk for the record about the new murder cases or the Long-Silent Witness, but affidavits they filed in the Lucas extradition hearing in Huntsville in 1989 tell a fascinating story.

This climactic chapter of the Lucas saga begins with Ottis Elwood Toole. Toole has always been something of a loose cannon in the Lucas saga. Some of his confessions surpassed even Lucas's in spectacular improbability. There was, for instance, his confession to the murder of young Adam Walsh. He was the six-yearold Florida boy who disappeared in 1981, the son of John Walsh, who later became the celebrated host of the crime-stopper series America's Most Wanted. At one point, when Adam was the object of a highly publicized search, Toole announced that not only had he kidnapped and killed Adam but he had eaten him, which was why the body couldn't be found. When the body was found, Toole didn't allow it to daunt him. And, unlike Lucas, Toole never officially recanted any of his confessions under oath. He still gets visits from investigators from all over the country, still "takes cases," although business is not as brisk as it was before the Adam Walsh fiasco.

On June 7, 1988, according to court papers, an investigator from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement visited Ottis Toole in Florida State Prison. The investigator was working on the unsolved 1981 murder of a northem-Florida woman named Jerilyn Murphy Peoples, who was shot dead in her house upon returning from a grocery-shopping trip.

According to the Florida affidavit, Toole "advised" the investigator that "Peoples was carrying bags of groceries and that she was shot with a rifle, thereby taking responsibility for her death along with Lucas. Toole also verified that [his nephew Frank] Powell was present when this occurred."

What's surprising is what happened next in the Florida investigation. On June 30, 1988, an investigator took a sworn statement from Frank Powell III, who "advised that he was present during the burglary of the Peopleses' home. Powell further stated that Lucas and Toole are responsible for Peoples's death inasmuch as Peoples surprised Lucas and Toole during the burglary."

This is the potential bombshell in the Florida cases: the emergence of the LongSilent Witness, Frank Powell III, the younger brother of Becky Powell. As an elevenand twelve-year-old, he accompanied Lucas and Toole on their travels. Some of their confessions place Powell at the scenes of their crimes, but Powell has never appeared in any judicial forum to confirm or deny what he's said to have seen, never made a sworn statement in any of the Lucas cases until now. With his sister Becky dead or disappeared, Frank Powell III is the only witness to the Lucas-Toole travels, the only one whose testimony has not been heard.

Throughout the years of the LucasToole confession circus, court orders reportedly obtained by Powell's state guardian had prevented any investigating authority from questioning him about what he may or may not have seen. In 1988, however, when Powell turned eighteen, the protective order no longer applied and Florida lawmen moved in with alacrity to get him on the record. (Powell declined a written request from me for an interview.)

There are a number of questions raised by the outlines of the case against Lucas and Toole as adumbrated in the Florida extradition affidavits. For one thing, school records obtained by the Texas attorney general's office indicate Frank Powell III was recorded "present in school" in Jacksonville on the date of the Peoples murder. It's not impossible that he could have slipped away from school to join his uncle Ottis, Henry, and Becky for a four-hour drive to the Florida-panhandle killing site—but it's not clear if Florida investigators were even aware of the problematic school records when they questioned Powell. Nonetheless, armed with the Toole and Powell statements about the Peoples murder, the investigators proceeded to death row in Huntsville. There, they maintain, on July 7, 1988, long after he'd stopped confessing to all other crimes, Henry Lee Lucas proceeded to confess not only to "involvement" in the Peoples killing but also to involvement in two other unsolved Florida murders within a three-month span in the same northem-Florida area.

This, on the face of it, is a shocking turnabout. Down on death row I asked Lucas, "What gives here, Henry? I thought you'd stopped confessing, but here in these affidavits they say: Henry Lee Lucas has given admissions about details of this crime that only the killer could have known."

"I gave them no confessions, no details whatever," he said flatly. "I am not guilty and I will prove it in court."

And then there is Ottis Toole. Curious about where Uncle Ottis stood on these and all the other Lucas cases, I decided to try to speak to him. I wrote to Toole and asked him if he'd agree to be interviewed. What followed was one of the most bizarre encounters I've ever had.

Florida State Prison at Starke (an hour west of Jacksonville) is a forbidding place; it was in the news most recently as the site of an electrocution malfunction, the one where flames shot out from the condemned man's head. I had to pass through four sets of gates before being led to the small conference room where I was to meet with a handcuffed Ottis Toole.

Toole is a formidable-looking fellow— a gaunt, cadaverous six-footer—who appeared, on the surface, menacing enough to be the top-dog serial killer he claimed to be, until halfway into our interview, when he recanted all those claims. The fact that Toole speaks in a lisping, Capote-like southern drawl doesn't detract from the peculiar aura of menace about him. Quite the opposite.

The turning point in my talk with Toole was something I read to him—a passage from a book called Hand of Death: The Henry Lee Lucas Story. It's a schlocky "authorized" biography written at the height of the confession spree, and it recounts with complete credulity all the most ludicrous Satanist-cult ritual-murder and cannibalism tall tales Lucas was peddling back then.

"If I had the book I could tell you what-all was what about Henry Lee," Toole told me at the beginning of our interview.

Now, as it happened, I had acquired a copy of Hand of Death from Sister Clemmie—to whom it was dedicated and who is mortified by its semi-porno sleazoid style.

I decided to ask Toole some questions about the book.

This is how it went at first:

"Was there a Hands of Death cult, Ottis?"

"Yeah," he said with a big, disingenuous grin.

"Did you commit killings for it?"

"Something like that," he said with that same grin.

"Did Henry commit killings for the Hands of Death?"

"Yeah." Grin.

"How many?"

"Quite a bit." Grin.

"And how about you?"

"Quite a bit."

He stuck to that line until I quoted something from the book about the fate of his niece Becky Powell.

"The book says you cut up the body of Becky."

"And ate her?"

"Did you?"

"No."

"So that's a lie?"

"Yeah."

My next question about the Hands of Death seemed to be a turning point.

"Did you ever go to a Satanist assassination training camp in the Everglades?"

"Yeah."

"You did?"

"Really," he said, suddenly shifting. "That whole fucking book is lies."

"So what is the truth?"

"What is the truth?"

"Yeah."

"There ain't no murders," he said, laughing.

"No murders?"

"I dug up all the information playing them, digging all the information out of them."

"How would you do that?"

"A lot of [investigators] just walk in and throw the shit in front of you."

"So these Florida murders, they're lies, too?"

"Uh-huh, they're lies, too."

"How come you kept confessing?"

"I.. .1.. .said, 'The hell with it, I ain't never gonna get out—[I've got] twentyfive mandatory years.' "

"Why did you suddenly decide to give them [the Florida cases] up? Was it because no one had come to you for a while?"

"It was the way we could play."

"You guys did play with the system."

"We had the whole United States in an uproar, the biggest uproar in history," he said, recalling the heyday of the Lucas-Toole serial-murder circus. "We was carrying all of them on a wild-goose chase seeing how much money we could get them to spend on it in all the states."

Toole chuckled merrily over the tales of cannibalism and necrophilia they'd told.

"We threw in the filth; filth is what makes the books sell. They say I eat people, I fucked the dead."

In addition, he told me he had lied when he claimed he'd met Henry in 1975—it wasn't until 1979, he said— which would invalidate once and for all the Lucas-Toole confession to the murder of the Lemonses' daughter in 1975. He also indicated that he and Lucas were actually at work in Jacksonville, a thousand miles away, when they were supposed to be murdering "Orange Socks" in Texas—a killing Lucas may yet be executed for. He said he was going to tell the truth from now on.

Needless to say, Toole's statement alone, sworn or unsworn, about anything has little compelling probative value at this point. Press reports, citing Florida officials, indicate he's recanted before. As Texas investigator Mike Feary says of all cases involving a Lucas-Toole confession, "They should ignore it, and see what else they have." Florida investigators still seem to have something else in one of the three upcoming murder trials of Henry Lee Lucas: the Long-Silent Witness, Frank Powell III. Whether he will be enough to resolve the question remains to be seen.

But what about all those other Lucas cases—will they ever be resolved? What about all those murders in places like Utah, where obviously false Lucas-Toole confessions remain on the books and local authorities don't know or don't care that the hoax has been exposed?

I put that question to a "major-case specialist" within the F.B.I. who was familiar with the Lucas affair. Shouldn't action be taken to reopen those cases?

Exactly, he said. If the attorney general's report is valid, then what's happening is that there are murder cases out there that are not being investigated, and the perpetrators are going free.

But, he added, the F.B.I. has no jurisdiction to intervene in local investigations

of murders. The only remedy, he suggested, lies with the attorneys general of those states which have Lucas confessions on the books—they could take responsibility for undoing the damage on their turf and reopen the cases. But he didn't sound optimistic about that prospect.

In fact, the only hope of ever setting the record straight may lie in a suggestion Joyce Lemons made to me: the families. If the families of the victims in Lucasconfession cases were to pressure local detectives and state attorneys general the way the Lemonses did, then, case by case, truth might be separated from falsehood. (The Lubbock police department has reopened its investigation of the Lemonses' daughter's murder.)

But, Mrs. Lemons told me, she'd often found herself shocked when she'd tried to enlist other families in pressing for the truth about the murderer of their loved ones.

"You know what they'd say?" she asked me. " 'It doesrit matter.' "

"It doesn't matter that the real killer's gone free?"

" 'It doesn't matter. It won't bring our child back.' For God's sake, I know I'm not going to get my child back, but I want the person who really killed her to be the

one to pay. After all, he's. . .these people are still out there. And they'd just say, 'Well, it's over.' "

She'd put her finger on the nature of the staying power of the Lucas myth, the reason, after repeated exposures, it just will not die.

"It's over." The relief in those words, the inexpressible comfort of closure— even by a false confession—is something the families, and the lawmen who originally closed the cases, cling to with a death grip when confronted by the alternative: a reopened case that may never be closed, a reopened wound that may never heal, a death unsolemnized.

Henry Lee Lucas filled a lot of needs with his confessions. Indeed, the serialkiller myth offers a perverse kind of comfort, however false, to the national psyche. It offers a vision of America in which Lucas, the lone slayer of, say, 350 innocents, is safely locked up, heading for a date with the executioner. Which is far less threatening than the vision of America without the Lucas myth: an America in which 350 vicious killers are out there on the loose, with one free murder already under their belts, cruising the highways even now, looking to see if they'll get lucky again. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now