Sign In to Your Account

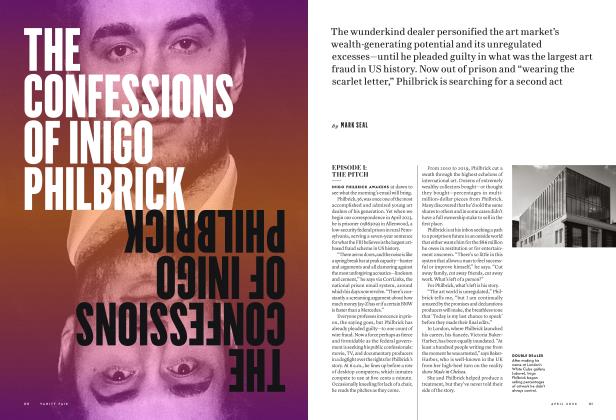

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPARIS CLOUT

Claude Berri, director of Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring, is among the most influential filmmakers in Europe. But recently he sold off half of his production company to indulge his newest passion: assembling what has quickly become one of the most important private modern-art collections in the world. ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST reports from Cannes and the Rive Gauche

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

He needs tendereness.Not an emotion in lavish supply in the movie business.

The bar of the Majestic Hotel is one of the choicest venues during the Cannes Film Festival. Security men with more than their due ration of bone in their faces check nonresidents for festival passes, and it is a safe bet that most of the crowd in the bar will be movie folk. The two pretty young women at our table were researching the room with avid eyes. "That man," said one, indicating a fellow with a ponytail, "he is a famous actor, no?"

No, I said apologetically. A natural mistake. Hollywood people do tend to look alike. The women's glances skittered on and on, like flat stones bouncing over the bright bay.

Neither the two women nor the deal-makers who were circling around them paid any attention to the man who was walking toward the door with a quick, stiff-legged strut through the throng a few feet from the table, carrying a bottle of vodka. He was slight, middle-aged, balding, and had a look of melancholy resignation on his face, like somebody who has lost an adored but aged pet. He came up to me. We exchanged a few words—the vodka was apparently a present for a Russian director—and he slipped away.

I wondered whether to point out to the women that the man they had ignored had more heft in Cannes than America's two most ballyhooed contributions to the event, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Madonna Ciccone, combined.

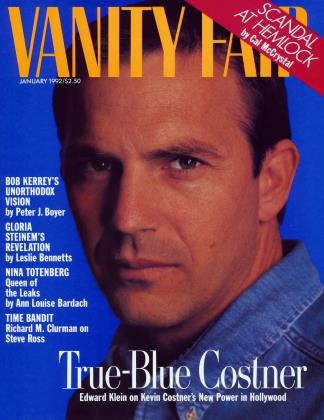

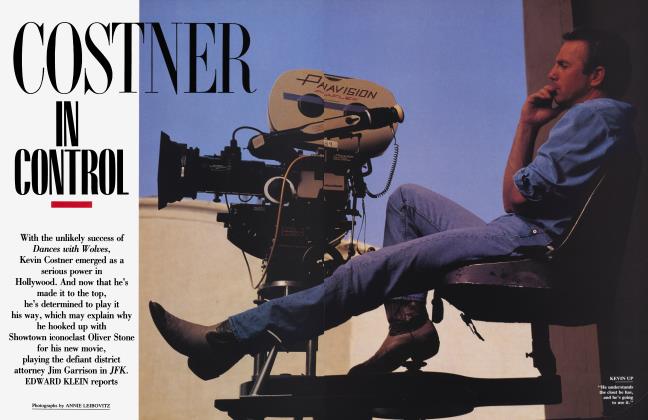

Claude Berri is an outstanding actor, director, and producer; he directed Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring, which restored some luster to France's flagging film industry and which were two of the most successful French films in the United States ever, and he has produced movies for other directors he admires, such as Jean-Jacques Annaud's The Bear and Milos Forman's Valmont. A subsidiary of Berri's Renn Productions distributed Dances with Wolves in France.

Uranus, the most recent movie that he has directed, deals with one of France's uneasiest years, 1945, when the vanquished became the victors. It boasts a wonderfully almostover-the-top performance by the inevitable Gerard Depardieu, and was a solid hit in France. In October, Berri opened something else—a private exhibition space in Paris. It will enable him to show part of what is certainly one of the most extraordinary collections of avant-garde art in France—indeed, one of the most extraordinary in the world.

Six years ago, Claude Berri wouldn't have recognized a piece of avant-garde art if he stubbed his toe on it. It happened so.

Berri had always enjoyed looking at art. "I like Art Deco," he told me. "I would always have two or three pictures. Nothing important, but I needed to look at them in the light. The relationship between the paintings, the light, and myself, that was what was important."

Berri's favorite painting was by Tamara de Lempicka, the Art Deco artist who glides on the fringe of camp without losing a sort of crystalline allure. It showed two young girls. This, along with much else, including a watch, which his mother had given him, was stolen from Berri's ChampsElysees apartment in August 1985, while he was in Provence simultaneously filming Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring. "It annoyed me. I loved this painting," Berri said.

The loss of his art haunted him. The Provencal movies were based on a two-part novel by Marcel Pagnol, so Berri wasn't reading any fiction. Instead he began to immerse himself in a heap of books on a subject about which he had only vague general knowledge: modem art. The film unit returned to Paris in November to finish the movies. "Every day I went to galleries, to museums. I looked. I knew nothing. I knew nothing!"

He found himself another Lempicka, and bought it, but this did not remotely satisfy his craving. "Like Jeanne d'Arc, I had a vision," Berri said. "The theft was destiny! I suddenly had to look at paintings. I made a decision. I had no money in my pocket. But I had my company."

At the time, Renn Productions was worth $50 million, by Berri's own estimate. At fifty-two, he decided to sell off half of it to indulge his new obsession.

Tt actually was not odd that Berri had been unrecognized by the stargazers and the mostly American movie traffickers in the bar of the Majestic. There are, of course, always two Cannes film events going on at the same time: a Hollywood festival—meaning the studios, "the majors," as the locution goes—and the rest.

The big studios know they stand to lose a great deal and gain little by submitting their megahit wannabees to the very untender mercies of the Cannes jurors. (Interestingly enough, the 1991 jury was headed by Roman Polanski, whose own Hollywood career ended abruptly when he took it on the lam rather than face charges of having had unlawful sex with a thirteen-year-old girl in Los Angeles in 1977. Polanski has had only one film success since, and that was Tess, produced by Claude Berri.) But the Hollywood studios, if prudent in what they put on the festival screens, are otherwise ubiquitous. Deals are hawked. Producers within yelling distance of one another on Wilshire Boulevard dig into the langouste on the Carlton terrace. Arnold Schwarzenegger showed up, not, of course, with Terminator 2, supposedly the most expensive movie ever made—at $ 100-millionplus—but to promote a restaurant chain. Madonna was there, but to promote herself via her documentary, Truth or Dare.

This is not to say that North American movies are not shown at the festival, just that the films chosen are "serious," or have been shot on a modest budget, or have a strong personal style, like sex, lies, and videotape, which broke through at Cannes in 1989, or Ethan and Joel Coen's Barton Fink, which won the 1991 Palme d'Or, or Spike Lee's movies, which seem to be permanent, unofficial runners-up.

This is the festival where Claude Berri is an unobtrusively dominant presence. It is to the point that he was in Cannes to promote the interests of ARP, which stands for Auteurs-Realisateurs-Producteurs, meaning filmmakers who can function as writers, directors, and producers. Berri says that this group was the brainchild of Frangois Truffaut, a close friend and the best man at his wedding, but after Truffaut's death it was Berri who brought things to fruition. Talking of directors and producers, Berri has observed that directors have the moral right, but producers have the economic clout. "We producer-directors have both," he added. The trade magazine Le Film Franqais has noted that Claude Berri ''does not like to have positions imposed on him." In France, by the way, directors have the right of final cut by law. They, not producers, have the ultimate control. Now, there's a concept to send blood pressure skyrocketing in Hollywood.

"Berri is not American. He is pure French product."

Onstage at Cannes for a tribute to the late director Jacques Demy, Berri looked pensive, a bit sad. It was appropriate, but, actually, Berri almost always looks pensive, a bit sad. It isn't the glumness that condenses around Woody Allen like a mist on a cold bottle, more the look of somebody who hopes things will turn out O.K. but isn't taking any bets on it. I mentioned to him that he usually looked—that euphemistic term—preoccupied.

"Like I am always thinking?" he asked. "No, no, no."

He tapped a pack of Lucky Strikes. "I am thinking about the cigarettes. It's the last one," he said.

It was a rare evasion from a filmmaker who has been remarkable in inviting viewers into his life in a number of autobiographical movies. In the first of these, The Two of Us, he shows how as the seven-year-old son of a Jewish couple in Paris, a Polish furrier father and an illiterate Romanian mother, he was sheltered during the war years by an anti-Semitic old grouch (played by the great Michel Simon). In Le Cinema de Papa, which Berri directed when he was thirty-six, he takes us through some childhood scenes and examines his relationship with his volatile father, called in the movie, as in actuality, Henri Langmann.

Continued on page 134

Continued from page 97

Playing himself with a gentle humor and self-deprecation, Berri re-enacted his rejection of a future in his father's Paris shop, and relived some early misadventures in both his love life and his career. These included being offered a part in an American movie—"O.K., Claude, we'll make a star out of you! A star!"—and subsequently being tossed out because of his "inability to speak the language of Shakespeare." (Not yet wholly corrected. Our conversations were bilingual, despite my own clumsiness in the language of Moliere.)

The movie ends with young Claude, dreaming of success, planning to make a movie starring his father, a project thwarted by his early death. Was this true?, I asked incredulously.

"Everything in the film is true," Berri told me.

The last shot is of his father's gravestone. Why had he himself taken the name Berri?

"When I wanted to be an actor, I wanted a name that was easy to remember. A French name," Berri said. "Like Maurice Chevalier."

Real life, reel life. At eighteen, Berri appeared as a silhouette in Jean Renoir's French Cancan, and then proceeded

through tiny movie and theater roles and produced his first play, with his father's help, at twenty-five. A fiasco. Four years later, he directed a comedy short, The Chicken, which won him an Academy Award. It did not impress him until he discovered this was the same thing as an Oscar. The Chicken had been made for $10,000, which had been borrowed from two friends, and Berri produced it himself. This was the beginning of Renn Productions, named after Katharina Renn, who lent Berri some of the initial capital, and also the beginning of his first marriage, to Anne-Marie Rassam, a young woman bom in Beirut.

The Two of Us was Bern's first feature, and it was a huge success in France. People were beginning to notice that the serious, soft-spoken thirty-two-year-old was capable of formidable focus and was possessed of highly defined ambitions.

In 1968, the Czech director Milos Forman, who had been widely praised for Loves of a Blonde, got out of Prague just ahead of the Russian tanks. A Paris apartment was found for him by Berri. He began work on a project for Paramount to be called Taking Off. He would direct and Berri would produce.

One day, Forman, in great excitement, played Berri a record album of the new musical Hair. He wanted to write the show into his script for Taking Off. This was the sixties, remember. Berri thought that was a terrific idea, and took it to Paramount's then head of production, Robert Evans, whose reaction, according to Claude Berri, was "Why not? If you get the rights."

Berri called Hair's co-authors, Gerome Ragni and James Rado. They asked for $1.5 million, plus 10 percent of the gross. Berri took the proposition to Evans. "He said, 'Why not? If you get the rights. . . ' "

Ragni and Rado were in a Chateau Marmont bungalow on Sunset Strip. Berri and Milos Forman flew out. It was Bern's first visit to Los Angeles. "We had a one o'clock appointment. But nobody was in the bungalow," Berri said. "After about twenty minutes a nude girl walked through the lobby. We waited some more."

The writers finally showed up, but not alone.

"They were with a guru. He was very important. He was very kind. We took coffee. After ten minutes, they said that the guru must play the tarot to see if it is good that Milos direct Hair and Claude produce," Berri remembered.

"So we looked at each other. The guru made the tarot, and it was terrible. Terribly bad. The tarot said no! No question that Milos direct and Claude produce. No one million and a half. No 10 percent of the gross. Nothing. "O.K. They were very kind. Ten minutes later they said try again. So the guru made the tarot again. And the second time it was worse than the first." The pair left the world's movie capital empty-handed.

In 1975, Berri entered into partnership with his brother-in-law, Paul Rassam, and began building Renn Productions into an ever more powerful entity. He was doing so using methods that would be considered fairly feckless in the American entertainment industry.

It seems telling that the French language does not even have a word that means "entertainment" in the above sense. "When Claude produces a movie, he chooses the artist. Then he removes himself from the scene. He does not interfere," one French-film-industry person remarked. He simply lets them get on with it, even when—notably as with Polanski's high-budget Tess—failure could imperil his whole enterprise. Berri's longtime sound mixer, Dominique Hennequin, told me that he may show up only three times a week to see how work is progressing.

What if things get unglued?

"There are no confrontations. He just looks more sad than usual."

A technician said, "// a besoin de tendr esse."

He needs tenderness. Not an emotion in lavish supply in the movie business.

Berri has also from time to time returned to his first profession, acting. In Patrice Chereau's The Wounded Man, a strong, dark-toned story of an adolescent boy's embrace of gay street life, Berri appears in a short, powerful role as "The Client." He behaves obnoxiously, shows his fat, hairy little turn, and his last line is "Let me suck you off." In the unlikely event that Hollywood remakes The Wounded Man, I somehow can't see its producer taking this part.

Milos Forman ended up making Hair ten years after the Chateau Marmont meeting, but not with Berri. After the Pagnol movies, though, Berri produced and Forman directed Valmont, the second of the two screen adaptations of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, released in 1989. The box-office returns indicated that Berri and Forman should have listened to that guru. By the time of Valmont, though, Berri had sold 50 percent of Renn, and was launched into the world of Art.

The Paris headquarters of Jerome Seydoux, the man who bought half of Claude Berri's company in 1986, is on the Boulevard Malesherbes, a short walk from the Place de la Madeleine. You cannot actually see the neoclassical Madeleine itself right now. What you see is a huge billboard bearing a scale graphic showing the way the Madeleine will look when restored. It seems very appropriate to the brand-new Europe, of which Jerome Seydoux's company, Chargeurs, is a successful part.

Seydoux is trim, in his later fifties, with blue eyes, short gray hair, and the guarded smile of somebody who both relishes and is cautious of attention. His office is hung with three Dubuffets, a Tapies, an enormous Nicolas De Stael. He was eager to talk about Claude Berri, but otherwise reticent. "Family is something which should stay private," he said. "Even if a number of things are known."

A number of things are known. Seydoux is the oldest of three brothers from a Protestant family in Alsace. Their grandfather Marcel Schlumberger made a huge oil fortune, not from drilling or shipping the stuff but from supplying the crucial technology. Schlumberger had a son, Pierre, and two daughters (the de Menils of Houston and New York, also, it happens, deeply involved in avant-garde art, come from another Schlumberger marriage), but a dozen years after the death of the patriarch, control of the company passed to Jean Riboud, an ascetic from Lyons, one of those curious business visionaries tossed up by postwar Europe.

It was Riboud's decision that Jerome Seydoux and his brothers, Nicolas and Michel, should leave the family firm. All have done well enough on their own that they, along with their mother, pop up separately on those French-rich lists that their countrypeople find as fascinating as do the readers of those in Fortune and Forbes. In 1988, for instance, L'Expansion, a business glossy, listed Jerome at No. 15.

Michel, the youngest brother, who was the first one into the media business, started a movie-production company in 1971. In 1974, Nicolas, the middle brother, bought Gaumont, a famous chain of cinemas which also owned studios. Jerome announced that he was not interested in the entertainment field, and took control of Chargeurs, which had huge holdings in textiles and transportation. In 1985, though, President Mitterrand let it be known that he was going to allow one of France's stateowned television channels to be taken private. Jerome Seydoux, who is that very European phenomenon, a liberal magnate, and is close to Mitterrand, acquired the franchise in partnership with the Italian media man Silvio Berlusconi. The new channel was called La Cinq—"The Five." Michel Seydoux began acquiring movies for it. He introduced Jerome to Claude Berri. La Cinq was inaugurated with one of Berri's productions.

What happened then was thoroughly French. Jacques Chirac, a right-winger, became prime minister. He quickly revoked Seydoux's contract, and handed it over to Robert Hersant, the very rightwing owner of Le Figaro. Jerome Seydoux was thus out of the media world. It was at this juncture that he was approached by Claude Berri, who was looking for a buyer for half of Renn.

There was a pause when I asked Seydoux why he got involved. "We thought we could work together," he said finally. "We are certainly not the boss. He has kept his freedom, which I think is very important.

"We can help by giving him and his partners the opportunities to do things outside France. It is a business where you have to look outside. But it is a tricky business, the movie business. It is full of ogres. It is not sufficient to make a good movie." He laughed dryly. "What is marvelous about the association with Claude is that he has ideas. And he is not alone. He has partners. I don't think the ideas should come from me. I'm not so sure I would have good ideas."

Seydoux is now deeply involved with BSkyB, the satellite television network, in which he is a partner with Rupert Murdoch, and which he believes represents the future of European TV. It also, of course, represents a giant market for movies. If the three Seydoux joined forces— "Seydoux Bros.," which Michel once humorously compared to Warner Bros.— would they be the biggest entertainment company in France?

"In movies certainly. But I am not so sure in this business that size is really the answer. "

This is Berri's thinking, too, and very un-Hollywood at that. "But he is not American," Seydoux said. "He is pure French product."

He gave his bray of a laugh.

As I was leaving, we looked at the paintings. There was a Warhol in the outer office?4 Black Marilyns. "I was less modem," Jerome Seydoux said. "Claude helped me become more modern. And still he is more modem than I am."

Claude Berri's Paris apartment is on the Rue de Lille, a handsome, narrow street. The apartment is large, but unfussy. There is a paperback of Zola's Germinal, a future project, and a clutter of toys, the property of Darius, his five-yearold son by his fiancee, Sylvie Gautrelet. (Berri is now divorced from Anne-Marie, although her brother remains his partner.) There is also a present for Darius, a drawing by the New York artist Robert Mangold. Its stark, uncompromising shape and the abundance of art on the wall mark the journey that Berri set out on at the age of fifty-two, just six years ago.

Berri's first acquisitions after cashing in half of his company had been the sort of work that most collectors of modem art begin with: safe, "classical" work. He bought, for instance, an excellent Picasso. His first more personal encounter was with the raw, fierce work of the Frenchman Jean Dubuffet. "I spent a year only interested in Dubuffet," Berri told me. "His evolution." He bought a number of canvases by the artist and forever hung and rehung them, examining the changing effects of the light.

Then Jean de Florette brought him to Manhattan, and Berri was taken to meet Leo Castelli, who, Berri observed, "was fifty when he started his New York gallery." Castelli took Berri to the exhibition commemorating his thirty years as a dealer, which occupied his Greene Street gallery. It was a remarkable show, and it was also Bern's first experience of the American avant-garde. "I think I communicated some pride in what I had done," Castelli told me. "I looked at it without completely understanding it, but one painting pleased me," Berri said. "It was a Twombly." This was Cy Twombly's The Italians, a spare, vibrant piece that had been lent to Castelli for the show by the Museum of Modern Art. "I said, 'Leo! I want a Twombly!'

It was at his second meeting with Castelli that Berri, a man of strong impulses, asked to make a documentary about him. Castelli agreed, and Berri sold the project to La Sept, the French cultural TV channel, and conducted his first interview. Berri did the interviewing himself, and, as his questions indicate, he was still remarkably uninformed about the avant-garde. But he plunged ahead into the art jungle. "He was very fast. It was like in hot fever," says Karsten Greve, the Cologne dealer who in the end found Berri a Twombly.

Inevitably, Berri started by acquiring work that he would later change his mind about—all beginning collectors do—but he very soon alit on the artists who are the core of his collection today. They include Dubuffet, Twombly, the Greek artist Jannis Kounellis, and the Italian Lucio Fontana, best known for slashing and gouging the surfaces of his work.

Berri's collection is most remarkable for its monochromes, paintings that consist of

one allover color. The first monochrome he acquired was by Yves Klein, a Parisian who died in his mid-thirties and who was famous/infamous for such pieces as his Anthropometries, body prints produced by his "living brushes"—naked, paintsmeared young women who wriggled on canvas according to his instructions. His "Monochromes" were panels of pure color, usually in an electric azure which the artist claimed to have copyrighted as "International Klein Blue."

From Klein, Berri moved on to the artist's rival Piero Manzoni, who outdid Klein by making monochromes of no color at all, namely white. It was natural that Berri would also require one of Ad Reinhardt's black paintings. He got one after finding himself seated next to the artist's widow at a dinner at the Guggenheim.

Then Berri discovered the "white" paintings of Robert Ryman.

Ryman, a New Yorker, dislikes having his work described as monochromatic, because he uses other colors along with the white, and it is the ghostly traces of those colors that make his surfaces pulse with life. His touch can be as creamy as Manzoni's, but it is more often austere and feathery. Berri bought a Ryman, took it back to Paris, and hung it. It palled on him. He had reached a level of response where one monochrome was vastly less effective than another.

"Then a woman came up to me at Sotheby's during an auction," Berri said. " 'Do you want a Ryman?' I said yes. She said, 'Come with me.' So we go to this place, and I saw this triptych by Ryman. It was during the night, with electric light, and Ryman you should see in natural light, so when I got it home I was disappointed again."

Berri returned both these paintings to the marketplace and they were sold. Then, shortly before the premiere of Valmont, he went to a Christie's auction and saw the Ryman he wanted. "I put the most important bid ever for a Ryman at auction," he told me, still gleeful. "Two million one! I broke the record!"

Some points deserve to be made here. Various art-worlders deplored Berri's quick resale of the two earlier Rymans as damaging to the market. Others saw the Christie's purchase, which quadrupled the artist's price, as one more late-eighties folly. The art world—including almost every artist—has grown cynical about collectors; a saying of the late great dealer Sidney Janis has been much quoted recently: Scratch a collector and you find a dealer. But Berri is a passionate collector, and an unusual one. "Claude is probably the subtlest collector I have come across in my whole life," Castelli told me. In a time when major collections have begun to resemble one another like so many Benetton outlets, Berri's collection is different. Unalike as the works may be, they share a sensibility, an intensity of feeling.

And there's something else. After the Second World War, New York famously toppled Paris as the world's art capital. Relations between the two art worlds have been bitter ever since. American artists, for instance, were hostile to Yves Klein, whom many regarded as a charlatan, when he came to New York shortly before his death. "Americans don't like French art," Leo Castelli says. "They think it is precious. Too refined."

Claude Berri's collection shows American, French, and other European artists on an equal footing, a very timely thing to do. "It is because it is such a young collection," says the Parisian artist JeanPierre Raynaud. "He knows this history. But it does not matter to him."

Berri finished showing me around his collection, shoving a bolt of striped material by Daniel Buren, the French conceptualise back under a table. We repaired to the kitchen, and he lit a cigarette. "I cannot smoke in there," he said, gesturing toward the main room. Why? "Because of the Rymans."

I asked about the effect of the Great Art Bust of last fall. It has left him unfazed. "The pieces are not for sale," he said. "The market is not my problem. It is not my problem."

We walked downstairs. Berri has leased a disused printworks on the ground floor of the building next to his in the Rue de Lille and transformed it into a small museum, awash with milky natural light. It opened in October with an exhibition of fifty Rymans, five of which Berri owns. The show was installed by the artist himself. Some have caviled that the fledgling museum director has gotten a jump on a major Ryman show being jointly planned by MOMA and London's Tate Gallery. But, then again, why on earth shouldn't he?

Berri's two sons by Anne-Marie are named Julien and Thomas. At twenty, Thomas—who calls himself Langmann rather than Berri—is already a successful actor. Julien is a film director. Berri has been living with Sylvie Gautrelet for eight years. They will marry when he's finished building a house in Provence.

Claude Berri continues to work fullbore at moviemaking. Last year, he appeared as the unappealing title character in Stan the Flasher, a movie directed by Serge Gainsbourg. It was not a success, and Berri told me that his only acting ambition now is a possible return to the stage. He is producing a movie to be directed by Patrice Chereau, who made The Wounded Man. He was to have directed an English-language movie in Hollywood, but abandoned the project. "I was missing too many of the nuances," he says. A Berri production, L'Amant, based on Marguerite Duras's international best-seller and directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, opens in France this month. In September he will start shooting Zola's Germinal, starring Gerard Depardieu and Miou-Miou.

I mentioned something that had been on my mind. Bern's tastes in art are rarefied, extreme. His movies, on the other hand, are popular movies, albeit personal, and full of heart. You are no Jean-Luc Godard, I observed.

"That is true," Berri said. "That is true. Perhaps I shall make such a film one day." But movies, he feels, should have a wide popular appeal. "Movies are my life," he said. "I love painting. But probably I was born for the movies."

His acquisitive fever seems abated. "I must stop for a little while because I have no money," he told me. He may sell more shares in Renn to Jerome Seydoux and go off on another splurge, but he isn't certain. "I made a very quick run," he said. "It is not so important for me to collect today. We open the space. I have enough paintings around me to be happy."

Curiously, the stolen Tamara de Lempicka that started the whole thing resurfaced in his life the day before our first meeting in Paris. Two men had gone to jail some time ago for involvement in the theft, but the police were hanging on to the painting until a third suspect was investigated.

One of the jailed men had just been released and sent Berri a postcard. He handed it to me. It carried a sepia scene of Paris life. "I am sorry," the criminal wrote. "I am a painter. I live on Rue Jacob. ' ' It contained a succinct critique of one of Bern's movies—and a request for a job.

"Funny, no?" Claude Berri asked.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now