Sign In to Your Account

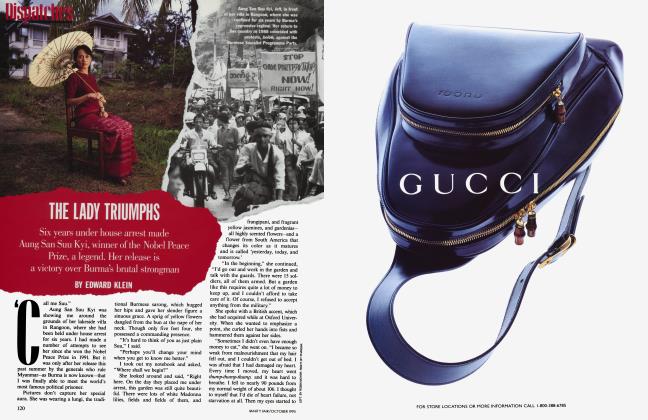

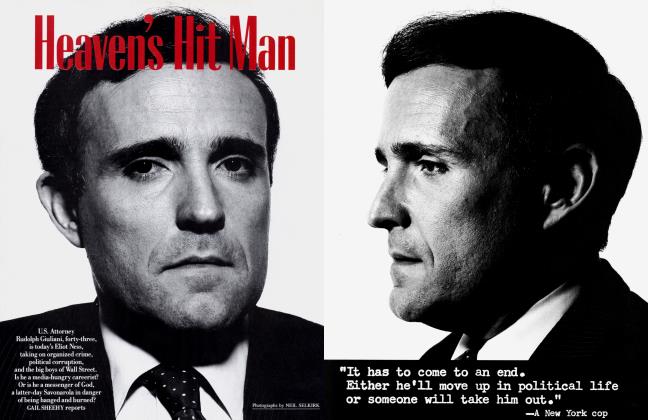

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAll Lips and Lashes

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

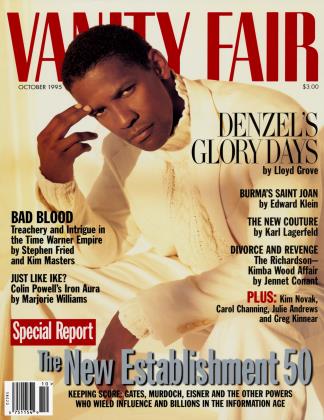

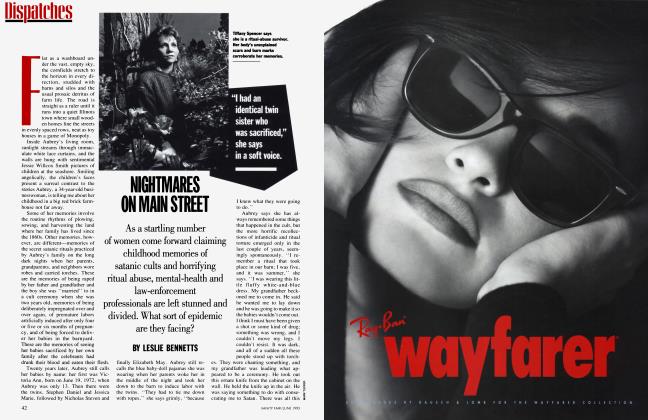

By the time the umpteenth Hello, Dolly! revival rolls into New York this fall, Carol Channing will have given some 4,500 performances as Dolly Levi, a role she originated in 1964. But at 74, the saucer-eyed, baby-voiced Channing is still Broadway's preferred blonde, with a standing ovation at every single curtain. Joining the road show, LESLIE BENNETTS meets the tough customer underneath the cotton-candy wig

Back in the mid-1980s, a graffiti artist spray-painted GOD SAVE US FROM HELL! on an L.A. traffic ramp. Such earnestness didn't survive long; another commentator soon arrived with decidedly different concerns. From then on the graffiti read, GOD SAVE US FROM HELLO DOLLY REVIVALS!

So far, God is no match for Carol Channing; yet another national tour of Hello, Dolly! is now barreling around the country. And judging from the crowd tonight in Salt Lake City, you'd never guess such cynicism existed. By intermission the woman in front of me is practically in tears—and we haven't even gotten to the title song yet. When Channing appears at the top of that stairway—resplendent in a jeweled scarlet gown, her platinum head quivering with red plumage—her voice sounds as if she'd been gargling with Drano, but it doesn't matter.

"Wow, wow, wow, fellas—look at the old girl now, fellas!" she growls, and the audience erupts. Look at the old girl, indeed. She's 74—and still pulling them to their feet.

The reason why is written all over her. By the time Hello, Dolly! hits Broadway in October, Channing will have given nearly 4,500 performances as Dolly Gallagher Levi, a role she originated in 1964 and has played ever since in one revival after another. But you'd never know it; she still revels in every moment. As she tilts her upturned face toward the balcony, it is suffused with a look of yearning so intense it gives you goose bumps. The applause surges, washing over her like a wave; you can almost feel her drinking it in. For Carol Channing, that kind of approval is like oxygen; it's what she lives on, and always has.

And Hello, Dolly! remains the most reliable source of a fix. The show won 10 Tony Awards, including best musical; as best actress in a musical, Channing even beat Barbra Streisand, nominated for Funny Girl. But then Streisand broke her heart by landing the starring role in the movie version of Hello, Dolly!, just as Marilyn Monroe had devastated Channing years earlier by sashaying off with the role of Lorelei Lee, which Channing had originated on Broadway, in the movie of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Equally disappointing were most of Channing's later attempts to recapture Broadway; although she had been a smashing success in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in 1949, the 1974 sequel, Lorelei, was a lame rehash that recycled some of the original songs. A dozen years later, not even the pairing of Channing with Mary Martin was able to save Legends!, a turkey that limped around the country for a year but closed before making it to New York.

But Hello, Dolly! is always a sure thing. In person, Channing remains in character, but the character isn't so much the shrewd, calculating Dolly as it is Lorelei, the classic dumb blonde. By the time Channing accepted her Lifetime Achievement award at the Tony ceremony last June, the familiar persona seemed almost grotesque: although she's close to six feet tall in heels, Channing always presents herself as a saucer-eyed, baby-voiced Kewpie doll with cotton-candy hair, a fathomlessly blank expression, and not a brain in her head. It's a bizarre image for anyone out of diapers, let alone a showbiz legend in her 70s. As Channing batted her eyelashes and babbled at the audience, it was genuinely eerie, like watching some animatronic dinosaur that endlessly repeats the same motions. "This is the death of the American theater," murmured one Broadway power player in the audience.

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

Waiting for Channing in her Salt Lake City hotel room, I'm not sure what to expect. The apparition that finally materializes is equally curious, but quite different. When Channing pads in with big red watermelon slippers on her feet, wearing a pointy-hooded fire-engine-red bathrobe with red tights underneath, she's an arresting sight; she looks like a giant elf escaped from Santa's workshop. Her gray hair is pulled up in a cockeyed ponytail, the loopy, off-center kind little girls make before they learn how to get it straight, with flyaway wisps escaping everywhere. When she says hello to me, her voice is still that baby-doll simper, but her eyes are cool and appraising.

"There are two totally different people there," observes Jerry Herman, the composer of Hello, Dolly! and an old friend. "Very early on, she developed a style; it's her stage persona, and she doesn't want to give it up. But in private, I have long, intelligent, meaningful conversations with her."

Unlike Channing, her husband appears very much the distinguished grown-up, silver-haired and impeccably groomed. "You've come all the way to Milwaukee to see us—so nice of you!" booms Charles Lowe, extending his hand.

"We're in Salt Lake City," I remind him. He shrugs. Last week it was Costa Mesa, next week it's Milwaukee: What's the difference? There will always be another town waiting up ahead. If eight million people have seen Channing play Dolly so far, why, that still leaves more than 240 million to go!

The inevitable question is why. The money ain't bad, of course; by the time the current tour ends, Channing will have made more than $5 million on this production alone.

But no one who knows her believes that the motivation is purely financial. After all, the rigors of eight performances a week are daunting for performers in their 20s—and Channing works like a packhorse all day as well, giving interviews to every local media outlet, lunching with critics, chatting up women's groups, even delivering the weather forecast on any television station that will let her. "Charles calls it 'selling the jams and jellies,'" says one colleague. "They make sure every seat is sold."

The Lowes' focus is so single-minded, their dedication so consuming, that there's nothing left over for any other kind of life. They don't take vacations; they have no other pleasures or pastimes. So why does Channing continue to drive herself so hard?

"It's happiness," she says simply. "What am I supposed to save myself for? Something I don't do that well, like tennis? Sitting on the beach? This is pleasure. I'm using every faculty my brain and body can give me, to the hilt— everything I've got that is strong and healthy. Now, what on earth is better than that? That's magic!"

When she's not performing, she's miserable. "I'm useless," she says darkly. "I have lots of faults, and they matter. All I've got is me and my own faults. There's no other excuse for my existence. If you dwell on yourself, it gets sickening."

"You want my autograph?" she asked. And then she screamed, Well, write me?

Her dedication is legendary. Until she interrupted the current tour to fly to New York for the Tonys, Channing had never missed a single performance of Hello, Dolly! She will finish a show no matter what happens. When she was touring in Legends!, she had a scene that involved a vacuum cleaner, and one night Channing, who was then in her mid-60s, tripped over it.

"She bounced back up and finished the play," reports Gary Beach, an actor who was in the show. "She never left the stage, and you'd never have known anything was wrong. I had no idea. But at curtain call I reached down to grab her hand, and she said, 'Don't— my arm's broken.' And it was. They took her to the hospital, got it set,

and she finished the run in a cast." The Lowes used even that to Carol's advantage. "The stage manager would make an announcement before the performance started: 'Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Channing has broken her arm,'" Beach says. "The whole audience would go, 'Ohhhhhh!' And then he would say, 'But Miss Channing insists on going on this afternoon.' And the audience would go, 'Ahhhhhhhh!' So we start the play with a cheer; you've already got 2,000 ladies on your side."

Channing's professionalism was most sorely tested during the ill-fated tour of Legends! Among the show's many problems was the fact that Mary Martin, then entering her dotage, couldn't remember her lines. Channing coped heroically by learning all of Martin's lines along with her own, and improvising cues to jog her co-star's memory. "It was totally valiant," says Beach. Occasionally, however, Channing's exasperation would get the better of her, and she took to snapping at Martin onstage. "Suddenly you'd hear, 'Well, you really blew that laugh!'" Beach reports.

Getting the laugh has always been the most important thing in the world to Channing, ever since she stepped onto a stage for the first time. She was seven years old, and her home life was tormented, but what she discovered that day at a school assembly changed her life forever.

"The first time onstage, I soared," she says dreamily. "The first time you find out they're laughing, and they think it's just as funny as you did—suddenly I was soaring. From the time I was nine I was going to Saturday matinees, and, boy, that fed me! Then I'd go back to school and do Ethel Waters, do Fanny Brice. I was unafraid onstage. The safest place in the world is the middle of a stage. Nobody can get you."

That wasn't the case at home. Channing grew up in San Francisco as the only child of a renowned Christian Science lecturer, George Channing. She adored her father, but her mother was a nightmare. Part of her recoils from revealing the truth about their relationship—"I don't like people who don't like their mothers," she says disapprovingly—but she can't help it. It makes her nervous to be talking about real feelings, and she keeps trying to divert the conversation, offering up the imitations she does so well: Tallulah Bankhead, Ethel Merman, Marlene Dietrich. But no matter what the ostensible topic, Channing keeps circling back obsessively to her mother.

The portrait she paints is of a viciously subversive woman who went to almost insane lengths to tear her daughter down, gloating over her failures and sabotaging her successes. "She was crazy," Channing says flatly. "Nobody understands if you're frightened of your mother. She would go to school and tell the teachers things I never said about them. The teacher said, 'Why do you lie like that?' I was absolutely petrified. I didn't know how to combat it. My mission in life was to hide the fact that my mother was crazy. I was never allowed to have friends. She completely possessed me. I do not understand my mother to this day; I don't know what was the matter with her. She was jealous of anything I did. She would laugh because she talked the teacher out of giving me the oratorical award!"

As she says this, Channing maintains her habitual expression of blank amazement, but there is such venom in her voice that it makes me shiver. Little Carol worshiped her father, a big man who always had a weight problem. But her mother even bragged about trying to hasten his death. "She said, 'If I keep feeding him all this fat and starch, he'll go like that? " Channing snaps her fingers crisply. "My father was stuck with her; he couldn't get away. He was devoted to his religion. I could hear the fights; I begged them, 'Can't you get divorced? It would be so much better if you could get away from each other!'" But they stayed together, and one day George Channing, returning to America after a European lecture tour, suffered a heart attack on the airplane and died—"like that!"

By then, however, Carol had found a haven elsewhere. A Bennington dropout, she had already married early and unwisely, not once but twice. Why did she marry so young? "I didn't know how to make friends," she says plaintively. "I'm always frightened and self-conscious."

Husband number one was a writer she had met on the Borscht Belt; she says he had a drug problem and later "died of drugs." By that time Carol had divorced him and married a football player ("Not a good one," she assures me) who turned out to be a hopeless alcoholic. "It made my mother happy, the two bad marriages," Carol says bitterly. "It gave her power. It made her happy that I was a failure."

Although Carol's second marriage was brief, to her enormous dismay she got pregnant. "I didn't 'decide' to have a child; it was all a pure mistake," she says grimly. "I was supposed to go to London and do Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and I couldn't do it. I was upset, but I could not kill George Channing's grandson. I sure loved my father; I guess I made a deity out of him. But getting pregnant sure knocked me silly. I knew how ambitious I was."

After her son, Channing, was bom, Carol approached child-rearing as idiosyncratically as she did everything else. "I'd just keep talking to him, telling him, 'Now, I have to go to work, Chan—you have to understand this,'" she explains reasonably, as if it were entirely logical to expect an infant to assimilate such information and accommodate his mother's needs accordingly. "I said, 'Chan, I can't spend as much time with you as we would like; you have to help me with this. I've got to get ready and go.'"

And she went, leaving Chan behind, often for long periods of time. When Chan was three, salvation arrived in the form of Charles Lowe, a never-married television producer who worked for an advertising agency and had a close professional relationship with George Burns and Gracie Allen. Although Carol was still married to the football player, she was instantly smitten with Charles.

"I knew it the moment I met him," she says fervently. "I feel it's a miracle; Charles's and my relationship is a miracle. He knew how to get me out of this nightmare marriage, and he got me out of it. Charles was funny. I never laughed so much in my life. My life opened up like crazy. He swept me into the Burns family." She sighs rapturously. "To be sleeping with the person you want to be sleeping with and not fantasizing about another person— Oh, my God!"

Charles stepped right into place as Chan's father—and with Carol's grateful acquiescence, he took charge of her career as well. "Gracie Allen said to me, 'Just let him do all the work. You just take care of the show,'" Carol recalls. "I do everything he tells me to do."

Most female stars bemoan their inability to make a marriage work; their husbands always end up resenting them and envying the limelight. Not Charles Lowe; he virtually insists on public self-effacement. "Whenever we go out to a theater event, Charles, instead of taking Carol's arm, pushes me to take her arm, because it's more interesting for the cameras to have the composer and the star," reports Jerry Herman. "He walks behind us. He's been doing this for 30 years."

"He's hell-bent on the goal," Carol explains, "and I'm hell-bent on the goal: Get that theater filled up! He's betting on me. He's giving his whole life to me, and I'd better come through. I can't let Charles down. I can't fail him, let alone fail myself."

When Charles Lowe and I sit down to lunch, he looks so immaculate that he could have stepped out of a men's fashion magazine. From his white hair to his white turtleneck to his white pants to his white shoes, everything is perfect.

Lowe has always been the kind of man who takes care of the smallest detail. He writes every word Carol says in public, from her nightly curtain speeches to her pitches for fake diamonds on QVC. He's working the phones by nine every morning, managing Carol's career and plotting her future. He attends every single performance, watching Hello, Dolly! each night as attentively as if he had never seen it before—leading every round of applause, laughing louder than anyone, leaping to his feet to start the standing ovations. "He's Mr. Perfect Audience," says Gary Beach. "His performance is every bit as good as Carol's."

Carol's performance absorbs the Lowes endlessly; they never get tired of refining it, and Charles's pursuit of perfection is all-encompassing. When Carol's old friend Maxine Mesinger went to see the show recently, Charles indignantly reproached her for anticipating a laugh line. "He said, 'Goddamn it, you're stepping on the laugh!'" reports Mesinger, a columnist for the Houston Chronicle.

The Lowes' relationship is a perpetual source of amazement to friends and colleagues. "Charles puts her together like a Tinkertoy," marvels Jean Kerr, the author and wife of retired New York Times theater critic Walter Kerr. "You can't talk about Carol without talking about a Charles," attests Barbara Walters. "I remember once having Charles on Not for Women Only. Charles talked about Carol as if it were General Motors and she were a product that had to be kept new and wonderful. It isn't just that he loves her; they're a team. He makes it possible for her to go out onstage."

At times Charles's relentlessness, not to mention his penchant for referring to his wife as "Miss Channing," proves overwhelmingly irritating to her colleagues. Fortunately, he is not without a sense of humor. During the " Legends! tour, says Gary Beach, "Charles was in the company manager's office one day, ranting and raving about this and that—'You can't do that to Miss Channing!' The company manager finally said, 'Charles, don't be such an asshole!' Charles drew himself up and said, 'What—and ruin my reputation?' He knows exactly what he's doing." Charles's unusual devotion is echoed in that of Carol's son—an outcome which, in retrospect, seems miraculous. Accompanying her everywhere is a framed Mother's Day card he sent her, bestowing a Tony Award for "Best Mom." "In a Difficult Balancing Act—Lifetime Achievement," reads the card, which he drew himself. "Mom—Here's your award for your other accomplishment, less ballyhooed maybe, but no less important. Happy Mother's Day!"

"She's a major, major diva... There's this really tough woman you see behind closed doors."

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

These days Channing Lowe leads a seemingly normal life as an editorial cartoonist for the Fort Lauderdale SunSentinel, but his childhood was distinctly unorthodox; he was always being stashed in some hotel with hired help while his parents gallivanted around the country, and he was packed off to boarding school as soon as was practicable. Despite the long separations, Carol seems to view their family life as warm and wonderful. "Chan got to visit us on every vacation," she says brightly. "Wherever we were, we'd just fly him in."

Chan, who is now 42, insists he didn't feel bereft. "I never went for more than a few months at a time without seeing them," he says earnestly. "We were on the phone constantly. Both my mother and Charles were very involved parents. Even though they couldn't physically be there, they made sure I was taken care of. I never felt like I was being shunted aside as a second-class citizen to The Career."

Given how badly the children of many stars turn out, the Lowes' friends have long been impressed with Chan; he not only stayed out of trouble but also managed to create a successful professional identity of his own. "He's a really good guy," says Susan Estrich, a California law professor, columnist, and television commentator who is a close friend of the Lowes'. "He's smart, he's serious, he's substantive, he loves his parents—he struck me as a real grown-up. He turned out fine."

Nor is Chan the only evidence of Carol's essential goodness. "I had a sister who was slightly mentally retardedjust enough to ruin her life," Barbara Walters tells me. "She stuttered badly, but she loved people in show business. Carol and she didn't just become friends—Carol would take my sister away on vacations with her. Carol would call her as often as I did, and I would call her every other day."

And why did Carol Channing make such efforts on behalf of Barbara Walters's sister? "Because she has a great and good heart,',' Walters says firmly. "She got nothing from me; I have never interviewed her on a special or for 20/20. It has never come up. The generosity of Carol Channing is beyond compare. I have never heard her say an unkind word."

Such testimonials abound among Carol's friends, who tend to be influential media types but who invariably insist that Carol's loyalty has nothing to do with their power. "People said to me, 'Charles Lowe will love you as long as you've got the column, but after that's gone, forget it—it's not your blue eyes that makes these people like you,' " reports Maxine Mesinger. When she and Carol first met, Mesinger worked for The Houston Press, but one day in 1964, "the Chronicle bought the Press and put it off the streets," she says.

Mesinger was visiting a sick friend in Memphis, but less than an hour after she learned that her newspaper had been closed, the telephone rang. "Charles had tracked me down to a hospital room in Memphis," Mesinger says, still amazed. "He said, 'You don't have to worry about a damn thing—you've got a job with Carol and me. Your son can stay in boarding school—don't worry.'" Unbeknownst to Charles, Mesinger had already been hired by the Chronicle, but she has always treasured his concern.

There is another side to Carol Channing, however—one that her influential friends may never see. Back in 1964, Willard Beckham lived in a small town in Oklahoma and was so obsessed with Carol Channing that his parents bought him a platinum wig so he could act out Hello, Dolly! in their living room. "I was a little fat kid with a buzz haircut, and I M didn't think about anything but Hello, Dolly!"

Beckham recalls. "I had this real fantasy that around the corner would come this big white Rolls-Royce, and inside would be Carol Channing, dripping with rhinestones, and I would run into her arms and never look back."

When Hello, Dolly! finally went on tour, Beckham's parents drove him the three hours to Oklahoma City and bought him a ticket. "I had every number memorized, and I wept from beginning to end," Beckham says. "It was the most magical theatrical experience of my life."

After it was over, he found his way backstage and knocked on Channing's dressing-room door. "Finally the door opens, and there stands Carol Channing. 'What do you want?' she said. I told her all about idolizing her, and how seeing the show was my lifelong dream, and I asked her for her autograph," Beckham reports. "She got this really sweet smile on her face, and she said, 'You want my autograph? You want my autograph?'" He mimics her cloyingly sweet, faux-humble tone.

"And then she screamed, 'Well, write me!' And she slammed the door in my face."

Beckham was devastated, but years later he landed a job in the chorus of Lorelei. "I thought this was the greatest thing in the world—I couldn't believe I was going to be working with Carol Channing!" he says. "She was fun, and a trouper to work with, but she was a major, major diva. There's the public persona, with that innocent façade, that 'How are you, darling?'—and then there's this really tough woman you see behind closed doors. You're terrified of her because you know what kind of power she has."

When Beckham joined Lorelei, things weren't going well. "They had been on the road a long time, and I came in on a wave of firings," Beckham recalls. "Carol and Charles would gang up with the producers to blame everyone else for why it wasn't working." They became increasingly incensed with the show's lyricists, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and one day a company member walked past Carol's dressing room while she was sounding off about Comden. "It wasn't too long after that that Comden and Green were out," says one company member.

Nor was Comden the only target of Carol's wrath. During the Los Angeles opening, something went wrong with Carol's microphone. She was livid. "That night, in her curtain speech after the show, she said, 'I have to apologize for our soundman. It's such a difficult job he has. He has to turn that little switch onnnnnnn, and he has to turn that little switch offfffff,'" Beckham reports. The audience laughed, but the soundman was enraged by Channing's public ridicule. "He quit," Beckham says. "He said, 'I'm going to shove it up your ass!' "

Continued on page 292

Continued from page 268

No matter what the circumstances, Channing's only concern seemed to be the show. "One night, during a preview in Boston, a glass panel fell out of the lighting booth onto the audience in the balcony, and some people got cut," Beckham says. "They were hauling them out. Carol was told we would have to hold the curtain, and her only comment was 'Thank God it's not opening night!' Not 'Oh, my God—was anyone hurt?' All she thinks about is business and the show."

Channing's single-mindedness extends even to her personal habits, which are famously peculiar. For many years she suffered from severe food allergies, which she blamed on the hair bleach she used for so long, and she was notorious for traveling with organically grown food in special silver containers; wherever she went, she had chemical-free food flown in, even taking her own meals to White House dinners. She was particularly noted for carrying around silver thermoses of bluefish.

These days, although her worst allergies have abated, her eating habits remain somewhat unusual. One night I watch in amazement as she orders the aide who travels with her to puree her entire dinner. It arrives as a carafe of viscous bilegreen liquid that Carol proceeds to drink with relish. But she must be doing something right; she stays up most of the night talking animatedly to me, and pops out of bed early the next morning. "She always calls and wakes me up," reports the show's press agent, who is less than half Carol's age.

After all, there's no time to waste; in every new town there are potential theatergoers to be wooed. And while some might find Channing's fierce determination chilling, theater people understand it perfectly. "It's just Carol fighting to preserve her career," Beckham observes. "It's what has made her survive."

"Yes, she's tough," admits Marge Champion, who discovered Channing in 1948 and brought the eccentric young comedienne to her husband, the late Gower Champion, who launched Channing's career by casting her in Lend an Ear and later became the original director of Hello, Dolly!

"You have to be tough," Marge Champion adds. "You can't withstand this business if you can't take the failures and down times, as well as sopping up the good times like a sponge. She is a classic case of the iron butterfly. If she didn't have that, she wouldn't be around."

Channing is sitting in the living room of her hotel suite, soaking her feet in a tub of vinegar and water. "It takes the sting out," she assures me. It's mid-afternoon on a sunny day, and she's wearing white short-shorts and a skimpy yellow halter with no bra underneath. It's an outfit I would have hesitated over at 20, let alone 74, but Channing's sense of personal style has always been a wonder. For decades she never permitted herself to be seen without a wig on her head; many of her friends simply assumed she was bald. Her family dutifully cooperated to protect her image when Carol wasn't ready for company. "Chan would get a paper bag for my head if the doorbell rang," Carol recalls fondly, as if this represented the height of filial devotion.

She was equally attached to her trademark false eyelashes. "I've worn them since I was a teenager," she says. "I never let anybody see me without them—ever! You can make your eyes as big as you want with false eyelashes."

But decades of living in eyelash glue finally irritated her eyelids to the point where even the cortisone cream she slathered on every day ceased to soothe them. It has done permanent damage to her vision, and all the years of yanking off false eyelashes had ripped out her real ones. "My eyelids are bald," she says sadly.

So she had to renounce false lashes. "I gave them up on February 22," she reports, as precise as a recovering alcoholic who can tell you the exact date of his last drink. She closes her eyes, remembering the trauma of it, and shudders. "I thought I was walking out onstage naked. I would dream that I had no clothes on. Look at me—I look like nothing!"

Actually, she looks quite nice.

Her face is pink and healthylooking, and her eyes appear normal, unlike those of the truly terrifying apparition I encountered backstage last night. Unable to give up the idea of big eyelashes, Carol now paints them on, an effect that is somewhat diluted when seen from several rows back in a theater, but that is enough to scare the horses when viewed up close. But without the grotesque makeup and the clownish smear of red lipstick she slashes across her face, Channing appears natural and quite youthful.

And things have been going remarkably well lately. "Carol said to me recently that the last year has been the happiest time of her life," says Barbara Walters, Hello, Dolly! is currently scheduled to open on October 19 for what is being billed as a limited engagement on Broadway. "Why are you calling it a limited engagement?" I ask Charles Lowe. "Because it sells more tickets," he replies with a grin. After New York, there are plans to take the show to England, China, and Japan. The Lowes can hardly wait. After a year on the road, another couple might be looking forward to going home, but the Lowes don't really have a home. They rent part of a house in Los Angeles, where they stash their things when Carol's not working, but that rarely happens. She's almost always working, even if the only gig she can get is "conducting" symphony orchestras with her familiar shtick.

What passes for home are the artifacts spread out around us. Although the Lowes have occupied this hotel room for only 24 hours, and will be leaving it in a few days, it is filled with a pleasant, homey clutter. Every surface is crowded with silverframed pictures: Carol with Walt Disney, Carol with Queen Elizabeth, Carol with Thornton Wilder, Carol with David Merrick. The hall table boasts a carefully arranged tableau of Carol's recordings, which range from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes to Winnie-the-Pooh, along with framed Hirschfeld caricatures and the treasured Mother's Day card from Chan.

My mission "My mission in life was to hide the fact that my mother was says crazy Channing.

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

"Instant home," Carol calls it; she takes this stuff everywhere, traveling from one town to another with 20 bags and trunks crammed with all her belongings, and each careful still life gets set up anew at every stop.

And after all, her real home is elsewhere. "She doesn't even like fancy dressing rooms," says Marge Champion. "She wants to not be comfortable in her dressing room; she wants to get out onstage. That's where she lives."

How long can she keep it up? Carol says she wants to drop in her tracks like David Burns, who died onstage in 1971 in 70, Girls, 70. "Mildred Natwick told me about it," Carol says excitedly. "He had a very big laugh; he delivered the line, and there was a laugh. And then Davey keeled over, and the laugh built. The audience didn't know there was anything wrong, you see. Davey didn't move; he died hearing the laugh build." She sighs blissfully. "I can't think of a better way to go."

But she's not planning to check out anytime soon. "How many women at 74 are triumphing in their careers and living the same schedule as a 26-year-old?" Susan Estrich points out. "How many women in their 70s are heading a large production of anything, let alone working seven days a week and filling the halls? I think she's a wonderful role model. What other woman can you name who's had a strong and happy marriage for 40 years, who has a good relationship with her son, and who continues to have her career? She's living her life to the fullest, enjoying the greatest high a Broadway star can have."

The week after I leave her, Carol is going to have a teeny-weeny operation on her eyes, in hopes of improving her vision. She brushes it off as if it were nothing; she'll be back onstage within a few days. "I don't have to see as long as they keep the lights bright and put fluorescent paint down so I can see the ramp," she insists.

Her vision may be impaired, but her eyes blaze. "I just need to see the lights," she says fiercely.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now