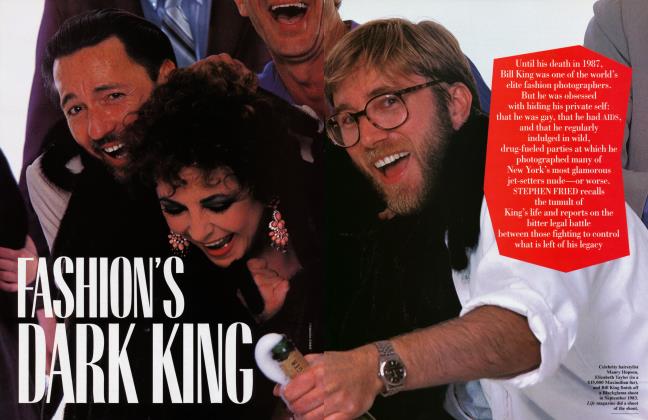

Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

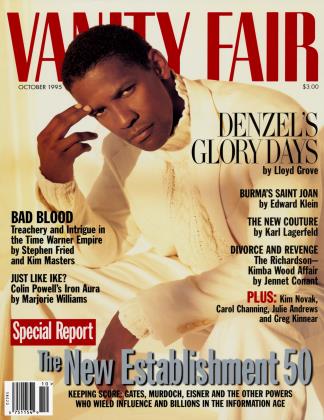

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE PRECARIOUS THRONE

The Media Business

Gerald Levin's $16-billion-a-year Time Warner empire is drowning in corporate debt, lawsuits, executive infighting, and wild takeover rumors

KIM MASTERS

STEPHEN FRIED

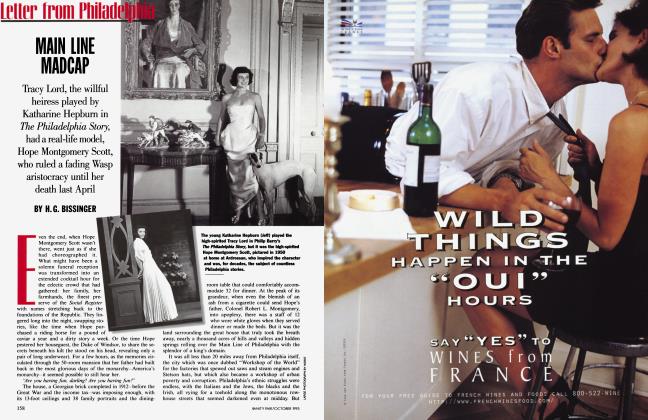

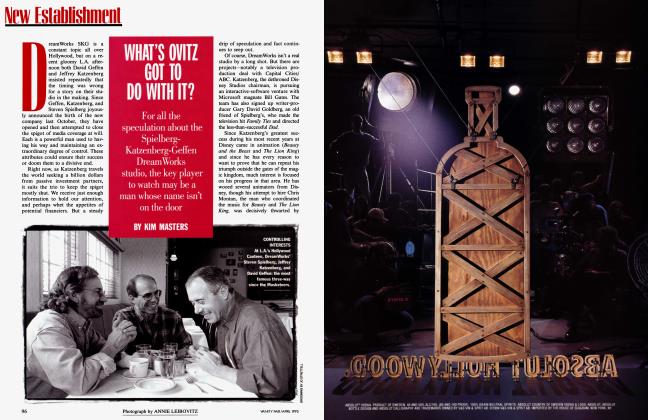

On a July day in Sun Valley, Idaho, the entertainment heavyweights of Time Warner gathered for a group photo. There was Michael Fuchs, the brash head of HBO, who had just added to his fiefdom the troubled Warner Music Group. There were Robert Daly and Terry Semel, who run the Warner studios—and who have fired occasional warning shots past Fuchs. And, of course, there was Gerald Levin, the uneasy caesar of the empire.

"It was one of those pictures against the pines and the blue, blue sky, smiling and happy," says an observer. As it was snapped, one mogul—David Geffen insists it wasn't him—turned to Herbert A. Allen, the host of the annual Sun Valley retreat of New Establishment powerhouses, and said he had to get a copy of that picture. With all the tensions at Time Warner, it could be historic. "You'll never be seeing this again," he said wryly.

It has reached the point where the top brass at Time Warner can't even get through a photo opportunity without people wondering what it means for Jerry Levin's future. "Somehow, we're sort of on the defensive," says company president Richard Parsons. "There is a presumption abroad in the land that if Time Warner is doing it, explain to me why it isn't wrong. That view is incorrect, and we have got to overcome it."

The view was not overcome during the talent portion of the retreat, when corporate chieftains get a chance to pitch their companies to a roomful of investors. The pageant began with Edgar Bronfman Jr., who only months before had been viewed as a starstruck showbusiness wannabe. Even though he didn't have a lot to work with—earnings in the spirits and beverage businesses were flat, and he had only just taken the helm of MCA—he charmed everyone.

The next day, the Time Warner team took the floor—with good news. It owned one of the leading studios in Hollywood, which was riding the wave of Batman Forever and The Bridges of Madison County (adapted from the best-seller published by its book division), and it was also a force in TV production, with the top new drama, ER, and comedy, Friends. It owned the world's dominant music company, which had just reported record earnings—again—and was off to another strong quarter with the chart success of Hootie & the Blowfish, the Batman sound track, John Michael Montgomery, Natalie Merchant, and Naughty by Nature. It published three of the four top magazines in the country—People, Sports Illustrated, and Time. It owned the country's pre-eminent pay-television service, HBO, and its cable company was the second-largest in the nation. And even though its stock had been lagging, the big Batman opening and the prospect of cable deregulation had recently shot Time Warner shares up more than 6 percent in one day.

Nevertheless, some in the audience were fretful about the turmoil in the company's record division, its heavy investments in cable, its bet on interactive television, and its $15 billion debt—which, according to industry analyst Harold Vogel, will cost Time Warner about $90,000 an hour in interest this year. There were also fears about the stability of the studio because of recurring rumors that Semel, Warner's chief Hollywood star schmoozer, would leave for MCA.

Levin led off, and though he is not a scintillating speaker, he turned in a pretty good performance. "He almost showed some warmth," says a member of the audience who knows and likes him. But his teammates came up uncharacteristically flat. Semel insisted on slogging through an uninteresting slide show. Fuchs, who can usually work a room like a stand-up comic, was faulted for making bad Bob Dole jokes instead of addressing the ongoing purge in the Music Group. (Only his date, skater Katarina Witt, and his orange jeans were noted in The Wall Street Journal.)

It was not what Levin had hoped for, especially since he was being upstaged by Bronfman—a new competitor who also happened to own nearly 15 percent of Time Warner's stock, a stake he could use as a weapon. "Here's Edgar, who gets up and brilliantly tells an uninteresting story but with great intelligence and humor and wit and self-deprecation," says Frank Biondi, the Viacom chief executive officer. "Then Time Warner gets up and has, I think, a pretty interesting story . . . but somehow they were able to make the story a little less interesting than it is."

"Time Warner has a pretty interesting story, but somehow they were able to make it a little less interesting than it is."

The chairman of another entertainment company has a harsher appraisal: "Some analysts walked away saying, 'Gee, Time Warner has a lot of great assets. Wouldn't it be great if they had strong leadership?' "

In the weeks following Sun Valley, there was a dramatic realignment of the stars in the media galaxy: Disney bought Capital Cities/ABC to become bigger than Time Warner and hired CAA's Mike Ovitz. Westinghouse tried to buy CBS, and then Ted Turner (in whose company Time Warner has a 17.4 percent stake) said he wanted a network, too. And the feeling on Wall Street and in Hollywood was that the action had to shift to Time Warner.

"Somebody will take a run at Time Warner," said one executive. "So long as people perceive Levin as weak, he is vulnerable."

A leading Wall Streeter concurred: "The wolves will be circling in time."

Since Jerry Levin took the company's helm in 1992, many have questioned whether he could hold together the marriage of inconvenience that is Time Warner. By some measures, the $16-billion-a-year media conglomerate is roaring along. But Time Warner persistently manages to be less than the sum of its parts. And after three years, Levin has yet to convince the world that the company's biggest problem isn't. . . Levin.

"He gets no credit for anything he's done successfully," says Geoff Holmes, Levin's former head of interactive television. "He's got every division of Time Warner reporting doubledigit record profits, and nobody could care less."

Levin has a vision of a company for the 21st century, offering services that the current generation may not understand but that three-year-olds who already know how to program a VCR will embrace. He sees a world in which Time Warner can muscle its way into the telephone business, sign up customers who want data transmitted over a cable modem at the speed of light, and be the first to offer everything from movies on demand to shopping and banking services on interactive television. He plans to own the pipeline—cable—and much of what gushes through it.

But Levin's vision worries people who think it would be safer to emphasize the movies, music, and magazines that built the empire. They also point out the dangers of mixing businesses which are not regulated by the government with cable, which is.

Levin doesn't sell his vision well, and he hates having to try. His intelligence and his command of detail are apparent. But he comes across as aloof and detached, displaying what one of his own executives describes as "a particular kind of arrogance."

Levin clearly enjoys the power and prerogatives of running one of the largest entertainment companies in the world. He reads and watches everything, sending notes and E-mail messages to editors about stories in the magazines or calling Steve Brill, his partner in Court TV, to ask about its trial coverage. He saw the new Julia Roberts movie, Something to Talk About, four times, and recently flew to Los Angeles to check progress on Space Jam, a Warner feature starring Michael Jordan. (He was disappointed, after packing his tennis shoes, that he didn't get to play with Jordan on the N.B.A.-class court that Warner's had built for the Chicago Bulls star.)

But some feel that Levin's pleasures are diminishing. Despite his rather ascetic image, he used to have two houses on Long Island and one in Santa Fe. All have been sold in favor of an apartment in Manhattan's River House—near the office. Associates say he works from early morning until late at night but seems more distant and unavailable than ever. A Time Warner insider says, "I've watched him just tighten up and tighten up until he squeaks when he walks."

Another source who knows Levin well says, "Jerry walks around carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders with a body language that is only comparable to Richard Nixon's. This is a guy who used to have fun. Now he takes himself so seriously. He is so cut off. I think he's numb."

At 56, Levin is stooped and graying. His eyes recede under a pair of bushy brows. His chin is not strong. A biblical-literature major at Haverford College, Levin has never lost the aura of an academician. He bears little outward resemblance to his late predecessor, the charming Steve Ross, whose generosity to others—and himself—was legendary. Ross created an artist-friendly corporation renowned for its extravagances. "Have you ever flown on one of the Warner jets?" one Hollywood agent asks. "Have you ever been in the Aspen house? I could co-opt you in 15 minutes if I started throwing the Warner's shit around."

Ross was indeed a tough act to follow. "If you were illustrating it with a cartoon, you'd have a tiny little Levin in these huge boots that would be labeled 'Steve Ross,' and he would be struggling to climb out," says a top executive at a rival company.

Levin, who rose from Time Inc.'s video division, has never forgotten the years of being regarded as "that guy Levin in the double-knit suits," whose presentations about new HBO subscribers in Wilkes-Barre caused "titters around the room." Those frustrating years ended when he made his name by pushing to have the fledgling service distributed by satellite—a development

that revolutionized the cable industry.

Even now, says a longtime acquaintance, Levin derives a measure of his identity from that episode. "He can say, 'I'm different. I'm more intellectual. I'm a long-range, visionary thinker.' "

Levin, according to a publishinggroup executive, was known' as "the business guy whom the edit side loved. He read books. He spoke in paragraphs."

"I will never forget my first meeting with Jerry," says Bridget Potter, a recently departed Home Box Office executive. "He had just taken his wife to Paris for her birthday for two days. I thought that that was the best. We spent the whole afternoon talking about television. He had such knowledge in his head about the minutiae of my world. And he had a manner which was so sophisticated and so open."

"I've watched Jerry Levin just tighten up and tighten up until he squeaks when he walks."

But many of Levin's colleagues started re-evaluating his character after watching him duel with another top Time executive, Nicholas Nicholas. The two became colleagues in the mid-70s, when Nicholas was brought in over Levin's head at HBO—and got credit for the resurrection of the service. But in 1980, Levin surprised the oddsmakers by beating out Nicholas for the top job at Time's video division. A few years later, however, Nicholas was slated to become Time's next C.E.O.

By then Levin had been involved in a number of losing propositions, including an infamous, costly deal to create TriStar Pictures. The deal imposed no caps on the amount HBO had to pay to run TriStar films. (In an extreme but important example, the company ultimately had to cough up $36 million for Ghostbusters.) Joseph Collins, who was then at HBO and is now chairman of Time Warner cable, still keeps a Stay Puft marshmallow doll in his office to remind him of the debacle. Frank Biondi, who was chief executive officer of HBO, lost his job; Michael Fuchs took his place. Levin survived and became Time's chief corporate strategist.

Nicholas's anointment was a heavy blow to Levin, and some expected Nicholas to dismiss his rival. By then, as Connie Bruck later reported in her Steve Ross biography, Master of the Game, Nicholas is said to have told the Time board that Levin was valuable but should never again be in a position of operating authority. But he kept Levin on and eventually named him vice-chairman of the company.

Feeling vulnerable to a takeover in the overheated climate of the 80s, Nicholas and Levin devised a "transforming transaction" that would guarantee Time's future: a merger with Warner Communications. Levin took a lead role in the negotiations, fighting to ensure that Nicholas would be designated Steve Ross's coequal and successor.

After working out a cozy, low-debt merger in 1989, Time and Warner found their deal undone when Paramount made a hostile bid for Time. The top executives at Time and Warner—all of whom stood to make a fantastic amount of money if the original deal went through— were in shock. The episode gave Levin an opportunity to shine.

"That's the first time I felt I could run the company," he says. "When the whole premise of your existence is at stake, it's a time for tough, clear thinking and acting, every hour of the day."

One insider downplays Levin's role. "It was not because he's a leader of men," he says. "But he was a master of detail. He's great at that stuff—the smartest kid in the class."

Instead of the merger they had envisioned, Time ended up buying Warner— with Warner shareholders reaping much of the benefit—and the new company took on a terrifying $16 billion in debt. Levin believes that some of his problems can be traced to Time shareholders who are still bitter about not getting a chance to consider Paramount's whopping $200-per-share bid. Time Warner's image on Wall Street has been "infected," he says, by the lingering resentment over the snubbed offer, Ross's lavish compensation, and his subsequent efforts to raise money from shareholders.

"We're eventually going to get on the other side of this," he says. "Eventually you have a new company that isn't like Time Inc. or Warner Communications. We're pretty close now." In the meantime, however, the buttoned-down Time people tend to regard their Warner colleagues as prima donnas who pocketed more money in the deal.

Continued on page 99

Continued from page 96

"Levin was left a financial pile of rubble. If Steve Ross had survived, he would have been flat bankrupt."

After the merger, Ross and Nicholas became co-chairmen, but their marriage quickly frayed. Nicholas thought Time Warner should sell about $5 billion worth of assets to pay down the debt. Ross favored reducing the debt through a series of "strategic alliances" with European and Asian partners. Levin sided with Ross.

But Ross circled the globe without securing the hoped-for partnerships. Finally he made deals that would come to haunt Levin: Time Warner split off its cable holdings, Home Box Office, and the Warner studios into a unit called Time Warner Entertainment. Two Japanese companies, Itochu and Toshiba, each put up $500 million for a combined 12.5 percent of T.W.E. Many analysts believed the strategic allies had paid too little to get a stake in some of the Time Warner crown jewels. And the debt still loomed large.

In embracing Ross's plan, Levin pitted himself against Nicholas and helped oust him. Levin took Nicholas's job and moved quickly to ensure that he would succeed the terminally ill Ross. Levin says that because he came from the video side of Time he was uniquely suited to the task of melding the companies. "I believe I'm the only one who could have done it," he says.

After Ross died, Levin sold another 25.5 percent of T.W.E. to US West, a regional telephone company. Now some think he is paying a price for pursuing Ross's strategy. "Jerry Levin was left a financial pile of rubble," says a Wall Street eminence. "The company from the outside has great assets. Steve Ross sold off a large portion of those assets for a farthing. If Steve had survived, he would have been flat bankrupt."

Despite the obvious differences, there are similarities between Ross and Levin. Ross was content to let his division chiefs go head-to-head with one another, and Levin says that he, too, believes that encouraging competition is the best way to exact a strong performance. "I really don't believe in synergy," Levin says. "I never mandated, ordered, gave medals for synergy."

[2 But Ross was better at navigating the 3 creative tension. "He did manage the p company in some ways not very differ§ ent than Jerry did—aloof and apart," says Robert Morgado, the recently ousted chairman of the Warner Music Group, who worked for both men. "But the difference between Steve and Jerry is that just when Steve sensed that something was about to explode he would smother it with affection and love."

Levin is more overtly autocratic. "He does not have a core group of counselors, advisers, around him," says a source who has worked with Levin. "Jerry keeps his own counsel. Jerry decides policy and comes in and announces it."

Time Warner board member Lawrence Buttenwieser says that the comparisons with Ross are unfair and that Levin deserves more recognition. "Just look at the position of the company in the business world today," he says. "If he's going to get criticized because something is wrong with the company, he should get credit because something is right with it."

What has Jerry Levin done right? Cable is controversial, but if you're a fan, he has certainly built up the division. He kept Michael Fuchs at HBO until both he and his pay-TV network matured and hit stride, with original programming such as The Larry Sanders Show and the film adaptation of And the Band Played On. He didn't meddle with Bob Daly, the steady, straitlaced leader who since the semi-retirement of MCA's Lew Wasserman has become Hollywood's most durable power, or with his co-chairman and likely successor, Terry Semel. But on occasion he has certainly annoyed them.

One of the divisions where Levin has had obvious positive impact is publishing. Some of his moves were controversial at the company—mostly because outsiders got jobs that insiders coveted—but so far those decisions have paid off. In 1992 he brought Don Logan from the company's Alabama-based publishing concern to consolidate the magazine and book businesses. And last fall he named former Wall Street Journal editor Norman Pearlstine editor in chief of Time Warner.

Logan moved quickly to gut a disastrous plan that centralized the sales of advertising in all the magazines. He also imposed a series of cost-cutting measures that made editorial employees wonder if he realized how grueling putting out weekly magazines can be. But he has also encouraged the magazines to be more entrepreneurial: now each publication can try to spawn its own ancillary products, such as People's new In Style and Sports Illustrated's children's magazine and regional football annuals. And even in the face of stiff price increases in newsprint, he has been patient with Entertainment Weekly, which still bleeds money, Time, which is struggling to reinvent itself, and Life, which is battling just to stay alive.

In February, Pearlstine instigated enormous changes on the editorial staff at Fortune. He also tried to get the extremely lucrative People magazine some respect, calling it the best-reported publication in the company. Despite the praise, he caused some ripples in a meeting with senior People editors by suggesting that they might be spreading themselves too thin with special issues and ancillaries: some thought he was hinting that a major overhaul was in store. He says that is not true. In fact, it now seems more likely that Money magazine, whose newsstand sales are flagging, will be next on the retooling list.

A lot of attention has focused on the top editorial job at the group's secondlargest title, Sports Illustrated. Several editors are being given a chance to run the magazine for 12 weeks at a time. Bill Colson, one of the magazine's assistant managing editors, finished his heat in July. Now Life magazine's Dan Okrent is having his chance, possibly to be followed by a third, unnamed candidate. The competition has been dubbed Pearlstine's "Bake-Off."

Although Logan supports Pearlstine's decision to fill the S.I. post this way, he generally feels that Time Warner allows too many of its top jobs to be filled by public horse race. But if it made surprise announcements like everyone else, Time Warner might lose its position as, if not the biggest, then arguably the most entertaining of the major entertainment conglomerates.

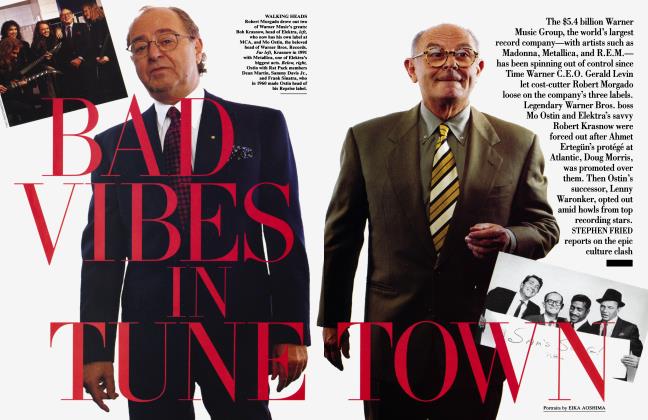

Even in a company of outsize dramas, nothing has matched the guerrilla theater at the music division. It has become a case study of Levin's shortcomings in dealing with crisis and the fractious personalities within his corporation. The Warner Music Group is the world's largest record company, driven to nearly $4 billion a year in revenue by the domestic Atlantic, Warner Bros., and Elektra/EastWest labels and strong publishing, manufacturing, and international operations. It has been through self-inflicted hell.

The battle over the division began in earnest in 1993. That's when Music Group head Bob Morgado—the former aide to New York governor Hugh Carey—was given the green light by Levin to impose his "strategic plan" on Mo Ostin, the 68-year-old patriarch of Warner Bros. Records. When Ostin, who for decades had enjoyed the privileged position of reporting directly to the chairman of the parent company, was forced to report to Morgado, the fight was on between the New York corporate "suit" and the Los Angeles-based record executive known for his blazers and open-collar shirts.

Two of the top gangsta-rap artists, Tupac Shakur and Dr. Dre, were in jail, and a third,

Snoop Doggy Dogg, was facing a murder charge.

Industry-watchers still debate whether the Music Group actually had any major management problems or whether Morgado created some to justify his power play. Levin was warned by artists, business associates, even competitors about the possible consequences of attacking Ostin. But he accepted Morgado's view that the companies were not maximizing their profits.

"The fact that the record industry was such a cash cow was in the closet," says one Music Group executive. "When they realized we're such big spitters of cash, they started saying, 'If these idiots can do this, what if we ran it, you know— what if we got some smart people in there?'"

By the summer of 1994, the power struggle between Morgado and Ostin had transformed the world's most stable record company into a combat zone. In July, Morgado created a new job for Atlantic Records co-chairman Doug Morris, the well-liked former songwriter who had been a protege of the label's cofounder Ahmet Ertegun. Steve Ross had wanted Morris fired, but with Morgado's support he had surprised the music world by resurrecting the moribund Atlantic label. Morris was promoted to chief of all the U.S. labels—including Warner's—in a move that both men would eventually regret.

One of Morgado's closest advisers warned him about promoting Morris. When Music Group general counsel Fred Wistow was told of the plan to elevate the Atlantic chief, he scribbled something on a piece of paper and handed it to Morgado. It was one word: "Frankenstein."

After Morris's appointment, Elektra chief Bob Krasnow left immediately, For Ostin, Morgado's decision to elevate Morris without clearing it with him first was the last straw, leading to his announcement several weeks later that he would quit when his contract expired in December. His protege, Lenny Waronker, accepted, and then quickly turned down, the chance to succeed him. That left the roster of powerful Warner artists—including R.E.M., Madonna, Neil Young, Green Day, and k. d. lang— in a state of dismay and confusion. And then Morgado and Morris—who had been skirmishing over how absolute Morris's authority on domestic matters was— went to war over who had the power to name Ostin's successor.

As the acrimony between them peaked, Morris briefly considered going back to Atlantic, which Morgado told him he could do, at the same time offering Ostin's job to the head of Warner U.K. Several hours later, Morris changed his mind and decided he wanted to oversee all the U.S. labels after all. The next morning, 12 of the company's top music executives threatened to take action together if Morris did not prevail.

Levin was unwilling to call the group's bluff. One former Time Warner official reveals that Levin feared more than just a mass exodus: the C.E.O. had received word that, if necessary, the group would attempt to enlist the support of Edgar Bronfman Jr., Time Warner's single largest shareholder, against him.

Morris and his troops were victorious; Morris was given a new title and a better contract. At the end of October, Morris gave Ostin's job to Danny Goldberg, the former artists' manager who had replaced him at Atlantic and become his strategist.

Although Morgado had lost a major battle, he was led to believe he could still win the war. But, for the moment, Levin hung Morgado out to dry in the media. Reporters were getting so much inside information that it seemed as if Time Warner's E-mail were being offered as an on-line service.

Just before Christmas, Ostin stepped down. His exit produced the kind of drama rarely seen in corporate America: employees openly weeping over the fate of their boss. As Ostin descended the steps of the Warner Bros. Records building in Burbank with his wife, Evelyn, he was cheered by hundreds of emotionracked staffers wearing red and blue

company caps.

The scene was videotaped, and a sound track was added: "The Best Is Yet to Come" sung by Frank

Sinatra. The tune's sentiments were appropriate: Ostin was about to be courted by all of Time Warner's competitors. But at the Warner Music Group, all anyone could hope for was that the worst was over. It wasn't.

As 1995 began, Morgado and Morris publicly pretended that peace had broken out. But the situation hadn't improved; the two fought about everything. Morgado's perception was that he was fighting more than one man: he believed Danny Goldberg was willing to play out almost any battle in the press. While Morgado viewed Morris as "insecure," he saw Goldberg as "evil. And he preyed on Doug's insecurity." (Although Morris declined to comment for this story and Goldberg did not return several phone calls, both are known to believe that the problems in the Music Group stem from Morgado's inability to delegate power.)

In late January, tensions mounted when The Wall Street Journal learned about a scandal that had been brewing within Atlantic Records. It involved tens of thousands of promotional CDs the company says were routinely being sold under the table to retailers and distributors by its own sales executives. At the time, the acrimony was over who leaked the story of the internal investigation, which Morris had started in October. But in subsequent litigation the chronology of events would become an issue. Morgado says he was not informed about the investigation until after Morris signed his new contract in early December—which Morgado feels was "unconscionable." Mel Lewinter, the recently ousted Warner U.S. executive and one of Morris's closest associates, says the investigation was discussed with Morgado in November. All agree the matter was turned over to corporate before year's end, and the company says 10 executives were eventually fired. (The lawyer for one says his client made no personal profit on the CDs, which were regularly given to stores in exchange for improved product placement.)

"I won't have my picture taken with Morgado," said Danny Goldberg. Asked why not, he replied, "It's out of respect for Mo."

The problems between Morgado and his record executives soon hit new lows. At the Warner Music Grammy party in L.A. on March 1, for example, Goldberg refused to have his picture taken with Levin and country artist Faith Hill because Morgado was in the shot. "I won't have my picture taken with Morgado," he said. When asked why not, he replied, "It's out of respect for Mo."

In the meantime, Morris was laboring to stabilize the labels he finally controlled. Each label had a deal the company couldn't afford not to make. Warner's had to re-sign Neil Young to Reprise. Elektra/EastWest had to settle its litigation with its biggest act, Metallica. And Atlantic had to finish buying another chunk of one of its major profit centers, Interscope Records, which owed a great part of its success to hard-core gangsta rap and the label's seminal rockers, Nine Inch Nails. (Apparently no one was worried that two of the top gangsta-rap artists under the Interscope umbrella, Tupac Shakur and Dr. Dre, were in jail, and a third, Snoop Doggy Dogg, was facing a murder charge.)

All three deals got made, but critics claimed that Morris was overpaying. Sources close to Neil Young say his new, $25 million deal includes what amounts to a $5 million signing bonus and a per-album guarantee of nearly twice the $2 to $3 million that Young was ready to accept before Ostin's ouster. Many Warner executives were also given new, bigger contracts to keep them from leaving. "They've now got five guys doing Mo's job," quipped an insider.

Even though the Music Group was about to announce record profits, it again became an emergency for Levin when Morris and Goldberg asked to see him about more problems with their boss. This time the anti-Morgado message was being paired with the notion that Mo Ostin might bring his new label to Time Warner—something Levin had urged Ostin to consider when Morgado was leaning on him.

Several people had something to gain by convincing Levin that Mo would come back. Ostin agreed to talk to Levin about the possibility—in a secret Acapulco meeting—but only if Warner's freed him to discuss label deals with others. Goldberg was playing the Mo card to get Morgado: he told Levin that the only way Ostin would consider coming back was if his nemesis was fired. The message was reinforced by David Geffen, who said he expected Ostin to join the DreamWorks team. If that happened, Geffen said, DreamWorks could never ally itself with Time Warner as long as Morgado was in charge of music.

In mid-April, Levin told Fuchs that he would be replacing Morgado and adding the music division to his HBO responsibilities. Fuchs, the most outspoken and openly ambitious division chief at Time Warner, had not made a grab for the music job, but it was no secret that he was hungering for a new challenge after 19 years at HBO. He had supported Levin's advance to the top job and was patiently awaiting his reward. "This decision had as much to do with Jerry trying to take care of his problems with Fuchs as it did with [the Morgado situation]," says one entertainment executive.

The record company would keep Fuchs busy without giving him authority over Bob Daly and Terry Semel. While the studio co-chairmen say they've made peace with Fuchs, they had long quarreled with him over HBO's payments for Warner movies and Fuchs's decision to invest in Savoy Pictures, which Daly saw as a competitor. But though Fuchs had risen from running the company's smallest entertainment division to effectively overseeing more company revenue than any other division head, he still did not directly impinge on Daly and Semel's turf. "I understand why Levin did it," says a prominent industry executive. "If you think Bob and Terry were pissed when Fuchs was given the Music Group, imagine what it would have been like if they were reporting to him!"

Perhaps it was just as well for Levin to keep Fuchs busy, since many believe that he has an appetite for Levin's job. "He gave him the job to shut him up," says one source. "I know what Michael is trying to do: he's trying to run Time Warner. He's trying to be Jerry Levin. And he wanted Wall Street to see him as Steve Ross." Fuchs dismisses the idea that he is angling for more—at least in the immediate future. "I have enough on my plate right now," he says.

Morgado was fired on May 2, a move that many saw as coming far too late. Industry-watchers took the dismissal as a tacit admission that Time Warner had made key errors with the Music Group —although Levin himself has maintained a stubborn silence on this subject.

But Fuchs quickly developed a new sympathy for what Morgado had experienced. "The perception was that what went on was Robin Hood and his merry band scaling the walls of the castle to get at the Sheriff of Nottingham," Fuchs says. "Now that I've been in the castle, I can tell you that the original story was not so accurate—even though there was a premeditated, almost obsessional campaign to create that impression."

Fuchs was known to run HBO so tightly that one Music Group executive worried he would treat them "like a bunch of gerbis."

Fuchs is not one to be a figureheadin fact, he was known to run HBO so tightly that one music executive worried he would treat them "like a bunch of gerbils." But when it came to the American labels, it would have been difficult for Fuchs to be anything more than a figurehead. Morris had negotiated such a good deal that his authority was almost absolute. If the two were going to have a working relationship, Morris would have to voluntarily give back some of the power he had won to protect himself from Morgado. In return, Fuchs was willing to let Morris run the record business worldwide.

In this delicate process, Fuchs appears to have made the first formal offer by giving Morris a letter promising to promote him to the international job within six weeks—or face a breach of Morris's contract, which might trigger a $50 million payout. Morris said he was willing to concede some of his contract clauses, but wanted to wait six months to see how everyone got along. Panicky about what Fuchs would do, Danny Goldberg came back from L.A. to keep close tabs on the situation.

Only weeks after Fuchs was appointed, the old rap-lyric issue, which had rocked the company during the 1992 controversy over Ice-T, reappeared in new packaging. Former secretary of education William Bennett and his conservative advocacy group, Empower America, joined with C. DeLores Tucker, chairwoman of the National Political Congress of Black Women, to denounce Time Warner—singling out Interscope. Their campaign was soon joined by another strong voice. "You have sold your souls," intoned Senator Bob Dole, priming himself for a presidential run. "But must you debase our nation and threaten our children as well?"

Time Warner and the Music Group now had to speak with one voice. Fuchs was chosen to be that voice—a problem for Danny Goldberg, who had been a major player in the American Civil Liberties Union. Goldberg gave an interview to The Washington Post which incensed Fuchs, and accepted an invitation to appear on Face the Nation which the company had already officially turned down. When Fuchs found out, he forced Goldberg to cancel, but the damage was done—the national audience was informed that Goldberg pulled out.

Despite these frictions—driven by rumors bouncing between the two camps—it was well known that Fuchs still planned to promote Morris to the international job. That's why the music world was so stunned on June 21 when word spread that Fuchs had fired Doug Morris in the coldest way possible. Morris was summoned from his office in 75 Rockefeller Plaza to Fuchs's office in the postmodern HBO building, ostensibly to finalize the details of his promotion. When he arrived, Fuchs presented him with a press release, which Morris initially thought was the announcement of his new job.

Morris quickly found out that the platinum handshake that he had watched so many other Time Warner executives get was being denied him. Bob Krasnow had received $7 million when he was pushed out at Elektra. And Bob Morgado was getting close to $60 million, no questions asked. But Morris learned that he was being fired "for cause." When he filed suit to challenge the dismissal, Time Warner roared back: the company wanted all the money that it had paid Morris in the past year, and even made his contract public. It revealed that he had (Continued from page 106) already been paid about $10 million in 1995—including salary, signing bonus, and his 1994 bonus.

Continued on page 115

(Continued from page 106)

In preliminary court papers, the company has said Morris was fired for not telling the company about the promotional-CD investigation before he signed his new contract. If Time Warner intends to pursue this approach, it could be a dangerous game. No music company has ever stood to benefit from close public scrutiny of its sales practices. "They gave everybody a turkey and then they ran out of turkeys, right?" asks one Music Group executive. "It feels creepy that they have to go after Morris personally."

While people usually associate this kind of hardball with Michael Fuchs, Levin has made it clear that he was in charge. The day after Morris's firing, Levin had one of his periodic lunches with the managing editors of all the major Time Warner magazines. "Levin said Morris and his colleagues were trying to destabilize the company," recalls a publishing-division source. "He said they were trying to get him out and were in the process of a coup. This could not be tolerated, and Fuchs had fired Morris with his complete support." When asked about the fate of other key Music Group executives, Levin said, "Once you cut the head off, you see how the body behaves."

According to the source, several of the editors agreed that they had never heard Levin talk that way before. "He was like Michael Corleone at the end of Godfather Ilf the source recalls. "The same cold, slit eyes. The same 'If you fuck with me, you die.'"

Fuchs moved quickly to remove Morris loyalists. He fired Mel Lewinter "for cause"; Lewinter is also suing, and Time Warner settled with the most prominent of the fired sales executives, fortifying its position on the CD scandal. Fuchs negotiated a departure settlement with Danny Goldberg, who will reportedly get about $5 million. And as Mo Ostin and Lenny Waronker tried to complete their deal to run the DreamWorks labels, Fuchs named the fourth chairman of Warner Bros. Records in less than a year. He chose Warner family favorite Russ Thyret, the burly, bearded, eccentric top executive who gave the most impassioned speech at Mo Ostin's going-away party. One former Music Group executive says, "He's gj the greatest noncommissioned officer of § all time. Can he become a four-star z general? I'm going to put my money on § him."

Some still wonder what to think about the year of living dangerously at the Warner Music Group. Was it the series of bad judgment calls? Or did Levin have some master plan to wipe out a group of talented executives who couldn't stop comparing him with Steve Ross?

"I lay this at Jerry's feet," says one disgusted former Warner Music executive. "He turned his back on Mo and Bob Morgado and Doug Morris. What does that say about this man? He's either completely immoral, completely unfeeling or unknowing, or this man has had this long-term agenda since he took over. Either way, here's a guy with one hell of a problem."

The competition to fill the top editorial job atSports Illustrated has been dubbed Pearistine's "Bake-Off."

Some Time Warner shareholders have made it clear that the music division is the equivalent of Bosnia: they may be willing to wring their hands over the conflict there without taking action. But if the trouble spreads—if Daly or Semel were to pull out at the Warner studios—they might be inclined to declare war on Levin.

The shareholders' major complaint is that they don't like the emphasis on cable or the lingering $15 billion debt. The debt has been a drag on the stock and, despite record operating income in all divisions, Time Warner has yet to turn a profit since the merger. The stock has risen from its most recent low of $31.50 to a recent high in the mid-40s, but needs to get closer to $50 to keep investors from feeling that the company is undervalued.

In February, under tremendous pressure, Levin pledged to reduce the debt. He announced that it was time to dismantle Time Warner Entertainment— the subsidiary consisting of the cable holdings, the studio, and HBO. The move could be interpreted as nothing less than a redefinition of the company's identity, a return to emphasizing its role as a supplier of "content"—movies, music, and magazines.

"I think the marketplace and his own warlords have told him they don't want to bet the farm on his vision," one of Time Warner's institutional shareholders explains. "He recognized if he's wrong, he's dead, and even if he's right, he may not have a job in six months, because he keeps fighting everyone."

Levin's plan—warmly received by major shareholders—was to regroup the cable holdings into a new, separate subsidiary. Time Warner would own a percentage of that company and load as much as half of its debt

onto it. According to Levin, this would still keep Time Warner on the cutH ting edge of ■ technology. Meanwhile, US West, V in theory, would [ trade its percentI age of the film studio and HBO for a stake in the new cable company. The Japanese partners, Toshiba and Itochu, would swap their interest for Time Warner common stock. Once again, the studio and pay-television service would belong, 100 percent, to Time Warner. Order would be restored to the kingdom.

Levin asserted that this solution would please everyone. "It's possible to have a structure which is satisfactory to those who do believe in the [cable] business, and those who don't, and those who can't make up their minds," he said.

The only hitch was getting US West and the Japanese partners to agree to the deal. Which raised the question: Why should they?

US West chairman Richard McCormick says that his company is willing to negotiate with Time Warner, but that he is "real happy" with the current arrangement. "There isn't any pressure on us to change," he says. At press time, a source close to Levin said Time Warner was planning to announce that the Itochu piece of the restructuring was completed; the Toshiba piece was nearly done. But an insider says he doubts that McCormick, who controls twice as much of T.W.E. as the Japanese partners combined, will agree to Levin's plan. "He's just stringing Jerry out," he says. "Every time Jerry goes to him with a deal, he just says no."

Critics say Levin has put himself at a disadvantage by announcing his plan. Some find Levin's tactics in this instance to be part of a disconcerting pattern. "If he thinks it, he says it," says one Time Warner executive. "I don't know of anyone except Jerry who would go to the press and say, 'I want to restructure and I want to do a deal with US West.' Everybody knows he just lost all his leverage. It's not so much his choices—he just telegraphs them too much."

Richard Parsons, the company president, contends that the partnership between Time Warner and US West is too important for either to engage in brinkmanship. "You can't afford to screw around with it by saying, 'Leverage, leverage, who has the leverage?' I reject the notion that we gave up our sneak-upon-'em-and-bag-'em strategy," he says.

Levin now says the US West deal is not the "be-all and end-all." He promised a restructuring, he says, but he didn't outline specifics.

And Parsons downplays the idea that Levin must now deliver on the restructuring within 12 to 18 months, as Levin said he would. "If instead of 12 to 18 months, it takes 24 months," says Parsons, "you don't get shot."

The restructuring wouldn't be so pressing if Levin had better luck selling his vision. But there is a growing perception that the company's grand experiment with interactive television in Orlando is failing. Perhaps one day customers will be banking, shopping, and ordering movies on demand through the Full Service Network. But it will take a lot of time and money to get there.

The Full Service Network is not the only technology that Levin has up his sleeve. But these new ideas, while they could pay off spectacularly, have a way of making Wall Street nervous. "Three years from now, you could wake up and find that you could get MTV from wireless cable, cable TV, the telephone company, or three satellite companies," says one major shareholder. "Why do you want to fight in that catfight when the clear beneficiary is the guy who owns programming? There are a lot of people in the company, including the studio guys and Michael Fuchs, who think it's a big mistake."

One associate believes that Levin is yearning for the glory days, when he was the boy genius who put HBO on satellite. "I saw Jerry saying, 'Full Service Network, this is my satellite again.'" In fact, Levin does analogize the two situations. And he discusses his conviction that his approach will work with a special fervor. "Somebody who scores gets in a zone," he says. "They have a mental picture of scoring a basket and they do it. The end point to me is video that you can manipulate on demand. I'm not staking the company on the Full Service Network, but I do believe in it strongly."

Back in October 1993, Levin said the company would hook up 4,000 customers to its Full Service Network by the following spring and link up all its systems within five years. The company was investing a reported $5 billion in the effort. "I've staked my career on it," Levin said stoutly.

"I know what Michael Fuchs is trying to do. He's trying to run Time Warner, to be Jerry Levin."

Finally, in December 1994—eight months late—Levin brought off an impressive presentation of the system. The only problem was that Time Warner wasn't ready to hook up the promised 4,000 customers—or even 400. The real number was closer to four. The Full Service Network was nowhere near ready.

"The news of its demise is untrue," says Joseph Collins, head of the cable division. But he casts Orlando as an experiment rather than a prototype. He acknowledges that the company has yet to figure out whether the system could even make enough money to justify the enormous cost of hooking it up. "It's very hard," he says. "This is an enormous software project. . . . We're going to know during '96 what the answers are to all those questions."

Meanwhile, even Levin's allies concede that he may have spooked his public by pressing so hard. "Jerry has seen the future and he's developed a strategy for achieving that future," says Parsons. "But we may have tried to go a little too fast, if not too far."

Levin's supporters say his main problem is that he's a bad salesman. Not that he hasn't tried. In December, he paid a visit to Edgar Bronfman pere et fils, Time Warner's largest shareholders, who had previously received very cool treatment from the company. Levin dispatched Richard Parsons to lunch with Courtney Ross, the widow of the patriarch—whose affection for Levin was so slight that she had balked at inviting him to her husband's funeral. Levin met informally with Toni Ross, Steve's daughter from a previous marriage. He started reaching out to institutional shareholders, such as Gordon Crawford of the Capital Group.

Levin doesn't view any of these moves as a change in strategy. He says he has consistently communicated well with people who matter, inside and outside the company.

Morgado feels Levin's strategy to communicate only when it's necessary is arguably a good one. But, he says, Levin stumbles because he finds even occasional communication an irksome chore. "He resents the intrusive quality of it," he says. Morgado has told senior executives that Levin must reprogram himself. "Jerry's reluctance to be a spear-carrier in a consistent and formidable way," Morgado has said, "is a problem."

In recent months, Jerry Levin has won some time. The prospect of deregulation and the restructuring plan have the stock ticking upward. (Recently the stock rose for less desirable reasons—rumors that G.E. might make a takeover bid.) Analysts have started to warm to the company again. "The sky has cleared," says institutional investor Larry Haverty, who was publicly demanding action from Levin a few months ago. "People are beginning to see that Jerry's strategy was the right strategy," says Parsons.

There are several land mines that Levin still must avoid. The biggest is Edgar Bronfman Jr., with his large stake in the company. Levin may now have reason to repent his unfriendliness when the Bronfmans appeared on the scene. But he has no regrets. He was angered that Bronfman didn't announce his intention to accumulate a major stake in the company. "You don't start a relationship that way," he says. He adds that Bronfman could never articulate where he thought the company should go. "It was like asking Ted Kennedy why he wanted to be president."

If Bronfman allied himself with another attacker, Levin would be vulnerable. And he is susceptible to other disasters. He has provoked studio cochairmen Bob Daly and Terry Semel, perhaps inadvertently, even though sources close to the situation agree that Levin views it as imperative to his well-being to keep Daly and Semel in place. "In his mind, he cannot have a mutinous Bob Daly or Terry Semel," says a top executive at the company. "He perceives he can't lose them. Right now, they may have the most leverage of anybody at the company leverage beyond the profitability of their division."

"They gave everybody a turkey and then they ran out of turkeys, right? It feels creepy that they have to go after Morris personally."

Levin irked Daly last year when he looked into buying NBC while the studio was launching its own television network. Daly also regards the treatment of Mo Ostin as one of Time Warner's signal mistakes. Daly and Semel are also still perceived to be cool to Michael Fuchs. Daly acknowledges he has clashed with Fuchs, but says, "We resolved our differences. . . . We may not be going to dinner a lot, because we have different styles. But he's a good executive and a good choice to run the Music Group."

As for Levin, Daly and Semel offer somewhat backhanded praise: "Jerry Levin has been totally supportive,"

Semel says. "He has allowed us to run our own shop and allowed us to do good work. The results speak for themselves. Why change what isn't broken?"

Daly says he plans to stay put "as long as I get up in the morning and I love coming to work." Semel also says he'll stay, but ever since Bronfman's purchase of MCA, Hollywood has buzzed with rumors that Semel might take a job there. (The buzz was not diminished in August when Semel joined MCA's new president, Ron Meyer, for a Mediterranean yacht cruise with Sylvester Stallone and producer Joel Silver.) Time Warner executives deny a rumor that Semel has an option to get out of his contract at the end of the year. But several sources say that the Warnerstudios co-chairman has already asked permission to negotiate with MCA—and has even met with Edgar Bronfman. If Semel jumped, he would join several other Time Warner executives, since Bronfman inherited Bob Krasnow's new label and gave Doug Morris one of his own.

While Fuchs has begun to stabilize the Music Group, hardly a week goes by without another emergency. The lawsuits with Morris and Lewinter could be quietly settled, but they might also be a time bomb. The situation with Interscope and gangsta rap has already blown up. Negotiations to sell Time Warner's 50 percent stake in Interscope back to the label seemed to be going smoothly until mid-August, when Interscope filed a suit against C. DeLores Tucker, accusing her of trying to interfere with the label's profitable distribution deal with Death Row Records. Two days later, Death Row filed a provocative action against Tucker, Time Warner, Levin, and Fuchs, charging them with violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO). Both suits allege that Tucker claimed to have an arrangement with Fuchs to offer Death Row an $80 million advance if it would make a deal directly with Time Warner and agree to stop making "misogynist, obscene, and pornographic music." Both Tucker and Time Warner say the suits are without merit, although there was clearly a botched attempt to get the labels to agree to a new lyrics policy. However the Interscope situation is settled, Fuchs is expected to announce such a policy, which will likely cause more controversy.

Music people are also paying close attention to the fates of two Warner Bros, artists. R.E.M., the label's most important band, is about to deliver the last album on its contract. If Fuchs and Thyret can't get R.E.M. re-signed, it won't bode well.

K. d. lang has a record due out October 10, making her one of the first major experiments in whether the Warner machine has been damaged. Lang's manager is cautiously optimistic, but some doubt that morale can be turned around so quickly. "Anybody who puts a record out here right now is a fool," says a source close to the company. "It's not fair to these artists to be in the middle of a fucking blender like this."

With this panoply of problems, some shareholders believe Levin is still in trouble. "Every indication I get is that the restructuring is not going well," says one. "The clock is ticking. His lieutenants are after him." The question is: Can Levin define himself as a leader in time? Can he persuade enough people to follow him into battle even when the company is battered by the controversies that will inevitably arise?

"Nobody's a natural-born C.E.O.," Parsons says. "Everybody goes through a learning phase when they get there. I have complete confidence in Jerry."

"Jerry's a smart guy," says Morgado. "If redemption requires him to come out of the shell and assume the mantle of the great communicator, I think he's capable of doing it. Intellectually, he understands it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now