Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

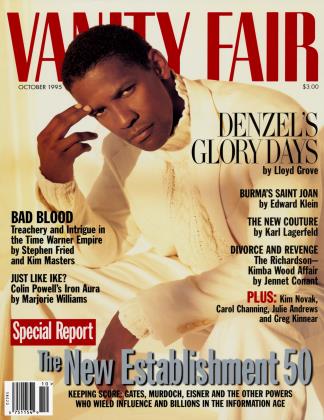

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMAIN LINE MADCAP

Letter from Philadelpia

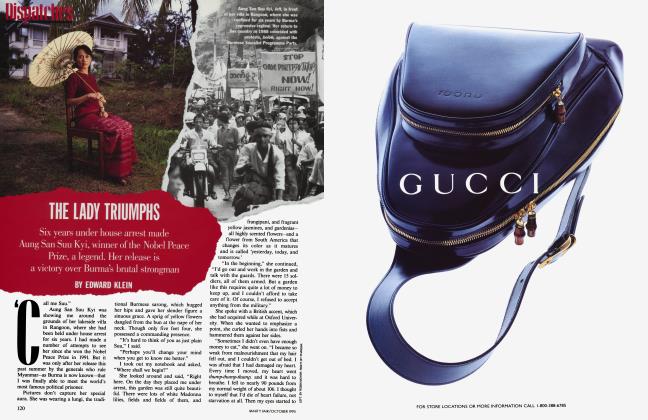

Tracy Lord, the willful heiress played by Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story, had a real-life model, Hope Montgomery Scott, who ruled a fading Wasp aristocracy until her death last April

H.G. BISSINGER

Even the end, when Hope Montgomery Scott wasn't there, went just as if she had choreographed it.

What might have been a solemn funeral reception was transformed into an extended cocktail hour for the eclectic crowd that had gathered: her family, her farmhands, the finest preserve of the Social Register with names stretching back to the foundations of the Republic. They lingered long into the night, swapping stories, like the time when Hope purchased a riding horse for a pound of caviar a year and a dirty story a week. Or the time Hope pestered her houseguest, the Duke of Windsor, to share the secrets beneath his kilt (he stood on his head, revealing only a pair of long underwear). For a few hours, as the memories circulated through the 50-room mansion that her father had built back in the most glorious days of the monarchy—America's monarchy—it seemed possible to still hear her.

"Are you having fun, darling? Are you having fun?"

The house, a Georgian brick completed in 1912—before the Great War and the income tax—was imposing enough, with its 13-foot ceilings and 38 family portraits and the diningroom table that could comfortably accommodate 32 for dinner. At the peak of its grandeur, when even the blemish of an ash from a cigarette could send Hope's father, Colonel Robert L. Montgomery, into apoplexy, there was a staff of 12 who wore white gloves when they served dinner or made the beds. But it was the land surrounding the great house that truly took the breath away, nearly a thousand acres of hills and valleys and hidden springs rolling over the Main Line of Philadelphia with the splendor of a king's domain.

It was all less than 20 miles away from Philadelphia itself, the city which was once dubbed "Workshop of the World" for the factories that spewed out saws and steam engines and Stetson hats, but which also became a workshop of urban poverty and corruption. Philadelphia's ethnic struggles were endless, with the Italians and the Jews, the blacks and the Irish, all vying for a toehold along the monotonous rowhouse streets that seemed darkened even at midday. But along the Main Line, where a boy could ride a pony from one grand estate to another, it was hard to imagine how any of the dirty struggles of the conflicted metropolis could blight the pleasures of a summer day. Or a spring evening. Or a cocktail hour.

"This is the only thing big enough to write my love on," wrote Edgar in 1931, using a piece of cardboard. "I adore you, o my baby."

It was here, in this house and on this land called Ardrossan—after a coastal town in Scotland—where Hope somersaulted, much to the mortification of the governess, from one end of the museum-like hallway to the other; here where Hope's debut was celebrated with a coming-out party where the Colonel greeted guests in a hunter's pink coat and silk top hat and proceeded to lead guests on a three-and-a-half-mile point-topoint race on horseback. "Never in the annals of society in this city has a debutante been honored in such an unusual way or been the recipient of so much social attention," wrote the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. Given the Philadelphia of the 1920s, where the annals of society were as scrupulously attended to as an English garden, where the aristocracy was the closest approximation of monarchy that America has ever been able to claim, it was a remarkable statement.

At Ardrossan, guests routinely arrived for parties on snowy evenings to find bottles of champagne plunged into the snow around the edges of the driveway. It was the best way to chill champagne, of course. At Ardrossan, the Meyer Davis Orchestra whiled away the smoky blue hours before dawn with such songs as "Shanghai Lullaby" and "Oh, Baby (Don't Say Maybe)" and "Fascinating Rhythm" and "I'm Just Wild About Harry." It was at Ardrossan where playwright and family chum Philip Barry, trundling through those massive rooms that spoke of privilege and whispered of its peculiar deprivations, got the inspiration for the 1939 play The Philadelphia Story, which made an icon of the young Katharine Hepburn, a star who had previously been dubbed box-office poison. Barry dedicated the play to Hope—on whom he had partially modeled Hepburn's character, the vivacious Tracy Lord—and her husband, Edgar. One year later, it became a wildly successful movie starring Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant. The house in the film, however, was not actually modeled on the one at Ardrossan. The moviemakers were convinced that Americans could never accept the idea that there were those among their fellow countrymen who lived on a scale so grand, lavish, and European.

"Newport, New York, and Palm Beach Four Hundreds— and even the elect of Boston—were an ordinary lot compared with Philadelphians," wrote P. A. B. Widener, heir to one of the city's greatest fortunes, in his autobiography. "The City of Brotherly Love," he continued, "shrine of American Liberty, was dedicated to the principles of snobbery more than any other American city." Here the monarchs modeled themselves after the aristocracy of England, creating a tightly woven world unlike any other in American life. Membership could not be gained simply, but rather was based on a combination of lineage, birthright, money acquired in the right manner, and immersion in the "proper" social institutions: St. Paul's and Groton as opposed to Andover and Exeter; Harvard and Princeton and Yale as opposed to Penn, Northeast Harbor as opposed to Nantucket.

It was a way of life embodied by Hope Montgomery Scott, who reigned for 70 years, until her death at the age of 90, as the unofficial queen of Philadelphia's Wasp oligarchy. Here was

a life so splendid and rarefied that even the fantasists of Hollywood found it unbelievable—a rare distinction. Yet beneath the

insulation of wealth, away from the anecdotes of dukes and the caviar and the endless quest for the perfect charming amusement, there was another story, a way of life marked by duty and complicated by the unrealities of her strange kingdom, where beautiful, seemingly effortless gestures concealed the pressure of larger expectations. Even the servants bowed to the unspoken. Consider, for example, the actions of Oscar Hugo Larson, the Montgomery-family butler who on a July night in 1952 served dinner in the impeccable fashion that had distinguished his 30-year tenure at Ardrossan. Then and only then, with his responsibilities fully discharged, did he turn his attention to his own affairs, which meant retiring to the pantry and shooting himself fatally in the head.

Continued on page 165

Continued from page 160

It all ended on an ordinary January afternoon earlier this year. Hope Scott had just led her pet donkeys, Sally Wheeler and Jenny, in from the fields and was returning them to their stalls when she fell. The cut she acquired on the back of her head was sizable. But she ignored it, as if it were too trivial for concern. She just went on, having her hair cut in the pageboy fashion she had always favored. When the stylist suggested that Hope see a doctor, she flatly refused. Hope Montgomery Scott brooked no interruptions. Cocktails were planned as usual. There were, for Hope, tedious things in life that could be postponed or delayed. The cocktail hour was not among them.

When Hope didn't come down from the bedroom of Orchard Lodge, one of the 38 properties that make up the Ardrossan estate, where she and her husband had lived since their marriage in 1923, her son Bob went up the stairs to find her. He went through the bedroom, past the scores of photographs that chronicled her life, past the scrapbooks wrapped in string and dry cleaner's plastic in which his mother had so fastidiously maintained the memorabilia of her existence, from her wedding invitation to the love letters from her husband to a typewritten list of her personality traits:

Tenacious Temper Desire for Power Vital Constructive

He walked past the full-length mirror where she had often paused to reassure herself of her almost perfect hourglass figure. He walked into the bathroom, where even more pictures of his mother hung, most showing her on horseback in stunning flight. He found her unconscious on the floor on her back, having apparently slipped on a needlepoint rug that had been made by her great-aunt. She awoke, and somehow, as if divinely instructed by an offstage whisper, she grasped her son's hand and kissed it. Then she fell into a coma and died a day later without ever regaining consciousness.

At the funeral several days later at St. David's Episcopal Church, hundreds gathered to pay final respects. The pews of the church became so crowded that hymnals were passed through open windows in the brisk January air to those friends who had arrived too late to find seats. The media covered the funeral as avidly as they had covered every chapter of Hope's saga. It had been a story animated by what her son Bob described as "enormous affection for life," an attribute which appeared to intensify with age and which seemed almost an addiction.

She reveled in naughtiness, and she clung with particular tenacity to those who abetted her in these pursuits, even when it meant going against the wishes of her family. She liked to say shocking things in her perfect lockjaw brogue and then wait for the reaction. Although she lived the life of high society, there was something sexually raw and elemental to her. She loved her party-girl image, and, despite the elegance with which she rehearsed the dramas of her life to reporters, her language was often saltier than a sailor's. She had a buoyant, unrelenting bawdiness.

"You dog," growled Hope after the chastity belt arrived. On occasion, says Annenberg, "during dinner parties she would put it on over her underpants and everybody would go mad!'

On one occasion, she dispatched cartoons about the sad and conflicted life of the penis. Another time, she handed out a Christmas card that exclaimed "Ho, Ho, Ho" on the front and on the inside read: "Santa always says that when he's coming." She loved dirty jokes, collecting them the way little boys collect baseball cards. Unable to keep them bottled up inside her, she established perhaps the world's most exclusive dirty-joke phone chain. At various times it included Walter Annenberg, former Philadelphia mayor Dick Dilworth, Brandywine River Museum and Conservancy president George "Frolic" Weymouth, and Devon Horse Show president Richard McDevitt. "I never told them, but I listened to them," said Annenberg discreetly, and McDevitt acknowledged that some of them were so off-color that he didn't even understand them.

When Annenberg was the ambassador to Britain, he made it a point of going to the big cities in England. When he was in Sheffield, famous for its silver, he received all sorts of gifts, including a chastity belt. Reluctant to send it back to the embassy ("They'll wonder if I went mad or something"), he was seized by a stroke of inspiration and instructed his hosts to send it to someone whom he described as an elderly person and a historian.

"You dog," growled Hope Scott after the present arrived. Later she planted flowers in it, and on occasion, said Annenberg, "during dinner parties she would put it on over her underpants and everybody would go mad with laughter!" But only when there were 12 for dinner, or at the very most 16. With more than 16, it might have been considered something of a spectacle.

The stories flowed as freely as the liquor at the big house on the day of Hope's funeral, and it was hard not to wonder if, beyond their feelings for Hope, her friends were trying to hold on to something they knew was long gone. The gilded age of Philadelphia society and the Wasp ruling class had passed with the Second World War and the G.I. Bill and the counterculture of the 1960s, when debutantes started showing up for coming-out parties in bare feet. Standing in those long shadows at Ardrossan on the day of the funeral, anyone could feel the echoes. But even the most uncritical eye could see that the big house had lost its legs years before. The brocaded wallpaper in the living room was secured in places with Scotch tape; the curtains in the ballroom were as flaky and frail as old skin. In some of the rooms, the furniture was threadbare. "You could put a million dollars into this place and it wouldn't even show," someone was heard to say during the reception. Those being charitable noted that the decline only made the house more charming and gave it a "livedin" quality. In fact, the house didn't have a "livedin" quality at all. At best it looked preserved, in silence. It was not a house full of life but, as one of Hope Scott's friends put it, "a shell holding memories."

Hope's debut was celebrated with a party where the Colonel greeted guests in a hunter's pink coat and silk top hat.

While the funeral reception took place, as the laughter swirled, a man living in another house on the estate sat alone at a metal table in the kitchen. It was the day after his 96th birthday. He faced a large window that looked out onto the gentle curve of a driveway. On one side of the drive was an immaculate sheet of green, on the other, a small fenced-off pen for animals. In the old man's heyday he had been an orator of Shakespeare as well as a founding partner at one of Philadelphia's most prestigious brokerage houses, but at this point it was hard to know how much of that he even remembered. On this day, he kept asking when his wife was coming home.

His name was Edgar Scott, and he had shared the cocoon of privilege that had been woven so tightly around Hope Scott. Now, unable to ward off the realities of old age, he had discovered that the immunities of grace and charm and entitlement offered little immunity after all. His mind played tricks as he grappled to figure out where on God's earth his Hope, his darling Hope, had gone off to, because he needed her.

"This is the only thing big enough to write my love on," he had written to her in 1931, using a piece of cardboard the size of a legal page. "I would give anything I have in the world (except you) if I could pass up this hideous trip. Tom Wanamaker told me last night . . . that he insists on your dining with him tonight. The lucky bastard! I wish you were dining with me! For once in my life the Fly Club looks to me like Sing-Sing. I adore you, o my baby. Please love me and miss me."

For nearly 65 years after that, by all accounts, that sweet and sizzling love, shared by both of them, never faded. Even after the ambulance took her.

"Where's my darling?" Edgar asked Hazel Holloway, their cook of 40 years.

"She died, she passed away," she gently told him.

"No she didn't," he protested.

"She went to heaven," said Hazel gently.

"Who took her?" he asked.

"The Good Lord," said Hazel.

"No," he said, his hands clasped together and raised to his lips, as if deliberating over something. Then he seemed to accept the fact that she was gone from this earth forever. But 10 minutes later he spoke again:

"Where's Hope?"

I had come to Colonel Montgomery like something out of a fairy tale. Born in 1879, one of nine children in a family that struggled for its pennies, he was riding his horse one day when he was thrown from his mount and knocked unconscious. When he awoke and saw the splendor of his surroundings, he vowed to himself that here, on this very spot, he would one day build a magnificent house.

So he did. He married well, first to a woman named Charlotte Hope Binney Tyler, whose family was in the banking business. And he did well in his own right, establishing an investment firm.

In 1911, when the massive Baldwin Locomotive Works was incorporated, Robert Montgomery—in what was described as a "famous coup" over the New York houses—handled much of the underwriting and made a profit of $1 million.

A year later, the big house at Ardrossan was completed, and the Colonel's family, which included four children, Hope, Mary Binney, Charlotte Ives, and Robert Alexander (Aleck), took up residence. It was grand, but not necessarily more grand than the other estates which surrounded it on the Main Line. These included the home of Charlotte Dorrance Wright, which was known as Ravenscliff; the Joseph H. DuBarry IV estate, with its house called Brigand; the Zantzinger estate, with its house called Maral Brook; and the Rosengarten estate, with its house called Chanticleer.

From the late 1800s to before W.W. I, it could have been argued that there was no better address in all of America than Philadelphia's Main Line. It wasn't accidental, for the Main Line had a deliberate design. It was a kind of super exclusive Levittown promoted by what was perhaps the mightiest corporation in the entire world, the Pennsylvania Railroad. Named after the late Main Line of Public Works, the railroad built double tracks 25 miles west to Paoli in the 1860s. In the 1870s, to encourage development, the railroad bought up a large tract of land near what is currently Bryn Mawr station and then established private zoning regulations for housing. The names of the towns were replaced with fancy-sounding Welsh appellations. The place became the assumed repository for railroad executives, who, as years passed, took over such estates as Cheswold, Ballyweather, Waverly Heights, and Boudinot Farms.

At Ardrossan, the Meyer Davis Orchestra whiled away the smoky blue hours before dawn with such soigs as "Shanghai Lullaby" and "Oh, Baby (Don't Say Maybe)."

The Main Line represented an escape from Philadelphia, a way of distancing themselves from the huddling masses while simultaneously exerting enormous financial power and control over those who remained. Roger Lane, a social historian at Haverford College, maintains that as early as the 1880s upperclass Philadelphians were scared of urban life. "Their social institutions, private clubs, and schools were designed to keep them living in an artificially homogeneous environment of their own," said Lane. "Philadelphia represents, more than most cities, a retreat from engagement in the world."

In his book Philadelphia Gentlemen, University of Pennsylvania sociologist emeritus E. Digby Baltzell provides three typical letters of introduction: one written for a young man from Boston, one for a young man from New York, and the other for a young man from Philadelphia. For the Bostonian, the emphasis was on Harvard and fluency in French and German. For the New Yorker, the emphasis was on how much money he had generated for his firm. For the Philadelphian, the emphasis was as follows:

"Sir, allow me to introduce Mr. Rittenhouse Palmer Penn. His grandfather on his mother's side was a colonel in the Revolution, and on his father's side he is connected with two of the most exclusive families in our city. He is related by marriage to the Philadelphia Lady who married Count Taugenichts, and his family has always lived on Walnut Street. If you should see fit to employ him, I feel certain that his very desirable social connections will render him of great value to you."

These values would ultimately prove devastating for the city. In his autobiography, P. A. B. Widener made it clear that his family neither forgot nor forgave the fact that his mother was never invited to the Philadelphia Assembly after she married his father. The Assembly, the oldest ongoing ball in the United States, dates back to 1748, and in terms of guest list is perhaps the nation's most exclusive.

Widener's mother was a Pancoast from a very good Philadelphia family. The problem was Widener's father, or more precisely his paternal grandfather, Peter. He was fabulously wealthy and was also beginning to amass one of the world's greatest art collections. His estate, the 110room Lynnewood Hall, set on 300 acres in Elkins Park, just north of the city, made Ardrossan look simple. But he had been common at birth. And that was not acceptable.

The Widener family had the last laugh. In 1942, when the time came for Joseph E. Widener to give away the art collection, which with its Rembrandts and Titians and Raphaels and Gainsboroughs was valued at around $50 million, he bypassed the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the National Gallery in Washington. As the Evening Bulletin so bloodlessly reported, Widener "cut off the Philadelphia Museum without a single painting."

Colonel Montgomery never suffered such indignities. He had birthright and lineage in ample proportions. His roots, according to some accounts, were traceable back to Roger de Montgomerie of Neustria in 912. The first Montgomery settled in the United States in 1701, on Doctor's Creek in Monmouth in what was then called East Jersey.

Formal and remote, with a perfectly manicured mustache and eyes that seemed able to pick up an out-of-place pebble at a hundred yards, Hope Montgomery Scott's father was not the kind of man who lent himself to easy intimacy. "He was very, very withdrawn," said his only son, Aleck. "I never knew my father well until practically I was a grown man."

The Colonel was a firm believer in maintaining the perfection of his kingdom. Near Ardrossan was a small group of houses called Banjotown, because the men who lived there liked to play the banjo when they weren't working. Perceiving these musical neighbors as undesirable, Montgomery bought up Banjotown, booted out the residents, and filled it with handpicked tenants.

Not surprisingly, Colonel Montgomery was also careful about potential suitors for his daughters. When Mary Binney, the middle daughter, exhibited serious talent as a classical pianist, one of her callers was Leopold Stokowski, the worldfamous conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Saying he would be damned if he was going to let his daughter marry a "Polack," the Colonel ordered one of the servants to burn Stokowski's hat.

His concerns for Hope, a young woman swept up by the attractions of horseback riding, band music, and "the party life," were different. "Helen Hope," he once said to her, "when you wake up in the morning, what you do is say, Wee, how much fun can I have today?"

Hope was tutored by governesses and did not attend formal school until her parents finally decided that something had to be done. They sent her to the Foxcroft School in Virginia, using a new horse as inducement. (It was common at this time for girls to take their own horses to boarding school for foxhunting.) The experiment was not successful. Hope really couldn't see much point in a formal education. "I thought that they wanted me to be educated to go to parties," she once said with a laugh. "That's all I thought."

After Foxcroft, she was—as she put it—"polished off' with various trips abroad. These included a two-month trip in a private boat up the Nile with a traveling party comprising her parents, her sisters and brother, her great-aunt, her mother's French maid, and her father's valet. Upon her return to Ardrossan she started riding the party circuit once again.

It was during this period of the early 1920s that she met the dashingly handsome Edgar Scott, who—unlike Stokowski—had all the necessary Philadelphia attributes. His grandfather Thomas A. Scott had been assistant secretary of war under Lincoln and then served as president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. His father was a member of the diplomatic service and had been stationed in Paris. Edgar had been educated at Groton and Harvard, where he had been president of the Lampoon. He fancied himself a playwright, although his career in this field went absolutely nowhere.

One night, when Edgar was sorting through a pile of invitations, he noticed that virtually all of the parties were being given for a woman named Helen Hope Montgomery.

They met one evening at a dinner party. He looked at her across the table. She looked back—and found him divine. They started dating, and on the night of a large dinner dance given by her uncle at the Ritz in Philadelphia, Edgar proposed.

She welcomed al sorts of new people, serving them Triscuits and macadamia nuts at cocktail parties and announcing to al who were present, "I adore gin!"

They announced their engagement in January 1923 at a little supper at the Wellington. Hope wore a frock of white brocade festooned with rhinestones.

At four P.M. on Thursday, September 20, 1923, at the Church of the Redeemer in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, Edgar Scott and Helen Hope Montgomery were married. Less than a week earlier, Philadelphian Bill Tilden had won the national singles title in straight sets at the Germantown Cricket Club, and George D. Widener's two-year-old colt St. James from Philadelphia had won the Futurity despite challenges by August Belmont's Ladkin and Mrs. Payne Whitney's Treetop. The old Lit Brothers on Market Street was advertising silk stockings for 98 cents and boys' school suits with knickers for $10. Coolidge was president. Babe Ruth was second in batting in the American League, with a .385 average. The curve of hope in America had no end in sight, and as Hope Scott, then 19, and Edgar Scott, then 24, embarked on their life together, it was hard to believe that there was a single place in the whole wide world that didn't belong to them.

For much of their lives it seemed that way: there were trips to Venice and the Lido in Paris, where a photo once caught Edgar in dreamy repose at a booth. There was lunch with Winston Churchill on Aristotle Onassis's yacht and that marvelous, crazy time at the Stork Club in 1951 when Hope sang for the Duke of Windsor. Another time there was a duet with Princess Margaret. In Barbados. Another time there was dancing the Charleston—with Josephine Baker. There were worlds of friends such as Helen Hayes and Claudette Colbert.

In her later years, when Hope Scott told her stories to the ubiquitous reporters who came to Orchard Lodge, the fun obscured the dark places. When she was interviewed in 1994, just after she had turned 90, a reference was made to her dimming eyesight. "I hit myself in the eye last year with a champagne cork," she told the interviewer with a laugh. "Can you believe it?' But it really wasn't so funny. Her eye had recently been operated on. The stitches ripped open, and a lens which had been implanted fell to the kitchen floor. Medical treatment was required, and in the course of all the various tests, it was discovered that Hope had cancer.

There were other flaws in the brocade, for Hope Scott was a woman who could be as autocratic and domineering as her father had been, a woman fighting to hold on to things that were ebbing away. Her temper could be fierce, and she could reduce family to the point of tears, particularly when she thought the things she valued most—her animals, her land, her way of life—were being threatened.

She loved the farm and the prizewinning dairy herd at Ardrossan, and these feelings represented what some say was the truest part of her. You could say that this attraction to the elemental was a legacy that dated back to 1912, when her father purchased a herd of Ayrshires, a breed distinguished by its extremely digestible milk.

Later, the dairy farm became an anachronism. It made for good copy and pictures, but lost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. When family members approached Hope Scott about the problem, her response was to invest even more in equipment. One of the first things her sons did after her death was sell off the cows. "It was easy to pull the plug," said her son Bob.

Continued from page 172

Continued on page 181

She had seen problems. She had witnessed the breakup of her son Bob's longtime marriage to his wife, Gay. The condition of her brother, Aleck, who lived in yet another house on the Ardrossan estate, had also not escaped her attention. Aleck, it seemed, took to his bed after convincing himself that he had become paralyzed from the waist down as the result of a World War II injury. There were other illusions as well.

"I got along with him because he was married to my sister," Aleck Montgomery once said of Edgar Scott. "We've always maintained a show of being a close family."

Throughout it all, she seized each lively moment with almost maniacal intensity. She seemed frightened of the quiet. As if, in the silence, she might hear something she preferred not to. Those close to her said she was almost never introspective, and she herself explained the roots of her personality on the basis of being an Aries. As her close friend Cathy Boericke put it, it seemed as if "she was fighting off sadness somehow."

She was physically fearless. Her abilities as a horsewoman were legendary. Nothing stopped her, not a broken nose or a concussion or a cracked vertebra. Finally the wear and tear was such that she had to have both hips replaced with steel ones. She approached the social aspects of her life with the same kind of abandonment. She had been raised to be charming and she was charming, indefatigably so, laughing at jokes and scattering compliments in perfect rote. In instances of social distress, her hand on your arm was as steady as a ship's anchor. "Don't leave me!" she would whisper. As if she had known you all your life. Even if she barely knew you at all.

Her confidences were often quotable. "I play this game," she told a man at a party. "I look around the room to see who would be the most fun to sleep with and you're always at the top of the list."

Her eccentricities were noteworthy. She sent notes to friends on "Things to Do Today" stationery with a blue etching near the top—an etching of a man and woman copulating. She drove a tractor over the fields of Ardrossan in a bikini top. Before her death she purchased—and wore—shoes with heels of clear Lucite filled with fluid. In the fluid, colorful balls bobbed. She loved the attention they got.

She had, according to Cathy Boericke, the need "to take risks with people and go over the edge a little bit." Even in her later years, she welcomed all sorts of new people into her life, serving them warm Triscuits and macadamia nuts at cocktail parties and announcing to all who were present, "I adore gin!" Bores were invited once, and while she was well trained in the art of how to make a bore never feel boring, they were generally never invited back.

Once, when a close friend and neighbor, Peter WesleyBurke, told her he would not be able to make it for a dinner party because he was sick in bed with a 104-degree temperature, she offered little in the way of condolence. Rather, she probed to see if there was any possible way he could still come, since it would now be an unlucky 13 for dinner, instead of 14.

"I lost my best friend, I lost my best joking companion. With her goes the lifestyle. I can carry it on for a while, but this kind of Edwardian English thing..."

"Can you sit up?" she asked.

When he said no, she put her pet dog at the table so there would still be 14.

In the big house at Ardrossan, Bob Scott, one of Hope and Edgar's two sons, lives alone now. He and a niece, Mary Remer, are the only two family tenants. She has the second floor and he has the third, and since the place has 50 rooms, they both have sufficient space. He says there are no ghosts in the house, but given what went on here—the great parties, the suicide of the butler in the pantry, the Jack Russel 1-terrier races on the back lawn—it seems impossible that there aren't. Everything about the house evokes the presence of someone, whether it is the cold eyes of the Colonel looking for the next crushed cigarette butt, or his kind and gentle wife needlepointing her way through life. (By the time she died, her work product included coverings for an entire couch, assorted pillows, and the full set of dining-room chairs.) One of the other singular ghosts, if there were ghosts, would be Charlotte, the youngest Montgomery daughter.

Both her parents were dead by the time Charlotte, or Miss Ives, as she was called, began to make her appearances for cocktails. The woman, who suffered from cerebral malaria which she had contracted while living in South Carolina, was confined to a wheelchair. But following what was apparently a strong family tradition, she refused to miss cocktails. She would take the elevator from her upstairs quarters to the first floor while the servants collected the necessary accessories, and then she would appear, like an Egyptian queen floating down the Nile, in her wheelchair, attended by servants, several whippets, a Great Dane, and a barnyard cat named Miss Kitty, who wore a collar of jewels. Miss Kitty lay in wait on Miss Ives's lap, ready to scratch anyone who approached. A three-tiered tray of sandwiches and goodies was laid out—for the animals, not the guests. Everyone understood the protocol, except for the actress and dancer Ann Miller, who upon one visit with Miss Ives began feasting from the animals' tray. No one had the heart to explain her error.

There was lunch with Churchill on Onassis's yacht and that marvelous, crazy time at the Stork Club in 1951 when Hope sang for the Duke of Windsor.

Bob Scott, the president of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, tends to be less starry-eyed about his mother than some. He admired her keen sense of public service and the innumerable hours she spent raising money for the Bryn Mawr Hospital, but he also recognized her need to be the center of the universe. When he was growing up, he saw little of her. She and Edgar lived in New York on Beekman Place, and Edgar worked for the New York Stock Exchange. When they came back to the Main Line, it was often for foxhunting.

But now that Hope is gone, her son misses her terribly, the dirty jokes, the way she knew the names "of all those goddamned cows." In the aftermath of Hope's death, significant changes have already taken place at Ardrossan. The dairy herd has been purchased, and while Scott gives assurances that the 750 acres of the estate will not simply be sold to developers, it is inevitable that it will become something different, maybe a park or a golf course.

"It's very sad," said Bob Scott. "It's compounded by the demise of my marriage, reaching what you call normal retirement age. I didn't realize how depressing it would be. It doesn't hurt. My knee hurts. But it's the death of a portion of me. This is the portion of my life that has no promise of resurrection. He sounds like Richard Burton, each letter of every word perfectly articulated. In a pair of pale-green suspenders he sips a glass of Beaujolais while a pack of beagles bark in the distance.

Heading down the driveway of Ardrossan, one finds it impossible not to think about Bob Scott living in that big and empty house with its 38 family portraits. Impossible not to think about the way he had recited the motto of Groton in perfect Latin like an incantation. At one point, he had said that he had grown up in a "picture frame of privilege" and had no regrets about it. But as he had stood in a tiny little kitchen between the rooms of what had once been his mother's nursery, grinding up coffee beans, a different image had emerged.

"With her goes the lifestyle," Bob Scott said of his mother. "I can carry it on for a while, but this kind of Edwardian English thing ..."

Five days later, on the last Friday in May, his father, Edgar, died.

Hope had taken care of him with utter devotion in those final years. At times, he got quite disoriented, and he became convinced that his French cousins, who had died 50 years ago, were coming to visit Ardrossan. Over and over he asked Hope about the French cousins. Was there enough caviar? Had arrangements been made to have Le Monde delivered to the house? Who was going to pick them up at the train station?

It was driving her mad, the goddamned French cousins who were dead, and she knew she had to do something. The day of their supposed arrival, she turned to Edgar.

"Darling, the most awful thing has happened," said Hope. "The plane went down in the middle of the Atlantic and they were all killed."

"Fine," said Edgar. "I never liked them anyway."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now