Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LADY TRIUMPHS

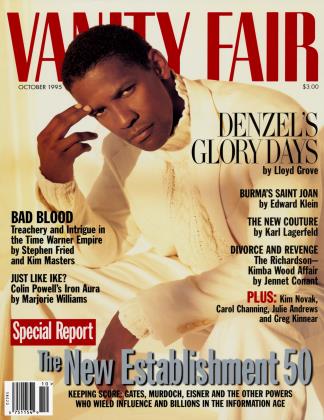

Six years under house arrest made Aung San Suu Kyi, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, a legend. Her release is a victory over Burma's brutal strongman

EDWARD KLEIN

Dispatches

'Call me Suu."

Aung San Suu Kyi was showing me around the grounds of her lakeside villa in Rangoon, where she had been held under house arrest for six years. I had made a number of attempts to see her since she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. But it was only after her release this past summer by the generals who rule Myanmar—as Burma is now known—that I was finally able to meet the world's most famous political prisoner.

Pictures don't capture her special aura. She was wearing a lungi, the traditional Burmese sarong, which hugged her hips and gave her slender figure a sinuous grace. A sprig of yellow flowers dangled from the bun at the nape of her neck. Though only five feet four, she possessed a commanding presence.

"It's hard to think of you as just plain Suu," I said.

"Perhaps you'll change your mind when you get to know me better."

I took out my notebook and asked, "Where shall we begin?"

She looked around and said, "Right here. On the day they placed me under arrest, this garden was still quite beautiful. There were lots of white Madonna lilies, fields and fields of them, and frangipani, and fragrant yellow jasmines, and gardenias— all highly scented flowers—and a flower from South America that changes its color as it matures and is called 'yesterday, today, and tomorrow.'

"In the beginning," she continued,

"I'd go out and work in the garden and talk with the guards. There were 15 soldiers, all of them armed. But a garden like this requires quite a lot of money to keep up, and I couldn't afford to take care of it. Of course, I refused to accept anything from the military."

She spoke with a British accent, which she had acquired while at Oxford University. When she wanted to emphasize a point, she curled her hands into fists and hammered them against her sides.

"Sometimes I didn't even have enough money to eat," she went on. "I became so weak from malnourishment that my hair fell out, and I couldn't get out of bed. I was afraid that I had damaged my heart. Every time I moved, my heart went thump-thump-thump, and it was hard to breathe. I fell to nearly 90 pounds from my normal weight of about 106. I thought to myself that I'd die of heart failure, not starvation at all. Then my eyes started to go bad. I developed spondylosis, which is a degeneration of the spinal column." She paused for a moment, then pointed with a finger to her head and said, "But they never got me up here.

However, I did have to let the garden go. When they released me, one of the first things I did was have a team of gardeners come and clear it out. It was full of snakes, and had become dangerous."

The garden was now nothing more than a mud pile, for her release had come at the height of the monsoon season, when drenching rains turn vast expanses of Burma into a vaporous waterworld that stretches from the shores of the Andaman Sea nearly to the foothills of the Himalayas. Her freedom had also coincided with Wa-zo, the advent of L Buddhist Lent, a season of ft fasting and penitence when teenage boys shave their heads and temporarily enter the monastic order, and the country's hundreds of thousands of monks retreat from the outside world in search of Nirvana, the ultimate deliverance from suffering and misery.

We approached her two-story villa. Like most buildings in Rangoon, it was in a state of ruin. Its crumbling stucco walls were stained black with mildew, and it looked as though it hadn't seen a coat of paint since the British granted Burma its independence in 1948. The quaint decay of Rangoon made me feel as though I had stepped back in time into a novel by Somerset Maugham.

I took off my shoes as I entered the foyer, and was confronted by pages of handwritten political statements which she had posted in defiance of her captors. To raise money during her years of confinement, she had sold all her valuable furniture, keeping only a dining-room table and a piano, which she had stopped playing after a string snapped during one of her temperamental poundings. One of the old family photos on the wall showed her as a baby with her father, the founder of modern Burma, who was martyred by an assassin's bullet in 1947, when she was two.

All her life she has been obsessed with the father she never knew. She adopted his famous name, Aung San (pronounced

Awng Sahn), and added it to her given name, Suu Kyi (Sue Chee). A heroic statue of her father stands in the middle of a park in Rangoon, and it is easy to see from its expression that Aung San Suu Kyi is his spitting image.

'I always felt close to my father," she said. "It never left my mind that he would wish me to do something for my country. When I returned to Burma in 1988 to nurse my sick mother, I was planning on starting a chain of libraries in my father's name. A life of politics held no attraction for me. But the people of my country were demanding democracy, and as my father's daughter, I felt I had a duty to get involved."

As she spoke, a crowd was gathering in the stagnant afternoon heat outside her iron gate on University Avenue. Millions of her countrymen had learned of her release from the Burmese-language shortwave broadcasts of the Voice of America and the BBC. Neither the state-controlled television station nor the regime's daily mouthpiece, The New Light of Myanmar, had summoned up the nerve to acknowledge her freedom.

The junta's nervousness was understandable. In the minds of her countrymen, Aung San Suu Kyi had become a legend. Friends and foes never referred to her by name; they called her the Lady. The only other Burmese who inspired such awe was Ne Win, the country's longtime strongman, who, though now 84 and in the twilight of his rule, was referred to as the Old Man.

An aide came to tell her that it was time to address the crowd. I followed her outside, where I saw a team of her supporters lugging two huge Peavey speakers up the driveway to the gate. They lifted the speakers onto the limbs of trees and attached the wires to an amplifier. A desk was placed against the verdigris-covered gate, and Aung San Suu Kyi climbed on top and greeted the crowd outside. It roared its approval.

There were perhaps 500 people standing on both sides of the street, including a large number of students, as well as monks in saffron robes and nuns in pink vestments. Many of the women and children had coated their faces with thanaka, a pale-yellowish paste made from the bark of a tree, which turns to powder and is used as makeup and sunblock. They looked like the gathering of an African tribe.

I was struck by the courage of the people; after all, the last time they had turned out en masse to support leaders demanding democratic reform, the army had met them with tanks and machine guns, murdering far more people than were killed in the bloody massacre of Chinese students in Beijing's Tiananmen Square a year later.

"The people of my country were demanding democracy, and as my father's daughter, I had a duty to get involved."

When I stepped back from the gate, I found myself standing next to one of her closest political associates. He had been imprisoned several times in the past 30 years, the last time in the notorious Insein Prison, in the northern suburbs of Rangoon, which is, appropriately enough, pronounced "Insane" Prison.

"I knew her father, and she reminds me so much of him," he told me. "The way she smiles and tilts her head—all her gestures are similar to his. When she came back to Burma, she had no intention of becoming a celebrity. She was inexperienced in politics. It was a hard destiny. But she had the gift. And she matured in six years of house arrest."

He looked up at Aung San Suu Kyi, who was exhorting the crowd. "We must avoid having extreme ideas," she told them. "Think before you do anything!" Since her release, she had struck a conciliatory tone. But it was possible that a real test of her leadership would come the next day, Martyrs' Day, a national holiday commemorating the assassination of Aung San and six of his colleagues. Everyone in Burma was wondering whether Aung San Suu Kyi's plans to lay a wreath at her father's mausoleum would set off a fresh round of clashes between the forces of the Lady and those of the Old Man.

That night I sat in the dining room of the Inya Lake Hotel, a mile north of Aung San Suu Kyi's villa, and watched as searchlights played over the murky water and boats patrolled the shore in front of the residence of Ne Win. The Old Man's compound is ringed by a steel fence and protected by land mines. Two thousand troops were reportedly stationed nearby.

In his younger days, Ne Win was a frequent traveler to the West. On a whim, he would collect a contingent of his ministers and fly to Vienna, where he consulted a famous psychiatrist by the name of Hans Hoff. Many of his trips were bankrolled with bags of rubies and other precious stones, which are found in profusion in Burma. In April 1987 he made a secret, seven-day trip to Oklahoma City to visit Ardith Dolese, a wealthy American woman, whom he credited with having helped save his life almost 40 years earlier in England by referring him to a doctor when he was ill.

In recent years, no Westerner has laid eyes on the reclusive former general. His photos have disappeared from billboards and placards throughout Burma. His two principal contacts with the outside world are his daughter, Sanda Win, a physician with the rank of army major, and his protege, Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt, who heads military intelligence. Sanda Win and Khin Nyunt are believed by some to have orchestrated the campaign of vicious slander that led up to Aung San Suu Kyi's house arrest. Among other things, it was charged that she indulged in "foreign" sexual practices with her British-born husband, Michael Aris, a professor of Tibetan studies at Oxford.

According to the official line, Ne Win has retired, and the administration of the country is in the hands of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), whose baleful acronym is pronounced "Slork." The SLORC is headed by Senior General Than Shwe. But nearly everyone is convinced that the Old Man continues to call the shots and that he exercises power in the tradition of many Oriental despots, as a mysterious, sinister presence who chooses to remain hidden from public view.

Ne Win spends most of his time alone in his vast library, reading Buddhist sutras and meditating. He is notoriously superstitious, and regularly consults numerologists, soothsayers, and astrologers. Like many in his country, he believes that the world is inhabited by supernatural spirits called nats. To cheat fate he indulges in the widespread mystical Burmese practice called yedayache. Thus, he has been known to walk backward over a bridge at night and circle his plane over his place of birth while seated on a wooden horse. When one of his astrologers warned him that he would come to an unhappy end unless he shot himself, he took out a pistol and fired at his reflection in the mirror. Many Burmese are convinced that the reason he renamed the country Myanmar and its capital city Yangon was not to eliminate the vestiges of British colonialism but to ward off evil spirits.

Ne Win has built his own pagoda in the center of Rangoon, not far from the Shwedagon Pagoda, which, according to Nicholas Greenwood's Guide to Burma, is the biggest Buddhist temple of its kind in the world—its gold leaf alone reputedly weighs 60 tons. This is part of his effort to store up Buddhist merit and presumably assist himself on his way to Nirvana. Despite Burma's Buddhist tradition of compassion, its long history is full of stories of brutality; the country's last king, Thibaw, who ruled from 1878 to 1885, sewed up his opponents in sacks of red velvet and had them trampled to death by royal elephants. But few Burmese leaders have matched Ne Win's record for utter incompetence and sheer barbarity.

Shortly after he seized power in a 1962 coup, Ne Win sealed Burma off from the rest of the world and turned it into a hermit state for 26 years. He instituted a preposterous program called the Burmese Way of Socialism, which wrecked the economy and plunged Burma's people into such abject poverty that today the per capita income is $200 a year, among the lowest in the world. He poured his meager resources into the army, which was called upon to wage war against more than a dozen rebellious ethnic minorities, as well as the Burmese Communist Party, whose breakaway members were in cahoots with powerful Chinese drug lords. But although most of the ethnic insurgencies have been subdued, and the Communists have disappeared as a threat, Burma's Golden Triangle still accounts for 60 percent of the world's production of heroin.

i haven't touched a penny of the Nobel Prize money. The money is for the people of Burma."

In recent years, limited private enterprise has been allowed to resume in Burma. The regime has declared 1996 "Visit Myanmar Year," and hotels are springing up in Rangoon, Mandalay, and the ancient city of Pagan. But Ne Win's army still runs the country as its economic fiefdom. Families of highranking officers live in neighborhoods where there are telephone lines, electricity, and running water-services that are not ordinarily available. They have special stores and even a planned medevac service to nearby Bangkok and Singapore. Their children go to the best schools and get the best jobs.

Meanwhile, the average Burmese struggles with a 30 percent annual rate of inflation, which makes it hard just to put food on the table. Young men are rounded up on the streets of cities and towns and shipped off to border areas, where they are used by the army as porters and human minesweepers. Girls are sold as prostitutes in Thailand. If they return, they are often H.I.V.-positive. There are at least a thousand political prisoners in the country's dungeonlike jails, where they are subjected to torture and some of the most inhumane conditions found anywhere in Asia. Nevertheless, the SLORC generals go out of their way to portray themselves as the righteous guardians of Buddhist principles, and are frequently televised giving alms at well-known pagodas.

Burma's people suffered through all of this in relative silence until 1987, when, out of the blue, Ne Win abolished nearly 60 percent of the country's money supply. The monetary unit is the kyat—6 to the dollar but up to 120 on the black market. He did away with 75-, 35-, and 25-kyat banknotes and replaced them with 90and 45-kyat denominations. The reason? Ostensibly to fight inflation, but according to most people because 90 and 45 are divisible by 9—his lucky number—and the digits in them also add up to 9. Predictably enough, the effect of this massive demonetization was catastrophic, for it wiped out most savings. Riots ensued, students took to the streets, and the demonstrations grew into a national movement for the restoration of democracy. Suddenly Ne Win, who had been portrayed as the legitimate heir of Burma's independence leader, Aung San, was being challenged for power by Aung San's daughter.

More than 100 foreign journalists were on hand when Aung San Suu Kyi showed up at the Martyrs' Mausoleum. She was dressed in mourning, and looked stiff and somber as she laid three wreaths of orchids on her father's grave. If the journalists had come expecting dramatic conflict—there had been speculation that hundreds of thousands of Burmese might turn out for the occasion—they were sorely disappointed. Rangoon was crawling with soldiers, and although it was a national holiday, there was hardly a Burmese civilian on the street. They were too scared to go out.

However, those who had access to a TV set were treated to a startling spectacle later that day. The state-run television station carried a 65-second video clip of Aung San Suu Kyi's public appearance, the first official acknowledgment after more than a week that she had been freed from house arrest.

That afternoon she invited the entire press corps to her villa for a tea party. The gate swung open at three P.M., and still photographers and video teams were the first to be let in. They were asked to take off their shoes and then were herded into separate rooms—stills in the dining room, videos in the reception room. After a while, Aung San Suu Kyi came down the staircase, looking cool in a starched white muslin blouse and a lungi. She went into the still photographers' room, where she submitted to their flashbulbs. Then she went into the other room and posed for the video cameras.

Few Burmese leaders have matched Ne Win's record for utter incompetence and sheer barbarity

She walked out onto a scruffy terrace, where the tea was being prepared, and the cameramen, who didn't have time to retrieve their shoes, spilled out after her into the muddy yard in their socks. Some of them sank up to their ankles under the heavy equipment.

"How is this?" Aung San Suu Kyi asked them. "Do you have enough of me?"

I began to worry about her security.

"She has no security," one of her aides told me. "Everybody is really scared. It took only one gunman to eliminate Mahatma Gandhi. But she has resigned herself to her fate on this score."

By now, the print press had been let into the compound, swelling the number of journalists. Swirling groups of reporters and cameramen were pressing in upon her. She didn't seem to mind. She joked with them. They laughed. And then they did the most remarkable thing: they began asking her for her autograph.

She responded to all this with good humor and poise. The press was completely won over. The sweaty cameramen put down their equipment and drank tea out of little china cups. The occasion was a huge public-relations success.

She spotted me in the crowd and came over. "Well, are you prepared to call me Suu yet?" she asked.

"Maybe Saint Suu," I said.

"Saints are only sinners who go on trying," she said, "so if I'm a saint, I'm of that sort."

"What are your sinful qualities?"

Without a moment's hesitation, she replied, "I have a flaming temper, for one, which I hope I've brought under control. Impatience, for another. I'm a lot more patient now." Then she caught .herself and smiled. "You don't expect me to record all my sins, do you? You'll have to get to know me better."

Her life has been shaped by three great losses.

To begin with, there was the death of her father, whom she never had a chance to know. When she sought to recapture him in later years by writing his biography, she turned up evidence indicating that he had left her a puzzling legacy. For upon close inspection, Aung San turned out to be an ambiguous national hero. To rid Burma of British colonial rule, he had thrown in his lot with the Japanese in 1940, and in 1943 had received a medal from Emperor Hirohito himself. Later, when he sensed that the tide of war was shifting, he struck a deal with Lord Mountbatten and fought alongside the British against the Japanese. During World War II, Burma suffered greater damage than any other Asian countries except China and Japan. Aung San was, at various times, for and against the Burmese Communist Party. Like John F. Kennedy, another politician who was cut down before he could fulfill his promise, Aung San was a supreme pragmatist bordering on opportunist.

Then, a second tragedy—a brother drowned before Aung San Suu Kyi's very eyes. "I think in some way the death of my second brother affected me more than my father's death," she told me. "I was seven and a half when my brother died. We were very close; we shared the same room and played together. As I remember, he dropped his little toy gun at the edge of the lake and went back to get it. His sandal got dislodged in the mud, and he ran back and gave me the gun. Then he went back for his sandal, and he never came back. Then my mind goes blank. I have a slight mental block about this."

Then she lost her country, when Ne Win and his military henchmen launched their 1962 coup. She left Burma when she was 15, and didn't return, except for short visits, for 28 years.

Her mother, who had a mixed Christian-and-Buddhist background, saw to it that her daughter was educated in strict convent schools, in Burma and later in India, where from 1961 until 1967 she served as Burma's ambassador. She also made sure that her daughter was given lessons in Japanese flower arrangement, horseback riding, piano, cooking, and sewing.

"I went to lunch at their house in New Delhi," said British journalist Harriet O'Brien, whose father was a diplomat in India in the mid-1960s. "Her [mother's] clothes matched perfectly. Her hair was done up perfectly with a flower in the bun. She let you talk, and she laughed gently, and then she made biting remarks. Suu arrived, and I remember being struck by how she plunged into the conversation about politics. She was 17 or 18, and she was already a commanding person.

"Her mother was shrewd, funny, and generous, and felt that Suu was surrounded by people who deified her father, which she didn't think was good for Suu," she continued. "Her mother was a bit more relaxed than Suu. You could have a good chuckle with her. Suu was more correct."

Patricia Gore-Booth, whose husband, Sir Paul (later Lord) Gore-Booth, was at the time Britain's high commissioner in New Delhi, recalled Suu as a teenager on the verge of womanhood. "When it was decided that she should go to England for her university degree, and had secured a place at St. Hugh's College, Oxford, we suggested to her mother that she should make our London home her base while in Britain," she said. At the GoreBooths' house in Chelsea, Suu met many of the leading British politicians of the day, as well as the young friends of the Gore-Booths' twin sons. Among those friends was another set of twins, Michael and Anthony Aris, both of whom were studying to be Orientalists. Michael was tall, extremely handsome, and bookish. "I'm sure that Michael lost his heart to Suu immediately," said Patricia GoreBooth, "but she would have had, at that time, no idea or intention of marrying anyone other than a fellow Burman."

Ann Pasternak Slater, a niece of Boris Pasternak's and Suu's classmate at Oxford, nicknamed her Suu Burmese. "Everyone was on the hunt for boyfriends, many wanted affairs, sex being still a half-forbidden, half-won desideratum," she has written in an essay in Freedom from Fear, a book Michael Aris compiled out of writings by and about his wife. "Being laid-back about being laid was de rigueur—except that most of us were neither laid back nor laid. ... To most of our English contemporaries, Suu's startled disapproval seemed a comic aberration. One bold girl asked her, 'But don't you want to sleep with someone?' Back came the indignant reply—'No! I'll never go to bed with anyone except my husband.' "

Two years after receiving her degree, Suu went off to New York to work at the United Nations. While there, she began to form her first serious political ideas. She also wrote scores of intimate letters to Michael Aris in Bhutan, where he was employed as a tutor to the royal family. "I only ask one thing," she wrote, "that should my people need me, you would help me to do my duty by them. . . . Would you mind very much should such a situation ever arise? How probable it is I do not know, but the possibility is there. . . . Sometimes I am beset by fears that circumstances and national considerations might tear us apart just when we are so happy in each other that separation would be a torment. And yet such fears are so futile and inconsequential: if we love and cherish each other as much as we can while we can, I am sure love and compassion will triumph in the end."

As only the eighth woman to win the Peace Prize, she instantly became the daring of the Clinton administration's State Department.

Suu was aware of the prejudice in her country against Burmese women who married foreigners; indeed, the Young Men's Buddhist Association of Burma passed a resolution against the practice in 1916. Marrying a foreigner was clearly not a wise move for someone who was thinking about a political career in Burma. Yet, in 1972, that was probably the furthest thing from Suu's mind, and she and Michael were duly married in a Buddhist ceremony at the Gore-Booths' home in London.

During the first few years of her married life, Suu avoided any involvement in the anti-Ne Win emigre groups that operated out of London. She was engrossed in her courses in English literature. Michael was getting his graduate degree in Tibetan studies. Their house in Oxford overflowed with books, the laughter of friends, the smells of Suu's cooking, and the sounds of their first child, Alexander, who was bom in 1973.

However, a number of events occurred in 1977 that changed the entire course of her life. In that year, a second son was bom, and they named him Kim. "To her intense distress," Ann Pasternak Slater writes, "Suu found she could not feed him. Kim was kept happy, bottle fed and healthy, but with dimmed lamp she nightly tried to nurse him in vain."

That year, too, Suu turned 32, the age at which her father had been assassinated. From now on, she would be his senior, and in a mystical way she would be responsible for carrying out her father's Karma, or destiny.

Also in 1977, a Buddhist monk named Rewata Dhamma, who had known Suu and her mother in New Delhi, showed up in Oxford. "I saw her at the Buddhist center in Oxford," the monk told me when I tracked him down in Birmingham, England, where he runs a Buddhist center. "She came with her husband and some Tibetan lamas and her two small children. At first I didn't recognize her, because she was wearing a Bhutanese native dress. But then she introduced herself in Burmese as the daughter of Aung San.

"She said that she wanted me to teach her sons about Buddhism," he continued. "I had been studying Mahayana Buddhism in India, which is different from the Theravada Buddhism that is prevalent in Burma. In Burma, the monks receive respect and blessings. They take and take. Mahayana stresses selflessness, doing things for others, giving back. One day she said, 'I'm studying Burmese language, culture, politics, history, and tradition. I've lived outside Burma for many years.' She implied she was preparing herself, in case she needed to go back."

From then on, Suu displayed a growing interest in the wider world. She taught herself Japanese and eventually moved for a year to Japan, where she studied at the University of Kyoto and researched her father's activities with the Japanese. Michael Aung-Thwin, a Burmese scholar, had an office adjacent to Suu's at the University of Kyoto in the mid-1980s.

"She had an aristocratic air about her," he said. "She always thought of herself as part of the Burmese aristocracy, and that she had a right to Burma's throne because of her father. . . . She was charming, intelligent, but very stubborn, very authoritarian. She was in favor of overthrowing the military, but she was personally authoritarian herself. Once, I remember her saying, 'It is my destiny to rule Burma.' I said, 'You should have a relatively easy time because of your father's name.' She bristled. 'I will do this myself,' she said. 'It won't have anything to do with my father.' 'Then why do you use your father's name?' I asked. But she just repeated, 'I will do it myself.' "

Continued on page 143

Continued from page 134

In the spring of 1988, Suu flew to Rangoon to be by the side of her mother, who had suffered a severe stroke. When she arrived, she found the country in a state of turmoil. In one incident, 41 students suffocated to death in a police van; in another, a group of students were forced by troops into Inya Lake, where they presumably drowned. By that summer, there were riots and mass demonstrations throughout Burma.

Ne Win electrified the country by announcing that he was stepping down as chairman of the Burma Socialist Programme Party. Jubilant crowds surged into the streets, where they were met by troops with guns. Casualties mounted. The demonstrations grew larger, until they numbered in the hundreds of thousands. There was talk of putting Ne Win on trial, and some thought that the Old Man was preparing to flee the country.

On August 26, Aung San Suu Kyi spoke to a throng of 500,000 on the slopes below the Shwedagon Pagoda. She was an instant hit, and over the following months she became the most prominent leader of the democratic opposition. She toured the country, drawing vast crowds. Wherever she went, she was harassed by the army. "While campaigning in Danubyu," writes Professor Josef Silverstein, an expert on Burma, "an army captain ordered six soldiers to load and aim their rifles at her; before the countdown ended an army major stepped forward, countermanded the order and prevented her assassination."

Despite incidents such as that, she grew bolder. She dared to attack Ne Win by name in a country where people referred to him only as the Old Man, or Number One. And she called on the military to overthrow the strongman. "Ne Win is the one who caused this nation to suffer for 26 years," she said. "Ne Win is the one who lowered the prestige of the armed forces. Officials from the armed forces and officials from the State Law and Order Restoration Council, I call you all to be loyal to the state. Be loyal to the people. You don't have to be loyal to Ne Win."

Less than a month later, she was placed under house arrest.

'I set my alarm clock for 4:15," she said, describing for me a typical day under house arrest. "But eventually I was used to getting up at that hour, and I woke up on my own. I tidied myself up; you want to feel clean and tidy when you meditate. I sat at the foot of my bed, on the mattress, in the usual position of the half-lotus. I can't manage a full lotus. I practiced what we call insight meditation. I concentrated on my breathing.

"At 5:30 I turned on my portable Grundig shortwave radio and listened to the BBC World Service news. At six, it was the Voice of America Burmeselanguage broadcast. At 6:30, the BBC Burmese-language broadcast. At seven, the Democratic Voice of Burma, which is transmitted from Norway. I felt very much in touch with the outside world.

"Then I had an exercise session, starting off with aerobics. My husband brought me an exercise machine on one of his visits, a NordicTrack, and I spent 20 minutes on that every day. Every time I went on that machine I blessed my husband. Next I bathed and dressed. I tried to read something before breakfast, some sort of religious work, something Buddhist, but not always.

"For breakfast, I generally had fruit, tea, or milk. Bread got very expensive. On the weekend, I'd have a boiled egg. I found myself getting less interested in food. I discovered what I liked was cooking for others.

"I had a lot of discussions with my liaison officer, a lieutenant colonel. The advantage of being in house arrest is that you are in your own home. I treated him as a visitor who came to see me. Sometimes we had pleasant conversations about food..We discussed politics. He tried to put forward his point of view. . . . I know he reported back to his superiors.

"I read a lot of biographies. They taught me how other people faced problems in life. Mandela. Sakharov. Mother Teresa. People felt they had to send me books about people who were in prison.

"I entered menopause. It wasn't so difficult. I kept thinking that I wished I had been put in at a younger age, so that after my release I would have a longer period to work.

"I dreamed about my husband and sons, but I don't dream that often, and I don't put much store in dreams. I learned not to think about my sons and my husband, not to let my thoughts dwell on them. It wouldn't help them or me. My marriage will last, if I have anything to say about it. Of course, you should ask Michael, since he has a say, too. But it won't be a normal marriage. It hasn't been a normal marriage for a long time."

"My marriage will last, but it won't be a normal marriage. It hasn't been a normal marriage for a long time."

Aung San Suu Kyi's opponents argued that she wasn't, technically speaking, under house arrest; she was free to leave whenever she wanted to, they said, as long as she left the country. Her choice was to stay and fight for what she believed or to return to her husband and two sons. The regime kept pressure on her by refusing to allow her husband and sons to visit her for months at a time. Both children suffered, though the strain was worse for Alexander, the elder.

Her husband sent her books, letters, and provisions through the British diplomatic pouch. When the SLORC revealed this privileged foreign connection in an effort to taint her in the minds of the Burmese public, she put a stop to the practice. She lived largely on the proceeds of Freedom from Fear, the book her husband had put together. "I protested to my husband that he published letters that should be private," she told me. The money from the book was deposited in a Rangoon bank, where her maid made withdrawals to purchase daily necessities. The Nobel Peace Prize and the Sakharov Prize, which she also won, carried honorariums totaling close to $1 million, and her opponents leaked stories deriding her claims of penury. This made her indignant. "I haven't touched a penny of the prize money," she told me. "The money is for the people of Burma."

Ironically, the Nobel Peace Prize made it harder for Aung San Suu Kyi and her captors to strike a compromise. As only the eighth woman in history to win the Peace Prize—and the first woman to receive it while in captivity— she instantly became the darling of every human-rights group in the Western world, as well as of the Clinton administration's State Department. Everybody let her know that they were counting on her to fight the good fight. As for Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt and his xenophobic colleagues in the SLORC, they were more determined than ever after the Nobel announcement not to be seen kowtowing to the hated foreigners.

By the beginning of 1994, after she had been under house arrest for four and a half years, cracks began to appear in the SLORC'S position. The country's economy was finally beginning to show some encouraging signs of life under the stimulus of free-market forces. But the generals knew that Burma wasn't going anywhere unless it received massive infusions of aid from Japan and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank. That was unlikely to happen as long as they kept a famous Nobel laureate under house arrest. Indeed, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights was considering a harsh condemnation of Burma, and some members of the U.S. House of Representatives were ready to submit a bill calling for a full-scale tradeand-investment embargo, like the one used against South Africa.

It was in hopes of avoiding this wave of international censure that the SLORC began to allow Aung San Suu Kyi to receive visitors. The first to arrive was Bill Richardson, a blustery Democratic congressman from New Mexico and a friend of President Clinton's who is fond of carrying out one-man international peacekeeping missions. He was followed by none other than Aung San Suu Kyi's old Buddhist acquaintance, Rewata Dhamma, who visited Rangoon three times between May 1994 and January 1995 and mistakenly thought he was on the brink of brokering a deal for her release.

"In the summer, she had told me that she wanted national reconciliation," Rewata Dhamma told me. "She said, 'Democracy is not something you get from others; you have to build it yourself. If Nelson Mandela can work with whites, I can work with the SLORC.' But then, in January, she changed her tune. 'You came too late,' she told me. What happened was the democratic groups outside of Burma got to her and hardened her position against SLORC."

In the end, it was the SLORC that blinked. The generals released Aung San Suu Kyi unconditionally. As I prepared to leave Rangoon, Michael Aris arrived with their son Kim. Lest anyone think that the regime had gone soft, however, high-ranking officers reminded me that there is a clause in the pending constitution prohibiting anyone married to a foreigner from becoming president.

"I'm not that different a person now after six years," she told me. "I hope I'm spiritually stronger. I've always asked for a dialogue. People say there's something new in that. There isn't. If I've mellowed, I'm pleased. People should mellow with age. I hope I will be aging gracefully."

One of her closest advisers didn't entirely agree. "In the beginning," he said, "she didn't know how to pick up the ropes. But her sense of mission grew when they placed her under house arrest, and it came to her even more strongly when she won the Nobel Peace Prize. I was the first person to meet her after her release. I could see that she had matured in the past six years. In 1989, when she first started out, she looked like a schoolgirl. Today she looks like a much older woman than she is."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now