Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowit's a wonderful life

JAMES WOLCOTT

Caving in to the charms of thirtysomething

Mixed Media

ABC's thirtysomething has become a mediasomething. There hasn't been a trendsetter so attuned to the stammering emotions of educated audiences since Diane Keaton hemmed and hawed through Annie Hall. The series has even become a transatlantic succes d'estime, welcomed by English critics who one had imagined would narrow their nostrils at this waxy yellow buildup of bourgeois angst. One enthusiast said that it was refreshing to hear American men discussing their feelings. English men, she said, seldom discussed their feelings, assuming they had any.

Yet there are hostile holdouts to this craze. Black critics charge that the show consists of white people whining. White proles wince too. Still others adapt. One episode of Fox's knuckle-dragging comedy Married.. .with Children had A1 Bundy (Ed O'Neill) building his dream bathroom down in the basement, only to find himself blocked upon its completion—constipated. A disgruntled A1 slumped in front of the television just as an ABC announcer said to stay tuned for. . .thirtysomething. Blessed relief crossed Al's caveman brow. He lifted a magazine off the coffee table, folded it under his arm, and with satisfied footsteps headed down the stairs to his reading room. The mere mention of thirty something had moved his bowels. For missing links like A1 Bundy, thirtysomething is a safe and gentle laxative.

Like A1 Bundy, I looked askance at the show at first, but unlike Al's, my response was not intestinal. I had a builtin resistance based on a clash of value systems. Not so much cultural bran as a homemade quilt woven to ward off The Big Chill, thirty something is about caring, closeness, communication, commitment—all the things I've spent my life cowardly avoiding. But this season I found myself attending to every fold in the show's emotional fabric, every teeny stitch of its sensitive caseload. I wouldn't say I'm a convert—that would be too shaming. Oh, sure, I like Hope better with short hair, worship Nancy's pink forehead, wish that Ellen would cough up that frog in her throat, and wonder what Gary sees in Susannah, but that doesn't mean I don't have distance. Enough distance to see that thirtysomething doesn't detonate depth charges the way the first wild season of Wiseguy did or send its parodies of pop culture caroming into the side pockets like the late spoof Sledge Hammer! Even when it satirizes TV (as in an episode evoking The Dick Van Dyke Show), there's a marooned undertone of melancholy. Its hipness is a mellow slice of malaise. Every now and again, however, thirtysomething hits upon real seams of dissatisfaction and rips through into something revelatory. The foreplay is slow, the payoff considerable.

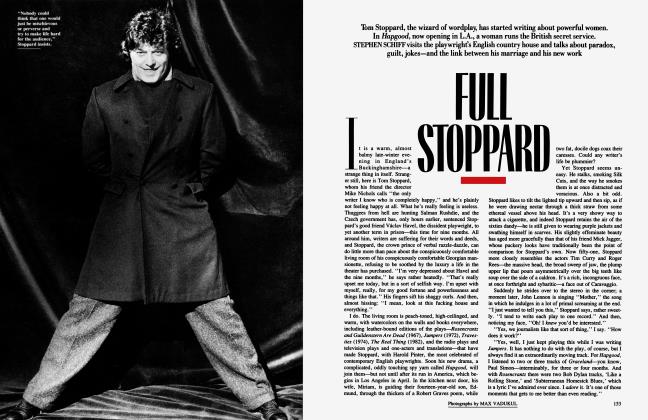

Created by Ed Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz, thirty something is shortstoryish in its arrangement of pebbles to line the pathways of its characters' lives, pop-songish in the melodic strains it picks to guide them down those paths. Probably the key song to the show is Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young's "Our House," that domestic reverie combed out of the shaggy hair of the hippie era. The cozy acoustics of "Our House" set the wistful tone for thirtysomething's warm, huddled air of sanctuary. Certainly Michael and Hope's house is one of the central characters in the show. Scenes are set in other places, but it's to the bedroom and kitchen of this dark-wood structure circa 1905 that the characters come to compare notes. (The women lie on the bed and chat like sisters at a sorority house. The sleepy weight of their bodies suggests all the hours of the afternoon.) As Michael, male head of this house, Ken Olin is a walking Y-word right down to his suspenders. But Olin is an actor who eludes cliche by maintaining something shifty in reserve. The mismatch of his eyes emblemizes the slightly distracted attention he brings to every scene. Part of him always seems to be elsewhere, harboring a fugitive idea. His wife, Hope, is all there, however, a hologram of hallowed presence. With her bowed head and bountiful smile (she always seems to be bending to embrace a child), Mel Harris's Hope is the show's eternal Madonna. If it weren't for the sly urban smile she uses to measure Michael's moods, she might come across as too sacrificing and pioneer a mother. As Manny Farber said of Liv Ullmann, she's almost more womari than the screen can bear.

Michael's best friend and business associate, Elliott (Timothy Busfield), is almost more man-boy than the screen can tolerate. Elliott wears party-guy ties (a hula girl swings her skirt on one of his favorites), snaps his fingers to summon waiters, and scratches his beard when he's feeling frisky. He's the show's cringe factor. Certainly one couldn't help but cringe when he told his blonde wife, Nancy (Patricia Wettig), that she was getting fat, or informed Michael of their prenuptial agreement: "She agreed to have two kids and to serve my every whim. I agreed to systematically destroy all her confidence and self-esteem.'' He added that this may explain why he's now living alone in a room near a neon sign blinking HOTEL HOTEL HOTEL. Elliott brings a certain essential awfulness to the show—in one episode where he was absent, the life-force seemed depleted. It's unfortunate, though, that Elliott is used as a flogged jackass in the show's ethnic jockeying. According to New York magazine, Zwick and Herskovitz are both Jewish men married to Gentile women, which may explain why thirtysomething rests on the supposition that Jewish men like Michael make stalwart husbands while nonJewish men like Elliott need a tight leash. There are times on thirtysomething when Elliott's irresponsible antics come close to making him the show's goy toy.

Yet for me a bigger cringe comes from watching the academic toy boy impersonated by Peter Horton, he of the frosted hair and golden crinkles. A harmonic convergence of the New Man that liberated women claim they want, Horton's Gary is a teacher secure in his masculinity but capable of expressing his feminine side, a creamy blend of anima and animus. He's so handy, Gary is. He builds, cooks, nurtures, and shampoos his girlfriend's frizzled, frazzled hair. He probably breast-feeds too. Mr. Gary of thirtysomething is such an enlightened, laid-back Lothario that his attraction to the bitch Susannah (Patricia Kalember) would be amusing if it transpired that he was a closet masochist—a lazy slave who enjoyed having his balls swung around like an Argentinean bola. Susannah certainly suggests a Jules Feiffer heroine looking for a strong man she can mold. But, no, Gary cleaves unto her because he hears the hurting heart beneath her chest armor. He empathizes with every skipped beat; his crinkles are concerned. Odious as Elliott is, his mefirst attitude is more reality-based and gunned for action. And Gary—Get a haircut, guy.

Every now and again thirtysomething rips through into something revelatory. The foreplay is slow, the payoff considerable.

Whatever Gary and Elliott are, they aren't "conflicted." Their fair or foul instincts are followed in a straight line. It's the secondary women on the show whose nerves run a jagged course. Michael's cousin, Melissa (Melanie Mayron), is a photographer lacking the chutzpah to close in for the cross-haired kill lens-clickers often need to succeed. She's a humanist whose photographs have poignant points to make. Mobilizing the most swollen mouth on television, Mayron telegraphs more messages with less dialogue than anyone not wearing clown face ought to be allowed. But she isn't bad when she activates her body as well as her lips— hearing good news about a photo shoot, she does a jazzy impression of Ruth Gordon, a pickled jitterbug of joy. Hope's friend Ellen (Polly Draper) is more couch-bound in her neuroses. She's the sort of defensive person to whom it is impossible to pay a compliment. When her boyfriend tells her she's beautiful, she counters, "I'm not beautiful. Hope's beautiful." Now excuse me while I go out and stick my head in a bag. But a lot of men seem to love her lived-in voice, its Demi Moore graveled drag.

Michael and Hope's house is the echo chamber for all this congested neurosis. Their walls have ears. (News of Susannah's pregnancy ricocheted off the wood.) The ingenious knack of the series is in involving us audibly in the gossip of the characters' lives while detaching us visually from the consequences. The words overheard are often overpowered by the images overseen. With every character lit as if he or she were licked by their own fireside glow, thirtysomething is a group study of skin tones, shining hair, eyelashes laden with latent intent, Significant Glances. Yet within this group portrait, the camera isolates the characters in self-absorbed space so that they often appear shelled even when they're sharing secrets. There are long silent close-ups in which they seem to retract their thoughts. No one retracts his thoughts deeper than Michael, who has the mortgage hanging over his head. A house may be a home, but it can also be a holding cell.

The most interesting development of thirty something's second season was that the solid foundation of "Our House" sank into a quagmire of outstanding loans. It began when Michael and Elliott learned that their fast track to success was muddied. Bad news hit their ad biz—corporate takeovers, client bailouts. Unable to meet the payroll, Michael and Elliott, to shift metaphors, scuttled their agency and manned the lifeboats, where they soon found themselves not only at each other's throats but at the mercy of passing creditors and possible employers. Few mercies were extended. They were forced to lean hard on their oars. One unchic chain-store executive barely made eye contact with them as they pitched their proposals. He wanted these former boy wonders to whimper and squirm. There was a spooky shot of the executive sprinkling fish food into his office aquarium as Michael cooled his heels in the background. Up against a solid wall of Schadenfreude in the workplace, Michael found the walls at home crumbling. Borderline levels of radon were detected in the house and repairs left huge holes. In an outburst of anger at Elliott (who wrote himself an unauthorized corporate-officer loan, pocketing $5,000 from the company), Michael slammed his hand into a rotting patch of plaster. The shock repercussion of his rage was reinforced by a reaction shot of his daughter Janey, jolted into tears. Olin showed his best stuff in these scenes of lost control, breathing like a man drowning in dry air.

The grand kibosh to the business union of Michael and Elliott came later, when they met at the office to clear out their belongings. Using trick effects and body doubles, the confrontation had two sets of partners pivoting around the office: Michael and Elliott as they were when they started the firm, boyish and eager; Michael and Elliott as they are today, dismantling the firm, bitter and resigned. Directed by Peter Horton (spending quality time behind the camera), it was a brilliantly choreographed square dance—the contrast between their past enthusiasm and current disaster dynamically demonstrated, the conflict in their personalities brought to the fore, the cross-talk building to an unbelievably tense din. Shouting accusations, Michael and Elliott shoved each other around, knowing neither could win. They were both losers. It was a set-to between two inmates in the house of debt.

thirtysomething chronicles a generation that filters its experiences through a scrim of old television ions.

The threat of destitution is what sent James Stewart to the rail of that bridge on a snowy eve to take the Big Out in It's a Wonderful Life. Bedford Falls, the production company for thirty something, is named after the town in It's a Wonderful Life. Unfortunately, the homage is sincere. Just as Frank Capra's Christmas classic tenderized its shredded nerves with a heavy load of angel powder (remember Clarence, trying to earn his wings?), thirty something softens its strains with cutesy touches and avoidance devices. The biggest device is the fantasy sequence. Although fantasy sequences often help vary the color and decor of episodes lumpy with laundry lint, they also become an adult form of dress-up, stressing stunt acting over character study. Capra-corny. {thirtysomething isn't the only culprit— Moonlighting's fantasies simply afford its stars bigger opportunities to mug, and there's seldom been a more useless descent into make-believe than the Wiseguy episode which brought bad-guy Sonny Steelgrave back from the great beyond so that Ken Wahl's Vinnie could confront his demons from the depths of his styling mousse.) That's what made the body check between Michael and Elliott so distinctive. Even with the visual gimmick of turning them into Doublemint twins, it was one of the rare times thirty something didn't allow its boychiks to hang commas or string italics within their sensitized thought balloons, but instead incited them to barrel ahead into confrontational theater. A week later, however, the show was back to lint collecting. My fear is that sometime in the future thirty something will send debtgnawed Michael or Elliott or both to the rail of the bridge to enact his own It's a Wonderful Life scenario. Like the babyboom generation it mirrors and chronicles, thirty something can't resist retro escape. It's the reflection of a generation most comfortable with used, wearable images. It filters its experiences through a scrim of old television ions.

thirtysomething makes the best of this blockage, this constricted sense that everything babyboomers confront in adulthood has been genetically coded by thirtysomething years of pop culture. The series accommodates thoughtful spaces between the cultural quotations. But clearly there's a need for some kind of breakout from this impasse. Zwick and Herskovitz may feel it too. As if to counter the claim that they cater only to coffee achievers, they've created a new NBC series called Dream Street (the prime mover on the project is supervising producer Mark Rosner), being shot at two-bit locales in and around Hoboken, New Jersey. Where thirty something claims the upper middle class, Dream Street stakes out the lower middle. It's lowfalutin rather than highfalutin. I asked a member of the cast if Michael and Hope might drop in at Dream Street for a visit—you know, like Bea Arthur from Golden Girls sticking her neck next door into Empty Nest. He made a face indicating they wouldn't dare. Dream Street would fry 'em on the sidewalk.

Dream Street sounds like a show A1 Bundy could watch without having to be crowbarred out of the bathroom. But concept doesn't mean a thing on TV if you don't connect with the characters, and no series has bordered upon being as interactive as thirtysomething. Scaled life-size, Hope, Michael, Elliott, and Nancy meet us at eye level. When not shying away from their thoughts, they seem to return our stares. Our dust is on their furniture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now