Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE OLD DEVIL

Kingsley Amis is creating another ruckus with his new novel, Difficulties with Girls

JAMES WOLCOTT

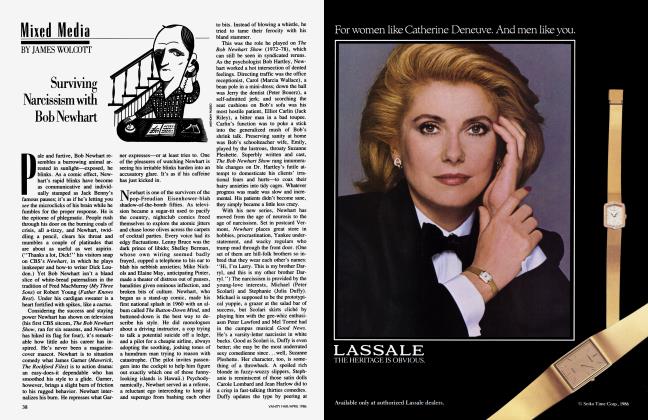

Mixed Media

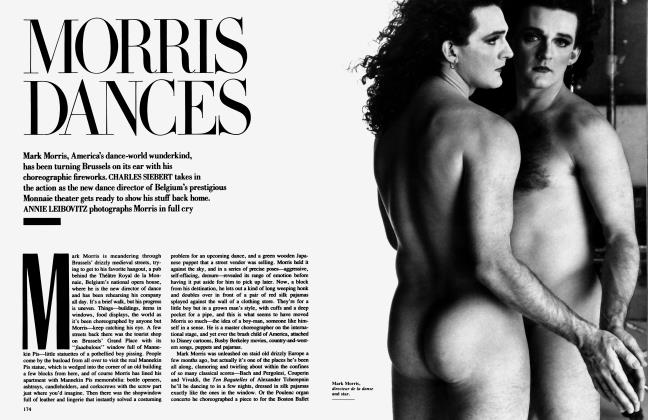

Lunchtime in London. Ambling toward the lobby of the Savoy hotel is the author Kingsley Amis. He has a recognizable stride. It's the boulevard stroll Fred Mertz had in the episode of / Love Lucy where Fred, top hat atilt, chugged into a nightclub as an English duffer, doncha know. Not that there's anything ersatz about Amis's dash or demeanor. Seated in the bar of the Savoy for a brief chat about his new novel, Difficulties with Girls (Summit), he is every stitch and seam the English gent. A portly gent, it should be said—his belt now takes a long ride around the rotunda. But his face, that of a leading man sliding into character parts, has a distinguished glaze. For someone as fond of drink as Amis is (he's written numerous books on the topic), he shows no signs of the puffy, floaty discoloration often caused by longtime submersion in the sauce. Nothing fishy about his eyes either, which are scrupulous, keen—twin sentries on alert. His eyes man their stations even as he enters a relaxation mode. Amis nurses a nonalcoholic starter called a pussyfoot, then, with a flip of his wrist to consult his watch, announces it is time for a real drink: large bourbon with ice. At the thought of having a serious gargle, he immediately perks up, like a houseguest who has heard the ding-ding of the dinner bell. Liberation is at hand.

Kingsley Amis has entered an Indian summer of acclaim. It is as if his deck chair were stationed sunward to catch the dusk. In his late sixties, Amis is mellow proof of the adage that the important thing is to outlive the bastards. With an eclectic output which includes everything from a survey of sci-fi, New Maps of Hell, to a James Bond adventure, Colonel Sun, from a study of Kipling to a roundup of his own verse, he has secured a wide berth on the shelf, but at the cost of some suspicion that slumming had stuffed his sinuses as a serious comic novelist, reducing his characters' outbursts to a chronic wheeze. The success of Stanley and the Women wounded that notion and The Old Devils dealt it a deathblow. A lopsided look at love and liquor among the Geritol set, The Old Devils won the Booker Prize in 1986.

Amis's acidic rebirth in late age has helped take the steam out of his iconoclasms as a young devil. The tempests that once swirled over Lucky Jim, Amis's status within the Angry Young Men, his championing of genre fiction and rejection of F. R. Leavis's great tradition (with characteristic overkill, Leavis supposedly reviled Amis as "a pornographer"), have been construed over time into the settled dust of academic recap. Even the boil over his political shift from Labour left to Tory right has leveled to a low simmer. He has become, in short, an institution—an underlying asset.

In a floating exchange rate where various flavors of the month are up, down, sideways, drifting, Kingsley Amis represents the gold standard in English literature, as Evelyn Waugh did before him. Like Waugh, his belly seems designed to cushion him against runs on the bank. Evidence of his asset value is a compilation of his favorite poems published in England last year called The Amis Anthology, a bedside keepsake suitable for preserving crushed rose petals. (The notes retain Amis's thorny touch, however. Apropos of a John Betjeman poem about golf, he remarks, "For the record, I am bored by golf to the point of hatred.") Although Amis appreciates the kind attention he's received in recent years, he's mildly miffed that reviewers keep treating him as a serial mugger, preying on one protected species after another. "What people tend to get wrong is this 'target' thing. 'Who is he in for this time? You know, this last time he had it in for women. This time he has it in for queers. And he has it in for. .. ' " Jews, wogs, make a list.

On that list women occupy the top spot. Despite having written sympathetically from the female point of view in the Trollopian Take a Girl Like You, Amis has acquired the reputation of behaving in print like a sour-ball S.O.B. beset by bitches. It's a somewhat dubious rap and rep. True, at the end of the labored satire Jake's Thing, his impotent Jake chooses to remain limp rather than lay himself open to women and their irrational mood mongering. And then there is Exhibit A, Stanley and the Women. After its tough go at finding a publisher in America, accusations were made that feminist cabals had sought to blockade Amis's brand of woman bashing from our beaches. But following much ado in the T.L.S. and other places, Stanley and the Women belatedly made it ashore. It remains one of Amis's most problematic novels—almost Jamesian in its implicative asides and askew point of view. When I first tried reading it, I found it thick, gray, and wrinkly, a hunk of elephant hide hacked from a lumbering attack of misogynist ego. But in a bitter funk I picked the book off the shelf, began browsing, and suddenly his warped account of dissonance between the sexes all made perfect sense. It is a novel that you don't so much read as surrender to as a chill narcotic—you have to be in a susceptible state of disappointment to receive its needle. Stanley and the Women's paranoid premise, persuasively dramatized, is that women everywhere are mad and maddening. Their unavowed aim is to make men's lives a steaming muddle. "Not enough of a motive?' ' shouts a doctor at Stanley, trying to put him wise. "Fucking up a man? Not enough of a motive? What are you talking about? Good God, you've had wives, haven't you?"

But the male bonding that takes place in Stanley (us against all them crazy dames) is a funny parody of drunken guy talk, not meant to be taken as gospel. Complaining about women is how Stanley and his chums loonily let off steam. There are worse ways to let off steam. Unlike D. H. Lawrence, whose bearded prophecies leave Amis cold, he doesn't see strife between men and women as an apocalyptic contest of will and submission—blood consciousness, phallic worship, and the eternal feminine battling it out beneath the snake-coiled tree where Eve was tempted. He veers away from absolutism and violence. He doesn't decapitate women in his fiction, like Norman Mailer, or sniff at their flesh as if it were tainted meat, like Saul Bellow and John Updike. He achieves a rough equivalence. His men are hardly prizes. The amoral shittiness of men is as constant in his fiction as the moral shiftiness of women. And those men often get their comeuppance, like the pub owner in The Green Man who stages a manage a trois only to have the two women get so entwined that he's extraneous. Amis's women certainly aren't weaklings. They have far more spike and spunk than the meek mice in Margaret Drabble and Anita Brookner. "What makes you such a howling bitch?" asks the narrator in Girl, 20 of the horrid Sylvia, who's been carrying on with his married pal, Roy. Her reply:

"I expect it's the same thing as makes you a top-heavy red-haired four-eyes who's ... impotent and likes bloody symphonies and fugues and the first variation comes before the statement of the theme and give me a decent glass of British beer and dash it all Carruthers I don't know what young people are coming to these days and a scrounger and an old woman and a failure and a hanger-on and a prig and terrified and a shower and a brisk rub-down every morning and you can't throw yourself away on a little trollop like that Roy you must think of your wife Roy old boy old boy and I'll come along but I don't say I approve and bloody dead. Please delete the items in the above that do not apply. If any."

He's mildly miffed that reviewers keep treating him as a serial mugger, preying on one protected species after another.

Any man reading such a passage will check afterward to see if he still has his scalp.

Girl, 20 is middle-period Amis. There was a tailing off of interest after that burst of verbal hostilities, into the implausible mystery of The Riverside Villas Murder (great seduction scene, though), the arthritic collapse of Ending Up, and the alternative-world fantasizing of The Alteration and Russian Hideand-Seek. Amis seemed to be in a long slough. What brought him out of his slide? It's been intimated that it was the breakup of his marriage to the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard that cracked open the raw, cathartic emotions which found their flow in Stanley and the Women. (He currently lives in a curious arrangement with his first wife and her third husband.) It may have been a healing catharsis, for his next novel, The Old Devils, had a ravishing presence named Rhiannon and a tremendously romantic ending. "The poem, his poem, was going to be the best tribute he could pay to the only woman who had ever cried for him." For his characters it's the heaviness of being that's unbearable. Lightness is for the young and the dead.

Difficulties with Girls is a drier, lighter 11 affair. It doesn't knock dentures Ir around like hockey pucks, as The Old Devils did—it wears a toothpaste smile that's yellowing at the edges. A sequel to Take a Girl Like You, Difficulties with Girls concerns the marriage of a young couple, Patrick and Jenny Standish, as they cope with the swinging sixties. They're coping better than one of their neighbors, Tim, who convinces himself after his difficulties with girls (in bed he loses his erection presto) that he's a latent case. He tries to acclimate himself to the homosexual life-style to the point of acting "poofy" at the local pub. Only a night on the town with a homosexual couple down the hall finally frightens Tim back to the straight and narrow. Amis's mild and unmalicious depiction of the gay couple has drawn a few flurries. "One reviewer, who I won't name and who's male, said the trouble with the portrayal of these males, you know, he put it like that, is that it's based on hearsay and not on actual experience. Oh, sorry about that, yeah. Hmmm. Thank you. You know, the trouble about Mr. Shakespeare's portrayal of Cleopatra, it's not based on experience."

No one disputes Amis's authority when it comes to man-woman wrangling. Perhaps the funniest exchange in Difficulties with Girls comes after a spot of adultery one afternoon. Patrick, who has just given a married woman named Wendy a spin in the sack, basks in the belief that he's thrummed her lute, uncorked an inner glow. Her hard-set look soon tells him he's quite mistaken.

"I don't understand. You drove at me so remorselessly, so.. .implacably. You seemed tormented by some kind of hatred, for me, for yourself, whatever, I don't know, I'm just baffled. What is it with you, darling? Won't you tell me, for the love of God?"

If he had not felt slightly indignant at the thought of all that good work going for nothing, he might not have said, as he did, "I know I've asked you this already, old thing, but are you absolutely sure you're not an American?"

From Lucky Jim to Sylvia's tirade in Girl, 20 to this postcoital spat in Difficulties with Girls, the best parts of his fiction have been playable—actable. Amis learned from Anthony Powell, Evelyn Waugh, and especially P. G. Wodehouse the importance of capturing character through dialogue, framing the action, keeping the staging simple. But much of his histrionics came right out of his own hammy spirit. His handsome actor's face houses big-screen lights and shadows. The poet Philip Larkin has paid tribute to Amis's pantomimic skill in their student days at Oxford, mentioning a photograph showing Amis contorting his face into a fierce scowl as he crouched on the grass with an invisible dagger, miming the role of—Japanese soldier. Even more striking than Amis's jawline jujitsu were his vocal air raids. He was a master of sound-track noises (gunfire, static, pigeons, geese) and foreign gibberish. One of his classics was a morale-boosting speech by F.D.R. fighting to be heard on a faulty radio against an incoming front of interference and band music.

Writers are often mimics, trying on attitudes like masks. But when Gore Vidal, say, imitates Richard Nixon or Ronald Reagan on TV, it's a suave simulation, a parlor trick meant to raise at most a titter. Sweat doesn't bead his marble mask. Amis's classics are more Artaud. Larkin: "Kingsley's masterpiece, which was so demanding I heard him do it only twice, involved three subalterns, a Glaswegian driver and a jeep breaking down and refusing to restart somewhere in Germany. Both times I became incapable with laughter.'' His son Martin Amis seconds the incapability part, saying that after his father's routines there isn't a dry cheek or dry pair of trousers in the house. "The great mimics are very vehement. I mean, he does one of an airplane taking off, but by the time he gets to the pilot he's completely purple in the face. Putting even his body at risk.''

I met with Martin Amis, no stranger to I vehemence himself, one night at his I home in London. "I don't have to wear nappies," one of his sons told him, "not on Tuesday I don't." Ah, the inimitable logic of children! Martin was staying with his two blond boys while his wife went out to a concert. Dinosaur toys lined a shelf downstairs. Martin himself appears in his father's fiction in I Like It Here, asking questions about big beasties. "If two tigers and a lion fought a killer whale, who would win? And him going, 'It just could never happen.' Yeah, but who would win?" He also remembers the thrill of checks arriving. "I used to run upstairs with the mail and say, 'There's a check,' and sit around and open it. It was incredibly exciting. It was a check for £700 or something, which would buy you a house." In later boyhood Martin Amis had his own literary difficulty with girls—smart and sarcastic, his first novel, The Rachel Papers, was considered a little too inclined to panty sniffing. (A somewhat sanitized version of the novel was being filmed in England when we met.) It was the addictive-minded Money (money as sex, money as maintenance, money as obsession) that put Martin on the map in America.

In his father's house his writing is still a submerged landmass, however. "He doesn't read my stuff. He can't get on with it. The last one he read, I think, was Success, thirteen years ago." His father had read a chapter of Money when it was printed in a magazine, but showed less patience with the complete novel. "I knew the exact moment he sent the novel windmilling across the room: when a minor character named Martin Amis showed up in the book. He has very firm rules about that. ' '

The amoral shiftiness of men is as constant in his fiction as the moral shiftiness of women.

Kingsley Amis resists and resents selfreferentialism in fiction not only because he thinks it's trendy but because to him its tricks are dated. "Because my first novel, which was never published, had a hero called Kingsley Amis." Its title? "The Legacy. It's a writer's title. The Legacy? Who wants to know about that?"

Writerliness Kingsley Amis abhors. To be a writerly writer is to be cerebral, cliquish, enclosed, exiled to a bookish realm, be it a Borgesian maze or a Nabokovian hall of mirrors—literary with a capital L. To be a readerly writer is to be literary, lowercase. Although Martin clearly admires his father's fiction and his dedication to book reviewing ("He believes in putting something back into literature"), he seems less enthused about the lowercase slack in the recent work. Of Difficulties with Girls, he comments, "It's sort of tacky, as if it's being told to you at a pub, that novel." For his part, Kingsley looks with amusement at his uppercase son. "My son's next novel is going to be very long—it's called London Fields. Now, that's a writer's title. That's the sort of thing that great novels are called." (The novel is also set in 1999, another sign of greatness calling.)

The tentative title of Kingsley Amis's next novel is more reader-friendly. "I think it's going to be called The Folks Who Live on the Hill. After that, you know, bloody Bing Crosby record." Only these are not Bing Crosby's idea of folks. One husband is desolated when his wife runs off with another woman— he wants her back. Another character is a woman with a history of alcoholism. "Anyway, she's off the bottle, you think she's very nice. She's going to say, 'Harry, you see those people walking on the street there?' 'Yes, dear.' 'I'd like them to be in a war.' " There are also dead-end discussions in which two baffled men try to figure out exactly what it is lesbians do. From the bits Amis recited, the book sounds like a swing back to the crust and brio of The Old Devils. He's at home with these crocodiles.

A fter The Folks Who Live on the Hill, II Kingsley Amis is considering his II memoirs, to be structured not as a chronological account of his life but as an ABC of anecdotes. "My memoirs are not going to be an autobiography, but an alphabiography, putting them in alphabetical order. Because there are only two things I have a good memory for, poetry and anecdotes. I've got lots and lots of anecdotes." As an example, he mentions the black musician Rex Stewart, cometist for eleven years in Duke Ellington's band. "I said to him, 'Did you know that King George VI'—actually, it wasn't King George VI, it was Prince George, the Duke of Kent, but I didn't know that then—'had a complete collection of Ellington records on their original American labels?' 'Yes,' he said. 'We all knew that,' he said. 'When we were refused hotel service in Charleston, somewhere like that, we'd say, "Well, George likes us. George likes us." ' "

Like the jazz masters he admires, Amis has learned to pace himself, keep his whistle wet, bend to the notes. He has a shorthand fluency, a flair for slang phrasing that's like the stop-start of fast music. Even a minor novel like Difficulties with Girls has a sad moan at the back of its metallic chimes. And there's little danger Kingsley Amis will go God on us, as Evelyn Waugh did. He's wedded to the human stew. Its incessant bubble.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now