Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

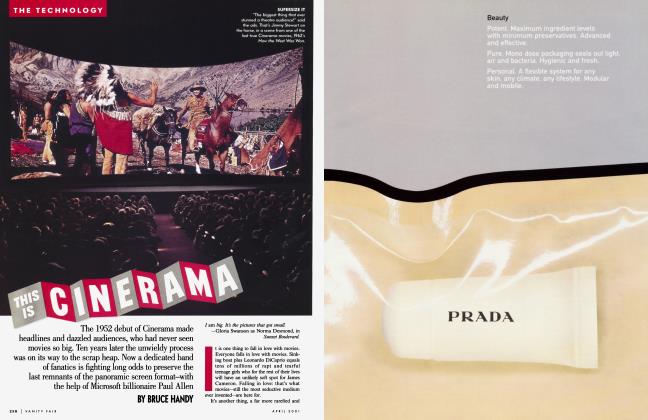

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFor four brief years, until Hollywood was throttled by the censors of the 1934 Production Code, movies told fast-paced, no-holds-barred truths. Many of the sex-and-sin-drenched classics of that gritty Depression-era spree have been exhumed-making today’s studio releases seem flabby and tame

April 2001 James WolcottFor four brief years, until Hollywood was throttled by the censors of the 1934 Production Code, movies told fast-paced, no-holds-barred truths. Many of the sex-and-sin-drenched classics of that gritty Depression-era spree have been exhumed-making today’s studio releases seem flabby and tame

April 2001 James WolcottWhat bubbles up from the past can be more inspiring and provoking—more revelatory—than the latest splash. Splashes subside; a raised Atlantis alters the landscape, heaving forgotten monuments and hidden spires into view—a phantom metropolis. The glory of movies is that their phantoms can be resurrected to walk and talk again. The last 10 years have seen an upsurge of interest, scholarship, and restoration efforts in the films of “pre-Code Hollywood,” a term covering the frisky period in the early 30s when talking pictures found their legs and spoke their piece, often with a wad of gum in their mouths. From 1930, when studios curtailed production of silent films, conceding defeat after the success of A1 Jolson’s breakthrough talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927), to 1934, when the Production Code—governing the depiction of sex, drugs, violence, and religion—began to be stiflingly enforced, the movies swung with a candor, insouciance, and pagan nudity not heard or seen again until the 60s got freaky. Prostitution, homosexuality, crooked politics, corrupt business, homegrown Fascism, child exploitation, ethnic strife, miscegenation—no topic was taboo, and many were spiked with a wisecracking humor that knocked the starch out of any editorializing. A thin crust separates posh indulgence and ragged poverty in these Depression-era films, where the stock-market crash of 1929 dogs the characters like a dark night of the soul infecting the daylight. The very gait of the actors indicates no time to spare. Everyone’s survival instincts have kicked in, keeping the films’ hustlers and daisy-faced dreamers on the nervous go. If you linger, you lose. If you stop, you might starve.

Pre-Code films connect with modern sensibilities because their expedience and strict economy fit the attention spans of Web surfers and channel clickers. Many of them clocking in at barely over an hour, these movies dash through their story lines and telegraph their messages with a no-fat delivery that makes most of today’s stuff seem bloated with narrative padding, over-calculated nuances, and fresh shipments of psychological baggage, the actors moving like slow mops. PreCode films are a reminder of what movies were before they got overly impressed with themselves and became trophy shelves for their production values and case studies for their stars. They also connect on a deeper level. Although pre-Code films are fascinating time capsules (I love the design elements: the gleaming black telephones, radios, and cars, the trim typography, the banded fedoras and suits so tight the buttons look like rivets, the women’s hats that crisscross the screen like jaunty little sails, the angel clouds of platinum hair), they hit home today because the economic jitters keeping their characters hopping rhyme with our current jitters after the dot-com bust and tech slump. (“Rolling blackouts” may become the ruling metaphor for the new millennium.) Like the characters in early 30s films, we’ve enjoyed a wild spree of sky-high prosperity, only to find ourselves facing a possible reckoning. Their protagonists not only stared into the pit, but were forced to make the descent. Pre-Code films dip their stars half in shadow, half in the beckoning light.

In the depths of the Depression, the skyscraper became a symbol of capitalism's overreaching, its hubris.

At 11:30 on the morning of 1 May 1931 [President] Hoover pressed a button in Washington and switched on the lights of a more obvious American triumph, the Empire State Building in New York.

Topped by a steel tower designed for mooring dirigibles (which were barred from the city), it was the loftiest structure on earth. New Yorkers delighted in its vital statistics: 1,250 feet high, weighing 600 million pounds, constructed with 10 million bricks, containing 67 elevators and 6,400 windows, and capable of accommodating 25,000 office workers. It had been put up in a single year at a cost of 52 million dollars....

It had also cost the lives of 48 construction workers, including one who was fired and jumped off the building.

—Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s (Knopf).

Pre-Code movies are primarily city pictures, and the symbol of the city is the skyscraper. In the Roaring Twenties, skyscrapers were cathedrals of capitalism, steel-and-concrete temples that represented ladders of success penetrating the clouds—monumental beanstalks. This phallic thrust is played for comedy in Baby Face (1933), where the harlot’s progress of its heroine—played by Barbara Stanwyck—is charted by a panning shot of the towering office building where she sleeps her way to the top. Pimped by her father at an early age, and coached by an educated crock who spouts Nietzschean proverbs, Stanwyck’s Lily decides to use her body to leave these deadbeats behind and find some real sugar daddies. The promotional tag for the film was “She played the love game with everything she had, and made ‘it’ pay.” Like Emile Zola’s Nana, the courtesan whose lower portal was said to swallow entire treasuries, Stanwyck’s Lily nearly bankrupts a major company with her sexual cunning. Phallic arrogance wilts after it’s been wrung dry.

In the depths of the Depression the skyscraper also became a symbol of capitalism’s overreaching, its hubris. In one film it served as the world’s tallest suicide diving platform. Skyscraper Souls (1932) is a classy soap opera on superstilts, set in a dream palace taller than the Empire State Building. The battle for control of the building’s ownership is a web of adultery, betrayal, and financial skulduggery that culminates in murder-suicide. After an angry mistress, Sarah (Verree Teasdale), slays her tycoon lover (played by Warren William, pre-Code’s dastardly sultan of the executive suite), she decides to join him. As Thomas Doherty writes in his excellent history Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930-1934 (Columbia University Press), “In a dreamy finale, she goes to the top of the skyscraper, her black dress billowing, and walks off into the air. In silence, without a scream, the camera watches her recede in space to the street below.” This angel of death can’t fly.

In pre-Code cinema, it’s the penthouse or the pavement, soar or splat, with no safety net in place to break an individual’s or a family’s fall. Given the absence of Social Security, unemployment insurance, food stamps, and a minimum wage, even the well-off couldn’t take their status for granted. Lives could pop like balloons—as allegorically depicted in Cecil B. DeMille’s disaster spectacle Madam Satan (1930), where a zeppelin carrying the revelers at a naughty masquerade party springs a leak, forcing the guests to parachute over Manhattan (the stockmarket crash as harlequinade)—or end up in. the gutter where they began, as demonstrated in the period’s rise-and-fall gangster epics. One of the reasons preCode gangster films such as Scarface (1932), Little Caesar (1931), and The Public Enemy (1931) hold up smartly is that they combine stark, homemade imagery—a mummy-wrapped James Cagney teetering in the doorway at the end of The Public Enemy before smacking the floor like an ironing board, the inky soup of the dangerous streets in Scarface— with drum-tight storytelling. They don’t have the self-referential mythology of the genre films that came later, since they were the original items—they supplied the references.

Where the antiheroes in crime sagas traveled a swift, brutal solo arc—from nobody to “big cheese” to Swiss cheese (it’s seldom a single bullet that brings these hoods down, but a steel hailstorm)—the reversals of fortune in the socially conscious dramas reduced rich and poor alike to humble pie. Twists of fate level the playing field, erasing class distinctions down to a common nub of humanity. Heroes for Sale (1933), the Born on the Fourth of July of the Depression era, traces the postwar travails of two soldiers from the same hometown who served alongside each other in the mucky trenches of World War I. One, Roger (Gordon Westcott), is the son of a bank president; the other, Tom (Richard Barthelmess), is a teller at the same bank. In the confusion of battle, Tom’s capture of a German officer is mistakenly credited to Roger, who drags the officer back to Allied lines after an exploding shell renders Tom unconscious. Awarded a medal for heroism, Roger returns home and is welcomed as the prodigal son, while Tom, mended by German medics and given morphine to relieve the agony of his shrapnel wounds, returns home unheralded, an addict unable to feed his habit. Even after he kicks, his life is a trail of tears—he’s Red-baited, falsely imprisoned, hounded into penury— that leads years later to the mire of a makeshift hobo camp. One of the hungry men gathered around the fire turns out to be Roger, who’s now as destitute as Tom. “The stock market crashed and we crashed with it,” he says of his father’s bank. Having come full circle since the Great War, he and Tom once again share mud and cold, only this time as brothers, bedraggled equals in the struggle to survive. The one ray of hope piercing this miasma and keeping the film from being totally grimsville is the promise of recovery offered in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s inaugural address, cited by Tom as proof that America ain’t had the stuffing knocked out of her yet.

It will come as no surprise to 30s-film buffs that Heroes for Sale was a Warner Bros, production. No MGM production would have dared cough up that much black phlegm at the powers that be. Jack L. Warner, the head of Warner Bros., was a liberal Democrat, Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM, a pious Republican, and the political differences between their studios wallpapered the screen. Warner Bros, films have the thick smudge and shout of tabloid headlines; they’re brisk, slangy, succinct, socially conscious, culturally unpretentious, ethnically diverse, and streamlined in their scenic design (letting shadows do the work instead of opening a furniture showroom on-screen). With most MGM films of the pre-Code era, it’s like being back in the Victorian parlor with the grand piano and some old aunt with a doily on her head, the walls barely able to breathe under all that bric-a-brac and coffin woodwork as the actors nobly sacrifice themselves on the altar of Beautiful Diction. There are exceptions, of course: Grand Hotel (1932) is a gleaming cocktail-shaker set come to life, and at the other extreme lurks Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), a nightmarish look at the Other that sent screening audiences racing out of the theater and still retains its shock effect, its toadstoolish influence reflected in everything from the photos of Diane Arbus to the punk anthems of the Ramones. But in almost any contest between a Warner Bros, or Paramount film and an MGM, the MGM seems duller, talkier, and overdone, dripping with class and sedated with morality. MGM romance is a sickly-sweet category, made sufferable only by grace notes such as Adrian’s gowns, or one of Clark Gable’s grins. I find it difficult to sit through most of the GaFbo vehicles for MGM without wishing that noble mare (Graham Greene’s word) would pick up the pace; her mystique has blanked and hardened into the shell of a magnificent mannequin. (As has that of Marlene Dietrich, whose performances in nonMGM exotic pre-Code comehithers such as Morocco and Shanghai Express now seem like a series of exquisitely lit still photos intended for a cultural-studies textbook on androgyny—all pose.) Aside from Dinner at Eight (1933) and Red Dust (1932), Jean Harlow—another MGM favorite—is nearly unbearable today in her sloppy, lumpy carriage and constant bleat. She’s vulgar, but not in a good way.

Pre-Code gangster films were the original items—they supplied the references.

The princess bride of pre-Code MGM was Norma Shearer, the wife of the boy-wonder producer Irving Thalbeig. Where Dietrich was often photographed as the prize exhibit in an exotic spa (a sultry oasis of feathers and palm fronds), Shearer was isolated in close-ups suitable for framing, her swan’s neck and exquisite profile offered up as a delicacy the entire nation could nibble. But once she had to relate to other actors, she didn’t know how to adjust the glow. In such films as The Divorcee (1930), for which she won an Oscar, and A Free Soul (1931), she didn’t so much emote as glisten. Her laughing eyes, valiant tears, and simpering smiles proclaim that her heroines are women who Live for Love. Adored by audiences, Shearer was a dartboard for critics who couldn’t abide her pleased-with-herself manner and primping for approval. (By the time she starred in The Women in 1939, some of them had had it. “Whether you go or not depends on whether you can stand Miss Shearer with tears flooding steadily in two directions at once,” wrote Otis Ferguson in The New Republic.) In recent years, however, there has been a lot of heavy lifting devoted to an upward revision of her reputation. Working hard to restore Shearer’s original luster is Mick LaSalle in Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood (St. Martin’s), who, after acknowledging the nay-chorus’s domination of the critical debate—“In the film book mythology that emerged, Shearer became the queenly, no-talent, cross-eyed actress_Anybody who wanted to say something nice about Shearer had to apologize first”—dubs her a “genuine pioneer.” LaSalle quotes film historian James Card, who hails her “genuine interpretive flexibility” (her what?), and calls for a popular revival: “Shearer still needs to be rediscovered by the public, in the same way that Buster Keaton and Louise Brooks, once forgotten, became twentieth-century icons.”

Adored by audiences, Norma Shearer was a dartboard for critics who couldn't abide her primping for approval.

Sympathetic as I am to underdogs, lost causes, and rainy walks on the beach, I regret to report that the Shearer diehards are worshiping the wrong goddess. After watching a succession of Shearer’s available pre-Code films, I’m afraid she’s every bit the sugary dewdrop her detractors claim, a cameo brooch of an actress who’s never going to seem contemporary despite the earnest efforts of her advocates to play up her racier films and rebrand her as a pioneer of do-me feminism. Far better candidates for enthusiastic second looks and serious rethinks are: Loretta Young, an ethereal yet embraceable ingenue whose later image as the gowned hostess of TV’s Loretta Young Show and paragon of propriety is belied by her roles as a moll in Midnight Mary (1933), an escort in Born to Be Bad (1934), and a cut-throat business executive’s cutie pie in Employees’ Entrance (1933); Jeanette MacDonald, who, before she became the yodeling partner of Nelson Eddy in a kitsch-classic series of musicals, was yummy pastry in operettas and risque comedies such as Monte Carlo (1930), One Hour with You (1932), Love Me Tonight (1932), and The Merry Widow (1934); Ruth Chatterton, who, as the boss lady in Female (1933), has her own private stud service and a love nest equipped with a buzzer system so that her staff will know which room requires cocktails; and the sensational Ann Dvorak, vibrating like a struck tuning fork as the high-strung thrill seeker in Three on a Match (1932) and Scarface (where, the critic Manny Farber wrote, her “herky-jerky cat’s meow stuff” and “aura of silly recklessness” smacked of Tender Is the Night). Nobody embodies the raw appetite and exposed wiring of women who’ve gone without and now can’t get enough better than Dvorak. Unfortunately, she didn’t have the starring roles to put her at the peak of pre-Code.

Barbara Stanwyck did. Although Stanwyck’s name and face haven’t undergone the dimming-out of her contemporaries’, even those familiar with her black-widow spider in Double Indemnity (1944), leggy fleece artist in The Lady Eve (1941), bedridden target of terror in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948), and cattle baroness in TV’s Big Valley (where the true big valley was Linda Evans’s cleavage) know only half the story. The reissue of Stanwyck’s more obscure films on video both restores her to earth and raises her to a higher pedestal. She emerges, I think, as the greatest actress of 30s film, its most incorruptible spirit and natural wonder. An actress who never reached for a false note or developed a litter of old reliables (unlike Joan Crawford, who in film after film kept gnawing on that same knuckle), Stanwyck seems almost indifferent to the luminosity of her eggshell skin, disdainful of her sexual command over dithering men as she dodges their inept lunges. Her pre-Code films are condensed pulp novels, sagas of self-preservation that shoot from naturalism to melodrama with a single glance or fallen lock of hair. Even at their most overwrought, Stanwyck refuses to let her good-bad girls writhe on a bed of nails. She hasn’t a speck of vanity or its inverse, showy masochism. Her sanity is almost saintly in its transparent purity. Her seen-it-all slouch, her righteous squalls of anger, her squint as she sizes up a fancy talker to see if he’s on the level (and the contempt that suffuses her face when someone tries to muscle her), her lunar shifts from cold detachment to beaming acceptance only the young Bette Davis, before she became too mannered, could so convincingly and transfixingly sling herself around as if obeying some inner law.

In Night Nurse (1931), an amazing piece of amoral payback directed by William Wellman (memo: any pre-Coder directed by Wellman is an automatic must-see), Stanwyck plays a nurse attending to the welfare of two children being starved to death for their trust-fund money by their dipso mother and the family’s Snidely Whiplash chauffeur, played by Clark Gable, who, dressed in a black uniform as tight as a condom, is a fascist totem of sadomasochism. Stanwyck’s transformation in Night Nurse from sullen duty to wrathful outrage is so primal it’s thrilling, and the film’s capper at the morgue is like a wicked dose of Dashiell Hammett. Ladies They Talk About (1933) sticks Stanwyck behind bars as a bank robber who refuses to rat out her associates. Trading in her glamorous Orry-Kelly outfits for what appear to be burlap sacks with armholes, Stanwyck’s Nan is given a tour of the women’s facilities at San Quentin, where she’s greeted and threatened as the “new fish”: “Listen, don’t think you can walk in here and take over this joint. There’s a lot of big sharks in here that just live on fresh fish like you,” warns Susie (Dorothy Burgess), a psycho brunette, to which Nan replies, “Yeah, when they add you up, what do you spell?” (Later, a friendlier inmate cautions, “Watch out for her, she likes to wrestle,” as the camera cuts to a lesbian dowager working a cigar.) The film’s nicest low-key moment is a curbside chat Nan has after she’s been released from prison with the detective who put her behind bars. “No hard feelings?” he asks. “No; say—you have your racket and I have mine.” “Well, so long, Nan,” he says, chuckling. “I’ll tell the boys at headquarters that you’re in circulation again, they’ll be glad to know it.” Pre-Code films had quiet interludes where even antagonists could exchange modest regards.

(Although it doesn’t qualify as pre-Code, another nifty Barbara Stanwyck unknown can’t be ignored: Internes Can’t Take Money, made in 1937. Ignore the daffy title. Superbly directed by Alfred Santell, the medical drama that introduced Dr. Kildare to the screen unfurls an early tracking shot through a heavenwhite hospital that anticipates the floating camera-eye of Orson Welles and Robert Altman and ends with a heartbreaking reunion that seems practically out of Dickens. Joel McCrea stars as the idealist with the stethoscope who helps Stanwyck find her lost child, assisted by Lloyd Nolan, giving a rousing performance as a gangster who owes the doc big-time after he patches him up without squealing to the cops. The movie’s most offbeat touch: a soft-spoken villain whose constant snacking on popcorn seems like a sinister perversion.)

The glory of movies is that their phantoms can be resurrected to walk and talk again.

The urban grit of pre-Code films became a sty in rural eyes. Resentment began to build in Middle America against all this free love and flying innuendo. That grand sham Cecil B. DeMille prophesied in 1934, “Producers are building their own funeral pyre by making films for the theater man and New York.” Too much sophistication rots the eyeballs! The main engine of this moral re-armament was the Catholic Church, whose Legion of Decency swore its members to abstain from attending “condemned” films and whose hierarchy lobbied Hollywood and Washington to weed out blasphemy and fornication and make the screen safe for peachy-keen entertainment Maw, Paw, and all the young’uns could see. The Production Code itself was a Catholic document. As Thomas Doherty writes in Pre-Code Hollywood, “The Production Code, the enabling legislation for classical Hollywood cinema, was written by Father Daniel Lord, a Jesuit priest, and Martin Quigley, a prominent Roman Catholic layman and editor of the influential exhibitors’ journal Motion Picture Herald. Their amalgam of Irish-Catholic Victorianism colors much of the cloistered design of classical Hollywood cinema, not just the warm-hearted padres played by Spencer Tracy, Pat O’Brien, and Bing Crosby, but the deeper lessons of the Baltimore catechism—deference to civil and religious authorities ... and resistance to the pleasures of the flesh in thought, word, and deed.” In the early 30s, as the movies became more graphic, American Catholics agitated for a clampdown, and Joseph I. Breen, another Catholic, was chosen to administer the Code, which he did for 20 years, debusing everything in his path. Filmmakers had to hopscotch to adapt, changing scripts, chopping scenes, and making honest women out of the brazen hussies played by Harlow, Dietrich, and Mae West. (Tough-guy actors such as Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson were able to make the transition scarcely missing a beat. As usual, it was women who incarnated temptation in the censors’ minds. Male brutality got off more lightly, as if it were just a brisk way of conducting business.)

Perhaps the greatest crime against movies wasn’t the mangling of films in the pipeline and the muffling of cinematic expression that followed, but the retroactive butchery that resulted in a desecration of Hollywood’s legacy. As Mark Vieira explains in Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood, “If the studios wanted to rerelease a film, [Breen] made them cut [objectionable] scenes—not from prints, not from fine-grain positives, not from dupe negatives—from master ‘camera’ negatives.” It was like ripping pages out of original manuscripts. Among the amputees were All Quiet on the Western Front, Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, The Public Enemy, Frankenstein, Blonde Venus, King Kong, and Tarzan and His Mate. Some of the cuts have been subsequently restored—such as the startling moment in King Kong where Kong sniffs his fingers after probing Fay Wray, and the nude underwater frolics from Tarzan and His Mate—but this doesn’t compensate for the scenes that can never be retrieved, or the complete films withdrawn from circulation or destroyed. Too much of Atlantis will remain forever submerged. Which is all the more reason for us to be grateful for the gems that have been preserved.

The most indispensable source of pre-Code material is cable’s Turner Classic Movies, which shows rare beauties not available on video and hasn’t succumbed to the dumbing-down that’s afflicted American Movie Classics. (Mick LaSalle has a helpful list in the appendix to Complicated Women of titles exclusive to TCM.) But, for the culturally disadvantaged whose cable systems don’t carry TCM, here’s a beginner’s guide to the best pre-Code discoveries, a list that excludes the widely recognized Hollywood classics made between 1930 and 1934, such as Frankenstein, King Kong, and It Happened One Night (which need no extra boost). Every one of these films is available on video and can be purchased over the Internet if your local video outlet is too overstocked with Sandra Bullock movies to carry them.

• Baby Face (1933). Nietzsche for nymphos, or the will to power travels on slim hips.

• Blessed Event (1932). Newspaper satire in the Front Page manner, but less enamored with itself and mouthing off in ways the movies soon wouldn’t dare. The radio feud between Lee Tracy, a gossip columnist with Cagney-esque brio and elastic bend, and Dick Powell, a sappy crooner who seems to be all Adam’s apple, is Jack Benny-Fred Allen hilarious.

• Bureau of Missing Persons (1933). Littleknown Bette Davis film with a vigorous Pat O’Brien on the case and a wonderful sympathy for sad sacks who drop out of society, choosing to be among the missing rather than listen to their nagging spouses.

• Employees’ Entrance (1933). The department store as mercantile hub of palace intrigue; the boss as savior-tyrant exercising his droit du seigneur over the cuties behind the counter; Warren William and Loretta Young, a doomed mating of the slick and the dewy.

• Ex-Lady (1933). In this intelligent guide to making whoopee, Bette Davis, empowered before such a word existed, plays a career woman who takes a Norma Shearer jaunt of civilized adultery.

• Female (1933). Catherine the Great in the corporate saddle, and (until the film goes soft) the amusing display of Ruth Chatterton helping herself to the same erotic perks as, oh, Warren William.

• Heroes for Sale (1933). A Woody Guthrie protest tune set to celluloid, less sepia-toned than The Grapes of Wrath.

• Night Nurse (1931). Directed by William Wellman as if he were driving through enemy fire, with a Clark Gable who would never be this elementally evil again.

Skyscraper Souls (1932). Warren William back in the executive chair and in wolf’s clothing, this time out to devour an innocent, dainty Maureen O’Sullivan, and who can blame him?

Three on a Match (1932). Bette Davis, Ann Dvorak, and Joan Blondell meeting and careening in different directions like billiard balls, with Dvorak flying right out the window in the film’s gothic finale.

When you add these films up, what do they spell? Hollywood in its wayward youth, when a social conscience wasn’t a superior attitude but an underdog defiance, when a woman was the scrappy equal of any man, and when sin still carried the tang of forbidden fruit. Since scores of pre-Code rarities remain in the vaults awaiting possible re-release, new discoveries may be in store in the years ahead. As the movies thus far saved from oblivion prove, Hollywood’s phosphorescent ghosts should not be kept in captivity. They have a lot to tell us, and they tell it as if they didn’t know how to lie.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now