Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn the expanding universe of TV makeover shows—The Swan, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, In a Fix, Nanny 911, etc.—every aspect of life, from looks and style to home and kids, can be overhauled by a manic squad of experts. But what happens when the cameras leave?

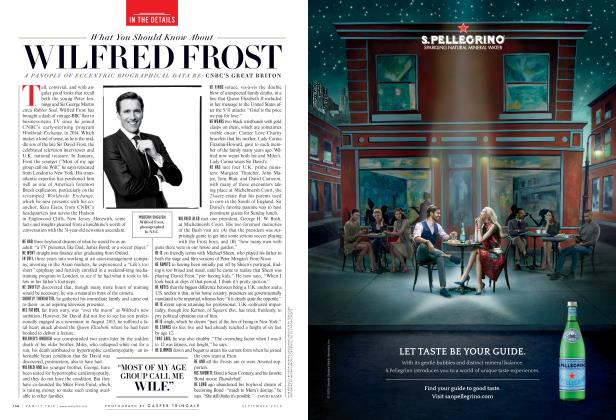

January 2005 James Wolcott Gasper Tringale, Michael ElinsIn the expanding universe of TV makeover shows—The Swan, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, In a Fix, Nanny 911, etc.—every aspect of life, from looks and style to home and kids, can be overhauled by a manic squad of experts. But what happens when the cameras leave?

January 2005 James Wolcott Gasper Tringale, Michael ElinsLook at yourself. Take a good, hard look.

Admit it, you're a mess. An unstately blob. Your hair looks as if it lost faith in itself and threw in the towel. You could at least pin it up or braid it or comb it or harvest it or something—anything would be better than looking like a dead fern. And that outfit you have on!—I wouldn't know where to begin, and neither would a police-sketch artist. It's as if you dived into a laundry chute and burrowed out the other end in maroon sweatpants and anything else you could get into. I assume the shoes you have on are comfy, because there's no other earthly justification for them, other than to nose a path through the tornado debris in that house of horrors you call home. Didn't anyone ever tell you that you're not supposed to hold the garage sale indoors? What is the archery set doing in "the study," propped up against the busted filing cabinet? How long have those peanut shells resided in the sofa cracks? Why are the kids' dirty socks draped like souvenirs all over the place? And while we're on the subject of those under-age inmates, wild beasts in Borneo have better table manners than those heathens. Look, I know it's tough managing everything alone. Sure, your husband tries to help now and then, when he's goaded and feeling guilty. "Tries"—that's the operative word. He performs a vague pantomime of Husband Trying to Help as he puts away a few dishes as if applying for sainthood. Face it, everything about your life cries out for the bulldozer.

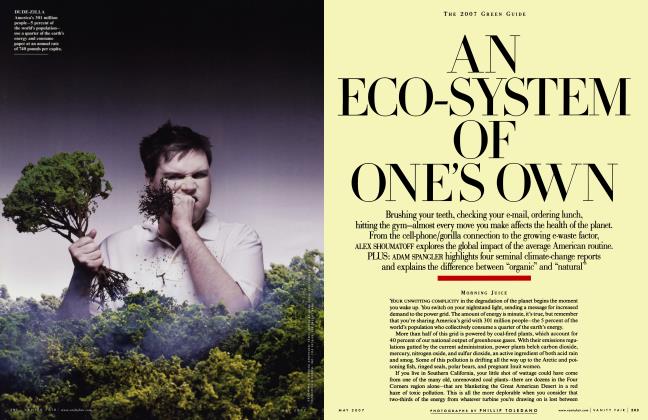

Fortunately, here in America and in our noble ally Great Britain, the caring souls who program television are able to dispatch emergency rescue squads to assist sorry cases and lazy slobs who lack the skills and wherewithal to dress themselves, beautify their dumps, tame the backyard jungle, or meet that special someone without spilling something on themselves. It's the multi-task strike force of Makeover TV.

Makeover TV treats every person, domicile, garden, wardrobe, and gas-guzzler as a rapid-reconstruction project. Parents held hostage and terrorized by their own squalling children—the spawn of Satan—can phone Fox's Nanny 911, where a no-nonsense Mary Poppins lends a firm hand to civilize the little dears. Women afflicted with weak chins, unfortunate complexions, Alley Oop eyebrows, bounceless breasts, and floor-dragging self-esteem can undergo the full Bimbo of Frankenstein spa treatment on Fox's The Swan and emerge glowing with a new face, a happening body, and a can-do attitude. Personal transformation is also the mission of ABC's Extreme Makeover, where many of the same graphic surgical procedures are employed with more humanistic tact and less someday-my-prince-will-come kitsch. If it's their wardrobes that are getting them down, women and men alike can submit to the drill-sergeanting of Susannah Constantine and Trinny Woodall on What Not to Wear (or its American counterpart), where sins against fashion are stricken from the closet. Bachelors whose apartments have all the Tuscan charm of serial-killer lairs, and whose grooming habits are the sorrow of those who come near, can put themselves in the groping hands of Carson Kressley and the gang at Bravo's Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Singles whose dates dwindle into a dying fall of awkward pauses and "the faint aroma of performing seals" (to quote Sammy Kahn) can receive sideline coaching from the Date Patrol.

And for those who need to shed an unsightly ton or two, NBC offers the edifying spectacle of The Biggest Loser, where obese contestants—divided, like Republican and Democratic states, into competing red and blue teams; tempted with sweets; tough-loved at the gym until they puke; assigned inane tasks (such as holding a bake sale)—weigh in at the end of each episode, bracing themselves for the scale's verdict while health specialists watch at home in horror. "Very humiliating," a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania told The Washington Post. "Both cruel and counterproductive," agreed the head of the New York Obesity Research Center. Experts, what do they know?

Once the individual has been reduced, repackaged, and deemed capable of being released back into society, Makeover TV can address the trouble spots in the home, apartment, or railroad shack that threaten to medley into one engulfing eyesore. Those who never tire of thumbing through shelter magazines can click from one home-makeover show to another, many of them imported or adapted from the BBC, the quality of whose original programming has been trickling downhill, sad to report. When I was able at long last to get BBC America on digital cable, I combed my hair, put on a proper shirt, and prepared for evenings of the best in news, documentaries, dramas, mini-series, and mondo-derango comedies, along with a regular dose of the rude doings on EastEnders—idiot me. Apart from immaculate conceptions such as The Office and a few O.K. forensic crime dramas, its schedule is a constant rinse cycle of Changing Rooms, Ground Force, House Invaders, House Doctor, Design Rides, and Location, Location, Location, whose jolly hosts and crews of miracle workers convert blah surroundings into bowers of bliss, banishing the tragic stigma of Hideous Wallpaper that was for so long a blot on British interiors. ("They wallpaper their ceilings!" exclaimed Paul Theroux, aghast, in The Kingdom by the Sea.) There are so many shows, so many peppy crews, that I've given up attempting to tell them apart; they're all one big tool party. This boom in gardening-decor shows has bred complaints in the British press that the trend fortifies an enclave mentality at the expense of community and civic life. One withdraws behind the sanctuary of one's mauve walls and lets everything around them go hang, but in a nice way, of course. This consumerist cocooning isn't confined to Britain. The musician Brian Eno recounts a visit in 1978 to attend the party of a rich acquaintance, the owner of a lavish, expensively done-up loft in an industrial building in an otherwise derelict, rundown section of Lower Manhattan, where winos served as the official greeters. The contrast between the squalor without and the sumptuousness within provoked Eno to ask his hostess about living on such a forbidding block. "Oh—the neighbourhood," she said. "Well... that's outside!" And outside didn't matter, barely signified. Eno diagnosed this widespread condition as retreating into the Small Here, disengaging from the Big Here of a larger neighborhood, city, country, world. Makeover TV provides the catering service in the Small Here.

Much as I try living in the Big Here, conscious of ripple effects traveling Iv I beyond my fortress study, I confess that I do favor some of the Beeb shows, and not just because I'm a TV slut who'll watch anything. I diggeth Design Rules, hosted by Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen, in part because I love the posh roll of his name, Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen. He explains and illustrates use of color, mass, and perspective with a clarity and logical progression near extinct on home-improvement shows, where jump-cut Tilt-a-Whirl effects make the simplest task—setting tiles—look like a madcap escapade. Makeover TV assumes that nobody can do anything for themselves because they lack the patience to acquire the knowledge needed to get started, that we need rush-job genius to re-assemble us (sometimes from scratch), leaving the real thinking to the pros. The letters of the cable network TLC, for example, stand for The Learning Channel. But there ain't much learning going on on The Learning Channel. The schedule is sardine-packed with makeover shows such as, well, A Makeover Story, an inspirational half-hour as generic as its title; Clean Sweep, devoted to radical declutterizing (episode synopsis: "Shelli has to overcome a couple's hoarding instincts"); In a Fix, where a sexy Mod Squad targets a house for radical improvement. If it's wacky you want, America's Ugliest Bathrooms is a Top 10 countdown of HAZMAT toilet sites that range from grim cells of gulag-green cinder blocks to indoor nature preserves of mold, mildew, and decaying moths. Only in the interests of science and this column could I bring myself to watch the TLC-style makeover shows. They're just too insistently, annoyingly cute. From the hosts to the crew members to the "real people," everyone hokes it up for the camera. The cast of In a Fix cases a house like a sheriff's unit, complete with five-star badges, before swarming into action (the jerky handheld-camera work parodying the arrests on Fox's Cops). None of these shows can resist inane banter. This is what ruined Queer Eye, which grew unwatchable when all five began competing as wisecracking cutups, trying to out-quip one another as they catalogued skid marks on skivvies, plucked pubic hairs off the toilet seat, raided the closets for funny outfits.

MAKEOVER TV TREATS EVERY PERSON, DOMICILE, GARDEN, WARDROBE, AND GAS-GUZZLER AS A RAPID-RECONSTRUCTION PROJECT.

There's another guilty reason I'm drawn to Design Rules, apart from its calm instruction. As the comedian Joy Behar iterated on The View, marriage eventually turns all men gay. By which she meant that single guys who seemed to have studied interior decoration under Ralph Kramden (the king of crummy) undergo a subtle aesthetic awakening once they turn husband. The sunflower of their mind begins to open, and a few years into the marriage finds them issuing pronouncements such as "Do you really think that lampshade picks up the green in the painting? I'm finding it a little avocado-ish in this light." I sometimes frighten myself with the vehemence with which I condemn an innocent pattern selection. I just think an Op-art bathroom is wrong.

Ali and her sons were forced onto relatives' couches and into a homeless shelter. They were all living in a cramped attic apartment when the show's producers heard of their plight and rushed to the rescue with more than $200,000 in improvements....

Ali, who has not had a bedroom to call her own in years, could not believe her eyes when she entered her bedroom suite and found it painted like a tropical paradise, with a waterfall sink in the adjoining bathroom.

—Derek Rose, New York Daily News (November 1, 2004).

In Garden Grove, Calif, the home of a 6-year-old boy with a rare brittle-bone disease was renovated with soft cork floors and curved corners. Space was created for a motherless family of eight children squeezed into a 1,200-square-foot home in Encinitas, Calif

—Felicia R. Lee, The New York Times (November 4, 2004).

On American TV, where networks never do what they can't overdo, the top makeover show is ABC's heartwarming extravaganza Extreme Makeover: Home Edition. Each week the show selects a worthy makeover candidate—a woman who works with the handicapped, a family whose daughter is allergic to the sun—and lets the expenses flow and the imaginations run riot. In the creaky dawn of daytime TV, there was a show called Queen for a Day (no one who heard it will ever forget host Jack Bailey's carnival-barker cry "Would YOU like to be QUEEN for a DAY?"), where women with hard-luck stories competed for prizes. After each told her tale of woe, the winner was judged by a studio applause meter, wrapped in an ermine-trimmed robe, and crowned. Nathanael West couldn't have devised anything more macabre. Back then the prizes were mostly useful appliances— a washer-dryer; a new refrigerator to replace the death trap rusting out in the backyard; a clean spatula. American affluence has come a long way since Formica. Simple amenities don't suffice.

On Extreme Makeover, the unveiling of the remodeled hovel is staged like a movie premiere for the shrieking delight of the excited recipients and their neighbors (who will no doubt turn bitter and envious afterward). The vehicle masking the view departs and—voila!—instant Xanadu. A pleasure palace decked out with wall-mounted plasma TV and Dolby sound, a security system with video monitors and code pads, a huge toy dinosaur specially constructed for the playroom, twin stainless-steel refrigerators, a bed that could float Cleopatra, and mini-cathedral bathrooms where the toilets flush as if whisking everything away to fairyland. Yet many of the enhancements are not hedonistic diversions. Advances in high tech have made it possible to lighten the limitations endured daily by those with disabilities: sewing tiny transmitters into the clothing of a blind, autistic child so that he can be tracked if he strays (rather than become the subject of a desperate search operation), installing an elevator for a paraplegic. The palatial dream house the residents can now call home produces a guaranteed joyous weepfest, a weekly Christmas celebration. On one Extreme Makeover, the pleasure on the beaming face of the autistic boy as he explored his customized room had everyone blubbing, including the male crew chief. I let slip a tear myself, even as I questioned some of the aesthetic choices made for the boudoir.

It's encouraging to see a show that re wards worthy people for a change, given that so much of Reality TV (of which Makeover TV is a functional offshoot) traffics in shallow, selfish, conniving—what is the noun I'm searching for?—shitheels whose very orgasms flash dollar signs. (Especially those programs predicated upon exploiting lusty greed by perpetrating fraud, such as My Big Fat Obnoxious Boss or $25 Million Dollar Hoax, where the contestants are the dupes of deception, the patsies in an elaborate prank. Such shows are further installments in the destruction of civic values by corporate media, encouraging and excusing deceit by packaging it as entertainment.) Yet Extreme Makeover: Home Edition also taps into a lottery mentality, feeding the audience's fantasy of one big score making everything right. We want it all and we want it now. Thousands of homes for working families have been built by Habitat for Humanity, but audiences are more satisfied by the sentimentalization of a single, supercharged happy ending. As government provides fewer and fewer services for its citizens, we can expect more shows that artificially fill in the gap by showing that somewhere something is being done wonderfully right.

At least with Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, there's the gratification of knowing that the quality-of-life changes will be lasting and appreciated. With most of the makeover shows, it's hard to know how long the improvements will stick. I suspect the recidivist rate for holding on to good habits and maintaining upkeep is fairly high. As with weight loss, when a lifestyle change happens too fast, the nasty rebound can be just as swift. Watching What Not to Wear with a studious eye, one develops an instinct for discerning which stylish makeover subjects will continue to make Susannah and Trinny proud, which ones will return to the sweatpants of yesteryear after the first splurge of ice cream; which dudes on Queer Eye will keep their caves neat, which brutes will let the filthy dishes fend for themselves. The fact that I've spent enough time watching these shows to develop discernment suggests I need a makeover of my own.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now