Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

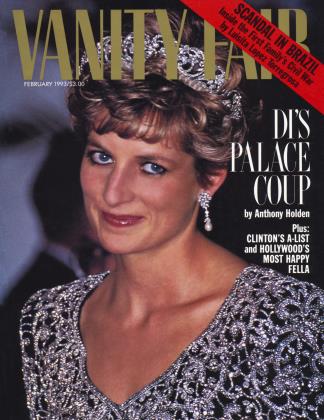

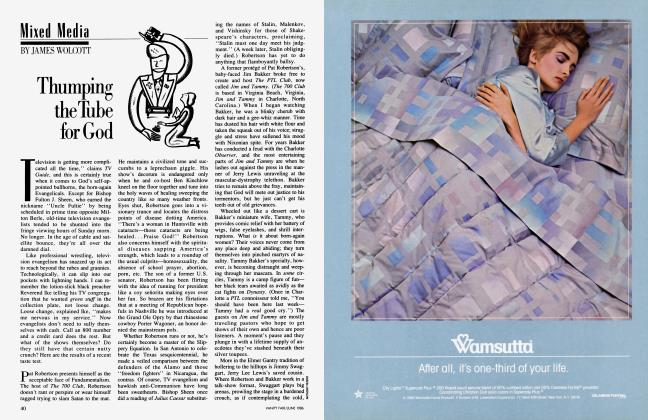

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE PRODIGAL BEAUTY

Fashion

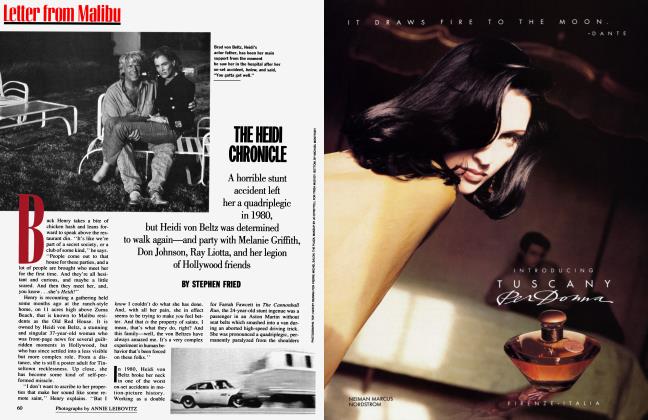

In the late 70s and early 80s, Gia was a $100,000-a-year supermodel, but a wanton life-style of drugs and partying would soon destroy her. By 1986, Gia was an anonymous welfare patient, dying of AIDS

STEPHEN FRIED

Didja ever do it for money?" asked the tall, haggard young woman, not even bothering to brush away the long hair that covered her red eyes and brokenout cheeks.

"Do what?" asked the nurse, a big-boned woman who sat cross-legged and shoeless at the opposite end of the bed—a posture she found put depressed patients at ease and made the terminal cases realize she wasn't afraid of them.

"Y'know, sex. Ever do it for money?"

"No, of course not. Why?"

"I have," said the woman, lighting a Marlboro. "I've turned a lotta tricks. For drugs, y'know. You gotta do what you gotta do."

The nurse didn't doubt the truth of the statement. The young woman's body had been violated in half a dozen ways. She had been addicted to heroin for a long time and had attempted suicide with a massive overdose only weeks before. The bruises on her upper body suggested that she had been badly beaten up. She had recently been raped. And she was suffering the effects of exposure from sleeping outdoors.

She had registered as a welfare patient in this small suburban hospital outside Philadelphia. There was a mother who came to visit sometimes, but otherwise the girl seemed very much alone. Only 26, she was one of the youngest street people the hospital had ever admitted.

"Carangi, G." had been severely depressed and mostly uncommunicative during her stay. She had been admitted first to the medical wing for treatment of pneumonia and a low white-blood-cell count. When a blood test revealed that she was H.I.V.-positive, she was placed in an isolation ward. Even though it was the summer of 1986 and health-care workers were supposed to know better, unfamiliarity with the disease was still breeding contempt. Some nurses and orderlies were donning rubber gloves or "space suits" before entering her room, and they were wiping down her phone after she used it, which only exacerbated her depression.

When the patient's medical condition stabilized, she was put on lithium and shifted to the mental-health wing. Her stepfather was too afraid of AIDS to let her come back home after discharge, and her mother, whom some hospital personnel had branded "difficult," insisted that she had no choice but to acquiesce to his wishes.

It was a pretty bleak case history that filled the files of Med. Rec. #04-3410—not many positives to reinforce. So if turning tricks for drugs was a topic that this extraordinary patient wanted to talk about, it was better than not talking at all. Or crying, which is how she had been spending many of her days. Therefore, she and the nurse talked about turning tricks and the junkie life.

Excerpted from Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia, by Stephen Fried, to be published in April by Pocket Books; ® 1993 by Stephen Marc Fried.

"You married? D'ya have any kids?'' the patient asked, to change the subject.

The nurse explained that she had a beautiful little daughter—so beautiful, in fact, that one day when they were walking through a casino in Atlantic City a photographer asked if he could take the little girl's picture. The shot appeared on the cover of a casino magazine. After that, the nurse explained, she began driving her six-year-old to New York on weekends to auditions for modeling jobs.

It was very exciting for both of them, but the daughter got few jobs and the travel expenses piled up. After a year, they stopped going, but her daughter was begging her to resume the trips.

"Don't do it," the patient said. "Even if she wants it, don't let her do it. I used to be a model. You don't want your kid to be a model."

Gia Marie Carangi knew all about mothers and daughters and modeling. Her parents had split up when she was 11, and she and her two older brothers had lived with their father, watching in disbelief as their mother quickly remarried. During her rebellious teens, which she spent "coming out" among the other gender-bent kids who snuck into Philadelphia's gay clubs and flocked to David Bowie concerts, her forays into amateur modeling for local department stores became one of the ways she could please her mother and start rebuilding their complicated relationship.

But while Gia didn't really like modeling, she was very good at it, and achingly beautiful. When she turned 18, in 1978, she went effortlessly from taking lunch orders at her father's successful hoagie shops to making international fashion statements. She became Gia, the supermodel who broke all the rules, and by 1980 her face and figure were instantly recognizable in America and Europe. She appeared on the cover of Cosmopolitan five times, as well as on the covers of American, British, French, and Italian Vogue, and she was featured in ads for Giorgio Armani, Christian Dior, and Gianni Versace. She did runway for Perry Ellis and embodied sexual fantasies for photographer Helmut Newton.

Even among the professionally beautiful, Gia was considered special. She was more the quintessential painter's model—an inspiration, "a thing of beauty"—than a working mannequin. A disproportionate number of the fashion shots she appeared in transcended commerce and approached the realm of art. But the more the camera and the people behind it fell in love with her, the more her life came undone in the fashionably dysfunctional family of the beauty industry.

Even among the professionally beautiful, Gia was considered special, more an inspiration, "a thing of beauty," than a working mannequin.

Francesco Scavullo was quite taken with Gia, who came to him a few months after having been signed by the powerful agency of former top Ford model Wilhelmina Cooper, snatched off the dance floor at Studio 54 for her first paying job by hairdresser turned photographer Ara Gallant, and launched in the Italian edition of Harper's Bazaar. It was Scavullo's job to be quite taken on a fairly regular basis, but Gia was different.

"I was mad about her," Scavullo recalled of their first sessions, in the fall of 1978. "She wasn't stylized, she didn't pose. She jumped around; you couldn't set your lights and you couldn't hold her still. 'Uch,' I said, 'this is going to be work.' But then I realized how to work with that, and I didn't want to tame her down. With most models who move around, you get bad stuff. With her, you got wonderful stuff. There is something she had... no other girl has got it. She had the perfect body for modeling: perfect eyes, mouth, hair. And, to me, the perfect attitude: 'I don't give a damn.' So she threw the clothes away, which I loved."

Gia told her mother, whose name was now Kathleen Sperr, all about that first session. "I remember the first time she went to Scavullo," Kathleen said. "A lot of times they prepare lunch for you. So Scavullo had quiche, and Gia said, 'Oh, great, that's my favorite dish. My mom makes the best quiche in the world. ' And I said, 'Gia, when somebody like Scavullo

is serving you quiche, you don't tell him that your mom's is better.' And she said, 'But it is. I don't care. Who's he?' "

Scavullo was shooting with his regular team: in-house fashion editor Sean Byrnes and two top freelancers, makeup artist Way Bandy and hairstylist Harry King. In addition to doing 12 Cosmo covers a year, Scavullo had as many Bazaar and Vogue assignments as his studio could handle, as well as major advertising accounts. Gia had a toothache the day of the session, but it still went well. Cosmo liked the pictures, and Scavullo booked her again two weeks later for another cover try. This second session was for real. The picture had a good chance of being used, and she got the standard Cosmo cover fee, which was reportedly $100.

One Friday late in October 1978, Gia's life changed. She was working with Chris Von Wangenheim, the 36-yearold dark prince of fashion photography, who had already done a number of sessions with her for Italian Bazaar. They were booked to do a studio sitting for Vogue, where she was quickly becoming the new sensation. The November issue had just come out, and it included several page-stopping pictures of her. The most stunning of these was by Arthur Elgort. Gia was posed in a Calvin Klein slip dress that was falling off one shoulder: her hair was pulled back, and, in black sunglasses, she made beautifultough for the camera. The shot was buried far back in the section, but when Vogue later put together a book on fashion history, it chose that picture as the opener for the section on 1978. It was the ultimate visualization of radical chic.

The Von Wangenheim sitting was for a fashion-and-accessory story called "Finds." There were some jackets, some tops, some skirts, and some belts. The girls posed in front of and behind a chain-link fence, on green Astroturf. Bob Fink was doing hair. The makeup artist was Sandy Linter, a beautiful blonde woman in her late 20s, who had recently become a successful freelancer after making her fame at the Manhattan salon of hairdresser Kenneth Battelle—the Kenneth who had become celebrated in the 60s for doing Jackie Kennedy's hair.

It was a very long day. Even so, when they had what they needed for Vogue, Von Wangenheim asked Gia and some of the others if they would stay around so that he could try some different shots. He generally did not like switching immediately from a commercial assignment to doing "personal stuff," but there was still a good energy left in the studio, and he had, for some time, wanted to do nude shots of Gia, uncompromised by the editorial demands of even the most liberal publications. Gia had "the best tits in the business," according to Von Wangenheim. Her figure was "unbeatable."

Von Wangenheim began with fairly tame poses—Gia covering her pubic area with both hands, her long legs crossed, her eyes glaring into the camera. Then he asked her to try jumping up onto the fence and climbing on it. "The session became amazing," recalled Sara Foley, who was then Vogue's assistant model editor. "Gia's hands were bleeding from climbing up and down. Chris worked you incredibly hard. There was literally blood coming from her hands. But she loved it, too, you see. It was three o'clock in the morning, and they were making amazing pictures."

Something else was going on as well. Gia had always been prone to crushes, and being in New York around so many beautiful women had just made things worse. During the fence session, Gia realized that she felt something for Sandy Linter, whom many in the business considered beautiful enough herself to model. Sandy and Gia had worked together before. But there was just something about the whole scene that made Gia take her own emotional pulse again.

"Years later, she could still talk about this session in such detail," recalled one friend. "She told me about the fence, and I think she said Sandy was on the fence too, on the other side. And she said, 'I looked at her, and I just fell crazy in love with her. I was listening to this music, and the more I'd jump on the fence the more excited I'd get.' She said she didn't tell Sandy about how she felt then. She didn't make a pass at her."

In early 1979, Gia went on a working cruise of the Caribbean for Glamour. The photographer was British-born John Stember. He had come to America via Paris, and his first wife, Charlie, had been one of the original Paris Elite models. Glamour was a regular client of Stember's, and he had already done a few shots of Gia for the magazine—basically cover tries and tests in his Carnegie Hall studio. This cruise was their first major trip together. "We chartered this fucking-great 85-foot yacht out of St. Vincent to go sailing for two weeks," Stember recalled. "There's eight of us: Gia and Bitten, the two models, and I've got a hairdresser, a makeup artist, a fashion editor, her assistant, myself, and my assistant. So, first day we don't get very much done, but we're all sort of getting used to it. Second day, I make a seven o'clock call, and seven comes along and we all get up, and no Gia. So eight o'clock— O.K., this is getting ridiculous. I send my assistant down to get Gia up. I get the report back from the assistant that Gia doesn't feel like getting up. So then I go down and bang on the door. 'Gia, come on, we've got a lot of work to do. The sun is good.' Finally, about nine o'clock, Gia comes up on deck in her swimming costume, and I say, 'Gia, come on, you're supposed to be ready. What the fuck are you doing? We've got 20 pages of beauty to do.'

"Her response is 'Oh, I forgot to tell you—I meant to tell you last night— I quit modeling.' I said, 'What do you mean, you quit modeling? We're out in the middle of the fucking ocean!' So I looked at the editor, and she said, 'You can't quit.' And Gia said, 'You want to fucking bet? I quit. I'm snorkeling today.' She said, 'Can you teach me how to snorkel? I might work a day if you teach me how to snorkel.' And this is what I had."

"Gia dressed street-chic way before its time," said Scavullo's fashion editor, Sean Byrnes. "And she's the one who brought that look right into Vogue'.'

While she later deigned to cooperate on some shots, Gia continued to provoke Stember and his crew. "One night we decided to play Monopoly, and I have to almost punch both of [the models] out. Gia had a knife to Bitten's throat, because she thought she was cheating and had taken one of her properties. She was prepared to kill her. It took me two days to get her to stop threatening to kill her.

"We got to Mustique, and we went to this bar called Basil's. Gia walked in, and at that time her body—she just looked so amazing, all tan and everything. She sat at the bar with her breasts kind of hanging over, and this guy by the bar—a young black guy, you know— this guy didn't know what had arrived. He was so freaked he went off on this spurt of poetic dissertation. 'You're the most beautiful thing that I've ever experienced in my entire life. Every pore of my body is alive with your beauty.' He went on like this for about 15 minutes. After he finished, I think he thought he totally swept her away with his great tirade. And she basically just turned, lifted her head up, and said, 'If I look so fucking good, why don't you get me a joint?'

"That was her response to all this poetry—all she wanted to do was get high. And then he came back with a huge pink joint, which she proceeded to smoke, and she was just totally out of it."

Many photographers would not find such behavior amusing. In fact, some were already finding Gia a chore. But Stember saw something more behind her contentiousness than another dumb, spoiled model trying to make everyone's life miserable. "I had a lot of fun times with her," he said. "But, basically, if you told Gia 'Black,' she would say 'White.' If you told her to go left, she would go right. Whatever you told her to do, she would do the opposite, and she did it to the biggest people in this business. Normally, the girls are like 'Fuck me, fuck me. I'll do anything for you.' Gia was just 'Fuck you.'

"I have never met anybody who did it in the way that she did. It was so totally self-destructive. It was the way she dealt with herself, too. But she'd put a knife to your throat if you told her that. She had this anger, you know, this tremendous anger. It took a lot of ducking and diving to put up with her. She had to see you weren't going to hit her back. I didn't need to hit her: she was doing it all for me."

At the height of the Studio 54 days, fashion illustrator Joe Eula jumped off the Halston bandwagon, fearing that if he stayed on it he would drug and drink and screw himself to death. He had blown off a lucrative promotional arrangement with American Vogue to commit full-time to Halston, and when he left the designer, whose company had become his biggest client, Eula found himself with a lot of bridges burned. Luckily, though, he was still a name to some, including Italian Bazaar, which gave him all the illustrating work he could do. Gia modeled for some of his drawings.

"We would just hole up in Italian Bazaar' s office on 78th Street for a weekend," recalled Eula. "Gia liked a little drink, you know, so we had to get ourselves motivated. We'd try some gin. When that was done, we needed some powder.

"Gia would get into poses that were extraordinary. She could hold it together—maybe because she was so stoned— for what literally could be an hour. With me, Gia didn't have to make up. She didn't have to have silk stockings on— she just had to have that leg. If it was an evening gown, all she'd really need was a pair of high heels. She could have her hair all raw or tied in a kerchief, and she could make it the most marvelous turban or whatever came out of her. We talked it. She'd get herself in the attitude, and she'd feel this great luxury. She was a true actress. She really was, in front of me, the movie actress, the star, wearing five-and-dime shit and making you think it's the greatest thing since sewing."

Gia's "look" became a presence in the business: a palpable commodity. Fashion editors and photographers referred to it when trying to tell other models what they wanted; would-be models invoked it when describing themselves. When Scavullo and Diana Ross decided to change the singer's glamorous image by slicking back her hair and dressing her down for an album cover, they thought of Gia—not the way she looked on-camera, but the way she appeared at the studio in the morning, or in the clubs at night.

"We called Gia up and said, 'Can we borrow your jeans—the ones with the hole?' " recalled Scavullo. "Those are Gia's jeans in that picture. Diana Ross said she wanted to keep them after the shooting, but Gia wouldn't let her."

"Gia dressed street-chic way before its time," said Sean Byrnes. "And she's the one who brought that look right into Vogue magazine. She just gave a modem, street-smart look to photography. She made it believable yet unbelievable. She'd wear black pants and white men's shirts and black flat pumps, or a motorcycle jacket, and, of course, the beat-up jeans. And she made it so stylish—she looked so stunning. You could put a woman in a couture gown next to her and she looked better. She was the only one to do that in modeling at that time.

"In real life a lot of models don't wear makeup, and they don't look so hot. But Gia looked beautiful with no makeup. She exuded a sexuality without trying. She was very clever, and she had a good brain. It was not easy to fool her. You know, models are models. Models are beautiful, but very seldom do they get any element of their life in the photo. They're doing it as a job, and they do it well. But Gia brought some of what she had lived into her photos, and that's what made her really special."

Denis Piel was American Vogue's hot new find for 1979, the next underappreciated photographer in his mid30s to be summoned from Paris, where he was doing magazine work. In many of Piel's most memorable shots, the models were sitting in a chair, or leaning across a sofa, or reclining on a table or floor—often with a drink nearby, since Piel was a wine connoisseur. What could be more appropriate for this go-go time, when models were so inebriated with their own success—and the inebriants that came with it—that they could barely get up in the morning? "All of a sudden Piel shows up in New York, and he's doing girls lying down ready to throw up," recalled top photographer Alex Chatelain. "I hated it at the time. Now I see it as good, but I hated him then."

For his first Paris collections for Vogue, Piel announced that his photographic innovation would be to shoot in available daylight only. Vogue ordinarily shot collections at night. Couturiers wanted the clothes during the day so that they could be sold, and Vogue editors had always stayed on New York time while in Paris—to minimize boat, and later jet, lag. Besides the daylight, Piel also wanted more than just the usual fashion props. Among other things, he required the two little boys Saint Laurent had dressed as Harlequins from Picasso paintings to give a theatrical flair to the designer's runway show.

Vogue expected Paris to be crazy, but July 1979 was complete madness—largely because legendary fashion editor Polly Mellen couldn't be there. "The situation is," recalled hairstylist John Sahag, "we're in Paris to shoot the collections. It's a big fucking deal. Everybody from New York is panicking. Denis has his own thing also. He was a little bit of an arriviste—that's what we call them. He's in a battle. He wants to shoot the clothes the way he wants them. But at the same time he's nervous about what they'll say in New York. For me, I want to be able to get another assignment, but I'm looking to score some really unbelievable-looking hair. No matter who's in my way, I'm going to do what I want to do."

After being told for the umpteenth time what was wrong with the way he had styled Gia's hair, Sahag decided to have a temper tantrum of his own. He marched Gia into the bathroom, screamed at one of the editors, "Get the fuck out of here!" and slammed the door. "Gia was on the bathroom floor, laughing hysterically," Sahag recalled. "She was just so pleased to see something like that. I was so upset. I was red. And then I started to laugh like her. She goes, 'Yeah, he's a son of a bitch.' She was trying to calm me down."

The pictures were a huge success. The stunner was a photo of Gia in a Saint Laurent lace evening dress, lying down, with the two Harlequin boys on either side, holding tight bouquets of flowers. Saint Laurent later used a version of the picture for his own book as the image that summed up the collection. American Vogue used 12 shots of Gia in all, and alternative versions of the same pictures appeared in the German edition of Vogue.

Gia made about $100,000 in 1979, and her agent, Wilhelmina, estimated that she could earn up to $500,000 in 1980. And with the all-expenses-paid travel and the free clothes, there wasn't much to spend money on, except dinners, drugs, and gifts for friends or for herself—such as a red Fiat sports car and two electric guitars, even though she didn't really know how to play. She took an apartment in a low-rise building on Fourth Avenue for $685 a month, including parking, and she lived alone.

She furnished her place sparsely. The living room was decorated with an upholstered, tigerstriped comer section from a jungletheme conversation pit (on which sat a pillow in the shape of the Frosted Flakes mascot, Tony the Tiger), a lamp in the shape of the Eiffel Tower, a massive giltframed mirror waiting to be hung, a stool covered with Fiorucci stickers, a TV, and a framed photograph of Debbie Harry. On the black smoked-glass coffee table was a small white plastic spaceship toy with a green alien sticking out. Along the wall that led to the tiny bedroom was a plastic strip full of pictures of Batman and Superman and Polaroids from recent sittings.

Except for an occasional visit from her mother—who now seemed as much a fan as a parent—Gia was increasingly isolated from the few people she actually cared about. "I would talk to her on the phone," recalled one childhood friend from Philadelphia. "We would be having these in-depth conversations, and the operator—this is before call waiting—kept beeping in, saying someone else wanted to get through, and she was saying, 'Forget it.' She would talk about how she wasn't sure if people cared about her or Gia the girl on the cover of Cosmo. Then I would call her, and she'd be very short with me: 'I'm going to England. You think it's so glamorous—it's work.' Click. That was Gia. You just never knew."

She was soon sufficiently important that taking extraordinary measures on her behalf became ordinary. "We usually just booked a backup model for any session we used Gia," recalled photographer Albert Watson. "She was beautiful enough that if she showed up it was worth doing it that way." Such a businesslike attitude was typical of Watson, the Scottish-born photographer who began his career in Los Angeles before moving to New York.

"One time I shot with Gia the entire day," Watson recalled, "and on the very end of the shooting we needed one more shot. We were outside, and there was a Hell's Angel guy on a motorbike; the guy had stopped at a traffic light, and I asked if he would be used for the shot. I wanted to put Gia on the back of the motorbike with him. She was wearing a leather outfit—Montana, I think. So he agreed, and he made about five or six passes past the camera. I went up to her and said, 'That was terrific.' She said, 'Have you got the shot?' I said yeah. She said, 'So that's it?' I said, 'That's it.' She turned to the guy and said, 'Let's go.' So, still wearing the clothes, she hopped on his bike and they just split. It took about three days to get the outfit back."

With the all-expenses-paid travel and the free clothes, there wasn't much to spend money on, except dinners, drugs, and gifts.

Watson's favorite Gia story took place in Paris at an advertising session for Saint Laurent during the haute couture. "We were shooting these dresses that were each 60, 70, 80,000 dollars," recalled Watson, "and when Gia put on the first one, she was chewing bubble gum and snapping it. There were all these ladies there from Saint Laurent to dress her. The head dresser had been with Saint Laurent since the beginning, and had been at Dior with him before. She came in, and she tied the bow on one of the black evening dresses a certain way. So Gia was kind of looking at this, chewing gum at the same time, and the first thing she did was untie the bow. She said, 'No, no, no, no, it should be more like this, ' and she retied the bow.

"Of course, the expression on this dresser's face was just incredible, with Gia retying the bow and snapping her gum. So eventually they retied it four or five times, and they agreed it was all right. So that was fine. Gia came downstairs wearing the outfit, and she saw that dinner had arrived. There was a roast chicken. So she walked over to the film table, picked up the film scissors, and went—in the Saint Laurent dress and the bow, with the makeup and the hair—and picked up the chicken, put the scissors in, and proceeded to cut the chicken in half. I must say, she didn't get anything on the dress. Then she peeled off a leg of the chicken and just ate it. When she was done, they redid the lips and she looked beautiful."

Richard Avedon was the last of the major New York fashion photographers to come around to booking Gia. Avedon, at 56, had been the most influential eye in the industry for nearly 30 years. He had been discovered and rediscovered by every client in fashion, had inspired the Hollywood musical Funny Face—had basically done it all, 9 or 10 times.

His latest project was a high-profile ad campaign for Italian designer Gianni Versace. The two men had decided that the spring 1980 campaign would employ not one but all of the top high-fashion models in New York, in groups and singles. The top male models of the day would be hired strictly as "props" for the shots. The campaign was so prestigious that the far-from-extravagant fees (for Gia, $1,250 a day) with no residuals could not be refused. Balking at the day rate meant losing one's spot in the campaign that, by design, defined who the top high-fashion girls were. They were Patti Hansen, Gia, Janice Dickinson, Rene Russo, Beverly Johnson, Kelly LeBrock, and Jerry Hall.

Gia was the central figure in many of the shots that were chosen, perhaps because she interacted best with the male models. Rene Russo sat awkwardly on one model as if he were a chair, and Patti Hansen stood a little stiffly among the unclothed men. But Gia's shots looked as if she and the guys were actually grabbing at one another, toying with one another. In several shots, she pulled the male models' hair as they held her. In another, her hand was curled inside the waistband of

the man's pants.

In January 1980, Gia took a 10-day trip to a spa in Pompano Beach, Florida, for German Vogue. John Stember was the photographer. Former Vogue fashion editor Frances Patiky Stein, who now worked for Calvin Klein but still did some freelance fashion editing, was in charge of the trip. Kim Alexis was the other model.

"Gia was with us because Frances loved Gia—the way Gia looked, that is," Stember recalled. "Frances Stein is a wonderful woman, completely mad, and great taste, best taste of anyone I've ever met, probably. But she has a low boiling point, and she will not take any shit from anybody. She just goes crazy. So this thing immediately became, like, here's Frances and here's Gia. Gia won't take any crap and Frances won't take any crap."

Gia's wake-up call for hair and makeup was six A.M. She missed it, but they were finally able to get her ready by 10:30 or so. The first shots were to be at poolside on a chaise longue. When everything was ready, Gia was brought from the shaded area where she had been made up, and carefully arranged on the chaise.

"I looked through the camera," Stember recalled, "and I was just about focused on her face when I saw her move off to the side of the frame. The next thing I heard was a splash. She was in the pool. And she just laughed. So, of course, Frances got into an outrage.

"The funniest thing of all was that, at the end of the trip, Frances was so pissed off with Gia that she decided that we were leaving without her. Gia had no money and no ticket, and we were in Florida. I had everybody in the rental van. At Frances's insistence, nobody told Gia. So we're driving away, and I see Gia running out of the front door of the hotel. Frances is saying, "Drive, drive!' And I'm saying, 'Frances, I just can't drive and leave her there.' And she's putting her foot on my foot on the accelerator. "Drive! Leave that fucking bitch,DRIVE!'

"And I said, 'No, no, no, I can't do this.' So I brake, and the next thing, the door is wrenched open. And Gia knows it's not me, it's Frances. So the two of them are rolling out of the van, punching each other. They literally got into a fistfight. But this was Gia."

"She couldn't satisfy herself... and she was very, very aggressive. You couldn't room her with another girl, If you did, she made advances."

On February 5, 1980, a week after her 20th birthday, Gia flew to the Caribbean for a Vogue shoot with Scavullo and fashion editor Polly Mellen. On the boat ride from St. Martin to St. Barts, Harry King snapped pictures of Way Bandy and the models: Gia, Kim Alexis, and Jeff Aquilon. Everybody was very relaxed until Sean Byrnes found something that had dropped out of Gia's bag. "She dropped her drugs, and I found them and threw them overboard," Byrnes recalled. "And she got hysterical. Gia didn't know that I did it, and at first she was ready to leave. I thought it was coke, but it wasn't."

Polly Mellen saw that there were going to be behind-the-scenes problems with the trip. But she also saw how beautifully the pictures were going, and how well Gia worked with Scavullo, Bandy, and King. "I don't consider whether a girl is difficult or not difficult," Mellen recalled. "If she's good, I work with the difficulty. Gia was very vulnerable; it was part of the beauty of her photographs. She gave you back something wonderful. There's never been anyone that had what she had. And she was just at the right time. She had that boy/girl thing, and it was sexy—it was everything.

"Gia had a very brilliant future in modeling. And that isn't true of every girl who gets into Vogue. Some models will never make it, they just aren't bigtime, but they can work for a certain picture, a certain situation, and then that situation passes. But that wasn't Gia's situation. Gia was really dynamite. . . even though she was really sick in a lot of ways. I knew her background was difficult, but I didn't know she was a lesbian for a long time, until the St. Barts trip. And it was really a problem. In other words, she couldn't satisfy herself. . . and she was very, very aggressive. You couldn't room her with another girl. If you did, she made advances, and the other girls would come and speak to me. You had to keep her away from other beautiful girls, and you had to watch her very carefully if she went out at night—if you were going to see her again the next day."

Gia had used recreational drugs since her early teens, and, as a model, graduated from Quaaludes to whatever pills and powders were available at the high end of highs—even snorting heroin, which had become fashionable. But after Wilhelmina, her adored agent and protector, died on March 1, 1980, Gia started using heroin more regularly and showing up for work on time even less regularly than usual. Soon she was skipping bookings altogether. Or showing up high. Or shooting up in the bathroom during sessions. She was booked to go to the Italian collections over the July 4 weekend. She took a cab to Kennedy Airport, saw that there was only a one-way ticket waiting for her, and decided there was something wrong with the booking. So she turned around and took a cab home, vowing to get all her financial affairs at Wilhelmina in order so that she could switch agencies.

"I called Wilhelmina's and told them what happened," she wrote in her datebook. "They thought I should have went . . .it seemed like a strange deal. Everyone at the agency kept saying I was to be paid $5,000, which is the right price for the trip. But at the end I would get $3,000.

"I don't know what is happening in my life, nothing seems or feels right to me. I want to live so bad. But I'm so terribly sad. I wish Wilhelmina didn't die. She was so wonderful to talk to about work. I cry every day for a little while. I wish I knew what to do. I almost bought a beautiful cat today. But it had ringworm. I pray that things fall into place."

Three days later, Gia was on the cover of American Vogue. She had been on the cover of Cosmo the previous month, and was also on the cover of the current French Vogue. But the cover of American Vogue was the Carnegie Hall of modeling. Vogue was still willing to give her work even though she had pulled the ultimate stunt, creating one of the fastest-traveling anecdotes in the history of fashion: she had walked out on Avedon.

"She used to tell me that story herself. She thought it was great," recalled John Stember. "She went to do a cover for Vogue. They did all the hair and makeup and spent all those fucking hours getting her ready and getting her dressed, and the editor was flitting around saying, 'Wonderful, wonderful, she's the most gorgeous thing in the world,' screaming at the assistants, you know. So Avedon goes click. One click. And Gia says, 'Hold on a second, I've got to go to the bathroom. ' So she goes to the bathroom to have a pee. She climbs out the window, gets in a cab, and goes home."

Even after that, Gia continued working for Vogue. She managed to stay off drugs for several weeks—at least during working hours—and did sittings with Denis Piel, Chris Von Wangenheim, and Arthur Elgort. Then Vogue sent her on a weeklong trip to Southampton, Long Island, where Scavullo had a house. Harry King was doing hair, Sandy Linter makeup. Instead of going with the others, Gia insisted on driving her own car out.

Vogue was hoping for a replay of Gia and Scavullo's highly successful trip to St. Barts. Instead, the trip turned out to be a nightmare. ''Gia would drive off," recalled Harry King. "We assumed she was looking for drugs." They also assumed that she found drugs, and, when the pictures were finally delivered to Vogue, so did the magazine's fashion department. In a number of the shots, which were of bathing suits and summerwear, there were visible red bumps in the crooks of her elbows—tracks. "I remember when those pictures came in," said Sara Foley, "there was a big scene in the art department." The pictures were airbrushed to minimize the obvious, but needle marks were visible in the November 1980 issue.

Gia did one more major sitting for Vogue, the day she returned from Southampton, with Denis Piel and Polly Mellen. The shot that ran, a beauty picture for an article on "the fragrance collections," was one of Piel's best, a seemingly stolen moment of Gia sitting in a wooden chair, tugging at the front of her spaghetti-strap dress, and peering down at herself. After that, it became clear that she could not go on—or that she had at last violated even Vogue's standards for indulgence.

Vogue was willing to give her work even though she had pulled the ultimate stunt: she had walked out on Avedon.

"At one shoot, she had fallen asleep and we had to wait and leave her in the chair until she woke up," recalled Polly Mellen. "And this other time—it was shocking, this incident. We were shooting her in a very bare dress and the photographer said, 'Polly, could you come here and look through the camera. ' And there was blood coming down her arm, from where she injected herself while we were shooting. ' '

There were, of course, plenty of other clients besides Vogue. Two days after her Vogue session, Gia had a morning screen test for Peter Bogdanovich's new film, which she missed because of a Perry Ellis fitting and another catalogue shoot. Later the same day, she went to Scavullo's studio to be interviewed for Scavullo Women, the coffee-table beauty book he and Sean Byrnes were preparing for publication in 1982. And in the evening she met with director Franco Zeffirelli, who also wanted to see her about a film. Several days later she took a late-afternoon flight from New York to Los Angeles, did a four-and-ahalf-hour lingerie sitting, earning $1,575, and caught the red-eye back to New York.

But eventually the drugs and the gossip caught up with her. The work began to dry up, and her professional friends fled for their own lives. "You know, there are hardly any girls who disappear when they're reaching their height," said Scavullo. "They usually stay around until you can't photograph them any longer. There were lots of girls who were victims of those times—the nightlife, Studio 54, dancing, having fun. There were girls who took a lot of coke and destroyed their beauty. But I don't think Gia was one of those. I think she was a victim of herself. . . . She was too smart for the world she had come into. I don't mean the fashion world. I mean this world."

In the winter of 1980-81, Gia left New York to try to clean up from the drugs— which she had taken to buying, in massive quantities with cash carried in her shoe, at the heroin supermarket set up in decrepit buildings on the Lower East Side. But even in semi-retirement she didn't stop generating horror stories. Just after midnight on Sunday, March 22, a suburban-Philadelphia police officer in a marked jeep saw a little red sports car come barreling down a divided, tree-lined street. The car collided with the dead-end fence, backed up, jumped the traffic island, and zoomed off. The officer turned on his siren and began a high-speed chase. He finally pulled even with the sports car and tried to force it off the road. The driver instead turned toward him and started playing bumper cars. By that time, other officers had come from the opposite direction and blocked off the next intersection. Gia was taken into custody.

The arrest was just the beginning of a nightmarish period at "the Hacienda"— the name Gia's friends had given to the Spanish-style house in one of Philadelphia's northern suburbs where Gia's mother and stepfather lived and Gia had a bedroom. In early June, Kathleen Sperr and her husband came back from a short trip to Bloomington, Indiana, and found every surface in the house covered with a thin layer of soot. "Gia almost burned the house down," Kathleen said. "She put something in the fireplace and didn't open the flue, and then she fell asleep because she was so high on heroin. I screamed for about three days."

Gia had also developed a frightening abscess on the top of her hand—an actual tunnel leading directly into her bloodstream. "At that time, her hand started getting really infected, because she was shooting into it," Kathleen said. "How she ever kept that arm, I don't know. The infection was absolutely horrible. I said, 'Gia, if you die, people will say to me, Where were you?'

Gia spent the summer trying to kick drugs and periodically taking modeling jobs. She was based in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and occasionally went down to Atlantic City. Her brothers and father now lived permanently at the shore, only 90 miles away, but far enough that they weren't much a part of her day-to-day life. In fact, as they opened two more hoagie shops they were only vaguely aware of how bad her drug problem had become.

Early one morning—about five o'clock—Kathleen woke up with a premonition and took a look at her well-hidden stash of jewelry. When she checked, she saw that much of it was gone. Kathleen banged on her daughter's bedroom door, and Gia hurriedly gathered together a few things and sprinted out of the house. It was days before she called to let anyone know where she was.

Kathleen went to the local magistrate in Bucks County to swear out a criminal complaint against Gia. She hoped that an arrest, another arrest, might be a way to force her into rehabilitation. "I wanted to get her committed," Kathleen recalled, ''but because of her age and the fact that she was out of my household, I could have gone through the legal process and spent all this money and she could still be out on the street again in 24 hours." The judge issued the warrant, but Gia was never actively pursued.

In late 1981, Gia signed with Elite— after leaving what was left of the Wilhelmina agency, and creating brief unpleasantnesses at Ford and Legends. She took her place among the stars in the agency's January 1982 book: Carol Alt, Andie (MacDowell), Bitten, Kim Charlton, Janice and Debbie Dickinson, Kelly Emberg, Iman, Lena Kansbod, Paulina (Porizkova), Phoebe (Cates), Joan Severance, and Tara Shannon.

Gia was determined to remake a name for herself in modeling. She was met in New York by both the people who had never succumbed to the drug and drinking culture and those who had already reached their own personal bottoms. It was hardest for the models to come back. Their contacts and track records were significant, but too much experience could reinforce the easily formed impression that a girl was past her prime. When Gia went to see former Vogue model editor Sara Foley—who had taken a life-style sabbatical herself and re-emerged in the agency of photographer Patrick Demarchelier's rep, Bryan Bantry—the old pictures in her new Elite book only reminded the agent how amazing one of her favorite models used to look.

"I remember when Gia tried to make a comeback she used to carry that nude behind the fence around in her portfolio," said Foley, "and she was so proud of it." (Chris Von Wangenheim, who had taken the picture, had been planning a comeback of his own—after a period of decline caused by drugs and the emotional strain of his impending divorce— before dying in a single-car crash on St. Martin the previous spring.)

One of her first jobs after returning to active duty was generously provided by Scavullo. He agreed to give her a Cosmo cover try. "He did that because he was a very kind man and he felt sorry for her," recalled Harry King. "Scavullo had had people very close to him be involved with drugs before."

She was shot stuffed into a strapless Fabrice party dress, her hands tucked beneath her. Way Bandy did the best he could with Gia's makeup; Harry King did the same with her hair. The camera angle was meant to minimize the bloating caused by the methadone and the weight gain from the sweets junkies often crave. The pose was designed to conceal the gory abscess on her hand, about which she still hadn't seen a doctor. "That thing on her hand" quickly became an industry metaphor for what Gia had done to herself. It was a selfinflicted stigma that she continually picked open, like a child unable to keep her hands off a scab on a scraped knee.

"That thing on her hand" quickly became an industry metaphor for what Gia had done to herself. It was a self-inflicted stigma.

Scavullo persuaded Cosmo to use the shot of Gia for the cover of the April 1982 issue. She was also interviewed for the magazine's "This Month's Cosmo Cover Girl" feature. Gia told the interviewer that she envisioned herself in "a job where I can be out of the limelight making things happen, possibly cinematography. Modeling is a short gig—unless you want to be jumping out of washing machines when you're thirty!"

The cover photo itself suggested that she would be wise to begin laying the groundwork quickly for that next career. "What she was doing to herself finally showed in the pictures," recalled Sean Byrnes. "It was kind of sad. We got her on the cover, but I could see the change in her beauty. There was an emptiness in her eyes."

For the next few years, Gia was in and out of rehab units and methadone programs, where some of her counselors considered her dwindling modeling jobs a rarefied form of prostitution— since she was working only to make money for drugs. She lived with her lover, Rochelle Rosen (not her real name), in Philadelphia and later Atlantic City, and waitressed sporadically between the occasional assignments from German catalogue clients, who were happy to get a model of Gia's stature, no matter how washed-up. In 1985, Gia finally checked herself into an inpatient drug program for indigent addicts and spent six months cleaning up. She stayed clean for several months afterward, and was even thinking of returning to modeling in the new year.

A lot of the top models she had reigned with had either been elevated to the newly created status of "supermodel" or disappeared into good marriages, bad drug habits, or both. Many of the top models didn't seem that interested in modeling anymore: Kelly Emberg had all but given up her career to cohabit with singer Rod Stewart, Patti Hansen had been in a few bad movies before marrying Keith Richards and becoming a full-time mother, and Christie Brinkley was beginning her very public romance with Billy Joel, as was Carol Alt with hockey star Ron Greschner. Since 1980, Cheryl Tiegs had been designing sportswear for Sears.

Some of the top girls hadn't landed quite so softly. Esme Marshall, who had once set off a major war when she decided to change agencies, was destroyed by what some in the industry believed was drugs but what she would later explain was an abusive relationship with her boyfriend. Lisa Taylor—the model in many of Helmut Newton's and Chris Von Wangenheim's most memorable shots of the mid-70s—went public about why her career was in shambles, destroyed by substance abuse and what she said was a selfdestructive relationship with actor Tommy Lee Jones, whom she had met during the filming of Eyes of Laura Mars. Taylor said that cocaine was a major culprit: it made her paranoid and she would often be sitting in her apartment all alone when "suddenly I'd think that there were 5,000 people standing around me trying to take my picture. I'd actually look around to see if they were there.''

Janice Dickinson was still working, but she had been through a lot of weirdness. She was having drug problems, for which she would eventually enter rehab. She also veered into what fellow fashionistas referred to as "Janice's nude period," when she began posing naked even when she wasn't asked to.

"Many of these models have a very big sex problem," said Monique Pillard, of the Elite agency. "They are made like the goddesses of the world. I mean, oh, my God, can you imagine? And all of a sudden they have hang-ups about themselves, very anti-men hang-ups, and what happens is they go crazy half of the time, because they don't feel intimately at home within themselves. They're afraid they can't perform as the picture makes them [appear to] perform. ... You get these girls who look wow, you know. And this girl feels thoroughly inadequate in her private intimate life."

As the modeling industry expanded, it needed as many of its elder statesgirls in place as possible. The agencies needed Christie Brinkley to attract the next crop of girls who wanted to be Christie Brinkley. The cresting model of the moment was 20-year-old Paulina Porizkova, who had been an Elite model since her mid-teens. When her Sports Illustrated covers and rock-video appearances brought her mass recognition, she began going on talk shows and proclaiming, in heavily accented English, that modeling was boring and she hated it, but that she was making a lot of money. The kvetching only increased her celebrity status. Paulina was showing the same healthy disrespect for the industry that Gia had been famous for: the difference was that Paulina showed up for her jobs.

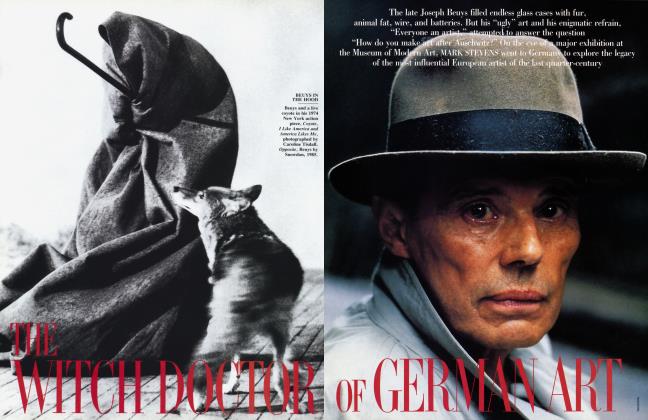

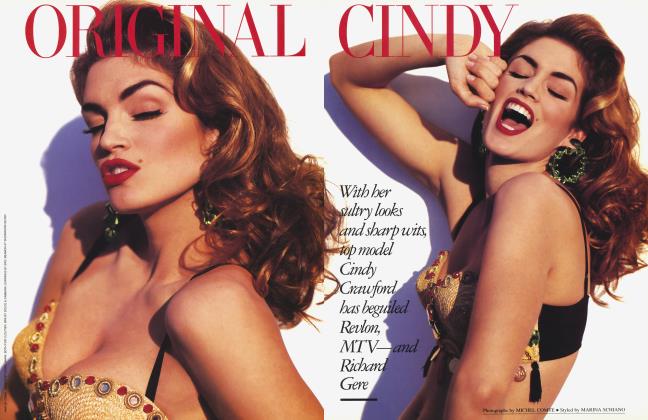

Demand for Gia's "look" remained so high that Elite was bringing a rising model with similarly dark features and a full figure from its Chicago office to New York. Cindy Crawford, a 19-year-old former Northwestern undergrad, was quickly nicknamed "Baby Gia" in the modeling business, and she developed a reputation for delivering something close to "the look," but without all the aggravation.

In early 1986, Gia became convinced that she had AIDS. The fashion industry had been quietly noting for a year or two that a lot of the young, partying kids it counted on for influxes of raw energy were disappearing with greater regularity. In this image-conscious business, homosexuality, long associated with a higher fashion sense, was now associated with the plague. Makeup artists and hairdressers, who had once regaled models in the mornings with stories of sexual exploits, now found it prudent to announce their monogamy, or even celibacy.

Gia tried to tell her mother that she was ill, but Kathleen didn't believe her. "On Memorial Day, she came to me and said, 'Mommy, I really have something wrong with me,' " Sperr said. "You could tell she was disturbed. And it still bothers me that I just went ahead about my business. I was working at Spiegel then, and I just went to work. But that's what you would have done—she didn't seem any different."

Gia went to her brother Michael's place in Atlantic City, to get all her things together. Then she pawned every thing she could get her hands on. She also sold her Fiat, for a bargain $1,700. She spent all the money—well over $2,000— on heroin and checked into a cheap hotel. She did her best to overdose, but was unsuccessful. She stayed in the room for a couple of days, and finally snuck into Rochelle's apartment in Margate.

Rochelle, whose relationship with Gia remained sporadic, hadn't heard from her for about a week. "I came home from work and went in the apartment," she recalled. "I had my friend Steven staying with me, and I laid down, and I heard breathing. I told him, 'There's somebody in this room.' He's a cute little gay guy—he put his hand on his hip and said, 'There's nobody in here.' Then I heard a cough. I looked, and Gia was under the bed. She crawled out, and I said, 'What are you doing here?' She said, 'I'm sleeping. I'm sick. I don't feel good. I don't have anywhere to go.'

"I cleaned her up with a washcloth. At that time she said, 'I think I have AIDS.' She didn't look good, but AIDS wasn't really around yet. And Gia always had dark circles under her eyes. She just looked like she had been on a drug binge. And I thought she was telling me she had AIDS as one of her things to make me feel sorry for her. Finally I said she could spend the night. In the morning, she said she was going to get something for breakfast. I asked if she needed money. She said, 'No, stay here.' What I didn't know was that she had already taken all my tip money from my jeans, and she went off to buy drugs. So I sat in the living room and waited for her. I was so pissed.

"She came back about two in the afternoon, when she thought it was safe and I was at work. She still had her key. She thought she was just going to hang out at the house. And she walked in, and I was fighting her to get into her pockets to find her dope, and that's when we were just pushing and shoving and all that. We threw each other around. And she was trying to run out the door, and I grabbed the shirt off of her so she wouldn't run out. I pulled it off her, and she ran out the door like that. I called the police on her: I wanted her brought home.

"The next thing I heard she was in the hospital in Philadelphia and she had pneumonia."

From the beginning of Gia's second hospital stay, in the fall of 1986, Kathleen took complete control of her daughter's life. She decided who could be told about Gia's condition, and what. Although Gia had been quite open about her diagnosis of AIDS-related complex several months before, Kathleen was now insisting that she had been hospitalized for "female problems." When old friends called, Kathleen could not bring herself to admit to them that Gia was terminally ill. Besides the personal stigma attached to such an admission, she was afraid that the local press—which had never even reported on Gia's drug problems—might get ahold of the story. Gia's good friend Way Bandy had died of AIDS several weeks before—very publicly, with full disclosure to the press.

Kathleen kept Gia's friends from visiting her, and later couldn't bring herself to go through with plans to avoid putting her daughter on life-support. Gia ended up on a respirator for nearly a month. Her room was decorated with flowers—Kathleen was surprised the hospital would allow flowers in such a sterile environment, but when she found out it was O.K. she filled the room with yellow roses, Gia's favorite. There were also a few toys: a stuffed monkey and a yellow butterfly that Rob Fay, one of her closest friends from rehab, had hung from the IV holder above her.

Dawn Phillips, whom Gia had also met in rehab (and had lived with briefly in Norristown, Pennsylvania, after her diagnosis, until her stepfather got over his fear of having her in the house), managed to sneak in to see her only once, and found her restrained so that she wouldn't pull the tubes out of her body. The nurse undid the restraint, and Gia took Dawn by the shoulder and tried to pull her close.

"She was pulling my face towards her and trying to say something," Dawn recalled, "but with the tube in her mouth, she couldn't. No one else was in the room, and I began to get frightened. I didn't want to react to being so close to her... yet there was fresh blood and saliva coming from her mouth. The whole time I was fighting my tears. When I got to the waiting room, I walked by Gia's mom and Rob, who were there speaking. . . . When I went over to talk to them, Kathy was saying we weren't supposed to be there. I said, 'Don't you think Gia needs to know she has friends who care about and love her, too?' "

The 19-year-old Cindy Crawford was quickly nicknamed "Baby Gia" for delivering something close to "the look," but without all the aggravation.

A few of the nurses gave Gia lots of extra attention. "There was one girl who would take care of her like a young child," Kathleen recalled. "She got to know Gia the way I knew Gia. She would comb Gia's hair, get her all fixed up. I took in ribbons. Gia didn't like ribbons, and she would take the ribbons out. Then they would tie her hair up with a piece of hospital string, and she was satisfied with that." Gia didn't want her mother to look at her atrophying extremities. "Her nightgown would get pulled up, and she didn't want me to see her," she said. "Gia would force the nightgown down, and it was amazing that someone on a respirator would still have that pride."

The last holiday mother and daughter celebrated together was Halloween. "She had pumpkins in the room," Kathleen said, crying. "I went out at lunchtime and brought her a great big scary hand and some little cat. And I laid the cat on her head and put the scary hand on her. When the doctor came in, I said, 'You have to show him your Halloween outfit.' And she reached over with the hand and pretended like she was scary. He couldn't believe that we celebrated Halloween."

'She died around 10 in the morning," Kathleen recalled. "I saw them wash her, and the flesh fell off her back. I had my Bible with me. Usually when Gia went anyplace, she took her Bible with her, but she made me leave hers at home so it wouldn't get messed up or lost or something. I hadn't read it all day. I had just left her father in the waiting room. I was reading her the 23rd Psalm—'The Lord is my shepherd.' I had read it through once, and I started again, and I got to 'the valley of the shadow of death.' And I saw something out of the corner of my eye. I looked up, and the nurse that was on duty was running out of the room, and the machines were going haywire.

"I ran to her and sobbed, 'Oh, my baby, my baby,' and she was gone. They took all the hoses out of her. It was over. Luckily, the first undertaker we went to had no objections to preparing an AIDS patient. He just encouraged us to keep it a little quieter than we wanted to—suggested we not do an obituary in New York. He said we should have a closed casket, because he didn't know how she would look. But I did have to pick out what she would wear anyway. He suggested a dressing gown and nice lounging pajamas—to make sure it was big and roomy.

"Her father walked in and saw it was a closed casket and had a fit. But Gia and I had a pact that if she wasn't going to look her absolute best it should be a closed casket. She didn't want people looking at her if she didn't look good."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now