Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMACHO, MACHO McGUANE

In his new novel, Nothing but Blue Skies, Tom McGuane further plumbs the collective psyche of the cojones-and-Coors crowd

JAMES WOLCOTT

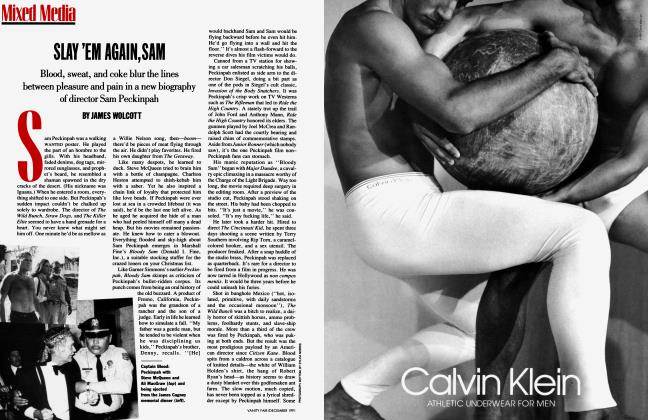

Mixed Media

Montana has become modem American lit's magnetic north. Its cluster of celebrity talent has made it the Bloomsbury of the Snowbelt. On its Main Streets fresh-faced authors step off the bus in the hope of becoming wind-creased witnesses to the last dying breath of untamed wilderness. What relief! No more Gordon Lish minimalist potty training. No more zombie strolls through the shopping mall to catalogue suburbia's tacky materialism. The prospects for prose are panoramic. Here epics await, written in rock. Situated in Big Sky country between the sissy East and the flaky West, Montana is a state where men are men and the livestock are nervous. "God made women because sheep can't cook," goes a wisecrack in one local novel. Although women writers have cleared some elbowroom (Missoula hosts the Rattlesnake Ladies Salon), Montana is mostly a male hangout, hitching post to such notables as Rick Bass, Rick DeMarinis, Russell Chatham, Tim Cahill, William Kittredge, William Hjortsberg, James Crumley, Ivan Doig, and James Welch. It's never

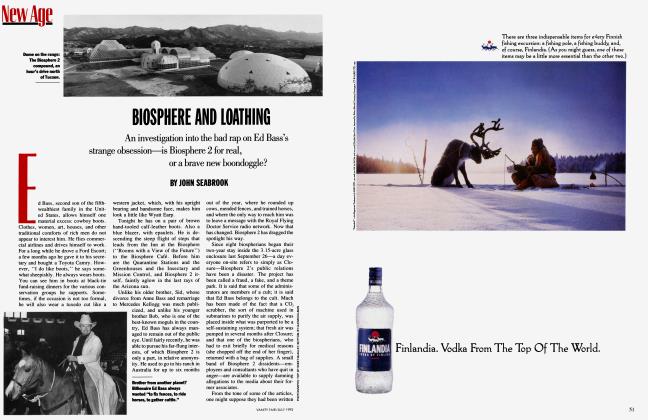

hard rounding up a posse. But of all these rootin'tootin' writer fellers, none rides taller in the saddle than Thomas McGuane. A novelist, screenwriter, director, and sportsman, the six-foot-three McGuane is a macho totem with hip flair—Hemingway with styling mousse. In photographs he's as handsome as a silver dollar. (He leaned on the bar like a Marlboro man in Cold Feet, a movie he co-wrote with Jim Harrison.) After the ricochet brilliance of his early novels The Sporting Club and Ninety-two in the Shade, he attracted a Hollywood set of Hawaiian-shirt party hearties who sunned themselves like alligators down in Key West between debauches. His relations with actresses such as Margot Kidder and Elizabeth Ashley made him the sex symbol of English majors everywhere. All this hula dancing at dawn took a toll. His writing became so smug and elliptical that he seemed to be murmuring sweet nothings into a microphone tucked in his sleeve rather than writing for us peons. The serpent coil went out of his sentences. He was in danger of becoming a cult writer without a cult.

He eventually crawled from the wreckage, abandoning the pile of bodies on the front lawn for a solid marriage to Laurie Buffet, sister of the singer Jimmy Buffet. He also stopped drinking. His novels showed newfound maturity without muzzling his moon-dog wit. After the burnout absurdism of Panama, which read like Robert Stone and Barry Hannah exchanging personalities after a toke, he redeemed himself with Something to Be Desired, the collection To Skin a Cat,' and—especially—his critically hurrahed 1989 novel, Keep the Change (later turned into a TV movie by William Petersen, whose picky walk suggested he hadn't had time to break in his boots). Keep the Change had flow, which perhaps isn't surprising, since McGuane writes in an office whose porch overlooks the Boulder River. "By the door is a fishing rod he keeps just in case the trout start to jump," reports Time. Like Keep the Change, McGuane's new novel, Nothing but Blue Skies (Houghton Mifflin/ Seymour Lawrence), is set in Deadrock, Montana, where everyone's about halfway out the door. But there's more biting down at the lodge than tomorrow's blueplate special. Adultery in Deadrock has everyone doing backflips. Bedrooms are as busy as French farce. Coordinating backdoor intrigues and outdoor activities, McGuane has pioneered a whole new genre: the fucking-and-fishing novel.

Frantic action fails to stop McGuane's heroes from feeling they've fallen short somehow. From the outset his fiction has concerned frittering away one's legacy through drink, drugs, and bad choices of cellmates. His heroes are hippie souls who shun the stony paths of their puritanical fathers to subject themselves and everyone around them to elaborate head trips. (In this novel the son is stripped of his rightful due after letting a building he was managing be used for a pigsty orgy.) Nearly always there's a woman they're trying to win back, a symbol of steadfast love in a washing-machine tumble of casual sex. Eventually the hero recognizes the sheer emptiness of his catting around and decides to put down fresh roots for the hazy future.

Nothing but Blue Skies takes a spin around this familiar block. Spin is the word. Like all of McGuane's Montana novels, it clocks a lot of drive time, the cars his characters pilot telling us more about their personalities than their living rooms do. (Their front seats are their living rooms.) Frank and Gracie Copenhaver, the couple in Nothing but Blue Skies, have a two-car marriage. She drives a tidy Plymouth Valiant, while he steers a Darth Vader-ish Electra, whose "wanton deep pleats of its velvety upholstery invited stains." Their cars are about to take a fork in the road. As the novel opens, Frank finds himself left like a fool by Gracie, whose new lover he pictures as a drooling new face on Mount Rushmore. Oh, what might have been. "She had promised she would learn how to fish so that they would have more time together, but that plan went sour."

Without the love of a good woman, what's a man to do? In a McGuane novel, wander around in circles until he bumps into a kindred fool. Male bonding receives a tryout as Frank and his friend Phil go fishing: "Time to rip some lips," says Phil as trout leap through invisible hoops. Like the evolved men they aim to be, they "share" on the ride home, as Phil tells Frank that he caught his own wife playing bucking bronco with the family doctor. "I guess that if we didn't have trout fishing, there'd be nothing you could really call pure in our lives," Phil laments.

But fishing is only half of an f-and-f novel. With the tackle box stowed away, Frank has some impure prowling of his own to do. Bachelorette number one is a travel agent named Lucy, who takes him in hand: " 'Ooh,' she said, 'it's harder than Chinese arithmetic.' " But after Lucy has the poor form to act unladylike in bed ("All grace went out of her"), she vexes him further by not evaporating once they've had sex. "He went downstairs to the kitchen and put three shredded wheat biscuits into a bowl. To his aggrieved eye, they looked like sanitary napkins." Say what? Then he beds down with a radiologist named Elise, who also gets a good grip. "In Frank's room, she peered examiningly at his cock. 'The baleful instrument of procreation. Ooh,' she said, squeezing hard... " After her oohing, she has the poor taste to break wind in the bathroom. Once Frank has the room to himself, however, he feels a surge of pride seeing the twisted sheets. As he shaves he tells himself he doesn't need to tone his physique. "What difference does it make if my flesh is firm, he thought smugly, if they're going to put out like that anyway?"

McGuane's scenery is a beer-can-dotted paradise, his dialogue offbeat, his delivery sneaky-fast—but there's no substitute for plain story.

Unlike Richard Ford, McGuane doesn't bury his attraction/aversion to women under layers of mattress foam. It's right there on the ripsnorting surface, not only in mental leaps like the sanitary-napkins comparison but also in throwaway remarks, as when Frank's brother, Mike, says at the end of a discussion about putting the old homestead up for sale, "People who are out there trying to scoop up old family places are in on this bullshit. It's kind of like date rape. You can't get fucked if you don't spread your legs." For a woman to spring open for a man is to incur rancor for being messy, slutty, entrapping. Intercourse in Blue Skies is mostly slapstick, from the awkward screw Frank and Lucy later have in the back of a Buick (her butt hanging out) to a bit of coitus interruptus near the end. The slapstick is not only there for comic relief but to provide Frank with a safety release. The pratfalls allow him to . roll free, like Charlie Chaplin popping out of the machinery.

What McGuane never acknowledges is that for all their mooning what his men truly want from women is distance. Miles of it. The primary mode in Blue Skies is not mating but masturbation. In the novel's most revealing scene, Frank throws himself a pity party in his bathrobe. He has a fever and nobody loves him. "People magazine was always talking about the glitterati. Well, he belonged to the bitterati. This thought caused him to burst out in a laugh, but snot flew from his nose onto the bedcovers. He wasn't about to be overpowered by snot, and so, covering first one nostril, then the other, he recklessly blew snot all over everything..." The reference to bedcovers is the tip-off that we're not talking about snot here but semen, and that Frank's desire is to spatter everything around him with lone defiance. Duck, coppers! As if to underscore the message, McGuane then has Frank fall into a blissful state of sleep as he quotes the lyrics of the song that gives the novel its title. Blue skies smiling at me, / Nothing but blue skies do / see.. .No matter how deep McGuane delves into the everyday buzz (like Updike's Rabbit books, Blue Skies is crammed with news bulletins), his protagonists are drawn into solitary daydreams—cloudless swoons.

Daydreams are central to fiction, soap bubbles piped through our unconscious. The problem with McGuane's fiction is that he's never found a way to clear narrative space for his characters' unsuppressed wants. His books suffer from clutter, side trips, stop-start plotting, farfetched schemes (like Frank's plan to convert a landmark hotel into a chicken coop), facile nihilism ("He contemplated with a faint, annunciatory smile the idea that nothing really was important" —annunciatory, my...). Even Keep the Change, which has a smooth comic glide for most of its pages, contains colorful filler and peasant-appetite closeups of minor characters: "Ivan was a hearty, life-loving man, and it wasn't long before he was greedily passing hunks of steak into his mouth." McGuane's scenery is a beer-can-dotted paradise, his dialogue offbeat, his delivery sneaky-fast—but there's no substitute for plain story. Not that McGuane's admirers mind. The slack plotting in his novels leads friendly reviewers to praise them as "picaresque." Picaresque, schmicaresque—get to the point. Or at least crack some cold sweats from that pointlessness. No matter how far his heroes skid, their predicaments remain playground-cute. McGuane's always funning.

No one could accuse Walter Kim's first novel, She Needed Me (Pocket Books), of lacking crisis atmosphere. The author of an acclaimed collection called My Hard Bargain, Kim is a former deskmate at Vanity Fair. Always helpful, I tried my best to be a big brother to him during his brief incarceration. We went Christmas caroling together and played catch in the hall. But he had this faraway look in his eye. Saying adios to the shallow New York magazine scene, he headed to Montana to become a Real Writer. Since settling in Tom McGuane country, he's made a bobcat reputation for himself. His car flipped over in a daredevil traffic accident. His former agent and current agent engaged in fisticuffs at the A.B.A. convention. So it comes as no surprise that his first novel (whose list of acknowledgments includes McGuane's longtime pal Jim Harrison) eschews the tentative peach fuzz of his short stories. Confrontation is constructed into the opening sentence: "We met outside an abortion clinic."

The "we" is pro-life activist Weaver Walquist (what kind of name is that anyway?) and the woman he's trying to dissuade from abortion, Kim Lindgren. The novel is told in Weaver's voice, and Kim has a tough time securing the creepy-sincere tone. "The sacredness of human life, the destruction of American society, and why Kim should take a couple of weeks to consider options besides abortion. Those were the topics I hoped to bring up as we sat in my car an hour or two later, eating our burgers and french fries and trying to bring an awful day to a peaceful ending." Yet such is the strength of simple story that once Kim executes her decision, a sick hollow seems to hang in the air. Prochoice, pro-life—useless labels that fail to convey the almost animal sense of loss. She Needed Me would have packed more punch as a novella. But nobody buys novellas nowadays, news that has reached even the remote cabins of Montana.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now