Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowANN HUMPHRY'S FINAL EXIT

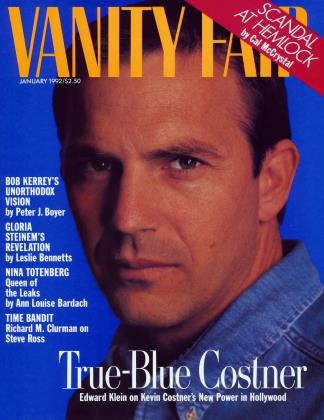

Will Ann Humphry's suicide derail the right-to-die crusade of the Hemlock Society, which she co-founded with her then husband, Derek Humphry, the author and "self-deliverance" guru? CAL McCRYSTAL reports on the last days of the woman whose death echoed haunting patterns set by Humphry's first wife and by her own parents, and followed the bitter breakup of her marriage

At 12:30 P.M. on Wednesday, October 2, Ann Humphry made a last, long-distance call from Windfall Farm, twentyfive miles northwest of Eugene, Oregon. In Los Angeles, Julie Horvath, a friend of Ann's, picked up the phone. "Julie? Can you talk? It's very important."

Horvath, who runs a training course for helicopter pilots, shooed her

student from the room. "Yeah, go ahead," she said.

"Julie," Ann Humphry said, "this is it. I'm checking out."

Horvath knew what those words meant: her friend was going to kill herself, surrender to two years of physical and mental anguish—mitigated by periods of extraordinary happiness—which began when her husband, Derek Humphry, walked out on her. Derek, executive director of the National Hemlock Society, was fast becoming known as America's "guru to the dying." Now Ann herself was preparing to carry out the organization's credo of "death with dignity."

Horvath, who had been with Ann at the farm only the day before, was stunned by her friend's words and struggled for her own. "What happened?" she managed to ask. Just that morning, Ann said, her attorneys had withdrawn from a $6.5 million lawsuit she had brought against Derek and Hemlock alleging that they had defamed her. "I just can't go on," Ann told her in a voice Horvath remembered later as quite calm.

Horvath tried to dissuade her, but Ann was firm. The conversation stopped and started, and both began to cry. "Where exactly are you going? When...?" Horvath asked.

"I can't tell you that."

"Ann, I love you very much."

"I know. I love you too. Promise me you will fly up and see my son and you will tell him. And promise me you'll tell Rick also." Then they said good-bye.

Ann Humphry saddled one of her three horses and led him into the trailer hitched to her pickup. She drove a hundred miles east, to the Three Sisters Wilderness Area, and parked the truck in a stand of trees. Mounting the gelding, she rode up a trail for several miles, then turned into dense forest. She unharnessed the horse, leaving him to wander free (he was later found by a riding party), and carried her tack to a tree, where she sat down and, leaning against her English saddle, opened up her bottles of pills.

Ann was still under the tree, lying in a fetal position, when the county sheriff's men found her six days later.

On the surface at least, it was hard to understand why fortynine-year-old Ann Humphry would take her own life. She had only recently defied death, surviving a bout with breast cancer, and friends noticed that she had begun to revive as well from the emotional wreckage of her divorce from Derek. Even stranger, however, was the eerie pattern her suicide seemed to trace, for Ann was the second of Derek Humphry's wives to meet a pre-arranged death. Sixteen years ago Humphry helped his first wife, Jean, to commit suicide as she lay dying of breast cancer. The book he wrote about the experience, Jean's Way, quickly became a mainstay of the nascent right-to-die movement. Celebrity followed with other books, lectures, the Hemlock Society—and money poured in.

Once an undistinguished, even dour London reporter, Humphry was transformed overnight into a font of radical enlightenment. He had hit upon a profoundly sensitive issue, and his beliefs were taken up by his followers and projected, as if onto a giant screen, for all the world to see. Those who had known him in his former life, myself included, now saw a changed man. With astonishing rapidity Humphry came to regard his actions as having a hugely magnified significance; like many a revolutionary before him, his ethos and his ego seemed to fuse.

On the very day Ann left Windfall Farm for good, Humphry was being taped by a British television crew, signing copies of his new best-seller, Final Exit, in a bookstore promotion, and prophesying that legalized euthanasia would be a "tremendous influence across the world." Dressed in a gray suit, striped shirt, and blue tie, Humphry was surrounded by copies of what he calls his "workshop manual," some opened to chapter headings: "Bizarre Ways to Die"; "Self-Deliverance via the Plastic Bag"; "How Do You Get the Magic Pills?"

Reviewing the TV report later, I am struck by his aspect—he could easily be a tonsured English priest. Deep Somerset tones solemnize his diction as he speaks of "a step-by-step method on how to die." The face is humorless. I detect around the mouth a certain tension; in the eyes, a certain wariness. He is not at all as I remember him. I am reminded of something Ann Humphry once said: "He gets tremendous validation [from his public]. There are all these Derek Humphry groupies everywhere. He loves traveling because he can talk and talk and talk about Jean and Jean's dying, and he becomes a hero. . . . He has referred to himself as a cult hero and to Jean's Way as a cult classic."

On learning that Ann's attorneys had resigned from her suit against him, Derek had turned to his newest bride and said, "This is not good news for Ann." When he learned of Ann's death, he added, "But I didn't imagine it would go this far." Indeed, they hadn't spoken for some time, according to observers. But in Eugene, it was well known that Ann had believed Derek wished her dead so that he could be rid of her forever, and that he had vehemently denied it. A half-page ad he placed in The New York Times several weeks after her suicide, describing her as "dogged by emotional problems," seemed an attempt to clarify the circumstances of her death and to erase any lingering suspicions about his moral culpability. The eulogy, signed by Humphry, was effusive yet somehow equally dispassionate: "A woman of Nordic beauty, enormous talent, huge generosity, a gourmet cook, and often wonderful company, at other times her depressions were so serious that she had to be hospitalized.' ' The ad also took pains to point out that Hemlock does not endorse "suicide for reasons of depression."

I had visited them both, already estranged, in Eugene in early 1990, seeking to understand the violent rift that had occurred between two people so dedicated to the controversial goals of the Hemlock Society and, it had long appeared, to each other. Ann was extremely distraught at her husband's departure, and the manner of it—he had left his good-bye on their answering machine—and she had checked herself into the psychiatric ward of an Oregon hospital for several weeks before my arrival. But she also filed her suit against Derek, charging him with intentional infliction of emotional distress and defamation of character, for describing her as mentally ill. For his part, Derek made it clear he wanted Ann removed from the Hemlock board, and instructed that the locks be changed to keep her out of the offices. Once she was off the board, he had Hemlock's attorneys draw up a "confidentiality agreement," which would forbid Ann to speak about the organization's affairs. She refused to sign it.

If Ann could not let go, Derek, it seems, was already somewhere over the horizon. He later told the London Daily Telegraph, "I left her because she was emotionally unstable, not because she had had a brush with cancer." She had soured him on the relationship; the passion had waned and so he felt no compunction about leaving. When I spoke to him, he didn't sound worried about the pain it would cause Ann to learn that he was already involved with another woman—one whose family owned a farm near Ann's. He had had a mistress in another city for five years before that, he explained, adding, "That shows the pitiful state of the marriage."

As Ann was putting her final plans into motion, Derek was busier than ever at Hemlock, spearheading a campaign to legalize euthanasia in Washington State. (The measure failed a month later.) He was also getting settled into his new life, having married the farmer's daughter, thirty-eight-year-old Gretchen Crocker, in May 1990. The couple had moved to a timber-walled two-bedroom house in the hills outside Eugene. Final Exit was being trumpeted as a likely Hollywood property, and there were 250,000 new copies of Jean's Way in print, targeted at the mass market. (Humphry's New York literary agent, Robert Ducas, recently told Variety that he had turned down two serious television inquiries about Jean's Way because he wants a feature.)

The law in most places currently prohibits euthanasia, but the First Amendment protects the publication of how-to manuals such as Final Exit and the

Hemlock Society's numerous case studies of "auto-euthanasia"—or mercy-killing oneself. One Hemlock publication claims that about 80 percent of Americans support passive euthanasia (pulling the plug) and that about 60 percent support auto-euthanasia. "The credo of Hemlock is that auto-euthanasia should be non-violent, painless and bloodless. It ought also to be aesthetic enough to be carried out in the presence of loved ones and to give them a chance to say goodbye." (The leaflet warns against certain methods—cyanide, for instance, which "has been likened to your blood boiling.")

Needless to say, Hemlock is perpetually losing members, but, Humphry explained to me, "we advertise. . . . Our girls take a steady stream of calls" on the group's toll-free number. Tragically, AIDS has been a boon, bringing many more young people into the movement, "[AIDS] changed the face of our organization," said Humphry. "Up to 1984-85 we were an organization of elderly, gray-haired ladies.

"We don't ask people what they're dying of—that would appear to be snooping," he added. Asked if he ever got fed up with the campaign, he answered emphatically: "No. ... I

won't stop until I've made change. ... I will go on writing about it, shouting about it. Put it this way: I won't shut up until the law is changed."

first met Humphry in the 1970s, when he was a reporter on The Sunday Times of London, writing about race relations. He was balding, lugubrious, industrious, and deadly dull—despite a high-pitched giggle. He was older and more waxen than most of his colleagues, "the epitome of suburban respectability," one reporter recalls. Another summons up the image of a man "who didn't sparkle or womanize." Then came the astonishment as he achieved sudden notoriety with Jeans Way, in which he described bringing, by prior agreement, the mother of their three children a mug of lethally spiked coffee on her breakfast tray one sunny day in 1975.

"The harassment [of Ann],the lack of compassion, the lack of deceny:the man was vicious."

A few months later, after answering a personals ad in a paper, Humphry met a young woman from Boston named Ann Wickett, a student at the Shakespeare Institute in Birmingham. ''It was strong love at first sight," he told me. ''I remember you were the first one in the office to see us together."

In fact, it had struck me as a touch insensitive that the widower was able to apply himself almost immediately to the zealous pursuit of female company.

But he told me that Jean had given him permission to remarry. ''Don't forget," he said, "I'd known for a good year that Jean was dying. . . . You've done a lot of thinking about what's going to happen [afterward]."

He and Ann were married the next year, and wrote Jean's Way together during a protracted honeymoon. They moved to America, to a house in Los Angeles. Humphry was exuberant: ''The golden immigrant! What more could you expect? Ann gave me the legal status: a new wife, a new life!"

He was unconcerned about the threat of prosecution for Jean's death. ''I could have got up to fourteen years in prison," he said, ''but I was very careful in preparing Jean's Way. I spent a lot of time in the library, with law books," and once finished writing he destroyed all his notes. Some felt, however, that Humphry could still be charged with ''making a buck out of his wife's death," in the words of one acquaintance. Indeed, for the first time his colleagues got a glimpse of a trait Humphry would later exhibit full-blown: an earnest, unapologetic self-centeredness. One saw it in the pages of Jean's Way, where the author's maudlin description of his own torment and his escape from it seems

to all but eclipse the predicament of his wife.

Ducas, Humphry's agent, reportedly said, ''It's the most tasteless thing I've ever read in my life. But it will make a fortune." He was right. Derek and Ann Humphry had effectively launched an industry of death dealing; he made his rounds of interviews and television talk shows, and in 1980 they concentrated their efforts under the umbrella of the tax-exempt Hemlock Society. Ann chose the name.

Hemlock seems to have survived the death of the woman who christened it. Many observers say Derek was clearly always the driving force, and he is a skilled chief executive: membership has risen steadily, and is up by more than 10,000, to 45,000, since the couple's divorce.

He has also been largely successful at damage control. Jean Gillett, Hemlock's treasurer, says Humphry made a visit to her home in Eugene shortly after he left his wife. ''He came over and just broke down completely, saying, 'Here, I've gotten all you people into all these problems,' " Gillett recalls, adding that she always found Ann's personality ''disagreeable," while Derek ''tried to be smooth, and always of an even disposition."

Henry Brod, a local Hemlock official whom Humphry fired over a policy disagreement, does not share Gillett's opinion. ''The harassment [of Ann], the lack of compassion, the lack of decency: the man was vicious. None of us liked what was going on, but we didn't let that interfere" with the group's work. According to Brod, ''Whatever Derek says is fine" with the Hemlock board. ''He's not on the board, he's executive director, but whatever he says they do. And he attends all meetings and dictates everything that goes on." Brod claims Derek met with each board member before the January 1990 meeting, at which Ann was voted out. ''[He] told them, 'Ann's crazy— she's mentally deranged, poor thing.' They always trusted Derek."

The residents of Monroe, the community nearest Windfall Farm, are more suspicious. "If Derek had come [to Monroe] after Ann's death, he'd have gone out in a box," says Pam Wilson, who runs the local feedstore. "The people blamed him because of the things he was saying to the media, that Ann was mentally ill, that she was unstable."

"Ann did not commit suicide out of impulse," insists Julie Horvath. "It was a long, two-year battle. She was stripped of everything—her dignity." Horvath, who was Ann's riding instructor when they first met, joined Hemlock, then dropped her membership when Ann was ousted. "I just hope and pray that people will see what Derek is about, that they'll wake up and see what Hemlock stands for," she says. "Hemlock failed miserably. If they couldn't be there for a cofounder, they're not going to be there for the little guy. "

Rita Marker, who runs an Ohio-based group called the International Anti-Euthanasia Task Force, had frequently debated the subject of "mercy killing" with Derek before the marriage ruptured. "We started the task force in 1987 because there was no visible opposition to euthanasia." Over the years, she says, "Ann indicated to me, and to others, that she had changed her viewpoint entirely as to the legalization of euthanasia. It was something she had not been aware of be: fore being diagnosed as having cancer. She realized what pressure there already was on people to die and get out of the way; to legalize euthanasia would only add to that pressure."

"There was so much death. Derek was working like a fiend on it all the time."

Rita Marker calls Derek Humphry "a monster," because "he used his first wife's death and now his second wife's death to further his agenda."

Some suspect the key to Derek's behavior may lie submerged in his own unhappy past. He is described by several women who came into contact with him as a person who openly sought sympathy and comfort during his troubles with Ann, yet Derek's hallmark has always been his ability to move on, seemingly impervious to the ravages of catastrophe and loss. He is a survivor, but not a healer, and he has learned to elevate that condition into an all-consuming vocation.

It was only after becoming truly famous as the boss of Hemlock and guru to the dying that Humphry seemed relaxed enough for confidences. I then learned that the man who left Ann Humphry was once abandoned himself. He was about four years old and the woman who bolted was his mother.

He was born on April 29, 1930, to an Irish model from Cork who had two sons—first Garth and then Derek— with a traveling salesman in Bath, Somerset. "Life fell apart almost immediately for me," Humphry said. "I think [they] were both tearaways— they loved life.

"My father got custody of the two boys, and she was much upset, so I gather, and took off for Australia," he continued. A few years after the divorce his father spent a year in jail for fraud, and the two brothers were shifted around among relatives in Bristol. They were told he had gone away on "a business trip."

His mother married an Australian and resurfaced only a few times after that, when her sons were young adults. Then she left their lives forever.

he last two years were a lot of trouble, but I really thought Ann had gained a good deal of ground," says her cousin Nancy Raymo, puzzling through the reasons for Ann's suicide. "She had a gentleness and a caring that made her very vulnerable." Although chemotherapy had left her exhausted, frequent checkups for breast cancer revealed that she was, at least for the moment, in the clear. Ann lost confidence, however, in late 1990, when she underwent surgical reconstruction of her left breast, was unhappy with the results, and went back for a second operation. Raymo, who \talked to her at the time, says, "I have never heard such despair in my entire life. She was sobbing and said, 'I have been completely butchered.' And then she had to go through recovery alone. And the legal fights [with Derek] were still going on, and she had this fear of running out of money and not being able to support herself. "

Yet again Ann Humphry recovered and sought to renew her grip on life. Last January, two things happened which were to give her strength. A new man entered her life, Rick Urbanski, a physician at Eugene's Sacred Heart General Hospital. Soft-spoken and intense, Urbanski was a self-described city boy who was enchanted with Ann's knowledge of farming and animals. She invited him to Windfall Farm, and, he says, they began a relationship. "Ann and I were lovers."

The second happy event was the rediscovery of Ann Humphry's biological son, Robert William Stone, a twentythree-year-old fine-arts student at Montreal's Concordia University, who grew up in Toronto with his adoptive parents. Two years ago, Bill told them he wished to meet his birth parents; an adoption-disclosure agency helped him find Ann, and she told him the story of her life, and of his beginnings.

She was the younger of two daughters bom in Boston to Arthur and Elizabeth Kooman. The family was fairly wealthy (Arthur was a banker), conformist, and respected. She was sent to a boarding school run by nuns in Tennessee, then went on to Boston University. By the time she embarked on a master's degree in Toronto, Ann Kooman was a sheltered, introspective young woman, a voracious reader with little knowledge of the real world. When she fell for another student—named Arthur, like her father—she fell hard. And when she got pregnant and he didn't want to marry, she broke into pieces.

The pieces were picked up by Tom Wickett, a lawyer who helped her put the child up for adoption. Nancy Raymo describes their subsequent marriage as apparently one of "convenience"; it lasted only a year, as the young mother continued to grieve over her lost son and sought in vain the comfort of her censorious parents. Toward the end of her life, Ann Humphry talked to friends about those years. During her marriage to Tom Wickett, she "attempted suicide and was institutionalized for several months because of that," says Rita Marker. "Ann did not in any way attempt to keep that a secret."

Her pregnancy "was a family shame," says Ann's cousin. "[Her parents] didn't want their friends to know. They were very angry with her. Even though she'd been assured her baby had gone to a good home, she always worried about her decision." When the adoption-disclosure agency contacted her last January, she could hardly contain her joy and relief. "When she got his first letter, she cried and cried and cried," says Julie Horvath. "Bill's arrival [at Windfall Farm] was the one thing she'd been hanging in for."

When Bill came to Windfall Farm last summer, says Raymo, "within twenty-four hours they were finishing one another's sentences. Bill just felt like he'd found his soul mate. They had a wonderful ten days."

Ann and Bill went camping in the Three Sisters Wilderness Area. "She was so happy," says Bill. "We spent a lot of time just talking and talking. We caught up with each other's lives."

Ann told her son about the book she was trying to write, despite its rejection by at least one literary agent. She planned to title it Hemlock Unraveled, and described it as a philosophical narrative on where she believed Hemlock had strayed from the path embarked upon in 1980. Ann Humphry still believed in the principle of "self-deliverance," but now she felt that it would almost certainly encounter difficulties in practice: the sheer momentum of the Hemlock machine might trundle over fragile personal emotions, she said; the powerful group psychology of the organization could strip the individual of his ability to choose. "The book was semi-autobiographical," Bill says. "It wasn't about Derek. . . . The fact was she'd been victimized, and hated the idea of me regarding her as a victim. . . . She said that when she survived this she wanted to tell her own story. . . . Instead of spending all this time on death, [she wanted to spend] time on just getting the farm going. I mean, there was so much death. Derek was working like a fiend on it all the time, but she was pulling away. She was getting tired of death."

If Derek Humphry claimed his wife could be "a perfect bitch," he wasn't the only person who found Ann Humphry contentious and difficult to deal with. Her attorneys withdrew from the suit she was bringing against her ex-husband because they found her repeated interference with their handling of the case intolerable. It appears that this event severed her will to live. Yet Ann was stalked by other demons—Rick Urbanski says Humphry's abandonment "hurt her very, very deeply." She also worried about a recurrence of cancer. And her closest friends say that Ann never got over her remorse about her parents and the manner of their death in 1986.

It was four years after Humphry had published Let Me Die Before I Wake, case studies of self-deliverance, from which, as he later put it, "thousands of dollars poured in." His parents-in-law, the Koomans, were ailing, and had joined the Hemlock Society. Arthur, ninety-two, suffered from congestive heart failure; Elizabeth, eighty, had never fully recovered from a stroke. They told their daughter they wished to die with dignity.

Continued on page 141

Continued from page 86

Derek and Ann Humphry flew to Boston to help them. Later, in her book Double Exit, "fictionalized" to avoid criminal charges by the Massachusetts authorities, Ann described in painful detail how she and Derek took the phone off the hook, double-locked all the doors, and fed a gruel of applesauce, ice cream, 7UP, and Vesparax to the elderly couple.

Ann's last words to her mother were: "Remember when I was a little girl and sick and hated my medicine, and you made me take it in a hurry?" Derek told me, "She helped her mother to die and I helped her father to die. ... I was very fond of her father, and got on with him awfully well, so I sat with him and he was holding my hand as he died. He said, 'Good-bye, Derek,' and I said, 'Goodbye, Arthur.' "

With her $300,000 inheritance, Ann purchased the farm in Monroe, naming it, without ironic intent, Windfall. But it brought her little peace of mind. "I don't know if that's something anyone can get over," Urbanski says. Nancy Raymo agrees: "I think it just ate her up. We had a fairly religious upbringing, and it is one thing to be writing about death, and another when it comes so close to home. For Derek it was his usual, but for Ann it was not. Derek was not able to connect with the fact that she was having an emotional struggle. Some men can be an emotional support, but this one couldn't."

Indeed, a fateful crack appeared in their partnership as Ann began to question the integrity of what they had done. All her life her relationship with her parents had been strained, and now she had, however gently, disposed of them. She became a prisoner of that furtive act, doomed to replay it over and over again in her head. But while Ann was trapped in guilt and self-doubt over the Koomans' deaths, their orchestrated demise appeared only to build Derek's confidence in his mission. Perhaps it comforted him to think that his parents-in-law had followed the same course as Jean; perhaps their decision served as a kind of absolution of his own actions. One thing is certain: he was impatient with his wife's protracted grief. The warning signs were there. He could move on; she could not. Humphry later told me he had "tried to make it up to her'' at one point with sex. "I did make love to her, but she wouldn't make love to me. It was just like masturbating in her vagina. She's not a good sexual lover. ''

Humphry's irritation at his wife was possibly exacerbated by the blows that struck his own family at around the same time. One of his three sons was jailed in England on a drug charge. Then his brother, Garth, a car dealer near Bristol, suffered irreparable brain damage during a minor operation as the result of a medical accident. Humphry flew to England for a family consultation about Garth's vegetative state, and instructed the doctors to turn off the life-support machine. "I think Derek doesn't cope with dying on a personal level,'' Ann told me. "He just went to pieces when his brother died and was very, very resentful of mortality. And when my parents died he just didn't want to know—he was terribly angry, angry at me, probably because he thought I wasn't there for him. ... He did say, after my parents had been dead for seven weeks, T never want to hear any mention of your parents again. . . . I'm sick and tired of hearing about them.' '' Ann added that she had asked Derek, " 'Why is it that my parents, who died the way they did . . .you forbid me to speak of them ever again? When Jean died, I spent two years nursing you through your grieving, wrote a book with you about Jean, and Jean's been a part of our lives for eleven years.'... He said, 'Well, we made a business out of Jean's dying. That's different.'

It was to be Derek, however, who brought up the Koomans' deaths again. In response to Ann's public outrage about his lack of compassion after he left her, and his handling of Hemlock's financial affairs, he put another message on the answering machine: "If you continue this stupid fighting one step more, I shall give your sister and nieces a full statement that you've committed a crime in helping your parents to die. They will then be able to sue you for the $300,000 you inherited. You must know that in law you cannot benefit from the result of a crime. Just live quietly, regain your health, agree to a divorce where we keep our own property, and let's get on with our lives. Otherwise I fly to Boston. I'm in deadly earnest. Think it over. Bye.''

It was a message not calculated to alleviate his wife's grief, a message of which Humphry later told me he was "ashamed.'' But it achieved its immediate purpose, persuading Ann to cease her invective. Or at least to bide her time, for on the morning of her death she put into play an astonishing counterattack. In addition to tidying her house and feeding her animals, she sat down at her typewriter and composed a note—since highly publicized—to Derek Humphry. The note said:

Derek:

There. You got what you wanted. Ever since I was diagnosed as having cancer, you have done everything conceivable to precipitate my death.

I was not alone in recognizing what you were doing. What you did—desertion and abandonment and subsequent harassment of a dying woman—is so unspeakable there are no words to describe the horror of it.

Yet you know. And others know too. You will have to live with this until you die.

May you never, ever forget.

She signed the note "Ann'' with a ballpoint pen. An examination of the signature suggests that her hand trembled.

She made a copy of the note and under the typed text composed a short message to Rita Marker, the anti-euthanasia activist, who had become a close friend. It read, "Rita: My final words to Derek. He is a killer. I know. Jean actually died of suffocation. I could never say it until now; who would believe me? Do the best you can.''

In Jean's Way, Humphry refers to the fact that, after giving his first wife the lethal drink, he stood ready to place a pillow over her face in the event of a prolonged death. He records that he did not have to use the pillow. But Ann later claimed that Derek had covered Jean's face with it and smothered her.

There is no evidence to support Ann Humphry's version, and so its truthfulness cannot be tested—other than by putting it to Humphry himself. He declined to be interviewed by me for this article, but told a reporter from Inside Edition that the charge "is a totally false accusation made by a disturbed woman. It's not true. . .and it's the sad story of an unhappy and disturbed and angry woman making wild accusations.''

Although these "wild accusations'' from the grave are taunting, it is unlikely that they will do any lasting harm to Derek Humphry's image. It is difficult to dismiss his vigorous and repeated denials. And, further, one may question if—for a person already committed to the end result—there is any real difference between delivering a lethal dose of poison and stopping the flow of oxygen. Still, Ann's friends have mounted an anti-Humphry campaign, spurred on by the note to Rita Marker ("Do the best you can'') and by a videotape of a conversation between Ann and Julie Horvath made the day before her death. In it, Ann says Derek once admitted to her that "there was some sort of choking and regurgitation'' as Jean expired and that he had "suffocated'' her. "Derek had always said to me, 'Just use a plastic bag or a pillow.' '' She reveals for the first time that she held a plastic bag over her mother's mouth at the end. "But I walked away from that house thinking, We're both murderers.''

In the end Ann, who after the divorce slept with a .22 beside her bed for security, needed bodily protection only from herself. And Derek, once again, was left to explain to the world what had happened.

"It's extremely painful to have lost two wives," he recently told a reporter, with his customary stoicism. "It's like a Greek tragedy."

Whatever else remains unknown—and unknowable—that, at least, is the absolute truth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now