Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHockney's ABC

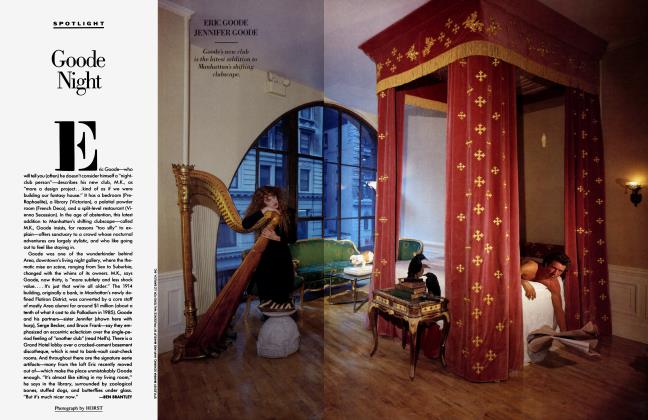

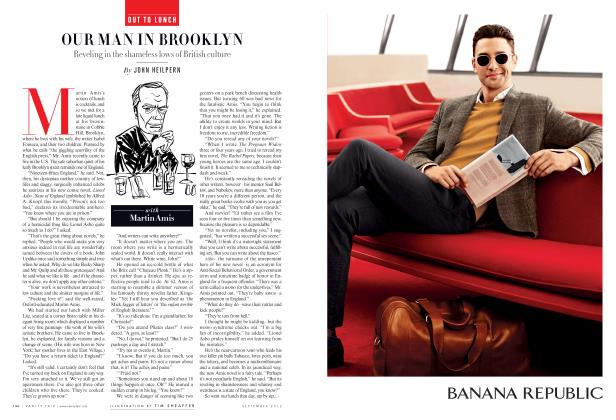

SPOTLIGHT

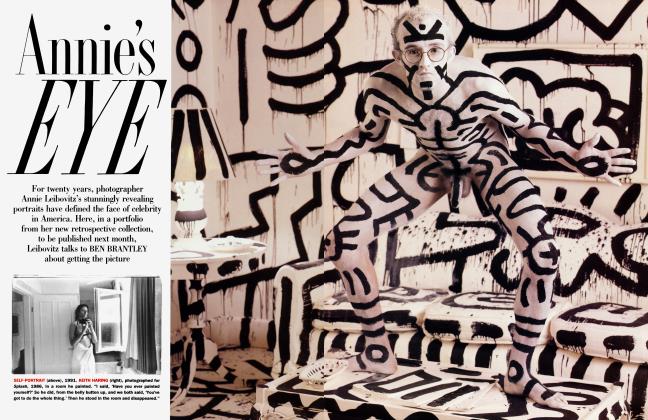

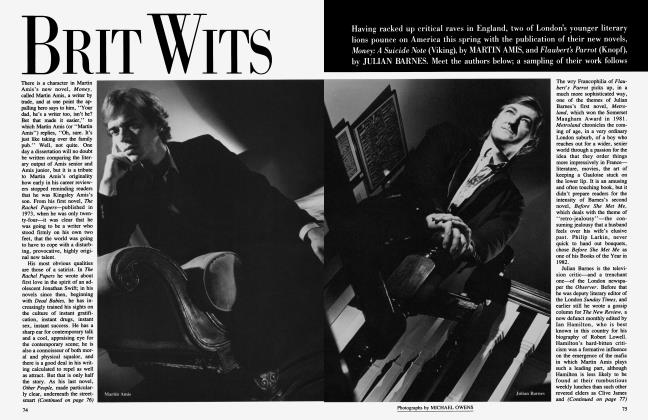

the versatile characters shown at right, H and U, are two of the twenty-six stars of Hockney's Alphabet, an abecedarian volume created expressly to raise money for AIDS programs in England and the United States. Drawn with brightly sophisticated ingenuousness by David Hockney, the letters are supported by written entries composed by a correspondingly wide-ranging host of novelists, poets, and playwrights, each of whom was assigned a letter by the book's editor, Stephen Spender. The results are an elegant, often surprising exercise in free association, which ranges—as the passages by Martin Amis and Julian Barnes demonstrate here—from the profoundly personal to the blithely semantic, from the ontological (Joyce Carol Oates on B, as in Birth; Paul Theroux on D, as in Death) to the practical (Doris Lessing, who provides lyrically recorded recipes for Pumpkins). Some of the pairings manifest a devilish appropriateness (Erica Jong got Norman Mailer, F). Only two of the entries directly address the issue of AIDS. But each, in its own way, shows how twenty-six primal characters—an incongruous group, after all, of mere lines and curves—can be carefully assembled into something that will always testify to the pains and pleasures experienced in the short passage of any life. They represent an effecting contribution to what Spender describes in his poem "The Alphabet Tree" as "a dance throughout Time.. .Where the living read / Those more living—the dead!" The book, to be published by Faber and Faber in England and by Random House in the States, will be launched next month. A deluxe edition was made possible by a donation from William A. McCarty-Cooper, the American interior designer who died of AIDS. Proceeds go to the AIDS Crisis Trust in England and the American Friends of AIDS Crisis Trust in the U.S.

BEN BRANTLEY

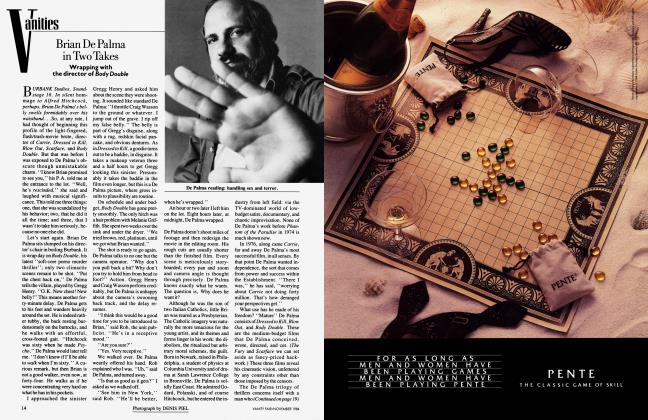

HIS FOR HOMOSEXUAL

When I was nine or ten, my brother and I obliged a slightly older boy—Billy—on a deserted beaeh in South Wales. It didn't last very long, and my brother and I took turns, but our wrists aehed all day. These few minutes—later totemized by a friend as "Martin's afternoon of shame w ith Billy Bignall"— represent my aetive homosexual career in its entirety. But the memory leads on to another memory: the nausea and despair 1 experienced when, at the age of thirteen. I saw my Best Friend walking from the games field with his arm over the shoulders of another boy.

I wish I understood homosexuality. I wish I could intuit more about it—the attraction to like, not to other. Is it nature or nurture, a predisposition, is it written in the I)NA? When I think about it in relation to myself, it is not the memory of Billy Bignall that predominates, but the other memory, somehow expanded. so that its isolation and disquiet become something lifelong. In my mind I call homosexuality not a "condition" (and certainly not a "preference"). I call it a destiny. Because all I know for certain about homosexuality is that it asks for courage. It demands courage.

MARTIN AMIS

We were trying to decide the most sinister word in the English language. We started, unsurprisingly, with horror-movie stuff: necromancer, holocaust, rabies, syringe, gout. Soon we realized that this was mere representational ism: bad thing, bad word. So we became adjectival: crepuscular, curdled. inspissated. fetid. Then we tried for suggestiveness: ought, ganglion, ukaz. We got skittish: gherkin, someone suggested, and VAT. twin set. virtue; what about sinister itself—isn't that pretty sinister? We got stuck and went back to bad things again: wen, oven, plague. Finally one of our number said. "Unless.. ." We all looked at her. "Yes?" "No. that's the answer," she replied. "Unless..." It's the oiled hinge of a sentence, a slick clunk of the points. Remember it from frightening stories in childhood: Unless this isn't the door we came in by. .. Imagine it in bankruptcy: Unless I've misread the figures. Fear it close to home: Unless, of course. I don't love you any more. It remains menacing even in cliches: Unless I'm very much mistaken. Whereas but is a short-arm jab in the face, unless is the subtle creak from underfoot w hich tells you that you're standing on a trap-door. Its often attendant trail of dots (whether written down or not) extends that moment anguishingly: Unless. . . Then the padded thump and your echoing wail as you fall through all you'd believed. known, relied upon. Unless: the most sinister word in the English language.

JULIAN BARNES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now