Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMANHATTAN'S PARTY MAGICIAN

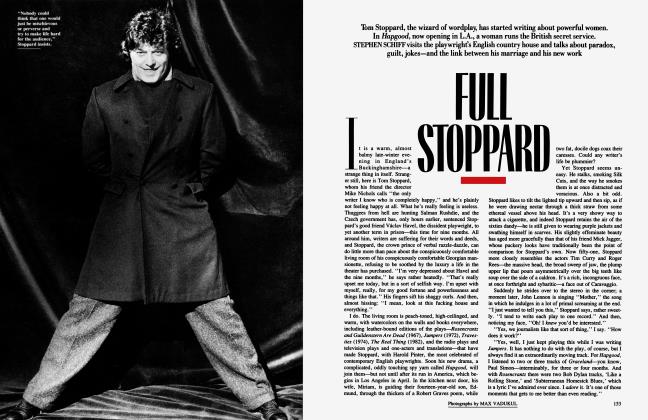

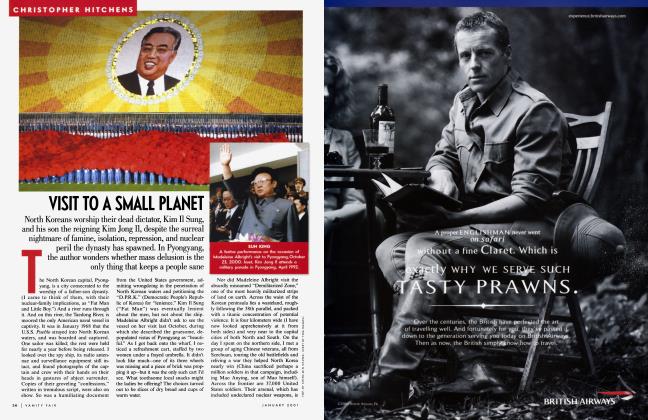

BEN BRANTLEY

Robert Isabell is the shy guy behind N.YC.'s most beautiful parties

Nightlife

The nineteenth-century fort —a two-hundred-foot circle of red sandstone with fortyfoot walls and an attractively decrepit patina—definitely had possibilities... It was an atypically warm afternoon in January, and Robert Isabell, the New York florist and party creator, had just ferried over to Governors Island, the Coast Guard base off the southern tip of Manhattan. Eyes narrowed into evaluative slits, he was giving the 1811 fortress, named Castle Williams, the keen aesthetic once-over he brings to everything which crosses his line of vision. Governors Island, settled by the Dutch in the early 1600s, had just figured in the news when Reagan, Bush, and Gorbachev summited there, but Isabell wasn't pondering history. He was assessing the view of the city skyline—"breathtaking, the closeness of it: it's just right on top of you"—and thinking that all you really needed was an improvised ceiling, and a dining tent...Then, if you shuttled the seven hundred or so people over.. .No doubt about it, Governors Island would be an absolutely swell place for a party.

And so, on April 11, Governors Island was to be colonized by Europeans again. Designer Giorgio Armani would be "celebrating his presence in America," as his press office would say, with a dinner and fashion show. And Robert Isabell would be transforming a Federal fortress into a temple to cool Milanese minimalism. It would be another manifestation of Isabell's particular ability to conjure up what hotelier Ian Schrager calls " instant environment. ' '

In recent years, Isabell has transformed a CBS soundstage into a verdant, wooded park (for a dinner honoring William Paley); the restaurant of the Metropolitan Museum into a Directoire folie d'or with gold-dipped magnolia leaves, tasseled chandeliers, and an eighty-foot-long trompe l'oeil garden wall (for the wedding of Jonathan Tisch and Laura Steinberg); the soaring atrium of the World Financial Center into a winter garden lit by four thousand candles (for a benefit honoring French designer Christian Lacroix); a slim corridor of the New York Public Library into a thirties ship deck (for the library's Ten Treasures Dinner); and the dilapidated basement of the Century Paramount Hotel into both a silver-walled re-creation of Andy Warhol's sixties Factoiy (for the Warhol memorial lunch) and a New Age fantasyland inspired by the film Legend (for Cher's Halloween party). He also orchestrated the Cape Cod nuptials of both Caroline Kennedy and Maria Shriver, and would like, he says, to move on to vaster projects: an Arabian Nights wedding in the Middle East, perhaps, or, his ultimate dream, an Olympics opening.

Along with a handful of intensely competitive rivals—especially Philip Baloun and Renny, his former employer—Robert Isabell rules New York's party circuit, a master of the ritualized revels which can trace their forebears to the princely masques of Leonardo da Vinci and Inigo Jones. In the Reagan era, when the relaxed disco bash was eclipsed by increasingly elaborate and costly fetes, ranging from charity balls to product-pushing galas, the party organizers flourished. The scale on which they worked mushroomed, and so did their prices, which can start at around $2,000 and escalate well into six figures. With the Bush inaugural signaling a more discreetly expensive style of entertaining, Isabell may have an edge on his designing peers. While he admits any employer would be reckless to give him carte blanche—"You don't know what that means," he says ominously, "you don't want to test me on that"— his visual trademark is restraint.

"Robert creates an atmosphere that isn't theatrical as much as it is elegant," says society princess Blaine Trump, who chaired the Lacroix gala. An appropriately fastidious man in a black Armani suit, Isabell, thirty-six, says his greatest asset is ''the simplicity I can bring to outlandish parties. It never goes over into the ridiculous or gaudy. It can stop." Schrager describes him as an artist whose medium is "great taste."

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 82)

Conducted from a cavernous warehouse in the West Village, Isabell's business, like that of his competitors, is rooted in flowers, arranged and sent for the people who can afford them (bouquets go from $100 to $ 1,000-plus). Beyond that, he sees himself as a weaver of illusions, a bringer of evanescent, candle-lit harmony to a world harshly illuminated by electric bulbs. He eschews the idea of designing sets; theater and film seem too static, too permanent, to him. What he loves is that "living thing, a party, where you really change the space for an evening. The fantasy, the magic, that's created just for an instant. And then it's gone."

Spend time with Robert Isabell and you'll see the world riddled with gross breaches of taste. Walking down a street, he flinches repeatedly: an aqua leather sofa in a shop display; an obese woman in tight tomato-colored slacks; a badly lit store window. He admits he can't walk into a room without instinctively wanting "to rearrange it, to change some colors." When, briefly, in the early eighties, he kept a flower shop at Bergdorf Goodman, he shocked the store management one Saturday by painting the columns of his alcove black. He hadn't consulted anyone and the space was immediately repainted. Isabell subsequently left the store, but has continued to work with it on special projects. "I've found over the years," says the store's president, Dawn Mello, "that if we disagree with him we're usually wrong." "He could arrange somebody's mind, probably," says his friend Elizabeth Saltzman, a Vogue fashion editor, whose wedding was done by Isabell.

This unshakable self-assurance has alienated a few strongheaded clients along the way. "He doesn't suffer cheats and bores and people who are tasteless," says George Trescher, the socially active planner of benefit galas. "It's wonderful to have that quality, but it also gets you into trouble." "He's not as diplomatic as he could be in certain situations, like dealing with unions," says another sometime associate. "He wants things done—that's the way he wants it and that's that." Ivana Trump is said to have had her run-ins with him, but Gayfryd Steinberg says she finds him amenable to suggestion, although she adds, "He's got to be on a budget."

Isabell's professional certainty is set off by a surreally calm and self-effacing manner. He is patently uneasy talking about himself, and so genuinely shy that when the barrage of publicity hit him in the wake of the Steinberg and Kennedy weddings he had to see a psychiatrist to learn how to deal with it. "He said he could barely hear me, the first time I went there," Isabell says. Before that, he wouldn't even let friends take his photograph, and he still tends to freeze when a tape recorder's running. With clients, he is polite, diffident, smiling, remote. In a traditionally flamboyant profession in a noisy city, his quiet is exotic. "He's like a monk," says novelist Judith Green, whose apartment Isabell decorates for Christmas. "You almost expect him to come in and kneel down and face Mecca." This, in a world where social doyennes expect flowery sycophancy from their florists, can be both an asset and a disadvantage. Says Steinberg, "I'm sure there are people who are more comfortable with a more aggressive kind of personality, who don't feel he could do a great party without being a party like person, which he just isn't."

Indeed. With his dark-haired, neatly sculpted good looks and intriguing inscrutability, Isabell could no doubt make the transition from the wings of a party to a place at the hostess's table. "I hate the idea of all those social butterflies touching him," says Armani vice president Gabriella Forte, who worked with him from his earliest years in New York, "but he's just so clean, and so out of it, it doesn't faze him." In fact, the possibility of a social career holds little interest for him. Trescher recalls Isabell's discomfiture when, after a party was well under way, some of Trescher's helpers joined in on the dance floor. "Get them off. They shouldn't be there," he was heard to hiss at this melting of the proprieties. "I don't play that game," Isabell himself says flatly. "That's not what I aspire to at all. I'm just interested in standing in the comer and watching everything."

Voyeur. The word echoes throughout descriptions of Robert Isabell, by himself, his friends, his employers. "Robert knows what a hot place is—a hot club or a restaurant or when a certain person has arrived," says Schrager, "but he's not really a part of it. And I think being a voyeur gives him an advantage, because he doesn't get immersed in the whole scene. He's like an observer, who sees what's going on and can be very succinct about it."

It's an almost Olympian detachment, this joy in meticulously setting a stage and then stepping back to watch the actors. I observed the process while watching Isabell prepare for the library's Ten Treasures Dinner. Assorted interior decorators and designers were creating theme rooms throughout the library. Isabell, sponsored by Bill Blass and Sharon King Hoge, wife of Daily News publisher James Hoge, was showcasing the library's map collection. They were creating an Anything Goes-type ship deck in a small corridor. "If we'd had a bigger room, it could've been.. .different," he had sighed the day before, "not that it's not great, what we're going to do." With his gleefully industrious ten-member staff—a uniformly well-scrubbed cadre of young men and women who had previously worked as everything from draftsmen to waiters—plus various lighting and carpentry technicians, he erected walls (with portholes through which you could see rare maps) and created a false ceiling out of net woven with streamers and balloons. He didn't just supervise: he repainted the doorframes himself, after deciding the initial color lacked contrast, and actually seemed most content when sweeping up the floors. Several times security officers stopped him because he wasn't wearing a clearance badge—"I hate those things"—and library staff remonstrated when they couldn't open their doors because of all the balloons. He met each new irritation by slightly squinching his impassive smile, then continued with monumental purposefulness.

As well as the ship deck, he was doing the floral arrangements in the dining area for decorator Suzie Frankfurt. There, he stripped off his jacket to build a table out of cinder blocks (which he rebuilt four times) for Frankfurt's ten-foot antique vase. He filled the vase with an improbable, perfectly proportioned arrangement of immense apple-blossom branches laced with white peonies. When the guests began to arrive, he was still adjusting the lighting and grumbling that there should have been more candles on the room's ledges. "Life was so much nicer before electricity,'' he murmured.

The giant vase was the hit of the evening. "Oh, Bobby, the sca-a-a-le," said Annette Reed. "Divine," said Bill Blass. "The most beautiful thing I've ever seen," said Lee Radziwill. Isabell mumbled inaudible thanks and detoured through a back corridor where Glorious Food was preparing the meal. He passed a table set for him and his team. "They set it every time," he said, "and we never use it. I would never eat there." When I remarked that it was a treat to see both sides of such an event, he said, "But that's what I love—it's all this and all that. It's like living on the comer of Park and Ninety-third Street." As we leaned over a stair railing and watched the crowd sweep into the dining room, he offered a few random criticisms. "Did you see that necklace? It really knocked me over. It's so ostentatious." But he also loved the whole mise en scene. "Aren't you glad you're in New York?" he asked.

The giant vase was the hit of the evening. "Oh, Bobby, the sca-a-a-le," said Annette Reed "Divine," said Bill Blass.

His enraptured insider/outsider view of Manhattan was shaped in wintry Duluth, Minnesota, where his father worked for the local power plant. He doesn't like talking about his early years, and thrusts his hands beneath his jacket when the subject comes up. "Where I grew up, you had nothing else to do but fantasize," he says. In that environment he was a rebel, he says, "in not settling for the expected." Adds a friend, "I suspect he had your basic miserable, lonely childhood." But Isabell says he appreciates the values of the region—"that whole Protestant thing of hard work, and the idea that you'd never say anything to hurt anyone." And he made enduring friendships—for the Kennedy and Shriver weddings, he flew in several former colleagues from the area to assist.

At the age of nine, after school and on weekends, he was apprenticed in a florist's shop—"It had the only nature you'd see for nine months, except for a skating rink"—and by the time he was eighteen had his own apartment. He moved to Minneapolis in the early seventies, and eventually ran a florist's there. But, he says, "I just always knew I'd live in New York. And there was never any urgency to get here." In 1979, on his first visit to N.Y.C., he joined the crowds outside Studio 54, and found himself suddenly being pulled inside by an arbiter at the door. It was Steve Rubell, Schrager's partner in the club. "Imagine that," Isabell says today, "never even having heard of Studio 54. I thought I was going to have a heart attack, I was so excited."

The following year he moved to Manhattan and worked for Renny. It was evidently a less than amiable association: both refuse to talk about it now. He left Renny a year later, with $200 in the bank to start his own business, taking along a number of key clients, including Bergdorf Goodman and Giorgio Armani. "He was like a runaway from Minnesota," says Forte. "For me, he was the only person at the time who didn't want to be French, or was some sort of queen who just made floral arrangements. He was a very simple, kind, attentive young man with an extremely good sense of architectural space and design."

He also recaptured the attention of Rubell and Schrager, and when they reopened Studio 54 in 1981, after time in jail for tax evasion, they enlisted Isabell for special projects. This working relationship, particularly with Schrager, has remained key. He calls Schrager "my best friend," and they have evolved remarkably similar designs for living. Both drive black Jaguars, and Schrager says he consults Isabell on all aesthetic questions, including the decor of his hotels. When Schrager's brother moved to Florida recently, Schrager flew Isabell down to fill the apartment with flowers and plants. And when Schrager and Rubell bought a house in Southampton last summer, Isabell was out there the first weekend, painting the main floor white, covering the existing furniture with white canvas, and filling the shelves with flowers and candles. When Schrager and his girlfriend arrived, they discovered that "within twenty-four hours he'd transformed the place." Isabell even bought all the kitchen equipment personally, at Zabar's. He was in a particularly

good mood that day—"I love spending other people's money"—and merrily filled a cart with all-copper cookware and a heart-shaped waffle iron. When I pointed out that copper wasn't always practical, he answered blithely, "It's not what it does, it's how it looks, right?"

There is no kitchen at all in Isabell's own home, a one-bedroom apartment on a scenic West Village street. He had the fixtures taken out because they cluttered things too much. He seems, in fact, to have created as deliberately blank a space as possible—a sort of screen, perhaps, on which to project the endless plans for other people's temporary worlds. The apartment's walls are painted a special shade of white called 1984 designed specially for him by a friend, colorist Donald Kaufman (who calls it "a cool, violet white like the mist of ice crystals"); its floors and its spare, minimal furniture are black. It is discreetly lit in varying washes of color from hidden fixtures, and Isabell says he never has flowers there. Very, very few people, he adds, have ever seen it.

Last Halloween I watched Isabell at work on the costume gala to launch Cher's fragrance, Uninhibited, in Rubell and Schrager's Century Paramount basement. It was a particularly elaborate job, involving a cast of fortune-tellers, performers, and tableaux vivants in special settings. Isabell had overseen the construction of a stage and assorted tents, hung in gilt and lame and satin, and had the place painted in a black sprinkled with "a special glitter ten times the price of real glitter." Once the party (waited by Glorious Food boys and girls with fairy wings attached to their tuxedos— Isabell's idea) got under way, all the guests in satumalian costume seemed faintly anachronistic, more like something from Isabell's 54 epoch. "There used to be a dozen different big parties on Halloween night," he said. "Now there's only this one. It's another time. There's a little less magic, a little less spontaneity."

We stayed on until two or so, well after the last guests had departed. When we left, the street was empty. The warm lights at the party's entrance had been snuffed, and the special press tent Isabell had erected in a parking lot across the street had already come down. The only reminder of the party was a trail of metallic dust shimmering in the streetlights. "Look," said Robert Isabell, with evident satisfaction, "the tent's gone. It's like it never happened, except for the glitter."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now