Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

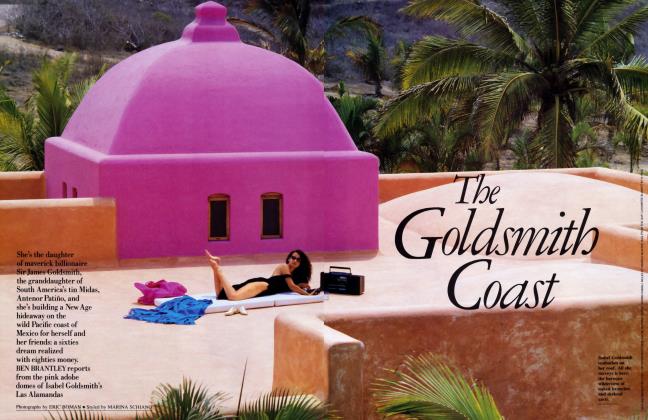

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBARBET'S FEAST

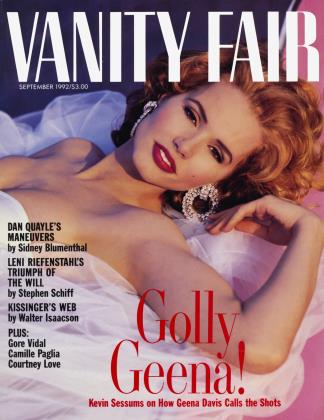

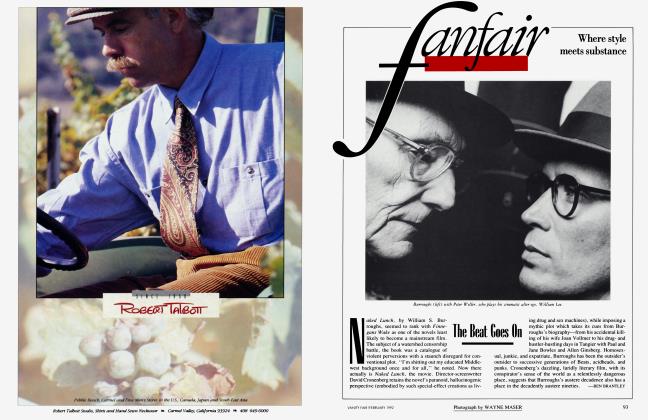

Movies

Why Barbet Schroeder, director of Single White Female and Hollywood's auteur anomaly, goes for the forbidden in art and in life

BEN BRANTLEY

Barbet Schroeder, the nomadic European director now successfully roosting in Hollywood, has a Geigercounter laugh—a dense, ongoing chuckle that speeds up at the first signs of the perverse, the absurd, the outrageous in human behavior. He is a man who, he notes cheerfully, has "kind of a weakness for mon-

sters," and he has devoted his extremely varied, extremely international career as a filmmaker to enshrining the "monsters" of real life—from Idi Amin to Claus von Bulow—with clarity, detachment, and affection.

He himself seems to be happiest in extreme, counterconventional situations. And on the day he takes me driving through the Oakwood ghetto—a gang-dominated neighborhood in Los Angeles near Venice Beach where he spent "the best year of my life so far"—the laugh is in full throttle.

"This was my kitchen!" he says, indicating a comer of an innocuous peach-colored stucco house. "There were some bullet holes in the window.

.. . Here, I found a girl being raped on top of my car. I went and saved her. . . . Here, under my house, is where people were taking refuge after they stole ladies' bags and were sharing the money. My bed was just over that, so I could hear them. After I banged on the floor a few times, they didn't go there anymore."

Other points of interest are annotated with the same, strangely bright avidity: the house next door where the VI3, "the most dangerous gang in Los Angeles," lived (in order to belong, Schroeder says, chuckling, "you had to have killed someone in front of the others"); the location of a fight between a loud insomniac musician and an enraged neighbor which resulted in one severed hand and one dead body; the driveway from which Schroeder's dinner guests routinely had their car radios stolen. "It was unbelievable, " says Schroeder of his year in the neighborhood. "Because there was an exhilaration there. Everything was happening all the time. You never needed television. . . . You always fell asleep to the sound of machine-gun fire."

A tall, big-boned man with closely cropped white hair and the face of a Germanic sprite, Schroeder delivers these observations in a manner that never reads as ghoulish; the tone is fond, observational, and oddly respectful. It makes sense when Jennifer Jason Leigh, one of the stars of Schroeder's current urban-gothic thriller, Single White Female, later describes him as someone who "can seriously go into the dark side of things. . . and enjoy it and have compassion and feelings for this darkness without ever losing himself in it." Or when Nicholas Kazan, the screenwriter on Schroeder's Reversal of Fortune, tells me, "They say God smiles, and the Devil laughs. And there's a touch of the Devil in Barbet, but there's also a wonderful humanity and an understanding." His longtime friend, writer Joan Juliet Buck, describes him simply as "part weirdo, part Boy Scout," adding, "and I trust him implicitly."

Barbet Schroeder moved to the Oakwood ghetto in 1981, after a year in the calmer environs of nearby Redondo Beach, where he soon tired of "the yuppie, the security, the condominiums." It was the period when he was working with writer Charles Bukowski, the maudit chronicler of marginal lives in American society, on the script of Barfly—the movie which would launch him, at last, as a Hollywood director. He shared the Oakwood house with a friend, who, according to Schroeder, was a gambler and occasional swindler who had recently escaped from jail in France and would serve as the inspiration for Schroeder's 1982 French film, Les Tricheurs. Behind the house, the pair set up a chicken coop (in the mornings they collected both eggs and emptied stolen handbags) and created an elaborate garden, modeled on the sixteenth-century gardens of the Chateau de Villandry—"only vegetables," says Schroeder proudly, "but in a beautiful configuration. ' '

The fact of the garden—shaped with recondite European precision—is as important in understanding Barbet Schroeder as his fascination with the violence which surrounded him. The son of SwissGerman parents, and someone who grew up, variously, in Iran, Colombia, and France, he approaches the world with both a Hispanic black humor, which embraces death and danger, and a Cartesian clarity. "He's a person who's not interested at all in morality, but who has a code of behavior that's his own," says Susan Hoffman, the associate producer on Female. "There's not a lot of sentiment. But he goes to great lengths to maintain his connection to that code."

His friend Suzanne Fenn, a French film editor working in Los Angeles, describes him as a person who presents "a strong sense of the primitive" in "a supersophisticated shape that comes from his cultural background. The aesthetic is very codified. But there's a rawness in the ultimate reality. . . . And even though when you meet him you think that what's powerful is his conscious shape, the reality is that his subconscious is ten times more powerful."

Correspondingly, he is a man for whom nothing, as a cinematic subject or a personal experience, is taboo. He has spent his twenty-odd years as a director following his curiosity into what his wife, the great French actress Bulle Ogier, describes as "forbidden zones": the jungles of New Guinea (for the 1972 feature La Vallee) and the state rooms of the then dictator of Uganda (for the revelatory 1974 documentary General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait); the arcane world of sadomasochists (the notorious French feature Maitresse, 1976) and the expensively furnished bedrooms of Sunny and Claus von Biilow (1990's Reversal of Fortune, the critically acclaimed fictionalization of the von Biilow court case, starring Jeremy Irons and Glenn Close).

Whether working in fact or fiction, he brings a nonjudgmental, nearly anthropological quality to all of his films, and shadowy phenomena are examined in daylight with an unflagging empathy. He must, he says, be a little in love with his subjects. He believes the murderous, jovial-seeming Idi Amin was truly evil, but "in a very natural, joyous way. . . . That's the side I like about him, that he was like a wild young elephant." And he admits happily that he could easily identify with Claus von Biilow—the droll socialite—art dealer accused of trying to murder his wife. (Irons has said he modeled certain aspects of his performance on Schroeder.) "We have," he says, "some of the same sense of humor."

"I'm a very faithful man," says Schroeder. "I'm faithful to my wife. I'm faithful to my mistress."

Single White Female—an intensely dark, suspenseful study of a young Manhattan career woman, Allie (Bridget Fonda), who discovers that her new roommate, Hedy (Jennifer Jason Leigh), is appropriating her identity—would seem to be a professional departure for Schroeder. Not only was he working within the context of a corporate studio structure (Columbia) for the first time, but he was also shooting on soundstages, employing a purely fictional script, and making express references to other films in the same genre. At fiftyone, says Schroeder, "it's about time I started exiting life and entering movies."

Nonetheless, in many ways Female retains his sui generis stamp. Though its look is deeply, dramatically stylized— thanks, in large part, to Milena Canonero's production design and Luciano Tovoli's moody cinematography—it also possesses a cool, documentary lucidity which refuses to weigh the film in favor of its obvious heroine. Schroeder says he has tried to "pervert, subvert" the suspense genre with a clinical attention to detail and by forcing the audience to sympathize as much with Hedy, a borderline schizophrenic who gradually slips into murderous madness, as with her more conventional "victim," played by Fonda. ("I like that at the end"—chucklechucklechuckle—"you're sort of rooting for Hedy.") Both characters, he suggests, are culpable in their self-corroborating need for each other, and the movie is really about the dangers of co-dependency. "Because, in the end, if you can't be alone in the world, you cannot be yourself."

The film offers other insights into its creator. Merging with another, alien identity is, after all, what Schroeder has repeatedly aimed for as a director, and he says the line between voyeur and participant is, for him, a nebulous one. It seems especially apposite that this movie should revolve around women's personas. Schroeder is offended by suggestions that the movie is misogynistic, noting he has always felt far more comfortable with women than with men. (In fact, when he's in Manhattan, his favorite nocturnal hangouts are "the clubs with lesbians, young lesbians. . .since I don't like men so much.") And Suzanne Fenn thinks that if Schroeder would see himself in any character in the film "it would be the girl who would want to steal the other woman's identity," adding, "I do think that partly he's nourished by identifying with women.''' Asked if there was something in the idea of "merging" that he would be drawn to, Schroeder, for once, sounds confounded, "Mmm-hmm, mmm-hmm. . .Yes. Certainly that was attractive. But I can't start to analyze myself.''

Fenn observes further that there's a contradiction between "that very polite, male, European quality, with a certain appearance of rigidity," and "the fact he works completely with more the curves of his personality, which are feminine." Several other people I talked to brought up the same idea, noting his refusal to assume a macho, authoritarian posture in overseeing a movie. He is contemptuous of displays of power and is, by all accounts, a gentle, thoroughly collaborative, and—in spite of his obdurate vision of what his films should be— even passive-seeming director who, as screenwriter Larry Gross notes, "allows himself to be seduced by the actors."

There is also a strong current of empathetic eroticism in this attitude—one which many women have been drawn to. Nearly everyone I interviewed seemed to know a woman who had at one point been involved with Schroeder —a novelist, an artist, and, more recently, a Hollywood screenwriter.

"Yes. What can I say?" says Schroeder when I bring this up. "I'm not going to start exposing them, of course." He does say that he believes that sexual passion "can really last only about a thousand days. A thousand days is a nice formula, but actually it's a little less—it's like two years and a half. You see, most relationships start to die or start to change after two and a half years. This is a horrible reality that no parent ever says to a child."

Accordingly, Schroeder believes that the forms of sexual expression can, and should, be manifold. He reportedly once startled a Hollywood industry dinner party by describing a "spanking" seminar he and his girlfriend of that time had attended. And he says that as an adolescent he became fascinated with the sexual-psychology texts of Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis. "I was studying case by case all those perversions. And I came to the conclusion, very young, that if you have only one of those perversions you're a prisoner. You can only have your pleasure in a very special configuration. But at the same time, the intensity of your feeling must be immense. So I decided, I don't want to be a prisoner of just one thing. But I want the intensity. So I want to have them all at the same time. ... Which was, of course, a very intellectual conception. But I started doing my research very early. ' ' And has he succeeded in his goal? "I'm still trying. [Chucklechucklechuckle] I'm still trying."

Nick Kazan, speaking of Schroeder's sexual openness, says, "He may be interested in domination and perversion, but it's out of a love of life and a love of experimentation. . . . There is a sweetness about him. I hesitate to say it, but I think if America could experience all of these perversions with Barbet, they would no longer consider them perversions."

A woman who had a sporadic affair with Schroeder in the early seventies recalls spending a night with him in Cannes and the next evening seeing him on his motorbike with Xaviera Hollander, author of the autobiographical Happy Hooker. "So you realize it's all about total exploration, total freedom. You know, you slept with him the night before, and here he is with Xaviera Hollander. It's not like being dumped for somebody else. And it's not like a guy promising things to women—ever, ever, ever. . . . It's like, Oh, you're a part of it all."

Schroeder believes that sexual passion "can really last only about a thousand days."

This philosophy may not always play well in America, the land of commitment. But Schroeder, other friends agree, is aboveboard from the beginning about his creed of relationships. "If hearts get broken," says one, "and it's kind of cruel to say, it's their own fault." Schroeder himself says he is "not a Don Juan. . . . I'm a very faithful man. I'm faithful to my wife. I'm faithful to my mistress."

Certainly, there have been key relationships which have endured. With Kathleen Tynan, the writer and widow of critic Kenneth Tynan, he experienced what both parties have described as "a great love affair," which began in the early eighties. His relationship with Bulle Ogier—who starred in three of Schroeder's films—dates back to 1969. "Two days after I met her I told her, 'You are the woman of my life,' and it just happened that it was true." This in spite of the fact that both have led very separate lives, with subsets of other relationships, for many years. "For Barbet and me, the seventies were years of love, joy, passion," says Ogier, a small, precise-looking blonde with an engagingly loopy air of exposition. "But you still have to recognize," she continues, explicitly echoing Schroeder, "that a couple can live in physical passion for only a certain number of years. And if it's seven years, eight years, nine years, that's already a lot. . . . One has sufficiently tallied up love to stay in une grande confidence. . . . There remains a complicity." She adds, "And since Barbet lives in a huge number of cities, he has his harem, of course. But I am the queen of the harem."

Does the fact of the harem bother her? "No," she says, shrugging. "We got married last year." This event took place on one Saturday in April in a Las Vegas chapel. As Ogier recalls it, Schroeder announced the night before, "We're getting married tomorrow." And when she said she wanted time to buy a nice dress, he answered, "You leave as you are or we're not going to do it." So she was wed in a much-worn gray pantsuit with the hat, gloves, and bouquet she rented at the chapel. Afterward, he took off for New York, she for Los Angeles. She points out that the marriage still isn't registered in France. When Schroeder asks her if they're going to do so, she answers, "We'll see." When I ask Schroeder why he chose that moment to marry, he answers, "I like to do things differently. So I got married to her at the moment where normally a successful director dumps his wife. That's the rule—look around: they get success, they get separated from their companion, and you suddenly see them on the arm of a new young thing. I did it just to do the opposite."

Although Barbet Schroeder has lived in Los Angeles on and off for more than a decade, he does not consider it his home. Home, he says, is simply where the movie he's making is. Accordingly, he changes residences frequently and keeps his possessions to a minimum. Even the car we toured the city in together, a white Thunderbird, was rented. His wardrobe of monochromatic, minimally detailed shirts and trousers is totally utilitarian, suggesting an especially well-manicured soldier.

Schroeder was bom into itinerancy. His father was a Swiss geologist for American oil companies, and the family moved frequently: Schroeder spent his first four years in Iran, then lived in Colombia until the age of eleven, when his parents separated and his mother took him to Paris. Both his parents are still alive, though Schroeder says he seldom sees his father and thinks that any paternal influence was slight. From his mother, the German daughter of an Expressionist actress and a psychologist who specialized in the art of the mentally ill, he says he imbibed the intellectual legacy of the Berlin of the twenties. He was brought up with no formal religion; today, fond of such pessimistic philosophers as Schopenhauer (whom he also finds very funny), he says his bible was and remains Homer's Odyssey. He thinks he took from it "a lack of guilt."

His earliest memories, of Colombia, are vivid, and he continues to think of South America as his true "emotional culture." Bogota was, during his childhood, the scene of bloody political warfare, compared with which "the Los Angeles riots were a piece of cake." It imbued him, he says, "with an acceptance of danger, and humor about it, all the time." He recalls the scenes of violence he witnessed with a surreal detachment. Rioters setting fire to skyscrapers was, he says, "very impressive visually." Once, he saw a group of six men carrying a refrigerator from a store they had looted. When one of them started complaining, he was decapitated with a machete by the group's leader. The head rolled onto the pavement, but the body continued to stand for "what looked like forever. ... Of course it was upsetting, but it was totally unreal." He was much more disturbed, around the same time, by the first movie he ever saw, Walt Disney's Bambi. "A horrible movie," he says with a retrospective shudder. "Absolutely terrifying."

Transported to Paris just as he was beginning adolescence, he did not thrive in the rigid school system there. Tall, awkward in French, and an alien "from the tropics," he was perceived by his teachers as somehow evil. Although he swears he was blameless, "whenever there was something wrong, I was always suspected," and he was asked to change schools five times in five years. He admits he enjoyed playing with the reputation, deliberately seeking out schoolmates who had been forbidden to speak to him. "It's why I could identify quite well with von Billow," he says, speaking of Reversal's central character, a man who relished his notoriety.

"There's a touch of the Devil in Barbet ," says Nicholas Kazan, "but there's also a wonderful humanity."

Certainly there must have been a knowingness about the young Barbet which his peers couldn't begin to understand. Around the time he was discovering Havelock Ellis, he was also discovering real sex, and at thirteen he seduced a friend of his mother's. "Then I covered the whole range," he says, adding that—for a period—he moved on to prostitutes, since "the supply of older women was difficult." By sixteen he was living with a girlfriend in his own apartment—located in the then violent Algerian quarter of Paris—and no longer required the services of prostitutes. But he retains a deep respect for the profession, adding, "Now, never in a lifetime would I pay a prostitute to have sex with me, because I feel much, much too close to them. The old ones, especially, have the only lucid, clear view of humanity. Their illusions are reduced to a minimum. At the same time, they very often have a great sense of humor." He says that, when in Paris, he still frequents their haunts around the Rue Saint-Denis, because ' ' that ' s where I feel most at home. ' '

The years of Schroeder's initiation into sex coincided with the birth of his obsessions with the decadent poet Charles Baudelaire—whose grave in Montparnasse he visited regularly—and, more important, American movies. He often saw four films a day—he remembers with particular affection the works of Raoul Walsh and Anthony Mann— and by fourteen had decided he would be a director. He began hanging out at the Cinematheque Fran^aise, the unofficial academy of the nouvelle vague of filmmakers, and contributing criticism to the extremely influential film journal Les Cahiers du Cinema. At nineteen, after a brief, unsatisfying stint at the Sorbonne, he volunteered his services as an assistant to the venerated Fritz Lang for a movie to be shot in India. When he got there, he discovered the movie had been canceled, but he stayed on for six months, traveling on a budget of a hundred dollars. On returning to Paris, he worked as an assistant to Jean-Luc Godard (on Les Carabiniers, in which he also played a small part), and, in 1964, at the age of twentytwo, established his own production company, Les Films du Losange.

Losange was created expressly to produce the movies of Eric Rohmer, the Cahiers editor, and its two earliest efforts—the initial films of Rohmer's "Six Moral Tales"—were shot in 16-mm. at costs of roughly $5,000 and $10,000. The third and fourth movies, La Collectioneuse and Ma Nuit chez Maude, captured international acclaim, and the company went on to produce the work of such now legendary talents as Jacques Rivette, Wim Wenders, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, among others. Schroeder acquired a rigorous education in film finance and production, and he remains today a happy exception by Hollywood standards, a man who turns in movies on schedule and close to budget.

In the mid-sixties he married Cornelia Embiricos, heiress to a Greek shipping fortune. The wedding celebrations, which took place on the Embiricoses' private islands in the Aegean, were,. Schroeder says dryly, "blessed by the presence of both La Callas and Greta Garbo. How can you beat that? Plus fireworks, an orchestra... a honeymoon on a gigantic blue sailboat." The couple had a daughter—named Laura, for the Otto Preminger film—but the marriage lasted only two years. "She was extremely intelligent and sensitive and fun," says Schroeder of his first wife, who has since died. "But she had tried many times to commit suicide. . . . That's why this von Biilow story, I know it." Says Suzanne Fenn of Schroeder's portrait of the von Biilow marriage, "I think all his subconscious was in that relationship."

In 1968, Schroeder directed (and cowrote) his first movie, More, a sunsoaked story of fatal love and heroin addiction on the Spanish island of Ibiza—shot principally around his mother's house there and made for $160,000. Schroeder now admits the film was based loosely on an early affair he had had with an addict and was a projection of "what could have happened to me." With its bright, hedonistic surface and subliminal currents of death-baiting and sadomasochism, set off by a Pink Floyd score, the film touched a nerve in late-sixties moviegoers and took in millions at the box office. At twenty-seven, Schroeder became the new golden boy in international cinema.

Bulle Ogier remembers meeting him around this time late one night at La Coupole, the fabled Parisian brasserie, where she was drinking with a group of filmmaking friends, including director Jean Eustache. "He was beautiful, glorious; it annoyed us terribly," she recalls. Nonetheless, when her eyes met the young director's, a definite "coup" occurred. He took her to her mother's apartment, where Ogier was living with a child from an early marriage, and left her at the door, saying he would count to three to see if she would go in or come with him. She hesitated ("I always hesitate"), and, "zoom!—he was back." They spent "a night of passion" at a hotel on the Champs-Elysees, and, not long after, left together for Borneo, where Schroeder intended to shoot a film about a group of hippies in search of paradise.

The movie, La Vallee, which starred Ogier, wound up being made in the jungles of New Guinea and involved six months of arduous travel ("We didn't know what day it was or what country we were in," recalls Ogier) with an extensive cast of tribal extras and a crew which included "some Australian boat captain" as director of production and the gifted Cuban cinematographer Nestor Almendros, who would become one of Schroeder's best friends and remain an enduring collaborator up until his death this year.

In 1973, Schroeder moved on to a very different exploration of civilization and savagery. He had been collecting newspaper clippings on Idi Amin and approached the Ugandan despot with a proposal he could not resist. He told him, "This is very simple. I want to make a self-portrait, so you have to do what you want to show about yourself." The results were astonishing: laughing loudly when asked if he had really said Hitler hadn't killed enough Jews, denouncing a minister in a Cabinet meeting who was found dead two weeks later, and jocularly pronouncing, "We are not following any policy at all," the dictator hung himself with more efficiency than any political analyst could have managed. When Amin heard about the results, after sending "spies" (who Schroeder believes were with the I.R. A.) to a London movie theater, he was outraged. Though he said he didn't blame Schroeder—who he felt must have had "a Zionist in the editing room"—he demanded three crucial cuts. When Schroeder refused, Amin rounded up 150 French nationals living in Uganda and threatened reprisals. "It became dangerous," recalls Schroeder. "I said, 'I have the choice now: is he going to cut some heads, or am I going to cut some pieces of film?' " The cuts were made, but when Amin fell from power, the film was quickly restored to its original form.

"If you don't give me the release paper I need to make the movie," he wrote Menahem Golan, "I will begin sending you body parts in the mail."

Schroeder feels Amin was merely a caricature of "every head of state on this planet," and he was amused by "how other people in power were so attracted by this movie. They all wanted to see it: the Shah of Iran, Mobutu.. ." As the man who controlled the negative, Schroeder told all prospective buyers he didn't sell individual prints, only countries. As a consequence, "I sold Iran, I sold Zaire. [Gleeful laughter] But it was only for Mobutu, and only for the Shah."

With his next film, Schroeder ventured even further into the realm of taboo, adding another dimension to his already controversial reputation. Starring Ogier and the young Gerard Depardieu, Maitresse offered an unflinching look at a professional dominatrix (Ogier) who ritually debases her clients with whips, boots, cages, and hammer and nail. (In the film's most, uh, memorable scene, the foreskin of a penis is nailed to a board.) The movie was fiction, but many of the clients were the real thing, recruited by prostitutes Schroeder knew. Some of these men, he says, could have financed the film "out of their own pockets."

Maitresse was strong meat for most moviegoers (this time, Schroeder refused to make cuts), and it just covered its costs. It subsequently developed a very specific cult. (When Schroeder arrived in New York in the late seventies, he was feted by a group of dominatrices and their slaves—to whom he was, of course, a star—with a banquet in a Japanese restaurant.) But beyond its obvious sensationalism, the movie—with its parallel stories of the "normal" love life of the dominatrix with Depardieu and her professional activities—suggests unsettling correspondences between extreme sexual practices and the masochism Schroeder believes is inherent in any love affair. "It's sex as theater, whatever," he says. "But of course for me, I always have a very healthy, joyous approach to all this." Also utilitarian. He once suggested to a female friend—who was psychically flagellating herself over an ended love affair—that it might be healthier if she compartmentalized her masochistic tendencies. "It was like, Wait, there is a solution to this and it's not therapy, but a form of sexual game playing," she says. "It's rational, and it's totally out of left field." When I ask Schroeder if he considers himself a masochist, he answers, "I hope I'm everything."

All through his career, Schroeder says, he'd been trying to make movies in America, pitching scripts and concepts that somehow never caught the eye of Hollywood. He is now slightly dismissive of his early works, arguing that the directors who were his childhood idols —such as Roberto Rossellini and Otto Preminger—didn't begin their best work until they were approaching fifty. "So I said to myself, I want to make movies, but I will be starting to really function only at that age. In the meantime, I can be more life-oriented and make a movie only every four years and live intensely my movies."

While he was working on his documentary on Koko, a gorilla who could communicate with humans by sign language, in Northern California, he began reading the works of a man who, strangely, would help open the door to American movies for Schroeder. Charles Bukowski was a dark, feisty, and clear-voiced poet and prose writer whose salty tales of the disenfranchised and downtrodden had attracted an international cult of readers. Schroeder found in his writings a kindred sensibility and, after many rebuffs, persuaded the extremely skeptical Bukowski to produce a screenplay, a very autobiographical love story between two alcoholics which would become Barfly.

As always, Schroeder dove deep into his research, hanging out "for years" in the bar-littered bluecollar L.A. neighborhoods of Bukowski's youth, "examining every little comer." He even lived briefly with the writer while he worked on the screenplay, and videotaped more than forty hours of Bukowski monologues, which, shown in brief segments, became a hit on latenight French television.

"In one evening, we were emptying like twelve bottles of white wine," says Schroeder of that time. "I couldn't do that again, and he couldn't either." The two men got along well and have remained friends, although there were some interesting clashes along the way. Schroeder recalls returning home after one sodden evening with Bukowski and receiving a phone call in which the writer accused him of both flirting with his wife and drugging his wine; he would be coming over shortly, he told Schroeder, to kill him. Schroeder's response, he recalls, was " 'Listen, I'll make it easy for you. Because if you come and kill me, you may end up in jail. So I'll write a suicide note. Then you can kill me. This is to prove I didn't put anything in your glass.' He said, 'Well, that sounds like a pretty good answer.' So he calmed down. But then we had another argument, and I told him I was going to bum down his house. And that he believed. So he got really scared."

Barfly would take seven years to get off the ground; moneymen simply found the subject "depressing." Finally, in 1986, the maverick Israeli team of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus of the Cannon group—which was shifting from action-exploitation to art movies—agreed to take on the project, but shortly after that their company ran into deep financial troubles. Schroeder says Golan promised him that if he could come up with other financing for the film Golan would agree to release the rights to it for "only what has been spent so far and no more." But when Schroeder did find a backer, an East Coast real-estate magnate, Cannon asked for an extra million, and it looked as if the deal would dissolve. "That's the point," says Schroeder, "where I became absolutely desperate."

"This is the last place on earth for a film director to live," Schroeder says of Hollywood. "The values of this town are leaked onto you; they're injected in secret."

Susan Hoffman, then an executive with Cannon, paraphrases the letter Golan received at that time: "Dear Menahem, I am so grateful to you for all you have done and for making my film Barfly possible. And I still, no matter what happens between us, want to buy you that dinner in Paris that we talked about. But you must know that this is the movie of my life. . . . And if you don't give me the release paper I need to make the movie, or make the movie, I will begin sending you body parts in the mail. Thank you so much, Barbet Schroeder."

What followed is industry legend. Schroeder staged a "hunger strike" one weekend in front of the Cannon offices, "to prepare myself mentally." On Monday, armed with a fine-bladed Black & Decker jigsaw (he told the salesman it was for cutting precious wood) and a local anesthetic he had stolen from a doctor who had removed his ingrown toenail, he entered the office of Alan Abrams, the Cannon lawyer (Golan was in London at the time), and turned on the jigsaw. "The most painful part was to inject myself with this fantastic painkiller," explains Schroeder. "But it gave me a lot of confidence, the fact that my finger was completely numb. And I was not going to cut a lot, just the very tip, you know..." In any case, he didn't need to. The lawyer turned over the release papers. (In Les Tricheurs, the French film Schroeder had shot four years earlier, the film's protagonist, a gambling addict, fantasizes about severing his fingers, and actually once attempts it. When I recall this to Schroeder, he seems startled. "Yes, he does, actually," he says, shaking his head. "I had forgotten.")

In fact, after further convolutions, Cannon wound up making Barfly and making money on it. Shot in thirty days for a budget of under $3 million and starring Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway, the film reaped ecstatic notices and earned its director the reputation of a man able to steer "difficult" actors to peak performances. After the 1990 release of Reversal of Fortune—which garnered an Oscar for Jeremy Irons and a nomination for Schroeder—the director was firmly entrenched on Hollywood's A list, with the attendant seven-figure fee. He is now a rich man, but when I saw him he was living provisionally in a small, largely unfurnished house, "like an apartment," near Culver City. The more money he has, he observes, "the more I can ignore it completely."

Today, Menahem Golan speaks fondly of Schroeder. "I want you to write that I was the one who discovered the guy," he tells me. And what about the finger incident? "I loved him for that, let me tell you; I loved him for that. It kind of reminds me of myself." In fact, most people who have worked with Schroeder talk about him with nearly unqualified affection, citing his loyalty, his courtesy, his sense of honor, and, above all, his eternal openness to suggestion. He is one of the rare directors who won't change a line in a script without consulting the writer. "Barbet's not interested in being the boss," says Nick Kazan, recalling the Reversal shooting. "From the outset, he would answer actors' questions, and then turn to me and say, 'Is that right?' and I'd say, 'Well, actually, no, it's the opposite.' And he'd say, 'Fantastic. That's even better.'

There was never a flicker of resentment. ' '

He is nonetheless quietly adamant in defending his conception of the overall movie. When stars or producers interfere with that, he says, he invokes his "magic formula": "Get another director." When Rourke insisted he sport a Hawaiian shirt and a tan for Barfly, Schroeder calmly, and sincerely, told him that he wouldn't be able to direct the movie in that case. For Female, he was granted near-total autonomy by the Guber-Peters Entertainment executives then in charge of the production, Michael Besman and Stacy Lassally. But there was one memorable clash, which those involved in it now refer to as "the Hair Affair." Schroeder claims the long-haired, blonde Lassally wanted "to dictate the hair color of the girls [who, in the film, become mirror images of each other]; she wanted them to look like her." A couple of days before production, Schroeder had Leigh's and Fonda's hair cut short and dyed red, without informing the money people of his intentions.

"We endorsed the concept 10,000 percent," says Lassally, who's now at Tri-Star. "It's just that the short hair was never mentioned. It turned out to be one of the most special buttons to the whole movie. [The argument] was just about, when does the financing company discover that? It wasn't that he was right and we were wrong: he was right; we were right; we wanted to know, and he didn't want to tell us. I don't think, to this day, that he understands that. It was the method, not the end result [that we objected to]. "

Lassally praises Schroeder's conscientious involvement with all phases of the film ("He was critical in the marketing") and the fact that he "takes absolute pride in meeting his budget" (a modest—by Hollywood standards—$17 million). She adds, "He's very charming, and he understands the power in a room. He knows who to talk to. I'm sure there are examples of independent filmmakers who never quite get that." Says Female production designer Milena Canonero, "He's certainly not an egomaniac. But he's very Machiavellian, in a good sense; he knows how to pull the cords vis-a-vis the people that think they can manipulate him."

One evening, Bukowski accused Schroeder of flirting with his wife and drugging his wine; he would be coming over shortly, he said, to kill him.

So Schroeder will soon again be directing for Columbia, another psychological suspense film, with Meryl Streep slated to star. Before that, he had hoped to realize a long-cherished project, which echoes his pre-Hollywood roots in film: shooting a movie on location in Thailand from a script by another writer who deals lyrically with lives on the edge, the playwright John Stepling. Schroeder remains suspicious of the industry town which is Los Angeles. "This is the last place on earth for a film director to live," he says. "Not only aye you out of touch with things, but slowly, slowly the values of this town are leaked onto you; they're injected in secret. And those values are extremely tricky."

In spite of these objections, Barbet Schroeder has a prickly affection for Los Angeles and, predictably, has discovered it according to his own map of obsessions. On the day he took me driving, he showed me a lot of his favorite places. We never made it to the German antiques shop whose owner claims to possess both Eva Braun's jewels and Goring's pistol. But we did stop by the Normandie Casino—a gambling hall in the city's Gardena district which Schroeder tries to visit at least once a month. "You're going to see faces," he promised me. "Fantastic faces." The people around the gaming tables were mostly old and sunk into gamblers' hypnotic passivity, with faces as creased and stony as those of Walker Evans subjects. Schroeder circled them quietly, with the entranced, slightly voracious smile of a friendly cartoon shark.

He also took me through the Hispanic neighborhoods in East Los Angeles, which remind him of his Colombian childhood. We strolled through the Mercado, a funky two-tiered structure which is part grocery store, part elaborately decorated restaurants in which mariachi bands play. ("Isn't it great? It's insane.") We dined at a windowless place in the neighborhood with superb Mexican-style seafood. We drove slowly through L.A.'s skid row and the area on the periphery of downtown where Barfly was filmed and where Bukowski once lived.

Schroeder's internal compass is well tuned, and we got lost only once—when he was hesitantly discussing his relationships with women and took a wrong turn onto the San Diego freeway. Many of the areas we visited showed ashy scars from the recent L.A. riots, an event which Schroeder tried to witness, as much as possible, firsthand. ("I love fires.") A man who is fascinated by the cult of Dionysus—and who once journeyed by horseback to a remote section of northern Afghanistan because he had heard that such rites were still practiced there— he found in the riots themselves "a lot of joy and happiness. It was like a big orgy, a big Dionysiac thing. The only problem is that in a Dionysiac context you're supposed to have a beginning and end; it's ritualized. Here the end was a horrible hangover that's going to last for many years."

I said I presumed that Dionysus was his favorite god. "Well, yes," he answered. "But I wouldn't want him to be in control of everything." He added quickly, with a nod to Greek mythology's most civilized deity, "I like Apollo to be there, too."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now