Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBohemian Grooves

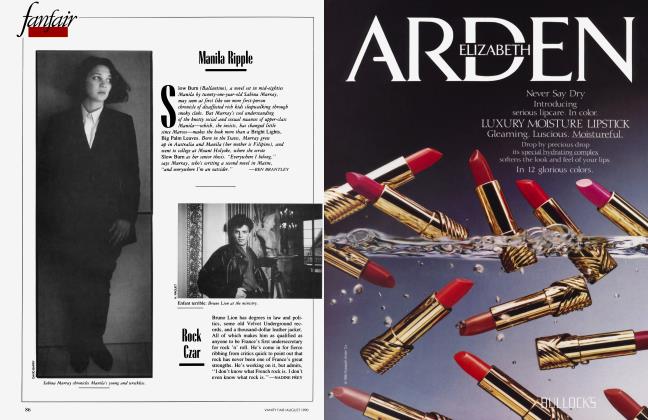

An artist s house is a sort of self-portrait. BEN BRANTLEY views the domestic arrangements of three rising Manhattan talents

At thirty-three, New York painter Donald Baechler—who's spent much of his adult life "camping out" on mattresses in unfurnished rooms—figures it's time to stop living like a student. "You get too old, finally, to sleep on a futon on the floor," he says. "In general, younger artists really live like pigs." And so, by tentative degrees, Baechler is establishing a home.

He's begun trading drawings for furniture with antiques dealers. The bedroom in the Alphabetland apartment he recently took in Manhattan's East Village now harbors a twenties bed-andvanity suite that remains provocatively unassimilated in the bald white space. He can't tell you its specific provenance, any more than he knows where the assorted, slightly battered vintage American pieces in his drawing studio, four floors below, originally came from. He's always collected anonymous art—from prisoners, psychiatric patients, children. Now, he says, he's collecting anonymous furniture.

Previous tenants include Rothko,Gory,Arman, and Sandro Chia.

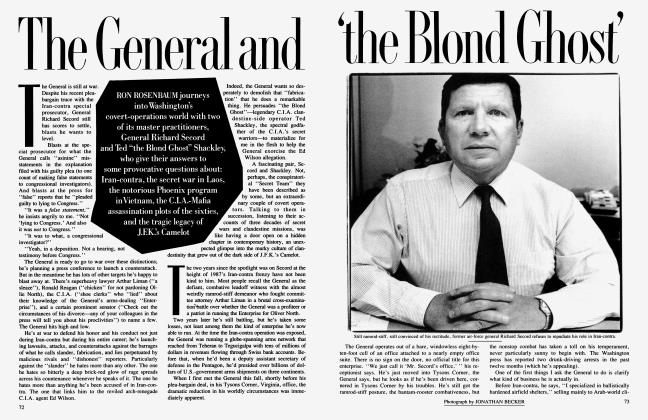

An apartment, of course, can be as expressive a self-portrait as a formal work of art. The young painters shown on these pages—Baechler, Vincent Gallo, and Michele Zalopany—all arrived in New York at the end of the seventies. They are now in their late twenties or early thirties, ages at which lives and styles jell into more finished forms, and transience is exchanged for at least the illusion of stability. Their work, along with that of many of their contemporaries, shares a complicated, ambivalent nostalgia for the past and a taste for found images and objects redefined by new contexts. Now that their art is commanding respectable fivefigure sums (a nine-foot-square Baechler painting might sell for $70,000), the same sensibility is evident in the Manhattan apartments they've finally settled in.

Vincent Gallo left his parents' Buffalo, New York, house, where his mother ran a beauty parlor, at the age of sixteen, as he'd always told them he would. He arrived in Manhattan in 1977, and for a while lived out of his blue '66 Chevelle Super Sport, which contained his stereo and three boxes of canned food he'd stolen during a job in a Buffalo grocery store. He moved on to a twenty-six-dollar-a-week room in a transients' hotel, became a habitue of the Mudd Club, and met such friends as painter Jean-Michel Basquiat and performance artist Ann Magnuson. In 1978 he spent an angst-ridden summer in Europe and discovered he "could make it through each day'' by drawing. When he returned to New York that fall, he moved into the apartment in Little Italy where he still resides.

Initially, he says, he fixed up the place like "a seventy-year-old-bachelor's apartment.. .everything was very old-man-ish, like when you were a kid in the sixties and visited your grandparents' house.'' It consisted of three tiny rooms neatly appointed with small-scale scavenged furniture. In the succeeding years he composed music, performed in rock bands, acted on TV crime shows and in underground films (in Portugal, he says, he's a movie star), wrote poetry, and gradually, realized his paintings were "the most clear of the things I wanted to do.'' His paintings on mottled sheets of metal are delicate still lifes of wine bottles, fruit, and, more recently, flowers. Tersely sentimental, they suggest artifacts from an older civilization, "cultural metaphors,'' as he puts it, "of my own memories.'' After a short-lived marriage in 1986, he took over the apartment above him, gutted the two floors, and proceeded to convert them, by himself, "into my cultural fantasy, the same way I transform an old piece of tin into my idea of a painting."

The apartment, which he completed last year, is a Spartan place, with a dreamlike quality of antiquity. The mostly unadorned walls are of unpainted plaster which recalls oxidized metal; a stark handcrafted staircase connecting the two stories has inwardly angled risers to keep it from being too "suburban"; the furniture is accordingly fundamental-looking—a pair of iron Italian cafe chairs, an eighteenth-century Pennsylvania Dutch cupboard which cost $2,500 but is "the kind of thing if you threw in the garbage it could possibly stay there for a year." There is also a pair of forties Western Electric speakers; a 1958 Ampex tape machine, on which he records and mixes his own compositions (played on a mint-condition 1937 John D'Angelico guitar); a shower with sheetmetal doors; and, in the kitchen, an ironand-porcelain 1948 Magic Chef stove "that kills any other stove." Everything, says Gallo, "has this old, traditional, ancient kind of sensibility, when things were done as good and as simple as possible." Seated happily on a small iron chair, he adds, "People come here and they find my apartment very uncomfortable. They always say, like, 'Where's the couch?' But I'm so comfortable here. I just don't get it."

Continued on page 151

"People always say, like, Where's the couch?'"

Continued from page 104

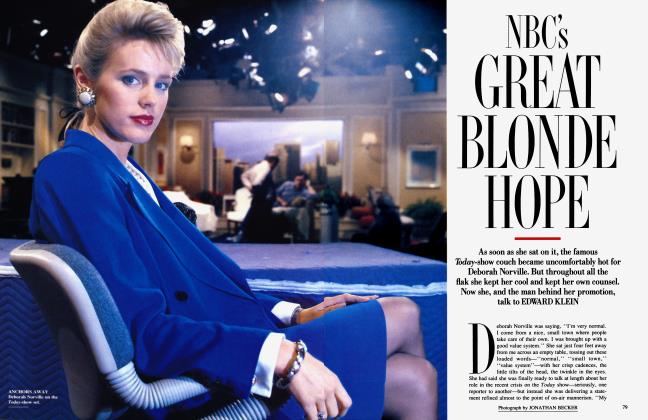

Detroit-born Michele Zalopany came to New York in 1978 as a student at the School of Visual Arts, took a two-and-ahalf-year sabbatical in Italy, and returned to Manhattan to develop the gray-toned pastels, copied from photographs, which she showed in the last Whitney Biennial. "I sort of got kicked out of my house when I was seventeen," she says. "Then I went away to college, and I got married and divorced, and I kept moving and moving, and every time I moved I chucked everything out." Last April, she settled into a sun-drenched apartment in the Chelsea Hotel, New York's classic resting spot for migratory artists and writers. Her rooms' previous tenants include such legendary talents as Rothko, Gorky, Arman, and, most recently, her friend Sandro Chia, who used it for putting up itinerant friends and passed it on to Zalopany.

Zalopany's work (taken from photos of such varied locations as Tiananmen Square and the boardroom of a Boston bank) casts a cool, melancholy eye on architecture and interiors. It both laments a grander, more dignified style lost to time and suggests a distaste for the sort of bourgeois "clutter" she says she grew up with. Her own first "real home" is appropriately uncluttered, with a sparse selection of dark Mission furniture set off by white walls and works by contemporaries like Julian Schnabel, Rene Ricard, and David Robbins. Zalopany, who is also restoring a thirteenth-century villa in Sutri, north of Rome, says she always "wanted to live in a Victorian house," and has partially realized that fantasy at the Chelsea, which was built in 1882. She also likes the neighborly intimacy among the people in the building. "It's like a little trunk of New York, the way it used to be before it became polarized. And it's the environment I like. It has a sort of crumbling elegance. It's not too new."

Baechler, too, is attracted by what he calls "the patina of age." From the time of his first New York shows, in the early eighties, he demonstrated a strong, spuriously ingenuous voice—droll, deadpan, and disturbing—built on simple appropriated images and childlike drawings. More recently, he's worked in collage paintings he describes as "a kind of archaeology," in which scraps of paper—a child's homework found on the street, perhaps, or a fragment of a restaurant menu—and fabric are affixed to the canvas. The furniture and objects in his living and working spaces represent a similar dialogue between disparate recycled elements. "Everything is pretty beaten up," says Baechler of his possessions, which include an extensive collection of used toys. His drawing studio (which he used as his apartment until he recently moved into the larger quarters upstairs) is set up to be "halfway between industry and domestic," evoking an "unrenovated" hotel room, since he discovered, while traveling, that he works well in hotel rooms. In addition to pieces of his own art collection (including Andy Warhol's portrait of him with his finger up his nose), slanted against walls, the room features a handsome, timeworn thirties wooden desk, a hospital supplies cabinet stocked with a forest of toy trees and a cloth potato (gifts from friends, referring to common motifs in his work), and a classic metal-frame modem chair in an advanced stage of disintegration, which he says is "a famous chair in terrible condition; I have no idea who designed it."

He adds dryly that he supposes he should start acquiring some accredited masterpieces. After all, he says, "I'm terrified of dying and having my estate go up at auction and having it all be unknown American furniture."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now