Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

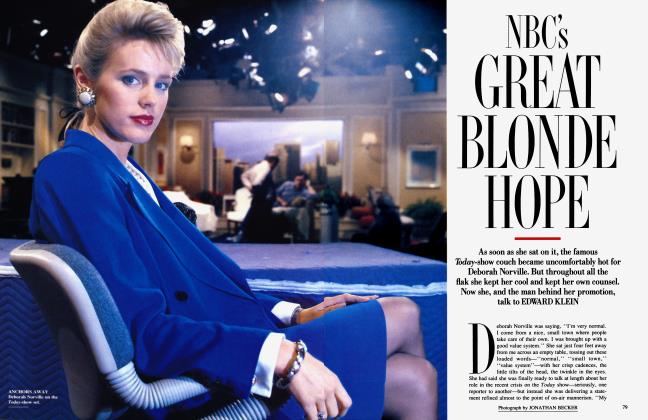

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe General and ' the Blond Ghost'

RON ROSENBAUM journeys into Washingtons covert-operations world with two of its master practitioners, General Richard Secord and Ted "the Blond Ghost" Shackley, who give their answers to some provocative questions about: Iran-contra, the secret war in Laos, the notorious Phoenix program in Vietnam, the C.I.A.-Mafia assassination plots of the sixties, and the tragic legacy of J.EK's Camelot

J.E.K

The General is still at war. Despite his recent plea bargain truce with the Iran-contra special prosecutor, General Richard Secord still has scores to settle, blasts he wants to level.

Blasts at the special prosecutor for what the General calls "asinine" misstatements in the explanation filed with his guilty plea (to one count of making false statements to congressional investigators). And blasts at the press foi "false" reports that he "pleaded guilty to lying to Congress."

"It was a false statement," he insists angrily to me. "Not 'lying to Congress.' And also it was not to Congress." "It was to what, a congressional investigator?"

"Yeah, in a deposition. Not a hearing, not testimony before Congress."

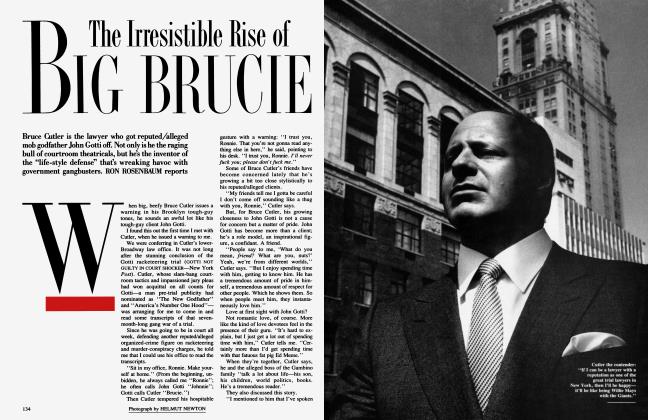

The General is ready to go to war over these distinctions; he's planning a press conference to launch a counterattack. But in the meantime he has lots of other targets he's happy to blast away at. There's superheavy lawyer Arthur Liman ("a sleaze"), Ronald Reagan ("chicken" for not pardoning Ollie North), the C.I.A. ("shoe clerks" who "lied" about their knowledge of the General's arms-dealing "Enterprise"), and a certain prominent senator ("Check out the circumstances of his divorce—any of your colleagues in the press will tell you about his proclivities") to name a few. The General hits high and low.

He's at war to defend his honor and his conduct not just during Iran-contra but during his entire career; he's launching lawsuits, attacks, and counterattacks against the barrages of what he calls slander, fabrication, and lies perpetuated by malicious rivals and "dishonest" reporters. Particularly against the "slander" he hates more than any other. The one he hates so bitterly a deep brick-red glow of rage spreads across his countenance whenever he speaks of it. The one he hates more than anything he's been accused of in Iran-contra. The one that links him to the reviled arch-renegade C.I.A. agent Ed Wilson. Indeed, the General wants so desperately to demolish that "fabrication" that he does a remarkable thing. He persuades "the Blond Ghost"—legendary C.I.A. clandestine-side operator Ted Shackley, the spectral godfather of the C.I.A.'s secret warriors—to materialize for me in the flesh to help the General exorcise the Ed Wilson allegation.

A fascinating pair, Secord and Shackley. Not, perhaps, the conspiratorial "Secret Team" they have been described as ' by some, but an extraordinary couple of covert operators. Talking to them in succession, listening to their accounts of three decades of secret y wars and clandestine missions, was like having a door open on a hidden emporary history, an unexpected glimpse into the murky culture of clandestinity that grew out of the dark side of J.F.K.'s Camelot.

The two years since the spotlight was on Secord at the height of 1987's Iran-contra frenzy have not been kind to him. Most people recall the General as the defiant, combative leadoff witness with the almost weirdly ramrod-stiff demeanor who fought committee attorney Arthur Liman in a brutal cross-examination battle over whether the General was a profiteer or a patriot in running the Enterprise for Oliver North. Two years later he's still battling, but he's taken some losses, not least among them the kind of enterprise he's now able to run. At the time the Iran-contra operation was exposed, the General was running a globe-spanning arms network that reached from Teheran to Tegucigalpa with tens of millions of dollars in revenues flowing through Swiss bank accounts. Before that, when he'd been a deputy assistant secretary of defense in the Pentagon, he'd presided over billions of dollars of U.S.-government arms shipments on three continents.

When I first met the General this fall, shortly before his plea-bargain deal, in his Tysons Comer, Virginia, office, the dramatic reduction in his worldly circumstances was immediately apparent. The General operates out of a bare, windowless eight-byten-foot cell of an office attached to a nearly empty office suite. There is no sign on the door, no official title for this enterprise. "We just call it 'Mr. Secord's office,' " his receptionist says. He's just moved into Tysons Comer, the General says, but he looks as if he's been driven here, cornered in Tysons Corner by his troubles. He's still got the ramrod-stiff posture, the bantam-rooster combativeness, but the nonstop combat has taken a toll on his temperament, never particularly sunny to begin with. The Washington press has reported two drunk-driving arrests in the past twelve months (which he's appealing).

One of the first things I ask the General to do is clarify what kind of business he is actually in.

Before Iran-contra, he says, "I specialized in ballistically hardened airfield shelters," selling mainly to Arab-world clients, many of whom he got to know when he served as the Pentagon's point man for the Reagan administration's bid to sell AW ACS planes to the Saudis.

the ders

"Ballistically hardened means...?"

"Shelters you put over airplanes and airport facilities that can withstand direct hits from certain missiles and free-fall bombs. We were working on contracts to sell to the Emirates. Then we lost it to a European consortium'' about the time Oliver North enlisted him in the Iran-contra operation. These days things seem slow at Mr. Secord's office. There doesn't seem to be anything actually in the pipeline, although the General says he's once again "very close'' to an attractive opportunity. "I'm very close to closing a deal to broker imports of Chilean fruit," he tells me, "mainly stone fruit—you know, peaches and plums." The General strikes me as the kind of guy who will al-

ways be "very close" to a deal; he lacks the smooth-tongued conman glibness of an Ollie North. The General's too prickly, too

martial, to be a good hustler. Aside from the impending stone-fruit deal, Secord depicts himself as debt-ridden, hundreds of thousands in the hole from lawyers' costs. (In addition to fighting the special prosecutor, he's "vigorously" pursuing a libel suit against Atlantic Monthly Press and writer Leslie Cockbum over her book, Out of Control; he's beaten the Christie Institute lawsuit that named him and Blond Ghost Ted Shackley, among others, as leaders of a Secret Team that used assassination and drug money to mastermind evils from the Kennedy assas-

sination to Iran-contra. While the Christie suit was thrown out of court last fall, Secord has got his lawyers pursuing the Christies to make them cough up his legal fees.)

The Iran-contra special prosecutor claims that $1.5 million of profits from the Secord-run Enterprise went to Secord personally, but Secord calls that "a fantasy, it was all frozen, I never got that money." Says he's broke now.

The General has tried some fund-raising efforts on his own, but—let's face it—he's not the charismatic charmer and top-dollar fund-raising phenom Ollie North is. He didn't emerge from Iran-contra the Jimmy Stewart national hero. North did. The General was a much more ambiguous figure. People are still divided over whether to think of him as profiteer or patriot; celebs and politicians never rallied to him the way they did to North. Ironically, one of the only "names" who did rally to Secord's support is the liberal pacifist folksinger Buffy Sainte-Marie, author of the anti-war anthem "Universal Soldier." She watched the General's frontalassault testimony before the Iran-contra committee (he'd marched in unarmed, without the cloak of immunity Ollie North wrapped himself in) and came to believe that here was a basically truthful soldier who was getting a raw deal from the committee because they were afraid to go after Ronald Reagan.

Indeed, the question of the president's role in Iran-contra still lacks a satisfactory answer, as The New York Times recently noted in its account of the Secord guilty plea. The Gener-

al's plea "is peripheral to the central issue in the affair," the Times pointed out, "and seems to underscore how the Iran-contra prosecution has failed to produce an authoritative explanation of who in the administration of Ronald

Reagan was responsible for authorizing the arms scheme [italics mine]." This is no mystery to the Gen-

eral. He's certain he knows the answer to that. "Everything I did was authorized by the president," he tells me. That's why he did it. A

pip-squeak colonel like Oliver North could not order the General around if the General didn't believe, know, the orders were coming from his commander in chief.

He has no doubt about it. He was on a mission for the president, on behalf of his country's national security. He'd been called upon to undertake extraordinary missions before. In fact, he told me about a couple of them at least as extraordinary in their own ways as Iran-contra. I'm thinking in particular of his mission during the Cuban missile crisis and his top-secret "Santa Claus" plan for a commando invasion of Iran. It was in the course of listening to Secord talk about these unpublicized past missions that I began to get a better sense of who he was. And why he didn't understand what happened to him when his final mission crashed and burned. In all the hours I spoke to him the General told only one joke. Actually, technically, he told me about the joke. It's not that he's a humorless guy; he's capable of an extremely dry—to the point of bitterness—deadpan sarcasm. But he never struck me as, you know, a man given to jest. What stayed with me about this particular joke was the way it defined the gulf between the General's world and mine.

"They had eight helicopters. I had ninety-five... I had airborne tankers AWACS. I had it all:'

The joke came up in the context of the General's unusual mission in the Cuban missile crisis. Which was to fly the first wave of the planned U.S. air strike on the Soviet missiles in Cuba. The mission that Kennedy, Khrushchev—and a couple of billion other souls —feared would touch off World War III.

It was October 1962.

War was just a shot away.

Captain Richard Secord was stationed at Hurlburt Field, Florida, as part of an air-commando squadron four hundred miles from Cuba.

As Kennedy demanded that Khrushchev remove the missiles, the Pentagon prepared i the famous "surgical strike" 1 plan: an airborne attack to I blast them out if the Soviet } leader refused to remove them voluntarily.

Down at Hurlburt Field, Secord and nine other pilots were put on round-the-clock standby alert. Their AT-28 "Jungle Jim" prop fighters were armed with napalm rockets. Ready to take off and head for Cuba, the tip of the scalpel of the surgical strike. If global nuclear war were to start then and there—as many thought it might—

Dick Secord was prepared to fire the first shots.

He was thirty then, seven years out of West Point and already one of the most experienced combat pilots in the air force, having flown 285 combat missions in Vietnam in the opening phase of the plunge into the quagmire there. In all I'd read about the Cuban missile crisis, the watershed event of the nuclear age, I'd never read a detailed description of what the surgical-strike plan actually involved. According to Secord it was a two-stage plan. His wing of ten solo-piloted AT-28s would go in low and hit the missiles first. "We were going to mark them," he says, for a follow-on strike by jet fighter-bombers.

"Mark them? What does that mean, mark them?" I ask Secord.

"Lay down napalm and fire rockets into the missile sites," he says. "Then the heavy fighters would come in and knock them out. They wanted us to go in first because they wanted people with combat experience. Only we had it.

The jets didn't have any experience. I thought it was a real sensible plan," he adds.

"And then after you napalmed the missiles they would come in and take out whatever was left?"

"Right. We used to joke—you can imagine what we'd joke about... " He shifts into clipped cockpit-radio tones, imitating what they'd joked about: how after they'd napalmed the Soviet missiles they'd radio back to the combat-virgin jet pilots, " You may bomb my smoke now, fearless leader."

Well, sure, top-gun, right-stuff fly-boys never miss an opportunity to rib one another, and the prospect of post-surgical-strike "bomb my smoke" gloating over the combatvirgin jet pilots must have been appealing as hell. But was that the General's only reaction to the nature of his mission?

"Didn't you talk about your mission being the beginning of the Big One, World War III?"

"Talked of little else," he says laconically.

"What was it like? Weird? Strange?"

"Well, it was, but we were doing a job, we were concentrating entirely on that. We were confident of our ability. This was 1962 and we had overwhelming power. The Soviet Union couldn't stand up to our power at that time."

"But missiles could have flown. Bombs would have—" "Yeah, but they would have been ours. I mean, they would have fired back, perhaps, but Khrushchev didn't have a chance and he knew it."

"Wouldn't Khrushchev have moved on West Berlin?" "At his great risk," the General declares. "At his great peril. We had the power to utterly destroy all the Soviets and they knew it. Knew it better than we knew it." It finally began to dawn on me that part of the General— at least the pure military strategist within him—apparently regrets that he didn't get to complete his mission, even if it had started World War III. Because he has no doubt we could have won a smashing victory and saved ourselves a lot of trouble.

He laughed, a high-pitched laugh, a bit short of— but not far from— — maniacal.

The General downplays his role in the Cuban missile crisis.

"I was only a gnat," he says.

"But the forward gnat," I say. The forward gnat of the apocalypse.

The General was no longer a gnat in April 1980 when the Desert One Iranian-hostage rescue mission self-destructed on the Iranian steppes. He was a major general then, when he became acting commander of the planned second hostage-rescue strike in the aftermath of the Desert One failure. The General was chosen because he had the airbome-special-ops logistic experience required, and because he knew the turf and the enemy. He'd flown missions with the Shah's air force in the war against the rebellious Kurds. In the late seventies he'd headed the Military Assistance Advisory Group in Teheran that was funneling billions of dollars in weapons and advanced technology into the buildup of the Shah's army (all of which promptly ended up in the ayatollah's hands). In effect, he'd have to be running the new hostagerescue mission, the Secord Plan, against an enemy he'd trained and armed himself. '

The Pentagon gave him carte blanche to draw on all the resources of the U.S. short of nuclear weapons. By August 1980, the General tells me, he'd put together a sledgehammer force that was on standby alert to blast its way into Iran and take the fifty-two hostag

How was he going to do it? His plan, the Secord Plan, or, as I've come to think of it, the Santa Claus Plan (for reasons that will become evident), is probably the best indication of the General's signature style as a military planner. No surgical strike, this: the General's preferred instrument was not a scalpel but a meat-ax.

Here's how the General describes the difference between the failed Jimmy Carter rescue plan and his:

''In Desert One they had eight helicopters. I had ninetyfive in the force I assembled. I had something on the order of between four to five thousand men in my immediate force. I had fighter cap over their airfields—with my gunships, if they started to taxi any fighters, we'd destroy them on the ground. I had airborne tankers, AWACS, the entire first wing of the special-ops command under my command. I had it all. At that time there were two battalions of rangers in the entire U.S. Army. I had both battalions in addition to all of those other things. As far as I know, they are the only troops in the world trained for night airfield assaults. That was the battalion that took Grenada, those were my men. My preference was for direct assault. Nothing fancy."

''Just go in there?"

''Just like Santa Claus," he says.

"Just like Santa Claus in his sleigh?" I say, not quite seeing the analogy between Jolly Saint Nick and the Secord Sledgehammer over Teheran.

Upon reflection, though, the analogy becomes crystal-clear. Santa, after all, does make use of a nocturnal airborne delivery system, and indeed Secord's plan called for his sledgehammer commando force to drop right down the ayatollah's chimney and come out blasting. Secord is so breezily sure of the Santa Claus Plan— I can hear him briefing the president confidently and persuasively—that I almost don't ask the obvious question, but after a pause I do.

"And once you're in there, how do you know they're not just going to kill all the hostages as soon as they hear you coming?"

"It's unlikely," he says. "These are pretty cowardly people. If they killed them [the hostages] they were going to go V.F.R. direct to see Allah."

"V.F.R. direct? What does that mean?"

"It's a fighter-pilot term. It means no instrument flight, nothing. Just going straight to Allah."

He says his mission wasn't going to go forward until they knew the hostages were in three or fewer locations. There had been a moment—the "Eureka Briefing"—when they thought they'd gotten such intelligence, but it turned out to be false. But given good intelligence, the General had no doubts he could have pulled it off.

Still, his feeling that the hostage keepers wouldn't kill the hostages for fear of "going straight to Allah" seems to ignore the fact that, for religious extremists, going straight to Allah might be regarded as a blessing and incentive to kill the hostages, if they felt it served the ayatollah's will.

"It's a judgment call," Secord concedes. "It's arguable. You always recognize the distinct possibility that the people you're trying to rescue may get killed and hurt. I think the people who have been held for so long in Lebanon, for instance, would certainly welcome a rescue attempt. I mean, I think 1 would, rather than the living death of it."

t~ c~ The Kennedy brothers brought an erotic ardor to Third Option solutions.

Iran-contra has been a kind of living death for the General; he's been hostage to the crisis for five years now, two when it was secret and three after it broke. But despite the ordeal he still has no doubts about his conduct. Not only that the whole thing was "authorized by the president," but that it was not a crackbrained illicit scheme but a Good Plan, another "sensible plan."

A plan that would have worked. That's working even now, the General believes. He contends that the much-scoffed-at "Iranian moderates" did exist. Believes in the armsshipment "opening" to Iran. Believes history has already vindicated him in the recent triumph of the Rafsanjani "moderate" faction against the "hard-liners" in Teheran.

Yes, he tells me, the whole thing "might still have worked"—he might have been able to pull it off, get the hostages in Lebanon back—"even after it became public." In fact, the General thinks the whole tragic farce all came down to one heartbreaking moment | when—if he'd only been able to grab the phone away from Ollie North in time and get on the line with Ronald Reagan—the whole thing could have been turned around.

The pivotal moment came on November 25, 1986, when Reagan's attorney general, Ed Meese, had just gone on television to declare he'd discovered the Iran-contra "diversion" and the entire administration from the president on down was shocked—shocked!—by it all. A few hours later, the General was in a hotel room with Oliver North; North was on the phone with the president, and the General was signaling frantically to put him on the line. If only he could talk to the president, the General thought, he might save the mission from self-destructing. But in fact by the time North put the phone in his hand, the line had gone dead. Ronald Reagan had rung off, and thereafter his aides erected a wall around him to prevent the General from getting through.

"What would you have said if you had gotten the president on the line in time?" I ask the General over lunch one afternoon at a place called Twenty-One Federal in downtown D.C.

"I would have said, 'Mr. President, this is Dick Secord—you know, General Secord. One of the principals in this controversy. This is insane. I demand to see you immediately.' "

"And what if he said,

[ 'Come right over'?"

"I would have been there in twenty minutes. I would have said, 'You're badly advised and a lot of people are going to be hurt.' That's what I would have said. What they did was take a covert operation and turn it into a scandal."

He would have had the president tough it out, keep the now overt covert operation going. "It still could have worked," we could have had the hostages home, the General maintains. "Instead, what they did by appointing the Tower Commission was like calling in artillery fire on your own position after the enemy has left."

The General says they turned a covert operation into a scandal, but in fact covert operations have a habit of turning into scandals all by themselves. Conversely, people who get caught in scandals have a habit of claiming they were actually involved in a "fully authorized covert operation" to cover their tracks. The famous "smoking gun" statement in the Watergate case was Richard Nixon's self-taped admission that he ordered the F.B.I. to cut short its investigation of the break-in at Democratic Party headquarters because it might expose a sensitive "C.I.A. covert oparation"—when it actually threatened to

expose him.

But the covert-operation cover story cuts both ways: it's a double-edged sword and the General himself has been wounded by it in the Ed Wilson affair, a wound that seems to cut deeper than any other.

Ed Wilson was an ace secret operative, "a hero," the General says, of the clandestine world, for the supersecret operations he conducted throughout the world.

Then something happened. He turned. He became a renegade. Not a K.G.B. mole but a demented capitalist. He resigned from the C.I.A. and began merchandising his Agency connection shamelessly to get lucrative armsshipping contracts. The whole thing blew up in 1980 when Wilson's multimilliondollar dealings with Muammar Qaddafi were exposed. He'd provided the Libyan dictator and bankroller of terrorists with tons of C-4 terror explosives and other deadly materiel. All along Wilson claimed that his dealings with Qaddafi were authorized and monitored by the C.I.A. After his conviction (and a fiftytwo-year jail sentence) Wilson expanded his claims: he said that then deputy assistant secretary of defense Dick Secord was a "silent partner" in one of his multimillion-dollar arms-dealing enterprises.

Continued on page 126

Continued from page 77

Secord's skyrocketing career was grounded by the investigation that followed. He was suspended from the Pentagon by Caspar Weinberger, then reinstated by Frank Carlucci. He's never been charged with anything on the basis of the Wilson allegations, but he's been tarred by them. In fact, the Wilson taint was the source of his trouble in the Iran-contra affair. Early on, while the resupply effort was still secret, rival contra operative Felix Rodriguez denounced Secord to George Bush aide Donald Gregg as part of the old Ed Wilson crowd. The suspicion of venality from an Ed Wilson link is probably what prejudiced the Iran-contra committee against Secord's claim of pure patriotic motives and led to Arthur Liman's hammer-and-tongs attack on the General on national TV.

The General can barely contain his rage when the subject of the Renegade is raised. I ask him about the Rodriguez claim that he was part of the old Ed Wilson crowd.

"Well, that's a laugh," he says, mirthlessly. "I'm glad you brought that up. You know, I didn't work for Ed Wilson. You know, I was exonerated."

The General is bitter about the Wilson slur. He's successfully sued a Wilson associate for slander for going on 60 Minutes and claiming that the General was one of Wilson's "silent partners." (The milliondollar slander judgment was awarded to the General by default because the Wilson associate, now in the Federal Witness Protection program, refused to drop his protective identity to show up in court.)

But a deeper reason for his outrage about the Wilson link, I believe, is that Wilson the Renegade with his Qaddafi connection is almost a. demonic parody of—or parallel to—the General's Irancontra role. Wilson sold explosives to Qaddafi; Secord sold rockets to Khomeini. Wilson says his was an authorized covert operation; Secord says his was the real authorized covert operation.

Which is perhaps why he sent me to see the Blond Ghost. There's no better expert witness in the world on covert operations, authorized or unauthorized, than Ted Shackley. And Ted Shackley too has been unjustly tarred for his association with Ed Wilson, the General says. The Blond Ghost might have been chief spook, head of the C.I.A., right now if it hadn't been for whispers about him and the Renegade.

"Go see Ted Shackley," the General said that afternoon at Twenty-One Federal. "He'll set you straight. You know, the Christie suit singled him out as one of the arch-criminals of all time, an evil genius. But he's a nice man. Call him up. Tell him I sent you. He'll talk to you."

I had my doubts about that. The Evil Genius/Nice Man—revered as a god by some, reviled as a Kurtzian Heart of Darkness figure by others—is one of the single most fascinating behind-the-scenes figures in the secret history of our times. But as far as I knew, the man known as the Blond Ghost, the godfather of secret warriors, confided in reporters less often than John Gotti.

In the course of his rise to number-two man in the C.I.A.'s clandestine "dirty tricks" division, Shackley had run not just covert operations but whole secret wars for the C.I.A. from the early years of the Kennedy administration. As torchbearer of the Kennedy brothers' passionate romance with counterinsurgency, covert action, "special operations," the Ghost's presence had been felt with deadly force in Cuba, Laos, Saigon, and Chile, to name a few places.

Indeed, you could look upon him, like the General, as one of the last surviving knights of J.F.K.'s Camelot. And not just rusting in his armor, according to some. His legend as a clandestine operator was so potent that in 1987, nearly a decade after he'd left the C.I.A., he was said by some to be the ghostly "father" of the Iran-contra covert operation.

The next morning I tried the number the General had given me for Shackley. It turned out to be the office of his international risk-assessment consulting firm, Research Associates International.

"Dick Secord says I should go see the evil genius face-to-face," I told Shackley. "I'm trying to separate the fact from the fiction about you two." He laughed, a high-pitched laugh, a bit short of—but not far from—maniacal. It seemed to be provoked, at least ostensibly, by my line about separating fact from fiction.

He told me he'd get back to me. First he wanted to do some checking on me. He didn't say that, but he admitted it later. He admitted a number of surprising things later.

Shackley called me back at my Washington hotel on Friday the thirteenth, the day of the 190-point market plunge. He'd be willing to see me the following morning. He'd be working in his office all day Saturday dealing with his overseas clients "in the oil-producing countries," as he put it. They would all be demanding to know whether to pull their funds out of the U.S. Whether the market would crater Monday morning. The Evil Genius/Nice Man gave me an address in a high rise across the Potomac in Rosslyn, Virginia. There would be one restriction on the interview, he said. It would be on-the-record, I could take notes—but there could be no tape-recording.

He had to take precautions, Shackley explained. There had been dirty tricks played on him in the aftermath of his being named a defendant in the now dismissed Secret Team lawsuit. There had been break-in attempts at his office; there had been impostures, people posing as reporters for antagonistic ends. There could be no tape-recording because he didn't want to risk the tape's "ending up in some Christie video"—referring to the various Secret Team videos which Christie crusader Danny Sheehan has used to whip up a fund-raising frenzy among the Hollywood left.

Rosslyn, Virginia, is a spooky place on a Saturday morning. A thick cluster of supercontempo high rises perched like birds of prey within reach of the Capitol and the Pentagon. It's virtually deserted today: all the beltway bandits, procurement-consortium consultants are drinking Bloodies at brunches in the Virginia horse country.

Security is tight in a low-key way at Shackley's high rise—despite, or because of, its apparent vacancy. A separate, privately keyed elevator takes me from the twelfth floor to the penthouse office suite of Research Associates International, where a security camera focuses discreetly on me before the door is opened by Ted Shackley himself.

No longer blond, the Ghost is graying these days; but he's still pale, spectral. Not the shocking pallor of legend. The Blond Ghost nickname, the mystique of the dead-white pallor seem to date back to Saigon, when Shackley was chief of the massive C.I.A. battle station there, from 1969 until 1972, and was said to roar around the streets of the city with a phalanx of motorcycle escorts looking "like a proconsul," making the Empire's presence felt. "More power than a god" is how an awed Felix Rodriguez described Shackley in Vietnam.

Another C.I.A. operative who knew Shackley in Saigon once described his ghostly appearance: "Tall, thin, real white skin, real white. ... He never went out in the sun, man. He never went out in the sun."

These days Shackley looks less, well, mythic. These days he presents the dyspeptic mien of a harried academic on a New England campus in his loosely hanging tweed sport coat, high-water pants, and the open-collar shirt of weekend Wasp informality. Less like Mr. Kurtz than a bilious Cheever melancholic. There is an air of being besieged about him, yes. Perhaps it's the pressure to come up with the right call on the market for his foreigncapital clients before Monday morning.

But there's another sense in which he seems besieged. Not so much by the dirty tricks that followed in the wake of the Christie suit, but by what must have seemed to him a profoundly dirty trick played on him by history. On him and his fellow enlistees in the Camelot crusade. It had started with a kind of idealism. The use of counterinsurgency, clandestine wars, covert operations—"the Third Option" between overt war and diplomatic inaction, as Shackley called it in his book of that title—was going to be the lean, mean, pragmatic action arm of liberal democracies. The way to fight Communist insurrections in the Third World was by winning the hearts and minds of the peasants. In most cases what it came down to was counting their bodies. And now with the idealism gone, the hopes dashed, Shackley is called upon once again to defend Camelot's twisted legacy.

He ushers me into his command post, a spacious office featuring beveled-glass structural walls on two sides, and a dramatic view of the District spread below us.

"My clients are mainly from the twenty-two oil-producing countries," Shackley begins by explaining. "But the focus of Research Associates International has shifted recently," he says, "as the global petroleum market has shifted from wet barrels to paper barrels."

"Wet barrels to paper barrels?" "The oil market is no longer primarily driven by real-world market conditions of supply and demand—wet barrels—which calls for political and economic intelligence. Instead it's increasingly driven by futures-index trading—paper barrels—of what we call 'the Wall Street refiners' like Salomon Brothers."

So Research Associates has shifted more to executive security, he says. Protection. If you're a brokerage exec going to meet an Arab oil client in a Pacific Rim venue, for instance, Research Associates will check out the likelihood of the Arab's being a terrorist target, make an assessment of local security, and tailor a security-system package to the intelligence as well as provide the personnel, i.e., bodyguards.

Shackley's telling me this from behind the vast desk that appears to be part of a suite of newly minted Pacific Rim Consultant Victorian furniture. (It feels as if we could be in Singapore or Abu Dhabi, which I think is the point.)

The setting conjured up for me Out on the Rim or one of those other Ross Thomas novels about dicey doings in the international-consulting game among exgenerals, ex-intelligence guys, arms dealers, and offshore bankers. And there was about Shackley in this setting, with the talk of wet and paper barrels, a whiff of my favorite Ross Thomas character, "Otherguy Overby." Otherguy got his nickname from the way, whenever some international house-of-cards deal collapsed, he'd always be the one to say it was "the other guy" who ran away with the Swiss-account numbers—when he wasn't being somebody else's other guy.

Not that there's anything bogus about Shackley's risk-assessment business. (Indeed, he surprised me that Saturday by telling me he was advising his foreign clients to keep their money in the market, which I thought at the time was a foolish, certainly risky call for a risk-assessment consultant, but which turned out to look remarkably prescient, a tribute to his intelligence, of one sort or another.)

But it's the Otherguy ambiguities of international-consultant culture that are at the heart of Shackley's explanation of why—even though others might have linked him to renegade terror-bomb supplier Ed Wilson—in fact there was no such link.

"Wilson was a great salesman, a great name-dropper," Shackley tells me. "You know the type, always leaving the impression he was your best friend. We know he was saying this kind of stuff, that he was a big buddy of Ted Shackley."

So some people might have gotten the wrong idea. It's true, he says, he used to visit Wilson's grand estate in the Virginia horse country; their wives were social friends. And it's true that while Shackley was still in the C.I.A. he'd allow Wilson to chat him up about the international arms trade, because one of the Agency's big concerns in the late seventies was locating the vast store of arms the U.S. left behind in Vietnam after the fall of Saigon. Shackley thought Wilson might know where these missing arms might turn up. But otherwise they had no official relationship, he insists, and after he left the C.I.A. and Wilson got in bed with Qaddafi, he had no knowledge of the terrorexplosives trade and no business relationship with the Renegade, nor did Secord. And, Shackley insists, he was never a consultant to the Secord-run Iran-contra Enterprise.

Since we are on the subject of Iran-contra I ask Shackley about the allegation that he was the real "father" of the whole Iran-contra affair. (I thought I would take the opportunity to get the Ghost on record on as many of the allegations swirling around his name as I could.) There's a bit of Otherguy in his response to the secretfather allegation. According to Shackley, the whole mistaken notion about him arose because "as part of my business I monitor developments in the oil-producing countries and I had a dialogue going" with a certain Iranian General Hashemi, former head of the Shah's secret police, a man said to have excellent contacts within Iran. In November 1984, General Hashemi persuaded Shackley to meet him in Hamburg, where Hashemi introduced him to the now notorious con man/fixer Ghorbanifar. Who, Shackley says, happened to make "a flip comment" about the Lebanese hostage situation, a flip comment that made reference to the tractors-forprisoners exchange deal the U.S. had made with Castro for the return of the Bay of Pigs prisoners. Since one of the Lebanese hostages of the pro-Iranian Hezbollah was a high-ranking C.I.A. agent named William Buckley, who once worked for him, Shackley sent a memo of the Ghorbanifar conversation and the "flip comment" about a deal to the State Department when he got back from Hamburg.

"They told me, 'We're not gonna do anything about it.' That was in December '84." Six months later at lunch with National Security Council consultant Michael Ledeen, Shackley says, he mentioned the Ghorbanifar "flip comment" and—at Ledeen's urging—gave Ledeen an update on Ghorbanifar's view that a deal might be done.

But, Shackley insists, it was the other guy—Ledeen, not he—who pushed the idea on the National Security Council. It was Ledeen's memo, not his, that got the deal under way, got the Israelis and North into it. He seems to think this clearly establishes that he wasn't the father of Irancontra.

"Imagine my surprise," he tells me, when a reporter called him after Iran-contra broke and asked him if his memo to the State Department was the origin of it all.

" 'Oh my gosh!' " he says he exclaimed to the reporter. "I hadn't put the two together." He claims he's suffered "a nightmare of grief and aggravation from this apocryphal" father-of-Iran-contra charge, which he feels he's conclusively refuted.

Strangely, though, the Iran-contra committee's final report makes what Shackley calls a "flip comment" sound much more explicit: "At one meeting on November 20 Ghorbanifar told Shackley that for a price he could arrange for the release of the U.S. hostages in Lebanon through his Iranian contacts." Strange, because in a footnote the committee identifies the source of this version as "Shackley interview 2/27/87." Indeed, even Shackley's version to me makes it sound as if he might have planted both the idea of a trade and the name of the Iranian "first channel" in Ledeen's mind. Perhaps he didn't actually father Iran-contra; maybe he just stepfathered—or godfathered?—it.

There's also a bit of Otherguy in Shackley's response when I ask him about the C.I.A.-Mafia assassination plots against Fidel Castro that the Church committee exposed in the 1976 Senate hearings. Shackley had been chief of the C.I.A.'s Miami station in 1962, running the no-holdsbarred C.I.A. secret war against Castro, the "Kennedy Vendetta" that followed the Kennedy humiliation of the Bay of Pigs.

"The C.I.A.-Mafia plots," I put it to Shackley directly, "myth or reality?"

"There was a dialogue, yes," he says carefully. "But I was not a dialogue partner. ' '

Not a dialogue partner? "Were you aware it was going on?"

"No."

"Was it authorized?"

"The guy who was dealing with it was my superior. It was not in my purview."

"Who was the superior, the dialogue partner?"

"William King Harvey. He was the one who would have had approval for it. He was in direct contact."

A remarkably candid admission of intelligence failure here, it seems. The Ghost is saying that as C.I.A. chief of station in Miami he was utterly unaware higher-ups in the Agency were coming down to meet with Mob guys in the Fontainebleau Hotel to plan the assassination of Fidel Castro and to pass them poison pills to do it. (The Church committee found that there was more than just a "dialogue" with the Mafia and that in addition there was a series of non-Mafia C.I.A. assassination schemes.)

But, as he says, he was busy. Busy running a secret war which, if anything, managed to consolidate the Castro regime and which, according to Taylor Branch and George Crile in their study of Shackley's war, "may have persuaded Castro to welcome Russian nuclear weapons in Cuba as a means of guaranteeing his own survival."

On to Laos. Here it's not precisely the other guy, it's the other warlord, who's to blame in the Shackley version. In Laos the long-standing charge has been that the C.I.A., at the very least, countenanced opium growing and smuggling by Laotian warlords who were its tribal allies against the Communists. The Ghost really galvanizes himself into action when I ask him about the opium charges. First he calls out to his wife in the outer office. A sturdy, dignified woman with a steely-gray bun appears, and Shackley asks her to bring me a copy of the Senate-committee report that he claims "cleared" the C.I.A. of the opium charges. Then he leaps up from behind his desk and begins searching the office for a proper map of Indochina. Finds one, and brings it over to the couch where I'm seated, spreads it out.

To understand why the opium charge was false, he says, he first has to explain to me the disposition of forces in the twofront secret war he was running as C.I.A. chief of station in Laos. Once again I feel I'm being briefed by a master. At last we come to Vang Pao, the Laotian warlord who was closely allied to and supported by Shackley's C.I.A. battle station in Laos, and who has been the target of opium-trade accusations. "Vang Pao," says Shackley, "was actually commander of Military Region 2 here in northern Laos, the Plaine des Jarres area in the center. Over here in the West is where you see the Golden Triangle opium-growing area. Which was a different military region under an entirely different commander. Vang Pao was not in charge in the Golden Triangle area." It was the other warlord who was in the poppy business.

Shackley's wife returns.

She seems embittered by her husband's having to defend himself all the time. "This is the 50-millionth copy I've made of this," she says as she slaps the Xeroxed pages of testimony onto his desk and exits.

Shackley shows me the committee testimony that "cleared" the C.I.A. (I didn't have a chance to read it then. When I did look at it more closely later, it was not as conclusive an exoneration of the C.I.A. as the Ghost seems to think it is. The committee report quotes the C.I.A.'s own inspector general as having asked C.I.A. personnel who were stationed in Laos whether they knowingly abetted opium smuggling. They denied it, and the inspector general accepted their denials. But the committee investigation does seem to suggest that controls weren't airtight.)

When we come at last to Vietnam and the notorious Phoenix program, Shackley doesn't deny he was involved. He defends the Phoenix program. But he does insist that once again this is a case where not he, but another guy, is the real "father" of the program. The other guy being, in this case, the man they call "the Blowtorch."

Phoenix remains one of the most controversial and hotly disputed episodes in the whole tragedy of America in Vietnam. It's been attacked as a massive "assassination program" that claimed 20,000 to 40,000 Vietnamese victims. It's been defended as the single greatest success of the American "pacification" program in Vietnam, the program that would have won the war if only we had cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos.

Shackley is not ashamed of it at all, he says, but once again there is the question of paternity. He does seem rather insistent that I get straight that he didn't father it.

"I want to put that to sleep once and for all," he says. "I was not the father of Phoenix. The Christies have long claimed I'm the father. I'm not."

"Who is the father?" I ask.

"Ambassador Komer. Bob Komer. You can go ask him, he'll tell you."

Ambassador Bob "the Blowtorch" Komer, as Henry Cabot Lodge dubbed him, was L.B.J.'s special deputy to Vietnam, charged with getting the liberals' dream of a hearts-and-minds pacification program off the ground. (It's often forgotten how many of these dark episodes were dreamed up by liberal "best and brightest" types.)

Phoenix was about pacification, not assassination, Shackley insists. About intelligence evaluation and assessment. To explain the difference between an evaluation program and an assassination program he uses the example of the killing of a hypothetical Vietcong cadre he calls "Ron Rosenbaum."

"Phoenix was targeted against the Vietcong political-military infrastructure in South Vietnamese villages. The first task was to identify the members of the infrastructure. You know, they were great ones for using aliases—for instance, you, Ron Rosenbaum, might be a member of the VC," he says somewhat pointedly. "But you might go by the alias Tom Smith, and have four other names, and we want to know whether there were one or five of you. Then we'd locate where you are, which village, which house, and have the South Vietnamese police go out. And if they found good old Ron, they'd arrest him, detain and incarcerate him for questioning. Now, if good old Ron grabbed his trusty AK-47 when they came for him, they were authorized to return fire. As a result people got killed—on all sides."

Former C.I.A. chief and onetime Phoenix administrator William Colby has testified that about 20,000 alleged VC cadres died as a result of these deadly visits to their villages.

But were they all the Enemy? One charge against Phoenix is that the South Vietnamese authorities—in order to meet the quotas the Americans set for Phoenix—would fill jails (the notorious "tiger cages") and graves with personal enemies, innocents who failed to pay bribes to the list-makers, non-VC dissidents.

But the C.I.A. was not responsible for these deadly mistakes, Shackley says, because it just collated the lists. "We did not have operational control over Phoenix," he says. It was the other guys, "the South Vietnamese military and police, that did the shooting. We did collecting, collation, we were the evaluation mechanism," he says. "Assassination was not part of our charter. ' '

The essence of the Ghost's style in Vietnam was numbers, lists, and quotas. Felix Rodriguez recalls that about Shackley in Saigon: "He had a reputation as a tough guy, very results-oriented, very rigid and ruthless in an intellectual way. He also had a reputation for levying requirements on subordinates that could be measured or quantified. For example, X number of intelligence reports about X number of penetrations, with X number captured and X number killed, was how he liked to see things submitted. The figures made it easier for him to deal with the bureaucrats back at Langley."

And how does a results-oriented guy judge the results of his career as a whole, of the two decades since the Bay of Pigs, during which he was running secret wars and covert actions for the Agency?

Like the General, the Ghost is a man of few, if any, doubts. He sees the record of his Third Option methods as one roaring success after another.

In his book, summing up what he's learned, he tells us flatly that "our experience over nearly two decades in such diverse areas as Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, the Philippines, Zaire, and Angola proved that we understood how to combat 'wars of national liberation' " with the Third Option methods he recommends.

Cuba, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam—successes?

There's a black wall in Washington, D.C., with 60,000 names on it, the names of military men who died vainly trying to make up for the failure of Third Option tactics in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

A more skeptical view of the results of the results-oriented Ghost's career can be found in former Wall Street Journal reporter Jonathan Kwitny's book The Crimes of Patriots, in which he observes that, "looking at the list of disasters Shackley has presided over during his career, one might even conclude... a Soviet mole probably could not have done as much damage to the national security of the United States with all his wile as Shackley did with the most patriotic of intentions."

Toward the close of our nearly twohour-long conversation (I would have gone on, but he cut it short before I could get to Chile, Australia, and the rest), I try to get the Ghost to step back a bit and put Third Option operations from Cuba to Iran-contra in historical perspective. See if he'll talk about the origin of the counterinsurgency gospel in J.F.K.'s Camelot. Because it's my view that the real Otherguy, the ultimate historical Otherguy, in all those operations is John F. Kennedy with his deadly obsession with covert operations. (I suspect J.F.K. liked them because they were as sexy and dangerous and secret and illicit as his own covert liaisons with gangster chicks like Judith Exner. "Doesn't it all go back to J.F.K.?" I ask Shackley.

Shackley quibbles a bit about J.F.K. as the intellectual author of Third Option theory. He traces it to a series of theoretical "articles in classified journals in the late fifties" that argued for an American response to Third World insurrections modeled on the successful British counterinsurgency program in Malaysia.

But he concedes that J.F.K. was the effective godfather of the Third Option.

"It took on a greater sense of urgency when Kennedy came to power. J.F.K. reached out and embraced the Special Forces and the like." Secord too says his career was shaped by J.F.K.'s embrace. "It was the strategy of the time, and I was the right age," he tells me.

" L1 mbrace" has just the right connotaIJ tion of the erotic ardor which, by all accounts, the Kennedy brothers brought to Third Option solutions. Some might call that embrace a fatal attraction, considering the body count from the Bay of Pigs to Iran-contra and the results thereof. Maybe America will never be really good at performing dirty tricks on foreigners, and maybe it's to our credit that we're bad at it.

Ever since my encounters with the General and the Ghost, I'd been looking for a way to put extraordinary figures like Secord and Shackley in perspective. (To me the things they admit are far more astonishing than any Secret Team conspiratorial fabric woven about them.) Finally I found myself rereading Graham Greene's 1955 Vietnam novel, The Quiet American, and discovering in Greene's gung ho idealist American, Pyle, an eerily prescient resemblance to the Ghost.

Pyle's the American agent who gets a fanatical gleam in his eye at "the magic sound of figures: Fifth Column, Third Force... " Pyle falls in love with a Vietnamese girl named Phuong, which is Vietnamese for Phoenix, the all-seeing bird. His love for her brings destruction, of course, like the American "love" for Vietnam would. Greene's epitaph for the Quiet American could be the epitaph for the General, the Blond Ghost, and all the rusting knights of Camelot:

"I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now