Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SCENT OF MONEY

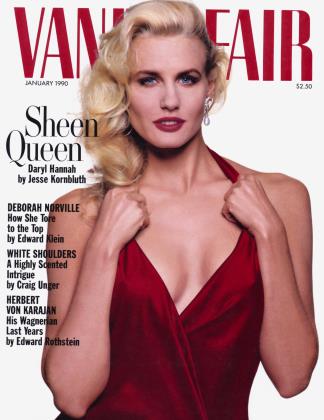

The White Shoulders will contest is finally being settled. The two women who fought over the $125 million fortune of the fragrance's creator, the putative baronWalter Langer von Langendorff, have just received their first bundle of cash. CRAIG UNGER reports on the "Shiny Sheet" worlds of NewYork, Palm Beach, and Monte Carloand on the woman whose milky cleavage turned the old man's head

On a spring afternoon in 1983, Baron Walter Langer von Langendorff and his wife, Gabriele, set out for his midtownManhattan office building, where his employees waited with trepidation. The baron, best known for creating White Shoulders perfume, was concerned that his company, Evyan Perfumes, Inc., continue after his death, and that those closest to him share his wealth. Gabriele, with her imposing Wagnerian carriage and her striking red hair piled high atop her head, seemed to tower over her diminutive, toupeed husband, who, then in his mid-eighties, occasionally appeared sick, weak, and in a childlike daze. Gabriele, in her fifties, had never been active in her husband's business, but she was loathed by his closest colleagues, who thought she wanted her own people running sales divisions and on the board of directors. Gabriele screened the baron's calls and accompanied him everywhere. And now she was coming to take over his company. Leona Robison, Evyan's executive vice president and Gabriele's rival, called two employees to warn them.

"She said, 'I want you to make sure the lawyers are there with you,' '' one of them recalls. " 'I know you're strong. Gabriele is coming to get the stock certificates!' '' Open warfare had broken out over the baron's $125 million fortune.

Today, six years after the baron's death, the battles still go on, but the baron's dream has been destroyed and his pretensions to European aristocracy and international cafe society laid bare. As he neared his end, Dr. Langer, as he was known professionally, was buffeted between Robison and Gabriele, who between them hid stock certificates and used spies, phone taps, and elaborate corporate power plays in their fight for his riches. In his last months, the baron made out three successive wills, shuffling huge chunks of his estate between the two women. The five-year battle over his last will has produced such acrimony that Judge Marie Lambert of New York Surrogate's Court has taken the unusual step of sealing the court records. The parties concerned have agreed not to discuss the case in public, presumably because the charges levied in court are so explosive that neither side wants them aired.

One attorney close to the case likens it to the fight over the estate of the late Johnson & Johnson heir, J. Seward Johnson, who, coincidentally, was a friend of the baron's. In this case, however, the role of Barbara Piasecka Johnson, the Polish maid who married Johnson, is played by two women: there is Gabriele, whose marriage to a rich and older man, many felt, was more mercantile than romantic in nature, and there is Leona Robison, who began as a telephone operator and rose to a position of great wealth and influence. And, of course, there are plenty of highpriced lawyers—from White & Case to Townley & Updike, Shea & Gould, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, and the criminal-law firm of Joseph Marcheso—reaping vast legal fees from the whole affair.

All of which leaves the baron's former employees out in the cold; today the company no longer exists, and its staff lost their jobs. "He was a damn fool for women, and women did him in," says an executive who worked at Evyan for over twenty years. "Gabriele and Mrs. Robison had him coming and going like a yo-yo."

It's midnight at the Cafe Pierre in the Pierre hotel, and the pianist breaks into "As Time Goes By." Gabriele is nowhere in sight. An overdressed blonde stalks the bar in search of someone older and rich. Then she leaves, walking past the stretch limousines on East Sixtyfirst Street and the homeless people lying in nearby doorways, and makes her way to Regine's, two blocks away. There, amid the pink feather boas and mirrored globes, she tries her hand with the Japanese businessmen and African diplomats, aging Eurotrash, and married men out on the prowl. One can smell the scent of cheap perfume.

Ask the bartenders and maitre d's at either place about Gabriele and the baron and you won't get very far. They know who Gabriele is, all right, but she's still one of their best customers, so they won't talk. And as for the baron, he's dead. Besides, his official story is more acceptable—a prim, genteel gothic romance as cloying as the fragrance that made him his fortune. After coming to the United States from Vienna in the late twenties, Langer, a chemist, met Evelyn Diane Westall at a Long Island polo match. According to company P.R., she was called Evyan by her godfather, George Bernard Shaw, and the name stuck. Evyan, also described as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth II, later persuaded Langer to focus his talents as a chemist on the essential oils from which the great perfumes were concocted. At a party in the early forties, the Duke of Marlborough raised his glass to her: "To the whitest shoulders I have ever seen," he said. And so the fragrance that was to become known as the first fine-quality perfume made in the United States was named. It had the good fortune to be launched during World War II, when imports were restricted, making it the only serious perfume for American women to buy. White Shoulders has since lost most of its cachet and today is known largely as "an old ladies' perfume," an image that its new owners, Chesebrough-Pond's Inc., will try to change this spring with a multimillion-dollar ad budget and updated graphics. "The older generation has never let go of it," says a spokesman for Chesebrough, which also markets Elizabeth Taylor's Passion. "They have not advertised to any great extent in over twenty years and it still has enormous appeal. The brand has always stood for romance and there is this incredible, great love story behind it that happens to be true."

Well, maybe not completely true. In fact, the baron's claims to aristocracy were probably as phony as the armorial crest on the brass doors of the company's headquarters on First Avenue and Thirty-fifth Street. According to employees, his real name was Aaron Walter Langer, and, they say, he dropped the first name to conceal his Jewish background. Langer's failed first marriage to an Austrian woman (which produced a daughter) was stricken from his official history, and there is no evidence that Langer's barony was anything more than his own invention. Many think that Lady Evyan's royal ties were also just good public relations. Regardless, the baron and Evyan had enough aplomb and money to get away with it. "There was never any way to back it up, but they lived up to every part of it," says Vivian Bryan, a close friend of the coupie's. "He was a charmer, but he stayed in the background. Evyan was the real dynamo, the grande dame who sat at the head of the table and displayed her jewels." (Among her prizes was a thousand-carat aquamarine said to have once been owned by Sir Francis Drake, one of her putative ancestors.)

The baron was notorious for his behavior with women in elevators.

At the office, the baron was a benevolent dictator of sorts, generous to loyal employees, but tough, stubborn, and so remote that even colleagues who worked with him for decades still referred to him as Dr. Langer. It was an old-fashioned company characterized by European paternalism rather than contemporary advertising or marketing, and it prospered almost in spite of itself. The baron worked in the lab creating new perfumes; Evyan was the financial wizard. Together they made a fortune.

Then, in the fifties,

Evyan suffered a crippling stroke. Langer added a penthouse apartment to their First Avenue office building, which they made their permanent residence so she could work without leaving the building. When Evyan died in 1968, Langer sat by her open coffin and talked to her. He kept her fourth-floor office adjoining his untouched. furnished exactly the way it had been during her life. And at the cemetery near Golden Shadows, the baron's large Westport, Connecticut, estate, he built a pink granite mausoleum, a miniature replica of the estate's Georgian mansion, with the Evyan crest over the von Langendorff name.

In public, the baron kept alive his torch for Miss Evyan until the end. "He had built the company around Evyan, and he was very reluctant to break the image of his marriage to her," says one observer. "That image of purity was inviolate to him." His continuing romance with his late wife may have seemed treacly and sentimental, but it was so potent for him that he often retired to Evyan's office for solace. "Whenever I have a problem, I spend a few moments here," he told a reporter. "It's as close to a visit with this remarkable lady as I can come." Privately, however, the baron fancied himself a ladies' man, and was notorious for his behavior with women in elevators. And then, in the early seventies, he started seeing Gabriele. "With his money, everyone was after him," says a friend. "And Peter [another of the baron's names] fell hook, line, and sinker."

Gabriele Lagerwall was the stuff of tabloid dreams. Not conventionally beautiful, she was dazzling nonetheless, with her Cupid's-bow mouth and makeup and gowns straight out of the Belle Epoque. Even during the miniskirt era, Gabriele's dresses covered everything except her shoulders and her dramatic cleavage. Her hair, as one acquaintance put it, was "so red it hurt your teeth." And then there was her skin, so milk white that she was referred to as the "Milk Maid" or "Snow White." "It was like pure white milk poured from the bottle," says one socialite. "She was so unusuallooking, she would stop you dead in your tracks. By night, it was very effective. But by day, it was scary."

"If ever there was a fantasy in your life, this was it turned to reality," says advertising executive David R. Altman. "The words 'presence' and 'command' were created for her. Gabriele was entitled to any man she wanted, and she never seemed to be attracted to poverty. All myths are inflated, but they always start with basic truths. And these were very large truths."

Yet no one seemed to know her real story. Her nationality was sometimes said to be Dutch, sometimes German. Her jewels were worth millions, but how had she gotten them? And what about Gabriele's supposed first husband, Adahan Lagerwall, who was always conveniently on the other side of the world? Was he, as Time magazine reported, a Swiss oil tycoon with properties in Indonesia? Was he, as another publication reported, a Dutch industrialist? Or was he, as one of Gabriele's friends says, an American sugar magnate with interests in the Philippines?

"I thought she was a drag queen. Her hair was taller than Priscilla Presley's in her wedding picture."

Gabriele has declined interviews for several years, and her past, shrouded in mystery and conflicting tales, is difficult to pin down. Court records show that she was probably bom in the mid1930s, but exactly where is another question. One Evyan executive says she was bom in Hamburg, Germany, but a close friend of Gabriele's, Michael Gordon, says that the baroness is Dutch, and that she and her family moved to neutral Switzerland during the Nazi occupation of Holland. Friends say her wartime childhood was horrifying. "I heard that her brother had been shot in front of her eyes," says an acquaintance who attended parties with her in the sixties.

According to a 1972 book,

The Washington Pay-off, by Robert Winter-Berger, a publicrelations man who worked for Gabriele, she married an American G.I. as a teenager, but left him shortly after moving to the United States. Then, associates say, she took up residence in a hotel off New York's Lexington Avenue. By 1960, Gabriele, reported to be twenty-two but probably several years older, was the talk of the New YorkPalm Beach-Monte Carlo circuit. "Palm Beach may never be the same again after the blitzkrieg of a brand new bush league femme fatale who has upset applecarts all over the Gold Coast this season," Cholly Knickerbocker wrote in 1960, linking Gabriele with an emerald-mine owner and two married men. "Whatever this kid has, it gets them."

"She knew what to do with men like you wouldn't believe," says a regular at El Morocco in the sixties. "I sat and took lessons. A man could be saying the most banal things in the world and her eyes would be glued to him. Her body language was unbelievable. Mme. du Barry would have had to run for the hills.

"For all her money, she didn't know from fine things—except for having jewelry from Harry Winston. Other than that, her taste in furniture was 'early Michigan.' She had plastic flowers everywhere, and when she entertained, it was catered by Child's. She seemed uneducated and unformed, but had a mind like a steel trap. And it was wonderful to see her with a man. Along the way, she perfected her technique, and thought, Well, why let it go to waste?"

In a certain sector of society, Gabriele became known as "one of the world's last great professional beauties," as she is described in Pay-off. According to the Winter-Berger book, Gabriele "was expensive," but a constant parade of rich older men helped her afford her clothes, jewels, a suite at the Pierre hotel, and a Long Island villa. Since many of these trinkets came from their husbands, Pay-off says, women usually hated Gabriele. "All the guys were goo-goo-eyed at those great big tits," says one acquaintance, "and their wives were kicking them under the table."

Nonetheless, Gabriele did her best to win an increasingly visible position in society. Her moment of glory came in 1963, when, after the opening night of the New York Metropolitan Opera, Time magazine gushed, "The eyecatcher of the evening was an auburnhaired stunner with skin like lambent alabaster and a figure like Juno." The $2.5 million worth of jewels she was reported to have worn included 30-carat diamonds on each ear and a 34.8-carat blue diamond ring. Time also reported that Gabriele's companion was her husband, Adahan Lagerwall. But, in fact, there was no such person. Adahan was a name made up by Gabriele's publicist, and Lagerwall was the name of the American G.I. she had married and left. Gabriele's escort was really textile millionaire William Klopman, disguised with a phony mustache and darkened hair because he was still married.

Over the next eleven years, Klopman, the head of Klopman Mills, Inc., which was subsequently taken over by Burlington Industries, was Gabriele's regular companion. A friend of Klopman's says his family was outraged by their relationship, and even today Klopman's son William, the recently retired chairman of Burlington Industries, refuses to acknowledge the relationship. But the older Klopman paid them no heed, escorting Gabriele in New York, Palm Beach, and on the French Riviera. Klopman's greatest gift to Gabriele was a country home in Lloyd Neck, Long Island, about an hour from New York. The area has been home to such disparate people as departmentstore and newspaper scion Marshall Field, the Colgates of the Colgate-Palmolive fortune, and Robin Gibb, but today its larger estates are being broken up, and the odd Kuwaiti has moved in with his helicopter landing pad.

In the early seventies, Gabriele's house added to her myth. The fortresslike edifice—designed by Edward Durell Stone on twenty-two acres facing Long Island Sound—had magic buttons, Gabriele told Time, so she could seal off both wings for nude swimming in the indoor pool in its central courtyard. Some guests recall evenings there as formal sit-down dinners with strolling violinists, but rumors of wilder affairs persisted. One guest recalls a dinner at which all the gates came crashing down, presumably "to keep the help confined while the guests reveled." Another recalls Klopman tumbling off a perch from which he was spying through a peephole. It was said that Gabriele never slept there, that she was always chauffeured back to New York after using it for entertaining. One paper reported that at one time Gabriele's will had a proviso that the house be blown up after her death.

When Klopman died in 1974, one secret surfaced about his relationship with Gabriele that no one had guessed: they had married. One reason for the intrigue may have been that even though Gabriele cared deeply for Klopman—anyone who knew her said that—wherever she went she was surrounded by other men. "She always had something going on the side, and Klopman put up with it," says one partygoer. "It was like a public humiliation. There was always more than one." Among them was Baron von Langendorff.

In the early seventies, he had started making the rounds of Cannes, Monte Carlo, and Palm Beach with both Gabriele and Klopman. "He went after her like a steamroller," says a friend of Gabriele's. "And if someone so much as touched her hand, his toupee would shake with anger. ' '

The baron and Gabriele were an unlikely couple. She was only two or three inches taller than he, but over the years had put on considerable weight, and with her imposing girth and manner, she seemed a good head taller. "That little squirt just could not take his eyes off her," says a friend. "When she danced around the comer, he'd stand up until he could see her. And when they stood side by side, he seemed just as tall as her bosoms."

The Old Guard was scandalized, and everywhere they went Gabriele was shunned. "The baron used to go to Palm Beach with Miss Evyan and she was marvelous and so right," says a friend of Langer's. "Then he turned up with Gabriele. These wonderful Palm Beach women were so distressed with her behavior that they wouldn't have any of it." Gabriele still patronized the big charity balls, but when it came to seating, sources say, she was consigned to Siberia. "I was told, 'If you value your reputation you won't be seen with her,' " says one socialite.

Publicly, the baron continued to pay homage to Evyan. In 1979, Langer paid $1.5 million for the thirty-seven-room Gramercy Park town house of the late Benjamin Sonnenberg, and christened it Evyan House. He made it into a corporate temple of sorts to his late wife, filling it with portraits of women displaying the "white shoulders" decolletage. In addition, Langer collected miniature replicas of the inaugural gowns of all the First Ladies, intending to exhibit them in Evyan House.

Continued on page 146

Continued from page 93

But secretly, probably in 1976, he married Gabriele. The relationship seemed to follow the same pattern as her marriage to Klopman. According to Evyan sources, Gabriele still lived in her suite at the Pierre, and maintained another suite there as well, presumably to entertain guests. And she was still known there as "Mrs. Lagerwall" (even the baron sometimes introduced her by that name).

Of course, the baron wasn't everything he pretended to be, either, and if Gabriele was a social embarrassment, he didn't mind. When Frank Sinatra and his wife took a table near the baron and Gabriele at La Grenouille one evening, Gabriele's efforts to catch Sinatra's eye were so obvious that the maitre d' asked her to change seats. "She didn't bat an eye and got up and left," says an observer. "And the baron was so taken by her he didn't complain."

And what was so wrong with their relationship, after all? When he was sick, Gabriele took care of him, and when he was well, he had fun. Gabriele even had a sense of humor about the objects of her affections. "She told me she specialized in geriatrics," recalls one friend of Langer's. "She said, 'I make them happy, and I do much better than the doctors.' " Scores of snobbish Palm Beach matrons had taken similar paths up the social ladder, so it was not surprising they scorned her. ' 'Because of her decolletage and her jewels, because she is a nonconformist in her dress and bearing, society misunderstands her," says Gabriele's friend Stella Sichel, a Manhattan real-estate broker. "She is extremely generous, whether it is taking friends to La Grenouille or to Monte Carlo. She surrounds herself with mystery. Even when she has been married, she didn't tell her close friends. But she is still one of the most loyal, loving women I have ever met."

Michael Gordon, who became close with Gabriele in the early seventies, says the Winter-Berger book and reports from partygoers give a misleading picture of Gabriele. "You read the wrong book," he says. "And Time magazine just made a mistake that was completely irrelevant. Who tells you such lies about her? Gabriele is a very sensitive, secretive person with a heart of gold. She has a Jekyll-andHyde personality. She can get nasty, but she is really very shy, and very goodhearted. She is not good with employees when she is mad. But when her anger leaves, she is a pussycat. If you are her friend, the only thing you can think is that she is so attentive that you will never get so much attention.

"But very few people know what she is really doing. All the girls feel inferior to her. They are just jealous and they gossip. People go to her parties and, because she lives in a style like Buckingham Palace, they gossip. You know what ugly statements I have heard? Well, I tell you she had more money than Peter when she married him. To go out with more than one man, that was just her style."

Besides, whatever one thought of Gabriele, she was the baron's wife. That meant something. Under New York State law, it meant Gabriele was entitled to at least one-third of her husband's estate. If she was truly the gold digger many thought she was, the real measure of her success would be how she fared in the baron's will.

Langer had always kept his distance from his employees, and as he entered his eighties it became clear the only person he had ever considered as his successor was a blonde in her fifties named Leona Robison. A native New Yorker who lives near Gramercy Park, Robison, according to a company source, grew up in the area in which she now lives. But an attorney for the baroness says she grew up in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn.

In any case, Robison started at the company in the fifties as a telephone operator, but gained Langer's trust and confidence increasingly after Evyan's death and by 1976 had been promoted to executive vice president.

Robison—married three times, most recently to a naval officer who is now deceased, according to a friend—is taciturn in describing her relationship with the baron. "I knew him for twenty-five years, and I worked with him every day," she said, "but I never saw him out of the office. I did not socialize with him."

But they apparently did have a special relationship. "I really don't think they were lovers," says one employee. "But she had a very strong hold over him. When they had fights, she would go off for a week and pout. Then he would send flowers, and she would come back and get a raise."

In any case, in his 1971 will, Langer left Robison most of his huge estate, saying she "filled the role of daughter to me at times when life was not easy." Even in 1980, several years after Langer had married Gabriele, Robison was still his single biggest beneficiary. And she received other substantial benefits as well: Langer hired her daughter and put both women on the Evyan board of directors; according to one Evyan employee, in the late seventies he sold her a house in Westport for the nominal price of $150,000, and later offered her a generous deal for Golden Shadows. Then, in 1982, Langer gave Robison a gift said to be worth millions of dollars: the rights to the formulas for a number of Evyan perfumes.

Robison interceded for employees in personnel disputes so enthusiastically that they called her "Lee Bountiful," but few were impressed with her business acumen. "She was a mother figure," says one. "She was terrific if your cat had kittens. But if you needed to talk business, she wasn't a real businesswoman." Langer may have shared those sentiments, but one employee recalls his saying that "if anything happened to me, I know she would take care of my people the same way I would."

"If I die," he told another staffer, "I want the company to go on. She is weak. But she will run the company."

The baron was weak as well. Those who saw him during this period are of two minds as to his health. Increasingly frail, sources say, he had had pneumonia, a mild case of diabetes, and sometimes appeared to be in a drugged stupor. Gabriele insisted that he constantly be in the company of a nurse. "What Gabriele did for that man!" says Michael Gordon. "She was bringing in the best doctors constantly. They were doing extraordinary things." But friends of Robison's remember the baron as being as lively and alert as anyone in his mid-eighties can be. "He was fine," says one. "Gabriele just wanted it to appear that he was ill so she could increase her control of him."

Ultimately, the baron's problem was one that no doctor could cure—Gabriele and Leona were at war over him. To those in the baroness's camp, Gabriele was simply trying to protect her aging husband and look after her own interests. "She is not capable of measuring up against the tricks of someone like Robison," says Michael Gordon. But Robison's allies saw Gabriele as a shrewd and worthy adversary. "My first reaction on seeing her was her overwhelming power," says Maij Basili, a friend of the baron's in Westport. "Lee is no match for her [Gabriele]. She's just a Girl Scout."

The warring parties agree only that the two women detest each other. "They are deadly enemies," says Gordon. "It is not hate. It is hate with a passion."

In early 1983, the machinations began in earnest, with the battles taking place mostly in the pink brick Evyan Perfume building on First Avenue. One of the first salvos was fired in March, when Langer and Gabriele came to the office with Joseph Blasko, a Canadian entrepreneur. "Gabriele told me that Blasko would be a new member of the Evyan board, and that Dr. Langer would no longer be coming in every day," says a former executive at the company. Instead, it was explained, the baron would send a list of written instructions with Blasko, who would need a desk and a telephone.

According to the executive, Robison was shaken. The baron had always delegated authority to her. Robison went into Langer's office to discuss it privately with him. He was disoriented. When she emerged, she held her head in her hands and cried.

"He doesn't even know who I am," she told another executive.

Later that afternoon, Langer appeared to have come out of his trance. He went into Robison's office and embraced her. He had changed his mind. Blasko would not go on the board. "Don't worry," he said. "What can be done can be undone."

From the beginning, longtime Evyan employees saw such interventions as an attempt by Gabriele and her allies to take over the company and sell it, which would ultimately cost them their jobs. That was not far from the truth. But the baroness's friends saw it simply as Gabriele's effort to protect her interests and tell an old man it was time to retire.

"It was all Peter's fault," says Michael Gordon. The president of Koret Handbags, Gordon is a self-made multimillionaire who came to this country from Hungary after the war with $175 to his name. He is seated in his Madison Avenue office, surrounded by Christian Dior and Givenchy leather goods. "Peter was a maniac. For him, Gabriele was untouchable, a glorious, beautiful woman. He adored her. He kept her away from his business activities. He said a baroness must never intervene; she must be aloof. She must be above those little employees. And so everybody was jealous of her. She had nobody at the company. They hated her. They were rotten to the core. They had nothing and they wanted to get everything.

"Ten times I said, 'Peter, stop it!' " recalls Gordon. " 'You are old enough, you have enough money. Sell the company.' Each time, he got red and never would do it. That company was his dream. So long as Peter felt like a young man, nobody could change his mind. But when he was not feeling good, then Peter was willing to listen. I found a very good man for them, and I suggested he run the company as a managing director. But Robison torpedoed it, and the whole reason was it came through Gabriele."

Meanwhile, the company had already taken on one of Gabriele's friends, a tall, dark Arab businessman in his mid-forties named Abdul Rahan Soria. A year earlier, Soria, Gabriele, and another Arab businessman had returned to the Pierre after drinks at Regine's when two men handcuffed them and robbed Gabriele of more than $1 million in jewels. Soria lost $20,000 in cash. No arrests were ever made. It was the second time Gabriele had been the victim of a major jewel robbery, and it left several unanswered questions: Why did Soria have so much cash on hand? Why did Soria tell police he was from Syria, as reported in The New York Times, when he had registered at the hotel as a Kuwaiti?

In any case, Soria's job was to head Evyan's Middle East sales, which until then had been negligible. He soon put together three deals for a total of $8 million worth of perfume, a huge amount for the small company. Employees were ecstatic, as was the baron, who began talking about a new Evyan branch in Abu Dhabi. The only problem was the perfume's destination—Beirut. "Who were they kidding?" says one executive. "There was a war there. That shipment was never going to Beirut."

A key factor in Evyan's long-term prosperity had been its success in confining distribution to select retail outlets. In this case, however, the Middle East shipments never left the country. Instead, investigators later discovered, they were packed into containers with phony bills of lading and secretly diverted to unauthorized outlets throughout the United States, surfacing mostly in the West in retail stores that were not nearly as exclusive as those that normally sold the perfume.

"Diversion is not always illegal," says one former company manager. "But it's an internal disease, and it can kill you." Yet, according to an Evyan executive, Soria took in more than $600,000 in commissions for his "Middle East" deals, at a rate more than double that of other sales representatives.

Gabriele's allies assert that Soria was a friend not just of hers but of Peter's as well, and that ultimately the baron was responsible for all hirings. Moreover, one of Gabriele's lawyers argues that the diversion was a setup—a "sting operation" of sorts—to make Soria and Gabriele look bad. Former Evyan employees deny those charges, however. They feel certain that the baron had hired Soria at Gabriele's urging.

Meanwhile, although Gabriele was not terribly visible to employees, her influence was clearly growing. The baron had moved from his penthouse apartment in the First Avenue office building to the Pierre a year or two earlier. He lived in a separate suite from Gabriele, but all calls were funneled through her. The baron still went to Westport for the weekends without Gabriele, but even there, a friend of his says, she had him followed. By 1983 he rarely came to the office. When he did, he was usually accompanied by a nurse, and occasionally by Gabriele. In the latter case, according to one employee, Robison would scurry away to the lab or leave the building just to avoid her nemesis.

At this point, an executive says, Robison had access to Dr. Langer only when Gabriele went out late at night or when they talked during secret phone calls at one or two in the morning. Petrified of Gabriele, Lee consolidated her resources. Evyan sources say a nurse in the company clinic, a secretary, a lab assistant, a chauffeur, executives, and a private investigator all reported to her any developments about Gabriele and Soria.

During his Westport weekends in 1983, the baron began meeting regularly with Marj Basili. But apparently there were people watching him. "One time, Peter came out of the house and the rhododendron bushes began moving," Basili says. "I told him people were hiding behind them, and he said they were just the gardeners. He tried to laugh it off. But they got in a car and followed us, even when I turned down a dead-end street."

"To say they were spies is bullshit," says Michael Gordon. "Of course Gabriele wanted to get information. She would have done anything to get that woman [Robison], who controlled everything that belonged to her. But spies? It was very legal for her to look out for her own interests."

In any case, the baron didn't seem to mind. "At first he thought it was fun, all these people fussing over him, like hideand-go-seek," says Basili. "Whenever he left his property on foot, he'd sneak out through holes in the fence. He enjoyed making them crazy trying to find him. Once, he told me to meet him at a gas station in an hour, and I waited and waited." Basili was about to leave when Langer finally showed up.

"Damn it," he said. "They mended the fence."

At times, though, Langer seemed to realize the seriousness of his dilemma. "I'm very distressed," he confided to Basili in March. "I've just found out that my wife has been trying to take over my company."

"But whenever he returned to Gabriele, poor Peter was overwhelmed," says Basili. "He was an exhausted old man, and she is very hypnotic and powerful."

On April 26, 1983, the baron signed a new will, giving Gabriele more money. Three weeks later, on May 12, he wrote still another will, making Gabriele the chief beneficiary for the first time. Robison would get only $6 million, and almost all the rest of the estate, nearly $120 million, would go to Gabriele.

News about each development trickled down through the Evyan hierarchy. The employees watched the psychodrama unfold, knowing their jobs hung in the balance. "We knew what we had with Lee," says one. "We had no idea what Gabriele's intentions were. To align ourselves with Gabriele would have been suicidal."

Robison put a brave face on the situation. One executive recalls, "She said, 'If giving more to Gabriele will prolong his life, that's all I want.' " But, in fact, nothing was going right for her. Presumably for legal reasons, it was determined that the transfer of one of the baron's valuable Westport properties to Robison had to be nullified. According to an employee, a few days after the May will, the baron went to Robison's office to undo the initial transaction. "Lee took a check and property transfer and waved it in his face. 'Here's your property back,' she said.

"The old man just sat there and cried like a baby," says the employee. "He'd been like a king. But now he didn't have the strength to fight back."

For Gabriele, the May 12 will posed only one problem: it specified that Evyan could not be sold without Robison's consent, thereby binding her to her rival indefinitely. But later that spring, even that dilemma was apparently resolved. The baron gave Gabriele stock powers for all of his holdings—not just the fragrance company, but all the properties in his estate. Once she had the actual stock certificates in hand, Gabriele would own everything.

There was just one catch. The baron had the stocks put in a safe in a fourthfloor storage room of the Evyan Perfume building. To get the certificates, Gabriele had to go through Leona Robison and two controllers who were company loyalists. The showdown came in late May or June, when the baron called Robison, saying he and Gabriele were coming to the office for the stocks. But unbeknownst to Gabriele, the baron had apparently tipped off Robison so she could get to the certificates first.

The battle took place in the baron's fourth-floor office, a Hollywood version of a baronial executive suite, full of expensive reproductions rather than real antiques. To the left of Langer's desk was Evyan's office, with fresh flowers, its door open, as if she might walk in at any moment.

The baron and Gabriele got there midafternoon, accompanied by her lawyer. Robison was not there, but the two employees briefed by her entered the baron's office with an attorney representing the company.

Gabriele sized up the situation immediately. "Get out!" she exploded. "Nobody invited you!"

One of the employees looked at Langer as if to say he—not Gabriele—was the boss. But Langer ignored the squabble. "Gabriele was very careful," says the employee. "She never indicated she was trying to take the company away from Dr. Langer. She never asked for the stocks in my presence. He did. But anything he said, we believed was at her instigation."

Finally, the baron asked for the stock certificates.

"I only have copies," he was told by the controller.

"Gabriele had a fit," says one of the employees. "Then her mood changed completely. As soon as she saw she wasn't winning, she went from being very nasty to having a normal conversation."

Finally, Gabriele and Langer left without the certificates. The will was still very much in her favor. And the war wasn't over yet.

In June, the baron and Gabriele attended a company picnic in St. Vartan's Park, across the street from the Evyan building. It was a hot day, but Gabriele wore a fur jacket and danced with an Evyan executive. "Suddenly she said, 'I have to go,' " her dance partner recalls. "She sat down with Dr. Langer and took a cup of soda and started dunking a cookie in it and feeding him. [The baron's health was a continuing source of controversy, with different factions battling for control of his care—and of him. There were constant fights between Gabriele and one of the nurses.] The nurse said, 'What the hell is she doing? He's a diabetic, and she is dunking cookies in Coke!' Then she ran over and took it out of his hand."

The one hole in Gabriele's security net remained Westport. She was not unaware of it, but she could not entirely stop the baron from seeing Maij Basili. Because Basili was not a beneficiary in his will or on his payroll, Evyan employees saw her strategic importance and moved in. "They told me I could say things to him that Lee couldn't because he would immediately take the side of his wife," Basili recalls.

On a Saturday early that summer, the baron and Basili went for a drive along the Westport town beach. For all of his purported medical problems, the old man was regularly dragged out by Gabriele to La Grenouille and Regine's, he told Basili, where they would stay until four A.M. "Gabriele made his life miserable," says Basili. "She was crucifying him. He was often in tears, frail, and completely dependent. When I realized this very nice gentleman was under house arrest and didn't know it, I felt it was my duty to let him know. He was so distressed and wanted a divorce. He just couldn't fight this woman. He was so heartbroken. He felt betrayed that Gabriele was about to undo the company, devastated. He said, 'My dear, I can't even think about it.' " Afterward, Basili brought the baron back to her house. Not long after their arrival, the phone rang. It was Gabriele. "She insisted that he go home immediately, that he wasn't feeling well," says Basili. "She must have had us followed."

When it came time for their summer trip to Monte Carlo, Gabriele went alone. For the first time in months, Robison had the baron to herself. Soria was her major concern, and not just because of the diverted Middle East sales; Gabriele had been spending a lot of time with him. "Dr. Langer knows exactly what's going on," Robison told a colleague. "But he can't do anything about it. He's afraid of Gabriele. He knows she's fooling around with Soria. He won't divorce her. He won't leave her."

But on July 22, with Gabriele still in Europe, the baron finally decided to act. "He knew exactly what he wanted," says one executive. "Dr. Langer had come to his senses."

By coincidence, one of the shipments that was supposed to go to the Middle East was being sent out that day. That meant Soria's associates would be around, and Langer wanted to avoid them. He secretly met with his lawyers in an adjacent building. Once again, he signed his last will and testament. Instead of getting $120 million, Gabriele would now get only $100,000 in cash, plus $1 million a year from a trust set up by the will. And Robison would get nearly half of the entire estate—about $60 million before taxes. In addition, Langer left several million dollars to employees of the company who had been there for more than ten years. Gabriele, unaware of the change, returned from Europe at the end of the summer.

On the second weekend in September, Dr. Langer went up to Westport, and again saw Marj Basili. She gave him a tour of some local real estate, including an abandoned embalming plant which he was considering buying as a new home office for his company. He told Basili that he would call her on Wednesday to let her know if he was interested. Her son Sep, a college student, took the baron to get a haircut. "He was in truly good health," says Sep. "It was clear he had a handle on what was going on in his life."

On Monday and Tuesday, back in New York, the baron wasn't feeling well and didn't go into the office. On Wednesday, September 14, Basili was expecting him to phone. "I thought it was strange that he didn't call me," she says.

That morning, Gabriele called an Evyan executive and had him seal off the penthouse apartment in the Evyan office building. As soon as he got the order, he realized the baron was dead. Michael Gordon, who was in Hong Kong at the time, also received a call from Gabriele. "She was out of her mind,'' he recalls, "crying for twenty minutes, saying, 'Peter died, Peter died.' "

According to the New York City Medical Examiner's Office, Baron von Langendorff died of "natural causes." He was not hospitalized, nor was his regular personal physician called. There was no autopsy, nor was there any evidence of foul play—just plenty of wild accusations and unanswered questions.

"If you want my opinion," says one executive, "he finally said, 'To hell with both of you. I'm just going to die and let you tear your hair out.' "

A week later, Gordon says, when Gabriele found out about the July 22 will, "the shit hit the fan. She absolutely could not believe it. She said, 'Peter would never do that to me.' She told me that a hundred times. She felt the biggest injustice in the world had happened to her and she had to fight it." Not long afterward, Gabriele called Marj Basili and asked her to come to the Pierre hotel. They met downstairs in the cafe after Gabriele made Basili, accompanied by her son, wait for about an hour. "I thought she was a drag queen," says Sep. "She was out of control, wearing a phenomenally low-cut, red polka-dot dress. Her hair was taller than Priscilla Presley's in her wedding picture. She was incredibly garish."

Gabriele was accompanied by Soria, tall and lean, dressed in a gray suit. The baroness introduced him as her bodyguard, saying she needed protection against kidnappers. But Soria held her hand throughout most of the meeting.

According to Basili, Gabriele seemed alternately to want to befriend her and to threaten her. "She told me before the baron died he left something for me," Basili recalls. As she spoke, Gabriele held a large manila envelope tantalizingly out of reach.

"She told me that she had every conversation with him taped," says Basili. "I was shocked, but I laughed." Gabriele then asked if Basili wanted anything from his estate in Westport.

"I said I would love to have his monocle, as a keepsake," Basili recalls. "She was trying to entice me. She kept saying, 'Wouldn't you like jewelry or furnishings? Isn't there anything in the house that you would want?' "

Gabriele then tried to elicit information about Basili's conversations with the baron prior to the July 22 will. But in the end it was a standoff. Gabriele never turned over the envelope to Basili, nor did Basili proffer any information. "I didn't want anything from these people," says Basili. "I realized how terrible she was to him. The only reason I went was curiosity."

It is six years since the baron's death, and his estate has still not been fully distributed. A settlement has been reached after a five-year court battle, but ancillary litigation continues. Gabriele is not the only principal in the case who is hard to pin down. Leona Robison declined to return phone calls after two brief interviews in which she had said, somewhat disingenuously, that the reason for the delay in distributing the will is that "judges are busy. The judicial system is backed up like crazy. It always happens." And she denied that there was ever any dispute whatsoever over the baron's estate. "Whether you believe me or not is your business," Robison said. "It doesn't matter to me if my employees like to feel important. I say they're lying. You can believe them or you can believe me."

It is not surprising that Robison is bitter about what happened. Although she will inherit a considerable fortune, the company she wanted so much to run no longer exists. "Lee doesn't know about money," says Marj Basili. "She is simple. She might be dripping in mink and chauffeured limousines, but she'll still drop by the PX in Brooklyn to see if there are any bargains."

Initially, employees were pleased that Robison succeeded the baron as company president, but the business remained as chaotic as it had been during the last year of Langer's life. The litigation over Langer's estate dragged on year after year, which left the company's future in doubt. If it was sold, everyone's job would be on the line. "Lee told us as soon as they settled and got Gabriele out of the way, we could continue," says Barbara Swanson, an employee of more than twenty years. "She said she wasn't going to sell."

Still, many employees left work early or came in late. Robison herself rarely came in before noon. The Evyan board of directors—which consisted of Robison, her daughter, and a company lawyer— voted her a raise to $500,000 a year. She made her daughter executive vice president, and doubled her salary to nearly $100,000. An F.B.I. investigation led to the conviction of one of the controllers for bank fraud. Robison began to get anonymous letters from employees. "This place is run like a circus," one read. "Who is selling the popcorn, cotton candy, and peanuts?"

Finally, in late 1987, Robison's lawyers told her they thought she had won the case. But in January 1988, Gabriele sued Robison and her attorney John Paul Reiner for more than $20 million, charging fraud in withholding the baron's stock certificates. "Dr. Langer had made a gift of the stock to his wife," says Gabriele's lawyer Joseph Marcheso. "If Robison hadn't wrongfully held the stock back, it would have been a complete transaction. Whoever owned the stock would have owned the company."

"It scared the hell out of Lee," says an Evyan executive. "Suddenly, she saw she could lose everything."

Robison capitulated immediately. The following month, both parties agreed to a compromise. This time, it was a draw. Robison and Gabriele would each get $25 million to $30 million, with $5 million going to charity, $3.5 million to long-term employees, and the rest to taxes.

Judge Lambert's settlement of the will may have been agreeable to the two women who fought over the baron, but it left the estate divided in such a way that to pay the taxes the company had to be sold. In the fall of 1988, fourteen companies bid for Evyan, and in February 1989 it was sold to Chesebrough-Pond's Inc., a division of the Dutch conglomerate Unilever, for $75 million. Virtually every employee—250 people, some of whom had been there for more than forty years— lost his job.

Many expressed feelings of shock and betrayal, especially toward Robison. More than eighty employees claim that in February 1988 she asked them to refrain from accepting any raises to make the business more salable, and that in return they would all get one year's severance pay. But upon the sale of the company, employees received only five weeks' severance, and they are suing as a result. Robison has denied any such promises were made, and the suit is currently in discovery. A source close to the case says that Gabriele and Robison have already been paid $3 million each from the sale of the company. At the same time, according to Anthony Dilimetin, an attorney representing the employees of the company, "the sixty-eight employees who were to receive $50,000 each for being employed in excess of ten consecutive years have so far been denied their payment for no legal reason whatsoever."

Meanwhile, the Evyan building on First Avenue has been sold. Its display windows are bare, and its doors are locked. Evyan House, the magnificent town house on Gramercy Park, is empty except for the people taking care of it, open only to prospective buyers. White Shoulders perfume will continue to be sold, but by a conglomerate, much against the baron's wishes. He may have been an ersatz aristocrat, yet the company he created was profitable until the end. There was no real reason for it to close. But somewhere in his last years it was destroyed by the greed of the two women he cared about most. ''So many things were lost as a result of these two women fighting over this poor man," says one executive. Of course, that leaves Gabriele Lagerwall Klopman Langer von Langendorff, a woman who seems to use her married names only when her late husbands' estates are in litigation. ''People always misunderstand her," says her friend Stella Sichel. "She is extremely private, and she doesn't let people see her. She may be painted even when she is mourning inside."

It is hard to know how true that is, because the baroness, who initially agreed to an interview, canceled her appointments with me and did not return my subsequent phone calls. Over the ensuing three months, I negotiated with attorneys from three separate firms—all representing the baroness—for an interview. Talks with Arthur Brown of Parker, Duryee, Rosoff & Haft ended with his not returning calls. Joseph Marcheso threatened to sue Vanity Fair. Discussions with Sanford Schlesinger of Shea & Gould led to an agreement to a written—not oral—interview. But later Schlesinger called and said, "I can't find the baroness. I've left messages for her at many places and I don't know where in the world she is."

Wherever she was, Gabriele eventually returned to New York. She is still living in the Pierre hotel, awaiting distribution of the rest of her share of the estate. And she is not alone. Now that the baron is dead, one of her close friends has moved into the Pierre as well—Abdul Rahan Soria.

"He is a very nice man, a very kind man," says a friend of Gabriele's in Cannes. "And I think she loves him very much."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now