Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

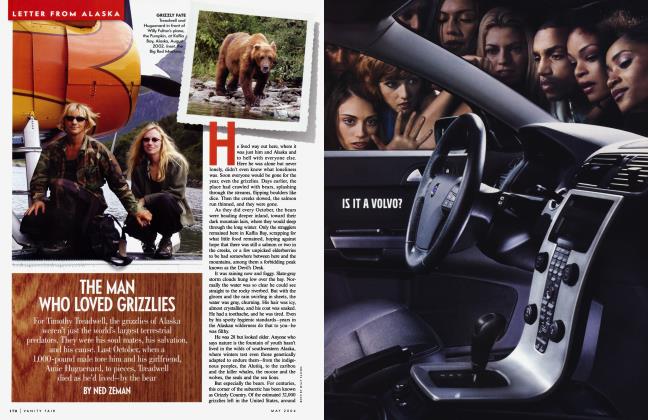

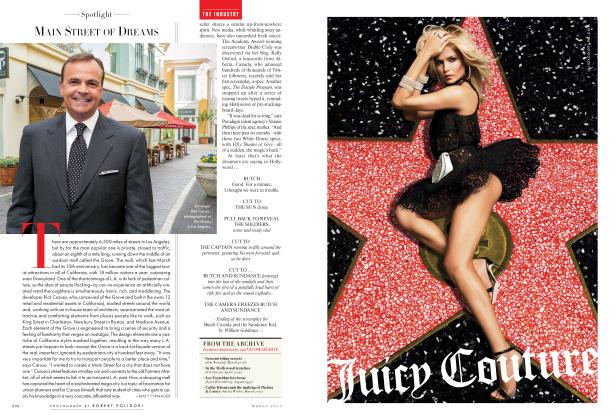

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHotelier André Balazs, whose first development project in Miami was in 1997, is back on South Beach. His revival of the old Raleigh Hotel has emphasized its original jet-set Latin glamour. But a more radical renovation of the "old lady" Lido Spa—opening in September as the Miami standard—turns the local aesthetic on its head. Matt Tyrnauer frames Balazs's double take.

May 2004 Matt Tyrnauer Robert PolidoriHotelier André Balazs, whose first development project in Miami was in 1997, is back on South Beach. His revival of the old Raleigh Hotel has emphasized its original jet-set Latin glamour. But a more radical renovation of the "old lady" Lido Spa—opening in September as the Miami standard—turns the local aesthetic on its head. Matt Tyrnauer frames Balazs's double take.

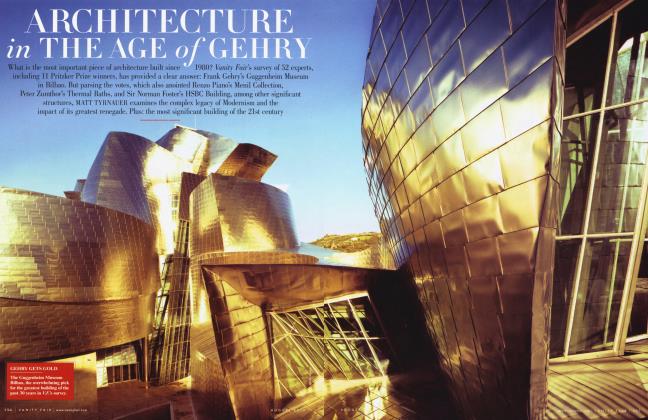

May 2004 Matt Tyrnauer Robert PolidoriIn 1991, a decade after Miami Beach's Art Deco district was given historic architectural status and saved from obliteration, the Raleigh Hotel, on Collins Avenue at 18th Street, was lovingly restored, and what had been a fine example of the work of Lawrence Murray Dixon, the architect who embodied the early Art Moderne-Miami style, was brought back to life. It was among the first of the larger neglected, decaying buildings from the pre-World War II glory days to be spiffed up. An elegant mini-skyscraper on the beach, the Raleigh helped set the tone for the resort city's big comeback, one of the happiest stories of architectural conservation in modem times. By the late 90s, however, the hotel, which is known for its curvaceous, Busby Berkeley-esque swimming pool, had begun to lose its new luster. Flashier renovations, representing evolutionary leaps in the South Beach Renaissance—most notably the Delano, the surrealistic pleasure dome designed by Philippe Starck, just a few doors down from the Raleigh—sucked away all the oxygen and many of the clients.

But this season, under the direction of a new owner, André Balazs, the Raleigh appears to be entering another boom period. Balazs, 47, has an impressive track record of renovating hotels and at the same time reviving architecturally significant structures. The Chateau Marmont in Hollywood, the Mercer in New York's SoHo, and the Standard in downtown L.A. are three prime examples of his efforts. Now the Raleigh, built in 1940, can be added to the list, as well as another hotel 15 blocks away, the Lido Spa (1953), which he is also renovating. Balazs plans to relaunch the Lido—a down-at-the-heels specimen of the postwar MiMo (Miami Modern) style—in September as the third in his chain of minimum-cool, reasonably priced Standard hotels. (The second is also in L.A., on the Sunset Strip in West Hollywood.) The Miami Standard will have a large Eastern European-style bathhouse as its centerpiece, with an emphasis on therapeutic mud—different from the other two Standards, which have an emphasis on pounding music, poolside cruising, and late-night vodka-and-Red Bull consumption. (Balazs's hotel empire also includes the Sunset Beach on Shelter Island, New York.)

Sipping Domaine Ott in a grove of seagrape and palm trees in the newly landscaped backyard of the Raleigh, Balazs talks about what he sees as "an excavation of the old Miami." He tells me, "This is really the last wave, because this hotel and the Lido Spa are the last two places to go." Spread before him on a red lacquer-topped table (inspired by one he admired at a beach club in Saint-Tropez) are archival images of the Raleigh, a 1947 edition of Life magazine featuring Miami, and a book on Lawrence Murray Dixon's buildings. (Dixon worked for the New York firm that designed the Waldorf-Astoria in Manhattan, and he was a key inventor of the modemDeco fusion in Miami Beach. He died at 48, after having built 16 hotels along the beach, including the Tides.)

Taking inspiration from the vintage pictures, Balazs and his small design staff are attempting to restore the old spirit of the hotel, which was one of Dixon's most elegant. "Not a literal restoration," Balazs says, "but an homage to a long-lost, but better, past. The people who built Miami, their vision was a look toward the glamour of the French and Italian Riviera. What people have done since—the pastels and so on that were used in the 80s—has been endlessly copied and become a cliche. So we went back, looked at the original photographs from the 40s, and saw a braver and more original vision, a bolder, very sexy look." One bird's-eye-view photo of the pool shows black-and-white checked umbrellas with fringe, which Balazs has re-created. Hand-colored photos from the period show strong oranges, hot pinks, and ketchup reds, and those colors have been applied to some of the exterior walls near the long row of white cabanas, just behind the pool.

"It's not a literal restoration, but an homage to a long-lost, but better, past," Balazs says.

The Miami Vice palette has been banished, except for a Creamsicle orange used on the logo and in the interior of the dresser drawers in the rooms, which, Balazs says, are his fantasy of what "a glamorous hotel in Cuba might have been like." The original brown-and-ocher terrazzo floors, with an inlaid pattern that repeats the outline of the pool, have been preserved. Black lacquered Deco furniture is coupled with wicker and rattan. There is grass cloth on the walls. "We were thinking of the time when Porfirio Rubirosa was a star of the international jet set, and you could find places in Latin America where you might be dressed in a white tie one minute and the next minute in casual clothes.

"This hotel has had three lives," Balazs continues. "Life magazine singled it out as one of the most beautiful pools in Florida in the 1940s. That disappeared in 20 years, like all of Miami did. Then this guy, Ken Zarrilli, a real-estate developer from New York, who has a great eye, made the Raleigh the place to be in the early 90s. It was the vanguard—six or seven years before the Delano. And now I want to make it the sexiest, most sophisticated hotel on the beach, similar to the Chateau Marmont and the Mercer."

Since buying the Chateau Marmont, in 1991, and successfully bringing it back to life, Balazs has acquired considerable expertise in the delicate, intuitive art of creating a proper hotel mood, through lighting, music, staffing, and a thousand minor aspects which come together to make a powerful whole. Some of the tricks are simple; for example, a bunch of $ 10.99 tiki torches and a few strings of French festoon lights make the palm-and-sea-grape grove of the Raleigh look enchanted at night. A landscaper suggested that the trees be planted symmetrically, but at the last minute Balazs scrapped the plan and had them set out in a random pattern. A teak deck was in the way, but free-form holes were cut into it so that the trees could poke through. Balazs's employees are rarely from the "My pleasure to serve you ... Certainly, right away" school. Early on, while staffing the Chateau Marmont, he realized that an actor/model can lend a certain charm to room service or a package delivery. (As a side effect, you may end up with Baz Luhrmann's or Christopher Walken's faxes, but then, they may end up with yours, and that is part of the fun.) The "cultural attaché" at the Raleigh, Manije Mir, was once an assistant to Farah Diba, the Empress of Iran. "At the Raleigh, there are a lot of wholesale changes—everything from Eric Ripert, the chef at Le Bernardin in New York, being brought on to supervise in the kitchen to the replacement of almost every piece of furniture—but I think the goal is for someone to come in and say, 'Oh, my God, it's so perfect! Nothing has changed!'" says Balazs.

Sandra Kahn, from Highland Park, Illinois, approaches Balazs while we are talking, and tells him that she has been staying at the hotel on and off since 1942. "I know who you are, and I want to thank you for bringing this hotel back to the way the old Miami Beach was. u didn't miss a trick," she says. Kahn's sister Norine Siegel adds, "We used to stay here when it was the kosher Raleigh! I bet you didn't know it was a kosher hotel, or that Al Capone's men used to stay here. Martha Raye, the Big Mouth, had her club right across the street." There was, for a time, a synagogue on the premises, according to an old brochure. The cabinet containing the Torah was in what is now the oak-paneled cocktail lounge at the back of the lobby, which originally had a painting of Sir Walter Raleigh and Elizabeth I over the fireplace. Balazs is not planning to reintroduce the Torah, but he has commissioned a portrait to replace the painting, and the Sir Walter theme will be played up. A stag symbol, part of the Raleigh-family escutcheon, has been adopted for the hotel logo and emblazoned on the matchbooks and stationery, and it will soon confront guests when they lift up their toilet-seat lids.

With the Lido Spa, which is located on Belle Isle, along the Venetian Causeway, Balazs faced a far greater renovation task. Built as a motor hotel, it was renovated in 1963, and features a facade designed by Morris Lapidus, master builder of the Fabulous 50s-style modernism that reached its height with Lapidus's Fontainebleau and Eden Roc hotels. (Lapidus lived out his last years in an apartment building of his own design, across the street from the Lido.) The Lido's wide, low-slung fagade has as its piece de résistance a gaudy MiMo sign in five-foot-high gold letters.

A little more than a year ago, the Lido was still operating as an "old-lady spa," according to David Lemmond, the hotel's new general manager. "When we came onto the property, the little old women were padding around in their sundresses and robes, playing cards and getting treatments. Rooms went for $79 a night." Balazs adds, "The owner of the hotel, Chuck Edelstein"—who bought the Lido with his father and brother in 1963—"still stood at the stairs to the dining room and greeted each lady by name when they went in for dinner. There were boxes of matzos on the tables. It was really a time warp. South Beach exploded all around this place, and here, because it's on Biscayne Bay, a few blocks inland from Ocean Drive and Collins Avenue, time seemed to stand still."

Balazs recalls, "For several months, as we were constructing the model rooms for the redesign, the old ladies kept poking their heads in and looking at what we were up to. They all liked the new look, so we said, 'Come back when we are finished. You're welcome here.'" When and if they do return, they will not recognize the place—except for three rooms that are being kept intact with green wall-to-wall as wry reminders of the original Danish-modern look.

'The idea behind the Miami Standard is to take it back to its glory days as a spa but to make it the antithesis of what is in South Beach," says Balazs, who was helped on the project by designer Shawn Hausman, who was responsible for the first two Standard designs. "It has a kind of Scandinavian theme—the last thing you would expect to see in a tropical climate. The most salient feature is that every material is natural—light wood surfaces, embroidery details, woven mats for carpeting. The rooms are surrounded by herbal gardens. It is the absolute opposite of the Hollywood and downtownL.A. Standards, and it should be. Those hotels, which are in very urban settings, have a lot of plastics and harder-edged industrial materials. This hotel is on an island."

Balazs stands on the tar-paper roof of the hotel, overlooking the bay and a gigantic ditch, where in a few weeks there will be a spectacular swimming pool. Yachts and speedboats go by. Overhead, a 747 flies out to the Atlantic. The grounds of the hotel are currently in disarray, but his vision for the place is crystal clear: "I was inspired by ancient bathhouses, and I wanted to take off from the communal notion of Roman baths and Scandinavian spas. But we are going to remove the labor aspect, so you can go and do the treatments yourself. This is because the spa experience in L.A. and New York has become expensive—you can't go to a spa without it costing you $100 an hour. The idea is to get you back to the time when going to the baths was a communal experience, where friends gather and you can help each other bathe."

Balazs has entrusted the development of the spa for the Miami Standard to 33-year-old identical twins Jason and Jared Harler, tattooed, Seattle-bred nature boys interested in alternative healing and the spiritual side of public baths. There will be an ambitious wellness program at the hotel, including classes in Kundalini and other forms of yoga. Guests will be able to take part in an array of aquatic therapies, including the "Falling Water Column—a two-inch column of water falls 15 feet, landing where you need it most," according to Jason Harler. The therapeutic muds will be imported from Reims, France, and from Utah. Near the Carraramarble mud-bathing slab will be "the S&M hose," with which you can spray down a friend with a high-pressure jet.

Balazs has taken many research trips, including one to Les Prés d'Eugénie, a spa near Biarritz, where he got the high-pressure-hose idea. In New York he likes to visit the 10th Street Baths, a slightly unsanitary holdover from the days when Russian-Jewish bathhouses could be found on many blocks of downtown Manhattan's East Side.

Balazs undertook his First development project in Miami seven years ago—the renovation of a small hotel at 8th Street and Washington. He ultimately sold that building and turned his attention to hotels in L.A. and New York. Now, he feels, the time has come. "For me, Miami has become a place that evolved from a destination to a real city. People say, 'Is Miami in?' That's like asking, 'Is New York in?'" says Balazs, looking out on the bay from the dock of the new Standard. "We are standing in the heart of a major city, and we are on water. You can boat out among skyscrapers. You will be able to take a kayak from here into the bay. You can go swimming. You can go to the beach. And Miami is also becoming a major art center. I mean, there is no denying the charms of Miami."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now