Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

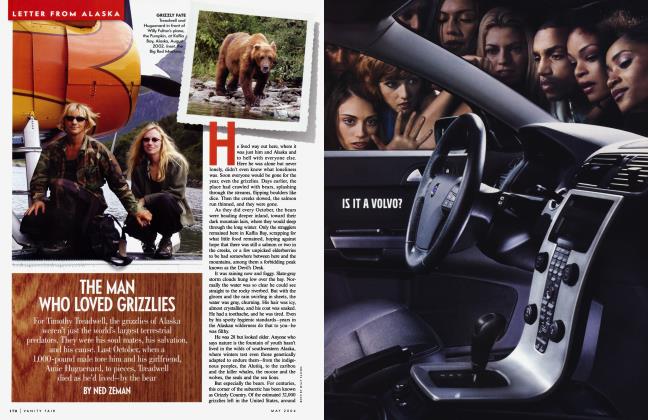

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter rushing back from V.F.'s Oscar party to attend the tear-filled finale of the Martha Stewart trial, the author reports on the public spectacle, the private pain, and a remaining mystery: the role of Mariana Pasternak, who without any prodding sealed her best friend's fate

May 2004 Dominick DunneAfter rushing back from V.F.'s Oscar party to attend the tear-filled finale of the Martha Stewart trial, the author reports on the public spectacle, the private pain, and a remaining mystery: the role of Mariana Pasternak, who without any prodding sealed her best friend's fate

May 2004 Dominick DunneIn the upstairs rooms of the Old Federal Courthouse in Manhattan where Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic, with their lawyers, families, and friends, were sitting out the time waiting for the jury to return with a verdict, there was no sense of alarm or anxiety in the air. It was a Friday afternoon, March 5. The consensus of opinion among the lawyers was that the jury, which had been out less than two days, would continue deliberating into the next week. Bacanovic was playing Scrabble with the writer Christopher Mason, a close friend, while one of his lawyers looked on. At 3:15 word came that the jury had sent a note to Judge Miriam Goldman Cedarbaum, but there was nothing special in that. Over the previous two days, they had sent in several notes, asking for a transcript of this witness's testimony or requesting to see that document, so the defendants and their friends assumed that this was just one more such request, all of which required their presence in the courtroom. They were so unconcerned that Martha Stewart, on her way to the door, looked down at the Scrabble board and said to Christopher Mason, "'So-so' is not a word."

Once they were inside the courtroom, however, they could all see that the back wall was lined with federal marshals. Simon Crittle, who was covering the trial for Time magazine, whispered to me, "CNN is reporting that a verdict has been reached." We sat and waited, and waited. There was no chitchat, just increasing nervous anticipation and repeated whispers that the jury had concluded their deliberations. Finally Judge Cedarbaum entered the courtroom. A small woman of 74, she had run a tight ship throughout the proceedings. Eminently fair, I thought. She knew the law, she never missed a beat, and she was not reluctant to move along, argue with, or contradict the lawyers on both sides. "There is a verdict," she said. Then the jury entered. It was noted by one and all in the media that not a single juror looked in the direction of Martha Stewart. That is never a good sign.

I, for one, was shocked at the verdict. I didn't expect an outright acquittal, but I had been clinging to the hope of a hung jury. Throughout the trial, along with my colleague Anne Thompson of NBC News, I had mistakenly picked out juror No. 6 as being sympathetic to Martha Stewart. I would have liked to talk to her, or hear her reasoning, but she was not among the jurors who would subsequently go on television to discuss the case. I knew very well that the charges against Stewart and Bacanovic were serious, but to my mind they were inconsequential compared with the massive corruption practiced by the big boys at Tyco, Adelphia, Enron, and WorldCom, who are accused of lining their pockets with hundreds of millions of dollars from their companies and their stockholders. When Judge Cedarbaum read out guilty on four counts for Stewart and guilty on four counts for Bacanovic, there was a collective gasp in the courtroom, and I was part of it. Some reporters ran from the courtroom to signal the verdict to the television and radio crews outside, across Centre Street. Others raced to the few pay phones in the courthouse—cell phones are not allowed inside— which they had underlings commandeering for them, to call their newspapers.

Neither of them flinched as their lives crashed to pieces.

In the courtroom where Judge Cedarbaum had maintained perfect decorum for six weeks, with the help of U.S. deputy marshals Nick Ricigliano and James Lyons, pandemonium broke loose. Stewart and Bacanovic, whose deportment and dress had from the beginning been admirable, remained stoic, looking straight ahead, without any change of expression, as the word "guilty" was repeated eight times. Neither of them flinched as their lives crashed to pieces in front of us all. Then each of the 12 jurors was polled by name. "Is this your verdict?" asked the judge. "Yes, Your Honor," each replied. The defense lawyers looked stunned. The prosecution lawyers did not for a moment flaunt their victory with smiles or pats on the back. You could hear people crying. Alexis Stewart, Martha's 38-year-old daughter, with whom she has had a complex relationship over the years but who had been a loyal and ever present supporter at the worst point in her mother's life, leaned forward and broke down in sobs. Curiously, it was Alexis Stewart who had brought both Sam Waksal, a onetime suitor, and Peter Bacanovic, a college classmate, into her mother's life. I also had tears in my eyes. I'd had dinner with Bacanovic and two close friends of his just a few nights before, so I was aware of the terrible fear he had had of the moment he was now experiencing. I had also received a note from Martha a few days earlier, thanking me for being at the trial and saying that we would have a good long talk when it was over. I took that to mean that she would give me an interview and that she was pretty confident she was going to win.

Surrounded by guards and security men, the two defendants left the courtroom by the center aisle. Bacanovic, in a daze, grabbed my arm as he walked by. Stewart nodded to distraught friends but kept moving, head held high, showing not an ounce of defeat or remorse. Even in the corridor outside the courtroom, surrounded by solicitous admirers, she kept herself totally together. It is one of those Joan Crawford-as-Mildred Pierce traits about her that infuriate people. I simply couldn't imagine these two, friends both, going to prison. When one friend tried to kiss her, she said, "I don't need that." She has an innate sense of composure. She and Alexis neither embraced nor touched. It wasn't until they arrived back in their reserved rooms on the fourth floor that they could drop their masks. Christopher Mason, who has written a book about the Sotheby's-Christie's price-fixing case entitled The Art of the Steal, was there with Bacanovic's family and lawyers. "It was like a wake," he said. "Peter's father was weeping. There was a stunned silence. Peter kept saying, 'She could have settled. She could have settled.'" And she could have, as we subsequently found out.

Even though I was a friend and supporter of both defendants, I had trouble believing that Martha really had a stop-loss order with Bacanovic to sell her ImClone stock if it fell below $60 a share. The prosecutors had presented a very compelling case, with three witnesses who delivered knockout blows to Stewart: Douglas Faneuil, Bacanovic's assistant; Ann Armstrong, Stewart's secretary; and Mariana Pasternak, Martha's best friend of 20 years. Faneuil, who had disliked Martha because of the way she had spoken to him at various times, initially got involved in the stop-loss story, before deciding to cooperate with the prosecution. The other two, between them, pounded the nails into Martha's coffin.

Trials about financial malfeasance tend to be boring compared with murder trials, but this one had moments of high drama. Douglas Faneuil, who was branded a turncoat, was expected to be destroyed on the stand by Bacanovic's lawyer, but the baby-faced former assistant, who was 26 years old when he made the telephone call to Martha Stewart to tell her illegally that the Waksals were dumping their ImClone stock, held his own and won the day for the prosecution. Ann Armstrong, who worshipped Stewart, provided the damning information that Martha had sat down at Armstrong's computer and altered a message from Bacanovic concerning the ImClone stock. She said that Martha instantly wanted her to change the message back to what it had been, but the damage had been done. The prosecution ascribed the action to consciousness of guilt. In the end, Mariana Pasternak's testimony sealed Martha Stewart's fate. Pasternak had been present on the tarmac in San Antonio, where Martha's private plane landed to refuel, when Martha received the call from Faneuil. She told the jury that Martha was speaking "in a raised tone of voice" on the phone. She testified that she and Martha did not discuss the telephone call for several days. That never sounded right to me. They were longtime best girlfriends, traveling together on a private plane. I found it extremely hard to believe that the subject of a critical phone call didn't come up until three days later, when they were chatting on the balcony of their $1,500-a-night suite at Las Ventanas, the Mexican resort where they were passing a few days before joining socialite Jean "Johnny" Pigozzi's yachting party in Panama.

At the conclusion of the trial, a Westport, Connecticut, acquaintance of both Pasternak's and Stewart's contacted me. All three ladies had served on a charity board for the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp, Paul Newman's retreat for children with cancer. They were also all members of the Fairfield County Hunt Club. My caller said that Mariana would forever be remembered as "that false friend who did in Martha Stewart." Martha was godmother to two of Pasternak's daughters, Monica, 20, and Lara, 17. In the course of their long friendship, Martha had taken Mariana on trips to Peru, Egypt, Brazil, the Galápagos, and other foreign spots. Private planes, big yachts, and fancy jet-set friends were all part of the package that Mariana accepted from her friend. Recipients of largesse from rich friends, I have found, often cease to be grateful. Divorced from Dr. Bart Pasternak, Mariana is a real-estate agent in Westport.

John Lehmann reported in the New York Post that Pasternak is being sued by a local builder named Juno Filho, of Southern New England Renovations, for an unpaid bill of $83,000. Two federal tax liens have been filed against her property for $380,000. For someone that deeply in debt, the chances of taking luxury vacations on her own were slim. "She has lost a really good friend," said a member of Stewart's staff.

Lehmann also reported that Stewart had paid tens of thousands of dollars toward Pasternak's legal bills "before she began speaking with the government in 2002 about Stewart's ImClone sale." Betrayal is such a dramatic word, but the prosecutor didn't need to prod Pasternak to quote Martha saying, "Isn't it nice to have brokers who tell you those things?"

On her own she delivered the coup de grâce that would become the most widely quoted line of the trial. The next day on cross-examination she backtracked a bit, saying that maybe she had just thought Martha had said that, but, once again, the damage had been done. One day it will make a great scene in a movie: two best friends, one a defendant in a trial that could send her to prison and the other in the witness-box testifying against her. Pasternak never looked at Martha. I think it's safe to say that Stewart's long, beneficent friendship with Pasternak is over and out, and unlikely to be resuscitated when Martha emerges from whatever fate awaits her. And I wonder if Johnny Pigozzi is going to want Mariana on his yacht again anytime soon. As for those private-plane trips to exotic places, she can forget it.

There is an interesting part of the story that has received minimal attention. The fateful telephone call from Douglas Faneuil to Martha in San Antonio telling her that Sam Waksal was dumping all his stock in his biotechnology company, ImClone, was made on December 27. Late that same day, there were rumors on Wall Street that Waksal's drug Erbitux was not going to be approved by the F.D.A. In Westport on December 28, Dr. Bart Pasternak, Mariana's ex-husband and the father of her daughters, sold $600,000 worth of ImClone shares— far more than Martha sold.

"Peter Bacanovic kept saying, 'She could have settled.'"

Late in the trial I sneaked off to Los Angeles to attend the Vanity Fair Academy Awards party, because Oscar night has been a ritual of my life for 40 years. I left New York on Friday, when there was no court, so I missed only the following Monday, which my colleagues filled me in on. As for the Oscars, I liked Lord of the Rings, but I got sick of having it win practically every Oscar of the evening. I was more inclined toward Mystic River, and I was thrilled that Sean Penn won for best actor. It's always been the best weekend of the year in Hollywood, like a four-day New Year's Eve, and it was again this year, from Betsy Bloomingdale's glittering dinner party for the New York crowd who'd flown out for the occasion to Ed Limato's annual tent party, where I missed seeing Mel Gibson, to Barry Diller and Diane Von Furstenberg's annual picnic with the world's most gorgeous young people, to Wendy Stark's beautiful memorial service for her father, Ray Stark—a movie mogul in the tradition of the great ones such as Louis B. Mayer, Darryl Zanuck, and Jack Warner—in the sculpture garden of his Holmby Hills estate, to the Vanity Fair party itself. Martha Stewart was the topic of conversation everywhere. The Vanity Fair party is a long, fabulous event, with everyone dressed to the nines, which stretches from five o'clock in the afternoon to three or four in the morning. I'm far too old to get excited over seeing practically every movie star in Hollywood pour into Mortons that night, but I still do.

Early the next morning I got on a private plane to get back to Martha Stewart's courtroom for the closing arguments. I was sated with my celebrity-filled weekend. By contrast, I learned, the jury at the Stewart trial were terribly put off by the celebrities who came to offer support for her, including Rosie O'Donnell, Bill Cosby, and Brian Dennehy. I suppose the comfy cushions provided by Martha's people for the hard wood benches where her family and friends sat didn't help matters.

Ray Stark was in the great tradition of Mayer and Warner.

Martha didn't take the stand. I think she would have been great if she had, and she could have shown a side of herself that people don't see, but I know that her decision not to testify, which was strongly advised by her lawyer Robert Morvillo, was the right one. The prosecution could have brought up things from Stewart's past unrelated to this trial that might have made things worse for her. Morvillo didn't even put on much of a defense, just a 20-minute appearance by a lawyer who had taken notes at a meeting of F.B.I. agents with Martha, and that was it. Morvillo used the phrase "confederacy of dunces" and said that Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic were far too smart to have come up with such an impractical alibi as the stop-loss order. But his summation was inadequate. It implied that the prosecution didn't have a case, and by then we all knew that the prosecution had presented a very good case and three very strong witnesses. Ironically, his summation seemed arrogant in its brevity, when "arrogant" had been the word used so often in the press and in the courtroom to describe his client.

I believe that Peter Bacanovic felt some discontent with Martha Stewart, but he left it unspoken. As one of his closest friends, who cried in the courtroom at the verdict, said to me that night, "Unfortunately, this could have so easily been avoided if Martha had just accepted the government's offer last year of pleading guilty to a minor charge. That would have saved her, and Peter, from this horrible mess. Instead, it's ruined both their lives. I guess when you've been on a long winning streak like Martha you think you're invincible. Tragic mistake."

Totally distraught, Bacanovic stayed in New York only long enough to report to his parole officer on the Monday following the verdict. Then he flew to California to stay with a friend, out of sight, with no plans to return until the day before his sentencing on June 17. I talked to him before he left, and he described the total experience from December 27, 2001, until the verdict on March 7, 2004: "At every turn, when it seemed it could get no worse, the downward spiral continued. The devastation to my life and the pain that my family and my friends have endured defy description. Yet I have been true to myself throughout, and I look forward to the day when this intense pain will end. This is what I've lived through for the last two years."

On the night of the verdict, I went on The Abrams Report, NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw, and Larry King Live, either alone or on a panel. No two ways about it, Martha's guilty verdict was the No. 1 story in America that night. I was amazed by the glee that some people felt over the downfall of one of America's most successful women. A woman of my acquaintance, with whom I have a sometime e-mail correspondence, ceased our friendship (by e-mail) because she had been told that I spoke up for Martha Stewart on the Larry King show. She went into a diatribe of hate against Martha and said she hoped she got 20 years.

To me Stewart's possible punishment does not fit the crime. Susan McDougal was on Larry King the same night I was. She had served three years in prison during the Clinton administration, and she described the daily humiliation for a woman of being behind bars. She said they take everything away from you except your glasses. She told of rectal and vaginal examinations after you had had visitors. In an interview with Andrea Peyser in the New York Post, Leona Helmsley, who did time in the early 90s at the correctional institute in Danbury, which is probably where Stewart will be sent if Judge Cedarbaum gives her jail time on June 17, had this advice for Martha: "Darling, they're not there to torture you. They're there to reform you.... I think it helps people to go there." She further advised, "And, for once in your life, follow the rules."

I never had the long talk with Martha that she suggested in her note, because everything changed with the guilty verdict. I did talk with her trial publicist, Anna Cordasco, and asked her if Martha would describe to me her feelings at the moment she heard Judge Cedarbaum pronounce her guilty. I later learned that Martha had complied, but—wisely, I suppose—she showed her lawyers what she had written, and they advised her not to send it to me, as it might affect their appeal after she is sentenced on June 17.

For some reason, I'd never been to a Kmart, but I headed for one in Connecticut shortly after the verdict, and I bought four Martha Stewart pillows and a set of Martha Stewart sheets and pillowcases that I didn't really need. I just wanted her to stay in business.

Martha may be down, but she's not out. When you go through a life-changing experience, as she just has, you ultimately emerge in one of two ways: either you learn from it or you're destroyed by it. One of her colleagues told me that since the trial "she is totally at work, full steam ahead, as always." My prediction is that Martha Stewart is going to soar again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now