Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSOUL SISTERS

Patt Derian, Rose Styron, and Kerry Kennedy devote their political— and social—clout to unnerving the most savage dictatorships

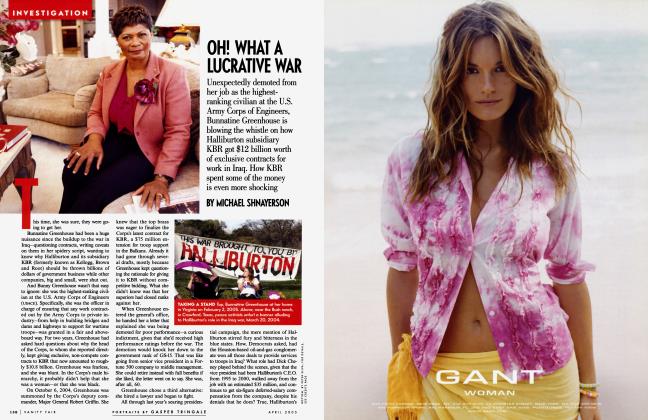

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

New Society

It isn't pleasant work, really. Lots of dead bodies, mutilated by torture; posses of Third World military police, guarding you with ill intent, bugging your room, following you to see whom you meet. Far easier to stay at home and give money to the human-rights causes whose pitches crowd the mail. Yet there must be something in it: Patt Derian, Rose Styron, and Kerry

Kennedy continue to fly from one troubled country to another on dizzying schedules, challenging repressive leaders on their treatment of dissidents and bestowing upon those dissidents awards for courage and perseverance in the face of flagrant human-rights abuses. Friends, traveling companions, and fellow board members, role models for one another, they form a troika of frontline volunteers in a cause that has helped revolutionize the world.

That they are all women is more than coincidence: the human-rights movement in America, for better or worse, has been undertaken largely by women. Many work full-time for Amnesty International or for the New York-based Human Rights Watch, which monitors violations of the Helsinki Accords. Last November, it was a full-timer—Jeri Laber, executive director of Helsinki Watch, one of six "watch" groups under the H.R.W. umbrella—who went to a Prague restaurant to meet her longsuffering Czech dissident friends Jiri, Rita, and Jan, only to be arrested in a surprise police raid. Luckily, one dissident was late in arriving, and his fellows were able to yell from the van, "Hey, Vaclav—get lost!" Four weeks later, Jiri was the foreign minister, Rita was appointed the new ambassador to the United States, Jan was a first deputy prime minister. And Vaclav Havel was the new president of Czechoslovakia. "One reason human rights draws a lot of women is that it doesn't pay well," says Laber with wry cynicism. "And women are more willing to make sacrifices."

The volunteers who don't need to work are, in a sense, removed from that decision. And yet the same compassion drives them. A feminine response to the masculine madness of war? A maternal caring for the victims of abuse? An awareness that women may be more persuasive in confronting torturers who are almost invariably men?

For Derian, who stands as nothing less than the role model for an entire generation of younger women in the field, human-rights work grew out of civil-rights work. In 1959, as a Mississippi housewife with three children, she found herself in a society polarized by the Brown v. Board of Education decision. She saw whites unite to keep schools segregated and, later, to close them rather than subject their children to integration. "All of a sudden, there you were," says Derian. "You had to decide if you were going to live up to your principles—or accept that you didn't have any at all."

Derian, by all advance accounts, is one brash southern character: simultaneously gracious and blunt, ladylike, and fully capable of sitting across a table from an admiral in an Argentinean naval academy and firmly insisting that "I know there are people torturing people right under us, Admiral. And I know you're responsible!"

Between trips to Hong Kong for the International Rescue Committee, to monitor the detention camps where Vietnamese boat people have been penned like war criminals, Derian stops long enough for lunch at her temporary new home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where her husband, journalist and political pundit Hodding Carter III, is teaching a public-policy seminar at Duke. It seems not untypical that Derian has been defeated by the lock mechanism on the front door and is reduced to going in and out through the garage. Or that the red raincoat in which she greets a visitor remains on for the next three hours as she putters about the kitchen and talks. Strangers might take Derian's distraction for daffiness, but this would be a serious error. It's just that next to human rights nothing else seems important enough to fret about.

"I know there are people torturing people right under us, Admiral. And I know you're responsible!"

£ I n the midst of all the awfulness—and I the wild humor that goes with awfulI ness—we realized what an incredible thing had happened to us," Derian recalls of the segregation issues that began to dominate her life. As the sixties unfolded, her involvement grew from local to national politics. She went on to work as a deputy director in Jimmy Carter's first presidential campaign, and when Carter, as president, asked her to serve in a newly minted human-rights post, she moved to Washington. "She showed at the beginning what that office should be doing," says Bob Bernstein, former C.E.O. of Random House, who founded the Fund for Free Expression (now part of Human Rights Watch) fifteen years ago. ''She showed it should serve not only as a moral voice but a voice about America's greatest institution, which is its ideas. She stood up to tyranny, and called the world's attention to it. ' '

Just days into the job, Derian realized that the mounds of cables on her desk weren't enough to go by; she herself would have to travel. An unexpected invitation came from the State Department, traditionally the backer of ''democratic" juntas with appalling humanrights records. ''The department's LatinAmerican bureau made a blunder of wonderful consequences for me," Derian explains. ''They decided that if they sent the little Mississippi housewife down there to talk to the generals I would understand the terrible problems they were having."

The trip became a template for all that followed. In one comer: the State Department, assuring Derian that the rumors of torture under the military juntas were false, spread by guerrilla factions, and that, even if they were true, torture was the only reasonable policy in a war with such hideous foes. In the other corner: the generals themselves, talking first in earnest tones about the history of their country and their constitution, then about how their very way of life was under siege. "When you're running a state like that, ' ' observes Derian, ''you really have to make the people who are threatening you inhuman."

First stop was El Salvador, where she met with General Carlos Humberto Romero and his colleagues. Derian had interviewed many witnesses and victims in the days before to learn what specific forms of torture were prevalent—and to be sure that when she made an accusation she wasn't overstating the case. "When you talk to the people whose policy it is to use those things, you have to know what they use, and you have to say it to them, and you have to be right," Derian explains. "You have to say, 7 know you're using the horse.' "

The meeting grew increasingly tense. Derian found she had to pay attention to every gesture and inflection, in the slow, subtle effort to push the generals from absolute denial to some admission that would lead to real conversation. At the end, Derian brought up the subject of death threats received by foreign priests from a paramilitary group. "You know," said General Romero sullenly, "it's a good thing they sent a woman down to talk about these things. Men's voices are too rough."

"In a way I understood what he meant," says Derian. "Most of those negotiations between government officials become a very macho game. Someone's got to win; men insult each other in snide ways where you can't actually be confronted by it. Others want to establish ascendancy—who's up, who's down. I just want to think and persuade and change what they do." The death threats eventually stopped.

During the tenure in which she carried the Carter human-rights standard—and the mandate to push for military and economic sanctions—to some twentyfive countries, Derian stared down dictators and almost invariably won, at the least, better treatment for political prisoners. Inevitably, Derian heard terrible stories from victims or their families. She learned not to cry when she did. "When you're talking to people whose children have been taken, or who've had the body of a dead daughter delivered to their door with signs of gross torture, there is no way you can understand the depth of their suffering," she says. "And it was my feeling that I didn't get to piggyback on their pain. The reason these people risk their lives to talk to you is because they think something can be done. They need your head, not your heart, and if you work for the government, they need your connections. And when you go to bed at night, you have to make up your mind that you have to go to sleep and not think about it."

With the onset of the Reagan years, Derian carried on as a volunteer. She served on the boards of Amnesty International and the Fund for Free Expression. She watched with amazement as the Reagan administration did its best to undo the work she had done, eventually installing hard-liner Elliott Abrams in her post and using the office as a propaganda tool. And she traveled, meeting with heads of state as often as she had in the past. "I think they saw me for the same reasons they'd see Oriana Fallaci," she offers. "They were curious, and I was candid with them, and that was a rare experience for them." To much of the Third World, she had become one of America's few heroes— along with Senator Ted Kennedy, who remains the Senate's most active proponent of human rights abroad. When South Korean opposition leader Kim Dae Jung flew home after a long exile, it was Derian who accompanied him, not some State Department bureaucrat.

"I know something terrible will happen when you land," worried a KoreanAmerican supporter as they boarded the plane. A year and a half earlier, Benigno Aquino had been assassinated in identical circumstances.

"Nothing will happen," Derian assured him. "If it does, I'll scream." The plane landed, Derian and Kim Dae Jung stepped cautiously into the terminal chute, and suddenly a flying wedge of South Korean agents came at them. Derian was crushed up against the wall of the walkway, too startled for a moment to react. Then she remembered she'd promised to scream. "It wasn't a bad scream," she says. "They heard me inside, and the press microphones picked it up, and not long afterward Joan Baez called up and said, 'Gee, Patt, I recognized your scream on television.' "

Kim Dae Jung survived the roughingup but was put under house arrest. Derian's next trip to South Korea was on behalf of another dissident, Kim Keun Tae, who was imprisoned. She presented him with a human-rights award—the tactic that has created perhaps the movement's most effective, stirring international publicity, ensuring a winner's safety and shaming a repressive government into holding back. Along with her now were two staunch colleagues: Rose Styron and Kerry Kennedy.

Like ballplayers in a national league, human-rights activists bounce from team to team. Often they play for two or more at once; everyone, after all, is on the same side. Thus it is that Rose Styron, wife of novelist William Styron and a twenty-five-year veteran of civiland human-rights work, can tick off half a dozen boards on which she's served at one time or another, from Amnesty International to PEN'S Freedom to Write Committee. As with Derian, her humanrights trips have taken her around the world—though her role has generally been confined to meetings with dissidents and helping extend the international network of human-rights groups. A deeply gracious woman whose friends tend to speak of her in awed tones, Styron brings to the task a personal network that is considerable indeed: literary and social circles that begin at their farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut, where she and her husband count among their neighbors Mike Nichols and Diane Sawyer, Philip Roth and Claire Bloom, Francine du Plessix Gray, Woody Allen and Mia Farrow; a Manhattan crowd that includes Bill and Wendy Luers, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and his wife, Alexandra; a summer life on Martha's Vineyard with old friends like Art Buchwald, Kay Graham, Mike Wallace, and Carly Simon. A poet, Styron keeps in touch with fellow poets here and abroad and has translated Soviet writing; her first humanrights trip, in 1968, was to the Soviet Union to attend a writers' conference and smuggle dissident poets' work to Western publishers. She took that trip with her husband, but since then, with rare exceptions, she has traveled on her own.

In Chile, Styron sewed the names of desaparecidos into her skirts and a double-lined shoulder bag.

"Bill was interested in civil rights in the U.S., and in the death penalty, before I was, and in a sense he brought me into that in the late fifties," Styron admits. "About Vietnam we had equally strong feelings, and worked together against it. But about international issues, I think it's fair to say, Bill's interest came from me."

Rose returned from her first Soviet Union trip appalled by stories she'd heard from dissident writers of brutal treatment in the gulags. At the time, the only human-rights group to join was Amnesty International, which had been started in London not long before and had two small U.S. offshoots, one in New York and one in San Francisco. "I sat on a cushion quietly for a few sessions," Styron recalls. "Then I began to help write the letters they were sending to imprisoned writers."

Styron's baptism as a frontline human-rights activist was in Chile in early 1974, not long after the military coup that toppled the Allende government. Her sponsor was the National Council of Churches, for which she hoped to gather information on prominent members of the Allende government who had disappeared. At this time of mass disappearances, when even children were tortured, sedated, put aboard transport planes, and then dumped out over the ocean, Rose Styron and her then seventeen-year-old daughter, Susanna, arrived as high-class tourists. The Horman family—whose story was the basis for the movie Missing—were also in Santiago, searching for their son.

Just making contact with the priests who could provide information on the desaparecidos was hard enough. Styron had had to memorize long lists of their names, rather than risk their safety and her own by bringing any documentation. When she located a contact, she had only her character to convince him that she was bona fide. And, of course, despite her cover, she stood out as an American and was followed everywhere.

As it happened, when she finally found the Chilean priest who had the names she needed, the information he gave her was both on microfilm and typed on paper; Styron sewed the documents into her skirts and a double-lined shoulder bag. "It's pretty clear I would have been imprisoned if they'd found the records," she says matter-of-factly. "And this would also have led to reprisals against the families named."

By that point, government agents had a strong suspicion that the Styron women were up to something; they just didn't know what. At the airport, the Styrons were searched. Rose had hidden additional documents in her bra, under which she'd worn a bathing suit so the papers wouldn't crackle. "I felt scared, of course," Styron remembers. "But I also felt so stupid for taking Susanna with me. I had exposed her to real danger." Mother and daughter emerged safely from the search, to the relief of Chilean friends waiting discreetly on the airport's mezzanine level.

A dozen trips later, Styron has come full circle, focusing once again on the Soviet Union. Last year, just before his death, Andrei Sakharov asked her to help him form a group, with Gorbachev's blessing, to draw up new guidelines for the Soviet penal system, emigration, and immigration. While there, she agreed to make a comparison study of the American prison system. "They asked me for all the information I could gather on political prisoners in the U.S.," Styron recalls with a smile. "I said, 'What do you mean?' The whole idea of political prisoners here seemed a foreign notion."

Styron isn't yet persuaded, but her first inquiries have troubled her. The federal penitentiary at Marion, Illinois— the country's most secure—houses several of the prisoners deemed "political" by the Soviets. Many are minorities associated with radical political groups; whether they are guilty or not, the harshness of their treatment seems sorely disproportionate to that of other prisoners. Styron plans to visit Marion, and she plans to visit the Florida holding pens where illegal immigrants, particularly Haitians, are subjected to what the Soviets feel is also abusive treatment. "The slant is new for me," she admits, and as yet it's unclear what one nicely dressed woman can accomplish at the gates of a detention camp. At the same time, with publicity and persistence, Styron and other members of PEN'S Freedom to Write Committee helped stymie the U.S. government's effort to deport Margaret Randall, an American-born radical writer who moved to Mexico and made the mistake of giving up her U.S. citizenship in order to work there. When she returned to the United States, she found she was officially unwelcome because of her political beliefs.

Various as Styron's ties are, they have a way of playing off of one another. It was in 1986 that Sting, Peter Gabriel, and the members of U2 staged their "Conspiracy of Hope" tour in the U.S. to raise interest in Amnesty International. The tour was a bang-up success, and the rockers began talking of a world tour. But they needed a corporate sponsor. All but one of the prospects approached said no without equivocation; Reebok said no, but gently. On a month's stay with her husband in California, Styron hosted a meeting with the local Reebok executive—a Cuban, as it turned out, with a sensitivity to humanrights issues.

Others were at the meeting, and all helped make the case, but Styron was the one non-staffer among them: more objective, or so it seemed, ever gracious, quietly persuasive. Eventually, Reebok's chairman, Paul Fireman, made a commitment that amounted, by the tour's end, to $10 million. "The aura of Rose is so benign," says Wendy Luers, "that in the inevitable chaos and conflicts of human-rights work there is this wonderful glowing peacemaker who makes everything right."

Styron tagged along for much of the tour, watching from backstage as Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman, and Youssou N'Dour played to stadiums full of young Spaniards or Argentineans holding candles, and groups of mothers of the disappeared danced slowly onstage. While in Argentina, Styron joined a group of young forensic experts—doctors and anthropologists—on their grim pilgrimages to mass grave sites. She watched as they dug up the skeletons of the disappeared and applied ingenious new forensic methods to identify the dead. One aim was to establish the genealogy of orphaned children, then determine who the children's still-living grandparents were. Last year, the group was able to match thirty-six orphans with surviving members of their families.

"Look them in the eye" Derian counseled Kerry Kennedy about dealing with oppressors over dinner.

By then Styron had helped persuade Reebok to sponsor annual awards for human-rights activists under thirty who have demonstrated unusual courage. This year, one of the forensic experts, Mercedes Doretti—an anthropologist whom Styron had accompanied on the Argentinean trip—was among the winners.

Oddly enough, Styron doesn't seem any more depressed by the work than Derian does. The question actually makes her laugh. "It's incredibly heartwarming work," she says, "because of the spirit of the survivors. They're the most interesting, remarkable people in the world today. Often, too, they're literally the most educated and brilliant, because those are the ones often targeted. But, also, a lot of these people, because they have spent time in solitary prison cells, were forced to look into themselves, to find new reserves of strength, and to consider how man reacts to pain and deprivation. And you know what?" she adds. "They all have this wonderful sense of humor. Because they only take the really serious things seriously. The rest of life, for all of them, is just so exhilarating."

It lue-eyed and blonde, with her father K Robert's dimples and a shy, sweet Ir smile, Kerry Kennedy, at thirty, is living the best life she knows how to live: serving as the head of the Bostonbased Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Center for Human Rights. It was as a student at Brown that Kennedy first worked for human rights, spending the summer of 1982 in the Washington office of Amnesty International. Her job was to investigate abuses perpetrated against Salvadoran refugees by U.S. immigration officials. Her inspiration was Rose Styron.

Kennedy also came to admire the American lawyers who had committed themselves to the cause; they made her want to go to law school. After graduating from Boston College's School of Law, she eventually chose to work full-time for the R.F.K. Memorial, the Washington, D.C.-based foundation that for years has bestowed awards in journalism and the arts. Beginning in 1984, the Memorial added a human-rights award to its lineup. An international advisory committee including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, and Czeslaw Milosz was drawn up to tender nominations. The panel of five deciding judges, all Americans, included Patt Derian and Rose Styron. Two years ago, Kerry put her own stamp on the foundation's human-rights work by establishing a separate Center for Human Rights to offer follow-up support to the annual humanrights-awards winners.

For Kennedy, the South Korea trip with Derian and Styron was a fascinating first, not only because of what the more seasoned women taught her about how to conduct such missions ("Look them in the eye," Derian counseled Kennedy about dealing with oppressors over dinner, "until they start running on—then drop your fork") but also because Kim Keun Tae and his wife, In Jae Keun, became the first recipients of the Center's follow-up help. Incarcerated at the time of the Americans' visit, Kim Keun Tae was freed six weeks later—a full two years before his prison term was due to expire. Forty-five other political prisoners were released as well. "For me it's so worthwhile because you're working with people who literally will be tortured for the right to vote," Kennedy says, her excitement getting the better of her shyness. "There's an incredible sense of dignity and honor about them. They're not unlike the ancient Greeks: a bedrock belief in honor, in nobility, in being noble."

A more recent recipient is Gibson Kama Kuria, a lawyer imprisoned in Kenya. Kennedy traveled to see him last year, armed with her latest Center for Human Rights award. The Kenyan government, proud of its benign image in the West and terribly dependent on Western safari dollars, was shaken to the core by Kennedy's visit. "What you have to understand," says one activist who went along on the trip, "is that many Africans are very fond of the Kennedys; they see Kennedy's presidency as a time of U.S. assistance, of the Peace Corps, the whole civil-rights movement. Even in remote villages, you'll find pictures of the big three: J.F.K., R.F.K., and Martin Luther King Jr. So for a young Kennedy—a woman, no less—to criticize the government was a real slap in the face."

Despite her group's success so far, Kennedy's guard falls back in place when asked how it makes her feel to have helped. "Oh," she says quickly, "you can never say, 'It's because of us.' Anyway, for me it's not what we're doing. It's the woman with three kids who's getting raped in Salvador because she's looking for her husband in jail—and then keeps working for his release."

T ready? Perhaps. But it doesn't seem I so on the night of the second annual I Human Rights Watch dinner in New York. After cocktails in the vaulted pink marble lobby of the Equitable building—as grimly authoritarian a tower as ever rose in Manhattan—the crowd files down to a basement theater to find ten people onstage seated on folding chairs. They are human-rights monitors from ten countries who, being honored this year, look quietly back at the audience that is looking at them. In the last year, fifty-three others in the worldwide network of monitors have been killed, eight have disappeared, and scores have been jailed.

Rose Styron is in the audience. So are Kerry Kennedy and Patt Derian, and a surprising number of famous faces: Steve and Courtney Ross, Saul and Gayfryd Steinberg, Marvin and Lee Traub, Kay Graham. Human rights is clearly a cause whose time has come, and not just in Eastern Europe. Is it any accident that just days later a startlingly slick sixtysecond commercial for Amnesty International will begin appearing on primetime television, with star turns by Glenn Close, Meryl Streep, and Sam Waterston, among others?

This year's honorees are introduced: Larisa Bogoraz, a small, gray-haired woman in black from the Soviet Union who staged early protests that brought her four years' internal exile; Clement N wank wo, a young Nigerian lawyer sporting an army camouflage shirt who braves government threats to handle the suits of long-term political detainees; Li Lu, a twenty-three-year-old Chinese student put on China's ''twenty-one most wanted" list after Tiananmen Square who is now attending college in New York.

One expects these witnesses to human-rights abuses to be haggard, gaunt, and grim. Of course they're not. Li Lu smiles shyly when introduced, and in Chinese style claps for the crowd when it claps for him. Others just look somewhat tired—a bit overwhelmed by this rich Western crowd—but otherwise well. Instead of anger, they emanate a perceptible calm.

It takes a minute to realize what that calm must be, so unusual is it in this Western world. It must be the calm of endurance. It must be the calm of the triumph of the human spirit over the chaos of evil. And, truly, it is inspiring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now